( – promoted by buhdydharma )

Burning the Midnight Oil for Living Energy Independence

also Agent Orange

Let construction or upgrade of a rail corridor be proposed, and almost immediately the cry goes up, “but we can’t afford it! It costs too much!”.

Let construction or upgrade of a rail corridor be proposed, and almost immediately the cry goes up, “but we can’t afford it! It costs too much!”.

Confusing the response to this cry is that there are two quite different types of “cost too much” – real, and financial.

There first “cost of rail” question is the real cost question: what is the full economic benefit, including all material and energy impacts saved versus other alternative, versus the full economic cost.

___________

Note: The first kind of “cost versus benefit” question is the kind that Ed Gleaser fumbled so badly when he assumed Zero Population Growth in east Texas, no congestion today between Houston and Dallas on the intercity road network, either deliberately or through negligence bypassed important intercity transport demands along the route of his corridor, and presumed that the only available option was the most capital-intensive type of rail corridor, the all-new, all-grade separated, Express High Speed Rail corridor.

____________

The second “cost of rail” question is the financial cost – given the complex, sometimes ad hoc, and often inconsistent sets of rules we have established for allocating resources for both investment in transport infrastructure and paying for transport operations, how do we “pay for” construction or upgrade of those rail corridors that our best analysis of cost and benefit indicate are wise investments.

That second question is what I am looking at today.

Even narrowing down to the financial “cost of rail” question, it is a very broad question.

- The balance between direct benefit and third party benefit is substantially different for local rail and intercity rail, so the share of the benefit that can support ticket receipts varies widely.

- The cost per mile varies substantially between urban, suburban and rural areas, and between available space in an existing right of way and a new alignment.

- The cost of alternative modes of transport will vary widely based on the prices that are seen in future international oil markets

- And, critically, the finance constraint faced by state and local governments is quite different to the financial constraint faced by the Federal government, which is the monopoly issuer of currency and cannot ever be forced to default on debt issues in its own currency

Since the whole problem is too big for a single post, I will be attacking the attacking this problem by starting with the Emerging/Regional High Speed Rail intercity systems. The good lord willing and the creek don’t rise, I’ll be looking to conventional intercity systems, local rail, and Express High Speed Rail over some future Sundays.

Financing Intercity Transport

A substantial share of the transport benefit of intercity transport is received by the travelers themselves – it is direct benefit. That means that if you have an intercity transport option with good benefits relative to costs in real terms, there should be substantial revenues available to that operation in the form of ticket revenue.

However, there are still a wide range of other benefits. Effective intercity transport is widely seen as an factor in promoting economic development. Freight transport in particular has often been critical in generating regional exports that have been central to regional growth.

There is also the question of property values in the vicinity of the intercity route: access to intercity transport makes a location a magnet for local transport to engage in those trips.

As a result, the US government has long provided capital subsidies of one form or another to intercity transport. The Erie and Eire & Ohio canals received substantial government support. Before the Civil War, state and local governments offered a variety of inducements to gain railroad service, and during and after the Civil War, the Federal Government was heavily involved in promoting the development of transcontinental railroads to “open up the west”, including massive land subsidies to support the capital spending required.

In the 20th century, government support for railroads was largely abandoned as attention turned to roads and air travel. Indeed, from 1942 to 1962, a rail ticket tax was in effect which, in some cases, helped to finance the construction of roads and airports.

For intercity air travel, from 1946 to 1971, Federal airport spending came out of the general fund. Since user fees were first instituted in 1971, capital spending has been made out of user fees, and when, as is normally the case, this does not leave enough to cover operating costs, a direct subsidy for operations comes out of the General Fund (cf. GAO report, page 7). The average general fund contribution is around 20% of the FAA budget, and so with operations accounting for about 60% of the FAA budget (cf. 2010 FAA budget), normally about 1/3 of FAA operations are subsidized from the general fund.

For Interstate Highways, we have a system where a Federal gas tax paid by all drivers, no matter what road they are driving on, funds a Federal Highway Trust Fund which is used to subsidize capital spending on a wide range of Interstate, US, State, Country and Township Highways, used primarily by suburban and rural motorists. So the core of capital funding for intercity road transport in the US is based on a cross-subsidy from local urban to local suburban and intercity motorists, with local city streets largely funded from property, and local income and sales taxes.

The Federal gas tax is also an excise tax without inflation indexing, so it has been falling behind explicit commitments and has recently been requiring “top-ups” from the General Fund. At the same time, as the American Society of Civil Engineers points out, the work that is performed is not keeping pace with the demands that have been placed on the roads.

The Federal gas tax is also an excise tax without inflation indexing, so it has been falling behind explicit commitments and has recently been requiring “top-ups” from the General Fund. At the same time, as the American Society of Civil Engineers points out, the work that is performed is not keeping pace with the demands that have been placed on the roads.

Of course, car operations are also widely subsidized. For example, driving requires a place to park the car, and while most parking occurs at “free” parking, “free” parking is by no means free. It is normally provided either as streetside parking out of local funds or private parking required to be constructed by zoning laws, with the cost included in rents, prices for shopping and dining, and housing prices.

Operating Finance for Emerging & Regional High Speed Rail

“Emerging” High Speed Rail is the Department of Transport lingo for 110mph maximum speed routes in existing rail Right of Way. At this speed its possible for the passenger rail services to share some track with conventional freight rail, and possible to share all infrastructure with 100mph Rapid Freight Rail.

“Regional” HSR is the lingo for 125mph maximum speed routes, primarily in existing Rights of Way. While modernized regulations would allow these services to share infrastructure with 100mph Rapid Freight Rail, they will operate on track isolated from conventional Freight trains.

These speeds are not extreme for trains – for example, the NYC No. 999 is reputed to have run over 100mph in 1893 (even if the story may be in doubt), and between WWI and WWII, trains such as the Pioneer Zephyr regularly ran faster than 100mph.

The modern technology that is to be used by the 110mph and 125 mph Emerging/Regional HSR corridors is tilt-train technology. This is not focused on hitting the fastest maximum speed, but at keeping the train near the maximum speed.

The problem is that existing rights of way are designed with curves that are too tight for trains to take at 110mph unless the track is banked – the passengers would be thrown from side to side. But if the track is banked for 110mph trains, it will be banked too steeply for 20mph and 60mph trains. So what tilt-trains do is add the extra banking required themselves, so that they can run at 110mph through a curve banked for a train to pass at 60mph.

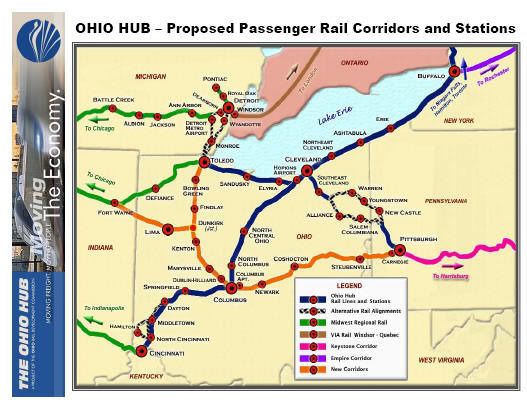

The result is a substantial improvement in effective trip speeds. For example, the line of sight distance between Columbus and Cleveland is 124 miles. Google gives the driving distance as 142 miles and the driving time as 2:15 (2 hours, 15 minutes). The proposed 110mph Ohio Hub has a sample schedule (pdf) (including scheduling leeway to permit reliable on-time service) of 1:38 for the Express running from Cleveland to Columbus, 27 minutes faster than the Google estimate driving distance and an effective line-of-sight speed of 75mph.

The result is a substantial improvement in effective trip speeds. For example, the line of sight distance between Columbus and Cleveland is 124 miles. Google gives the driving distance as 142 miles and the driving time as 2:15 (2 hours, 15 minutes). The proposed 110mph Ohio Hub has a sample schedule (pdf) (including scheduling leeway to permit reliable on-time service) of 1:38 for the Express running from Cleveland to Columbus, 27 minutes faster than the Google estimate driving distance and an effective line-of-sight speed of 75mph.

This is something of a best case example for Emerging HSR: two cities less than 2 hours apart by 110mph rail, and a 112mile (LOS) stretch between Berea and Columbus where the train can maintain an average 80mph, including stops and leeway for service reliability.

The projected operating ratio – operating revenues divided by operating costs – is 199%, reflecting the strength of the corridor for 110mph HSR.

Now, this projection refers to 2025, which means it includes assumptions of ongoing population growth, in Central Ohio in particular, and it also includes the assumption of Emerging HSR connections to Chicago available at both Cincinnati and Cleveland. And while it is based on a detailed regression model informed by existing travel, two hour and under rail trips available between Columbus and either Cleveland or Cincinnati, supplemented by one hour train trips between Dayton and either Cincinnati and Columbus is a substantial expansion of existing transport choices, so a cautious use of this projection would require including some substantial margin for error.

On the other hand, the projected operating surplus is 99% of operating costs, so even with a very substantial margin for error, the corridor would still be offering an operating surplus. And this projection is based on travel conditions circa 2005 – a rail service that acts primarily to provide a supplementary alternative to Interstate Highway traffic can be expected to provide surges in patronage during each of the oil price shocks that we can expect to experience in the decades ahead.

The take-away conclusion is that the strongest of corridors for 110mph and 125mph Emerging/Regional HSR ought to be able to cover their own operating costs, unlike road and air transport … and yield a surplus. And that potential for operating surplus is key to the specific question of how to finance these rail corridors.

Capital Finance for Emerging & Regional High Speed Rail

Substantial capital subsidies and cross-subsidies since the end of World War II account for the intercity transport system we have today, with its heavy emphasis road and air transport. I have seen an estimate that the airport and air traffic control infrastructure we built up before starting to charge users for a portion of the costs amounted to over $1 Trillion in 1980 dollars.

And the Federal Government is proposing to subsidize Capital spending on High Speed Rail systems, with an original $1b annual request by the White House expanded to $1.2b in the Senate and $4b in the House. Indeed, Transport for America among others are, as I write, engaged in an advocacy campaign to push for adopting of the $4b House figure in conference.

While $4b itself may seem relatively small set against the $41b the Department of Transport budgeted for highways, Emerging and Regional HSR is quite capital efficient.

For example, the Cleveland to Cincinnati section of the Ohio Hub is projected to cost $1.104b in 2002 dollars, or about $1.4b in current dollars. Adding in a +/- 30% margin of error for feasibility study precision of estimation, and the cost is comfortably under $2b, for capital works on 260miles of corridor with a life of 30 years and up. That is a capital cost of under $8m/mile (possibly under $6m/mile), similar to project portion of the capital cost of adding a lane each way to an Interstate Highway.

But of course, Ohio is just one state, and the Triple-C is just the strongest segment of one longer corridor in a system of three long corridors and a cross-connector, connecting to additional planned corridors to its east and west.

And should the infrastructure be entirely Federally funded? States pay 10% of the costs of constructing new Federal Highways, and even in the days before User-fees starting contributing to FAA capital spending, local tax-exempt bonds provided some of the finance for our nationwide system of airports.

Of course, the state matching portion of Federally funded infrastructure projects are not in place because the Federal government cannot “afford” to invest in a project. If an infrastructure project is economically justified in terms of providing more economic benefits than costs, and if the country can afford the impact on the external accounts, the Federal government can always “afford” 100% funding of these projects.

The purpose of state matching funds is to act as a check on states requesting investment in projects simply for the short-term benefit to economic activity due to the project, even though there is no substantial need to be met by the project. And based on the evidence of how states act with respect to highway funds, it would seem that a 90% Federal, 10% State match is not an adequate check.

So I will suppose that the Federal formula for capital grants to intercity Emerging and Regional HSR is 80% Federal, 20% State. This means that the $1.4b-$1.8b for the Ohio Hub would be a Federal Share of about $1.1b to $1.5b – or, in other words, the proposed Senate funding for HSR would fund the equivalent of one “Triple-C” Cleveland to Cincinnati line, including stations and trains, every year to year and a half. The $4b proposed by the House would fund the equivalent to two and a half to three and a half.

Or, in other words, maintained over five years, and assuming its adjusted for inflation, the Senate proposal would fund four to five corridors equivalent to the Triple-C corridor, while the House proposal would fund 13 to 17.

Now, the HSR funding is not restricted to Emerging and Regional HSR, but it seems clear that at least the House funding levels are adequate for providing an 80% Federal share of the capital costs of a substantial assortment of Emerging and Regional HSR corridors.

But, no matter what the theory of the state match may be, the question must be asked, where are states to find the matching funds? One possible answer looks back to the issue of operating funds.

Foundation Corridors as Seeds of Growth

Suppose that the 110mph version of the Triple C was established, and the patronage it attracted put it on track to meet the projected 199% operating ration. What kind of money are we talking about here? Well, from the same Financial Viability study, that is revenues of $100m against operating costs of $50m.

Now, assume a cautious real discount rate of 5%, 20 years of revenue bonds funded by a revenue stream of $10m is about $150m, which in a 20:80 match can help fund a project of about $760m. So for a corridor with operating costs of $50m, operating ratios above 100% translate into potential funding for system expansion:

- 120% ==> $10m/yr ==> $760m

- 150% ==> $25m/yr ==> $1.9b

- 200% ==> $50m/yr ==> $3.8b

In other words, once an effective keystone corridor has been established, it can yield a revenue stream that can provide the state matching funds for ongoing expansion of the system.

What about the objection that, if the state provides its matching funds using revenue bonds funded from operating surpluses, the check on “reckless expansion” has been lost? The reality is that if states pursue this approach, the check is even more effective.

The reason is straightforward. Any ambitious “empire builder” operating under this approach must continue building corridors that can grow the patronage to deliver operating surpluses. At the point that a corridor is built that is unable to build the patronage for an operating surplus, it reduces the revenue bonding capacity of the system as a whole, and so slows the growth of the system as a whole.

Rail Electrification

An important area where the potential for an operating ratio over 100% is very useful is rail electrification. Electrification will reduce operating costs of an operation and, because of the greater traction available when electric motors are distributed along the length of the train, increase acceleration and deceleration, further reducing trip speeds. Indeed, in a 110mph corridor, electrification may be one of the improvements supporting upgrade to 125mph operation.

An important area where the potential for an operating ratio over 100% is very useful is rail electrification. Electrification will reduce operating costs of an operation and, because of the greater traction available when electric motors are distributed along the length of the train, increase acceleration and deceleration, further reducing trip speeds. Indeed, in a 110mph corridor, electrification may be one of the improvements supporting upgrade to 125mph operation.

Further, electrification allows the Emerging/Regional HSR network to be more easily powered by sustainable, renewable power sources, since direct electric power sources such as wind turbines offer far more energy capacity and higher rates of Net Energy Return on Investment than biofuels such as biodiesel.

However, while electrification improves operating costs, it is capital intensive, and when capital costs are limiting the speed of roll-out of the system, there would seem to be a risk of delaying electrification until after a regional system is entirely built out.

However, if the capital expenditure is provided for separately, there is no need to wait. Provided that finance is made available, it is possible to build the electric infrastructure and charge the rail operator a user fee for the use of the electricity – with the user fee refunding the capital costs.

Indeed, as proposed last week, it is possible to accelerate electrification even faster. The proposal is to allow states to use a portion of the state share of Carbon Fees to provide an interest subsidy on the infrastructure to support Rapid Electric Freight Rail.

Under this proposal, electrification of Emerging/Regional HSR can be integrated into electrification of a longer Interstate Freight Corridor along the STRACNET system, allowing the earlier roll-out of electric trains along that segment of the system, with diesel trains freed up in the process free to be used in more recently established corridors.

Overview

So, this is the general framework. First, establishing a sufficient Federal HSR funding stream to support the establishment of “multiple Triple-C corridor equivalents” each year. Second, going to states for bond funding for the establishment of the strongest Emerging HSR corridors in the various systems under development. Third, building up patronage in the keystone corridors to the point of financing revenue bonds for system expansion. And fourth, establishing a separate system with its own stream of Carbon Fee funding for Rapid Freight Rail electrification which can also be leveraged to the benefit of Emerging and Regional HSR corridors.

Of course, the reason that I started with Emerging/Regional HSR corridors is that it is, in a certain sense, the easiest place to start.

Heading off in one direction, once we reach the point of conventional rail corridors, where such a dominant share of the benefit is external benefit, we need to work what conditions will generate an operating surplus and, under those that do not, how we can sustainably finance an operating deficits.

Heading off in the other direction, while well-chosen Express HSR corridors can certainly generate operating surpluses, they are also dramatically more capital intensive than Emerging/Express HSR corridors, and that generates its own set of problems.

So while this is a pause point – in reality, its just the tip of the iceberg.

1 comment

Author

… cause despite the regular freights and the tracks going every which way, there ain’t been no passenger train in this here town for decades.