(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

Crossposted at Daily Kos

|

The story continues below the fold…

Poets, Artists, Authors, and Soldiers in the Spanish Civil War

If you are a romantic by nature rather than a cynical, hardcore realist, you will come away impressed by the art and literature that emanated from this brutal conflict. In May 1937, George Orwell was hit by a sniper’s bullet in the throat. About the same time, P.O.U.M. was outlawed by the Stalinists and its members hunted down. A few weeks later, Orwell and his wife escaped from Catalonia and returned to England. Homage to Catalonia was the result of his experiences in Spain.

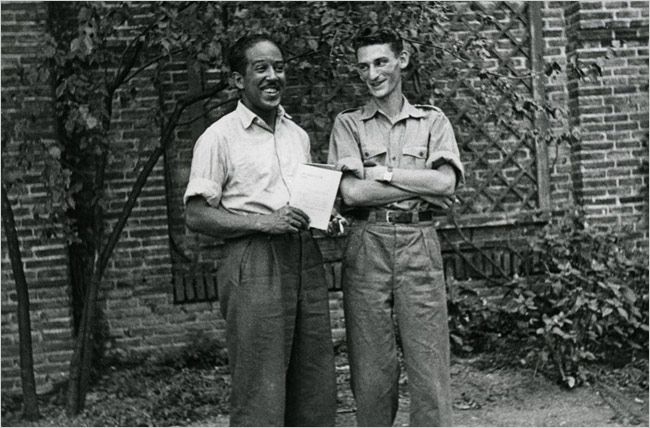

Along with the men and women of the international brigades, many intellectuals, photographers, artists, and foreign journalists flocked to Republican Spain to capture the sights and feel the pulse of this war. Along with many others, George Orwell, Paul Robeson, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Capa, Langston Hughes, Andre Malraux, Kim Philby, Willy Brandt, Emma Goldman, and John Dos Passos joined the cause. They wrote extensive stories that informed the rest of the world, offered words of encouragement, and organized help for the beleaguered Republicans. Some risked their lives to accompany troops in battle and took photographs and notes that made them as famous as the conflict itself. In fact, the Spanish Civil War produced some of the more memorable images and words ever written about any war in history.

Ernest Hemingway struggling to use his gun during the Battle of Teruel in Aragon, Photo Source: “Robert Hale Merriman: A Tribute to an Early-Antifascist”.

|

ALB volunteer Robert Merriman arrived in Barcelona from California in January 1937, where he had been an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Having received two years of ROTC training at the University of Nevada, he was soon slated to command one of the volunteer battalions and would take part in several major battles over the next year.

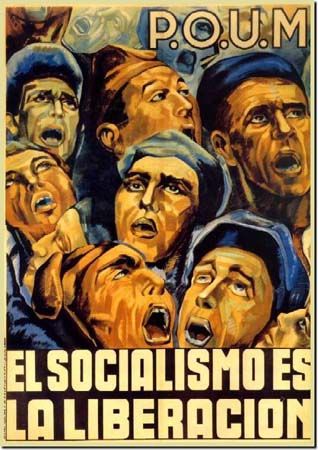

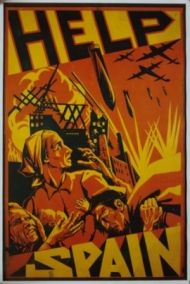

Upon his arrival in Spain, Merriman saw the city “aflame with posters of all parties for all causes”

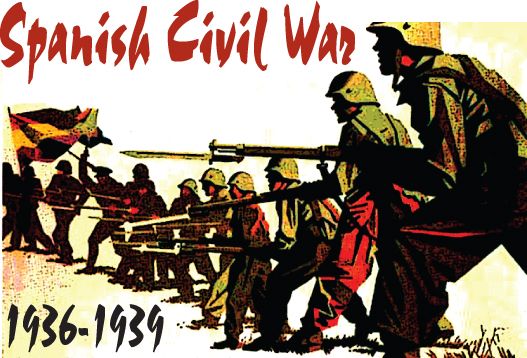

Full-color posters, banners, and fliers, brandishing dramatic swaths of red and black or blue or yellow were all over the city: along the streets, taped to windows, tacked up on kiosks in every public square, on the interior walls of office buildings and private homes, in all the subway stations, on the sides of buses, trucks, and even trains…

They were first of all an excellent mode of communication for a population with a high rate of illiteracy. For many years, Spain’s Catholic church, in control of public education, believed there was no need for either peasants or women to read. The Republic would begin rapidly to reverse that pattern, but in the meantime posters in public places combining striking iconography with brief slogans made it possible to get basic messages out to people quickly. The combination of strong graphics with concise captions also made the posters memorable and convincing.

“The Spanish Civil War Poster ” – Source: ALBA – The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, Photograph Source: “Robert Hale Merriman: A Tribute to an Early-Antifascist”. Merriman is the tall, bespectacled soldier in the middle. He was killed in action near the city of Gandesa in April 1938. To read an excellent article about the history of almost 100 posters and learn more about the artists, see this article “Images of Revolution and War” – Source: The Visual Front, the University of California San Diego Southworth Collection.

As I wrote in my diary earlier this year about activist, actor, and singer Paul Robeson (if you’ve read my diary, he was much, much more than that simple description), he was attracted to Spain for a variety of reasons

He was one of the top performers of his time, earning more money than many white entertainers. His concert career spanned the globe: Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Moscow, New York, and Nairobi.

Robeson’s travels opened his awareness to the universality of human suffering and oppression. He began to use his rich bass voice to speak out for independence, freedom, and equality for all people. He believed that artists should use their talents and exposure to aid causes around the world. “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice,” he said.

This philosophy drove Robeson to Spain during the civil war, to Africa to promote self-determination, to India to aid in the independence movement, to London to fight for labor rights, and to the Soviet Union to promote anti-fascism. It was in the Soviet Union where he felt that people were treated equally. He could eat in any restaurant and walk through the front doors of hotels, but in his own country he faced discrimination and racism everywhere he went.

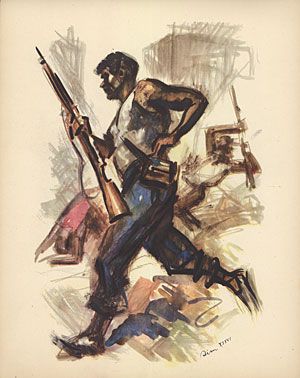

Paul Robeson and his wife Eslanda Goode, Sketch Source: ALBA – The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives.

|

Artistic creativity is a totalitarian regime’s worst nightmare unless the artist narrowly conforms to the regime’s twisted ideology and toes the party line. Given their anti-intellectual bent, totalitarians are perpetually fearful that words and images can act as powerful symbols and sometimes convey hidden messages that can appeal to and galvanize their opposition. For these regimes, tolerating dissent is for the weak-minded and must not only be stifled but crushed.

In this diary that I wrote a few years ago (it is about artistic freedom and independence – Aristotle, Shakespeare, and Dickens Set Free in China), I described how through the brilliance of his words French philosopher and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre tricked his Nazi occupiers at the time

Jean-Paul Sartre wrote Les Mouches (or as translated in English, The Flies) in 1944. The play was essentially an 20th century adaptation of Sophocles’ Greek mythological tale of Electra and was first enacted before a sold-out crowd in a fancy Paris theater during the Nazi occupation of France. Seated in the front row were leading members of the German Army brass along with several SS officers. Just as the dominant theme in Electra was revenge and restoring the family’s honor, Sartre was imploring his countrymen to resist the Nazi occupation. The play was a brilliant, subtle call-to-arms to his countrymen to re-evaluate their collaborationist tendencies and resist the German occupiers

Orestes: Electra, behind that door is the outside world. A world of dawn. Out there the sun is rising, lighting up the roads. Soon we shall leave this place, we shall walk those sunlit roads, and these hags of darkness will lose their power. The sunbeams will cut through them like swords.

Electra: The sun…

First Fury: You will never see the sun again, Electra. We shall mass between you and the sun like a swarm of locusts; you will carry darkness round your head wherever you go.

Electra: Oh, let me be! Stop torturing me!

Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit and Three Other Plays, p 111.

Sartre later wrote that while almost all of the French attendees in the audience understood the underlying message of his play, it completely eluded the Germans.

“The Falling Soldier” has long been considered one of the most famous war photographs ever. Taken by photographer Robert Capa, it first appeared in LIFE magazine on July 12, 1937. It shows a Republican soldier falling to his death in Cordoba just as the bullet is passing through his head. Over the past few decades, controversy has surrounded the photo’s authenticity and recent revelations point to the fact that, indeed, it may have been staged for the photographer.

Gerda Taro was Capa’s fiance at the time and is believed to be the first female war photographer to have been killed in action. She was brilliant at what she did. It was reported at the time that she had been been “accidentally” killed in 1937 when trampled upon by a Republican tank in a large-scale Republican retreat during the Battle of Brunete near Madrid. In 2008, an article in the New Statesman suggested that she may have been murdered by Stalinists

|

Poet Federico Garcia Lorca must have also posed an existential threat to General Franco. He was one of the first victims to be executed by Franco’s firing squads in August 1936. He was thirty eight years old

Federico Garcia Lorca is possibly the most important Spanish poet and dramatist of the twentieth century.

In 1936, Garcia Lorca was staying at Callejones de Garcia, his country home, at the outbreak of the Civil War. He was arrested by Franquist soldiers, and on the 17th or 18th of August, after a few days in jail, soldiers took Garcia Lorca to “visit” his brother-in-law, Manuel Fernandez Montesinos, the Socialist ex-mayor of Granada whom the soldiers had murdered and dragged through the streets. When they arrived at the cemetery, the soldiers forced Garcia Lorca from the car. They struck him with the butts of their rifles and riddled his body with bullets. His books were burned in Granada’s Plaza del Carmen and were soon banned from Franco’s Spain. To this day, no one knows where the body of Federico García Lorca rests.

“Federico Garcia Lorca” – Source: Poets.org, Sketch Source: A Writer’s Desk. This very recent article in the Guardian suggests that Lorca’s killers had probably never read his poetry and had the mindset of Fascist “careerists” that I alluded to in this diary of mine – Hannah Arendt, Imperialism, and Neoconservative Careerists.

Edwin Rolfe came to known as the poet laureate of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. His poem “Elegy for Our Dead” was first published in January 1938 in the English language magazine of the international brigade, Volunteer for Liberty (Nelson, p. 76). Rather than the isolationism that gripped his country at the time, it celebrates the international aspect of this fight against Fascism.

In 1947, Rolfe was blacklisted and investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and wrote a series of anti-McCarthyite poems until his death in 1954. His poems and many others can be found in The Wound and the Dream: Sixty Years of American Poems about the Spanish Civil War.

“Elegy for Our Dead”

Honor for them in this lies: that theirs is no special

strange plot of alien earth. Men of all lands here

lie side by side, at peace now after the crucial

torture of combat, bullet and bayonet gone, fear

conquered forever. Yes, knowing it well, they were willing

despite it to clothe their vision with flesh. And their rewards,

not sought for self, live in new faces, smiling,

remembering what they did here. Deeds were their last words.

To learn more about Edwin Rolfe’s life, see these articles by Cary Nelson – “Edwin Rolfe: Biography” and “A Review of Rolfe’s Collected Poems”. Also read this Wikipedia article about the “Hollywood Blacklist.” In addition to Rolfe, it includes details about many important figures in the entertainment industry who were blacklisted during the McCarthy era for their political beliefs. The photograph shows six French members of the international brigades in Madrid, 1936. Photograph Source: Spartacus Education, U.K.

Internal and External Developments That Determined the War’s Outcome

The civil conflict in Spain was the prelude to and trial run leading up to World War II. Many internal and external factors determined the outcome in Spain.

On this blog, we often discuss the Democratic Party’s endless capacity to form figurative circular firing squads and eat its own. In Spain, there were real circular firing squads amongst the various Republicans factions. It can be best described as a “war within the war” and one which was heavily publicized in newspapers, colorful posters, pamphlets, and books. If you have read George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia (1938), you would recall that he described the leftist groups fighting for the Republican Government as poorly organized, with multiple and conflicting goals, frequently short of arms and ammunition, and often at political odds with each other. At times, the consequences of this infighting between the Communists and Anarchists (and their allies) were fatal and resulted in many deaths in May 1937 in the Catalonian city of Barcelona. This deadly clash occurred primarily due to decades of underlying ideological hostility towards each other.

At the heart of these internecine rivalries was the ultimate goal of the struggle against General Franco’s reactionary conservative forces. Assisted by Joseph Stalin’s NKVD agents (later, the KGB), the Communist Party of Spain promoted and ruthlessly enforced its aim of “First the war, then the revolution” through repression. Orwell wrote in glowing terms about the egalitarian conditions created by workers in Catalonia while despising the heavy-handed, thuggish tactics of the Communists. (Orwell, p. 2) Counterintuitive as it may seem, it was the Communists (PCE and PSUC) who were anti-revolutionary in this fight. Considering the war and revolution to be inseparable, the Anarchists (CNT) and Socialist parties (POUM and PSOE) had other ideas and cherished this revolution from below, particularly in Catalonia.

(in this BBC video, you will see what George Orwell actually observed in Catalonia and later wrote about in his book. I think it is an actor playing him but you do get a still shot of a tall man, who is the real Orwell. Familiarize yourself with all the numerous Republican political parties in this conflict. Many of the differences between them may, at first glance, appear to be minor but were, in fact, irreconcilable.)

When Orwell arrived in Spain in 1936, he joined the P.O.U.M. (Partido Obrero de Unificacion Marxista) or the Worker’s Party of Marxist Unification. Formed in 1935, it was decidedly anti-Stalinist and largely consisted of former Trotskyites. Based on his experiences, he explained these internal divisions brilliantly in his book and why the “Right” (Communists and their allies) stifled the revolution

|

In spite of this ever-present tension and struggle for achieving primacy — and even if there had existed perfect political harmony amongst the competing leftist factions — Orwell lays the blame for his side’s defeat squarely at the feet of the Western powers, whose policies were disjointed, inadequate, and, even, duplicitous in preventing the Fascists from winning in Spain. (George Orwell, “Looking Back On The Spanish War” – 1943)

Notwithstanding the few thousand volunteers of the international brigades, the United States and most other European countries were not only suffering the debilitating effects of economic depression but were also in political isolationist mode. Fearful of a wider European war and with memories of the devastation caused by World War I still fresh on their collective minds, 27 countries signed a Non-Intervention Agreement in September 1936, vowing not to arm either side in Spain.

Signing international agreements is one thing; abiding by them something altogether different. Once Germany and Italy started sending arms and troops in violation of the agreement, so did the Soviet Union. Other countries either maintained their stance of neutrality or sent minimal aid. Britain’s Tory government, first under Stanley Baldwin and, then, Neville Chamberlain refused to get involved and ignored the massive support amongst British intellectuals and the working classes for the Republican cause in Spain. Instead, many of their cabinet officials as well as business elites were sympathetic to Franco’s Nationalists. In the case of French Prime Minister Leon Blum, who had been elected in February 1936 as leader of the Popular Front and should have been an ideological soulmate to Spain’s Second Republic, intense external and internal pressures were exerted upon him not to send aid in this “factional” conflict. It is interesting to note that the American embargo on Spain did not prevent Texaco from providing 3.5 million barrels of oil to General Franco’s Nationalists throughout the civil war. Texaco was not the only American corporation to engage in such predictable behavior.

(British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, above, in London upon his return from Munich in 1938 after meeting with Adolf Hitler and reaffirming Britain’s desire never to go to war with Germany again, Source: The Observer, U.K.)

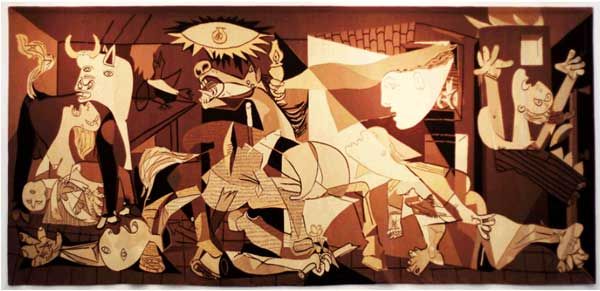

The Munich Pact of September 1938 signaled the western powers’ unwillingness or inability to confront Fascism and fight for their beliefs. In World War II, they would rectify this horrendous mistake. Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, perhaps more concerned with building “Socialism in One Country,” was militarily unprepared for a major war. However, in exchange for Spain’s gold reserves, it did send significant military aid to Republican forces but, importantly, very few fighting troops. Later, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 — which sealed Poland’s fate and plunged the world into a global war — was signed largely as an acknowledgement of the USSR’s limited military capabilities. General Franco’s Nationalist forces were actively aided with the latest in military technology and troops by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. An important aspect of this was that the Nationalists were able to achieve air superiority by 1937, one that gave them a clear advantage.

The Western democracies could have done a lot more to aid the Spanish government but for a variety of reasons chose not to do so. German and Italian military aid would prove to be crucial in helping the Nationalists ultimately prevail over the Republicans.

Given that the odds were heavily stacked against his side, Bill Bailey later wrote in his memoirs that after a particularly difficult day on the battlefield, he had no regrets or feelings of remorse about fighting in Spain for a cause he deeply believed in and may have subconsciously been preparing for his entire life

I even try to find humor in the situation by asking myself what the hell I’m doing here, going through all this torture, when I could be safely home with an easy task like passing out leaflets calling for support of the Spanish people’s cause or stuffing envelopes for some political campaign. I’d be free from the dangers and the stink of death all around me. I know I would not be satisfied with that, and I try to remember where it all started, this great urge to right the wrongs of an insane society. Was it back when that cop slugged me on the picket line during my first effort to build a union? Or was it during the reform school riot when the guards forced me up against the wall with my hands raised over my head and made me watch as they clubbed into unconsciousness many of my friends?

No, it went back farther than that. Somewhere the handwriting was on the wall and my destiny was spelled out for me. Perhaps it was when I was clutching fast the handle of the baby carriage… away back to those tiny hands clutching the handles.

Bill Bailey, The Kid from Hoboken, Prologue – 1993. After Catalonia was overrun by the Nationalists in February 1939, only Madrid and surrounding areas remained in Republican hands. By late March, the capital fell and the war was finally over on April 1, 1939, Source: Boston College.

Back Home From Over There: “Premature Anti-Fascists”

By the end of 1938, most members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade would return from Spain. In a last-ditch effort to change the course of the war, the Republican government would withdraw the international brigades, expecting that Germany and Italy would also do the same and recall all of their troops from Spain. Both countries refused to do so. The war would be over in a few more weeks.

|

Bill Bailey, Milt Wolff, and the other ALB volunteers had no idea what awaited them back home upon their return from Spain and how their lives would unfold. They did not necessarily make peace with the system they had defied in 1936. In coming decades, they agitated and protested on behalf of a number of progressive causes.

The Lincoln Brigade veterans, like most other Americans, looked forward to the postwar world with considerable optimism. By 1945, their fight against fascism that had begun nearly ten years before appeared to be won, a fact that eased some of the disappointment they had carried leaving Spain in defeat. On the domestic front, many Lincolns hoped that the progressive movement that had made such great progress in the 1930s would be able to build upon the successes of the New Deal, strengthen the industrial union movement, and perhaps set the stage for socialist reform… By the early 1950s most of the Lincolns were facing the political inquisition. The campaign culminated in a Subversive Activity Control Board hearing in May 1954. Although several veterans testified that they went to Spain to fight fascism, not to support communism, the government relied on FBI informers and veterans who were disillusioned with the Communist party to establish a direct link between the Lincoln Brigade and the party.

The Lincolns, like so many other radical organizations, were decimated by the Red Scare and blacklists of the late 1940s and 1950s. But when the long night of the fifties began to lift and the civil rights and antiwar movements began to gather strength, the veterans were still around. During the next quarter-century and beyond, they once again took up the banner of the good fight as part of the peace movements that opposed U.S. wars in Vietnam, Central America, and the Middle East.

“Premature Antifascists and the Post-war World” – Source: ALBA.

In 1997, British writer Tony Hendra traveled to Spain for a reunion of members of all the international brigades who had fought in Spain.

He wrote an excellent article in Harpers Weekly magazine recounting what had happened to these men and women over the previous five decades

The images of young men that were everywhere in Madrid early last November — erected in respectful displays, handed out with somber programs — bore that inimitable look ordinary young men had in the 1930s: the stark, black-and-white boniness against backgrounds of flat sunlight. Young, hopeful, often happy figures, never on tanks or armored vehicles or with any kind of advanced weaponry — one sees that clearly now — always on foot, clutching ancient rifles, in the dirt outside a dusty pueblo or against a shell-pocked wall, soccer-team style, one row standing, one row kneeling, as if the game were already won, victory theirs; they and what they fought for, seen in simple black-and-white…

They found out soon enough that there was nothing simple about the Spanish Civil War — not in their retreat, not in their defeat not in their homecoming. For the rest of their lives, the mad, Byronic, utterly decent decision they made to die, if necessary, to stop fascism would be held against them. They were hounded into prisons and concentration camps, blacklisted, ostracized, driven to poverty, suicide, and oblivion — often in the name of the very principles they’d tried to defend. The only ones for whom things turned out to be simple are still lying beneath the tawny dust of Spain.

“In Spain, the International Brigades Join Ranks One Last Time” – Source: Harper’s Weekly. Read more about this ridiculous concept in this excellent article by Bernard Knox, “Premature Anti-Fascist.”

Over a third of the ALB volunteers were killed in Spain. No one forcibly drafted them. They weren’t coerced in any way. No pressures were put on them to risk their lives for another country. Many had never fired a gun let alone receive any formal military training. They were certainly not motivated by profits or other commercial concerns but, rather, simply cared a great deal about their fellow human beings. These brave, and largely-forgotten, men and women traveled to a land most had never seen before nor had any familiarity with. They went to Spain because they believed deeply in their cause.

Those who were lucky enough to survive and return home were labelled “Premature Anti-Fascists” by their government. Doesn’t that oxymoronic term imply that the ALB volunteers were prescient in their contempt for Fascism? No matter the period and the circumstances, I don’t think it is ever inappropriate to oppose a deadly and discredited Rightist ideology like Fascism. What in the world was our government thinking? (Flag Source: Legends of Our Time)

In 1939, Ernest Hemingway wrote of their colleagues who didn’t make it back home

The fascists may spread over the land, blasting their way with weight of metal brought from other countries. They may advance aided by traitors and by cowards. They may destroy cities and villages and try to hold the people in slavery. But you cannot hold any people in slavery.

The Spanish people will rise again as they have always risen before against tyranny. The dead do not need to rise. They are a part of the earth now and the earth can never be conquered. For the earth endureth forever. It will outlive all systems of tyranny.

Those who have entered it honorably, and no men ever entered earth more honorably than those who died in Spain, already have achieved immortality.

Photograph Source: Fred Klonsky’s Blog. Author John Dos Passos is on the far left, with Hemingway reading notes in Madrid, Spain.

Bill Bailey passed away in 1995. He was eighty five years old. He never did have to mail that letter he had written to his mom from Spain in 1937.

|

Losing the Battle, Winning the Eventual War

It is often said that the victors of a war, any war, write its history. This is mostly true with perhaps one major exception. Over the years, World War II came to be known as the “Good War” (if there is such a thing) for much of the Western world. In the decades since it ended in 1939, the Spanish Civil War has been regarded by many historians as a war fought for a worthy and just cause, even though it was lost by those supporting democratic reform and change. Its history was not defined and written by the winners.

General Franco would rule Spain with an iron hand for almost four more decades until his death in 1975 spelled the beginning of the end for Fascism. For Spaniards, political killings, executions, and imprisonment numbering in the tens of thousands would become a thing of the past. Many memories of Franco’s autocratic reign would be expunged from Spanish history as if it were a bad dream. Over the next decade, a new Spain would gradually emerge from the dark shadows of authoritarianism, make the transition to parliamentary democracy, and, eventually, join the European Community in 1986. Sooner or later, every nation must confront its ghosts. After decades of silence, so did democratic Spain. In many respects, the Spanish Civil War would finally be over. The forces of light would largely triumph over the forces of darkness.

Thanks to millions of Spaniards who made unimaginable sacrifices and fought the “good fight” against Fascism — with a small assist from people like Bill Bailey and other volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade — Generalissimo Francisco Franco would not have the last word on the future direction of Spain.

Towards the end of the last episode of The Good Fight, there is a touching scene that shows some level of recognition for the remaining veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. (ALB – go to about the 6:00 mark of the video) The background music in the video is the stirring Spanish Republican song “Viva la Quince Brigada.” The music is uplifting as the tune goes back to Napoleonic times.

In 1981, a crowd including Bill Bailey and a few other ALB veterans are participating in a “March on Washington” and protesting Ronald Reagan’s military policies in support of the authoritarian regime in El Salvador. The protest is taking place in front of the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. The ALB veterans are wearing their trademark berets and are walking slowly due to their advancing years but proudly displaying the ALB banner. Many protesters, including a younger veteran in uniform, are clapping, cheering them on, and expressing gratitude by shaking their hands as appreciation for their sacrifices.

At that point, seemingly out of nowhere, a young protester in his twenties rushes up to Bailey to shake his hand. The look on the young man’s his face is one of awe and admiration for the old veteran

Young Protester: Thank you. Thank you very, very much.

Bill Bailey: You’re welcome. Thanks for coming down here.

Young Protester: We have the same heart. I hope my generation has the same courage as yours.

Bill Bailey: Don’t worry. You’ll get it.

A Note About the Diary Poll

One of the best-known movies about this conflict was based on Ernest Hemingway’s personal experiences as a foreign correspondent in his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Released in 1943, it is the story of a a young American idealist Robert Jordan (played by Gary Cooper) who, not unlike Bill Bailey, travels to Spain to fight for the Republican cause.

Hemingway borrowed the movie’s title from English poet, author, and priest John Donne’s religious reflections Meditation XVII of Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, written in 1624

|

There’s some debate about what precisely was meant; some view it simply that Donne was pointing out people’s mortality and that when a funeral bell was heard it was a reminder that we are nearer death each day, i.e. the bell is tolling for us…

Ernest Hemingway helped to make the phrase commonplace in the language when he chose to use the quotation for the title of his 1940-published book about the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway refers back to “for whom the bells tolls” and to “no man is an island” to demonstrate and to examine his feelings of solidarity with the allied groups fighting the fascists. There was a strong feeling amongst many intellectuals around the world at the time that it was a moral duty to fight fascism, which they feared may take root world-wide if not checked.

This was given voice later in the well-known poem First They Came… and one attributed to Pastor Martin Niemoller.

No matter the country, economic despondency is the crucible in which radical ideologies are formed and either flourish or veer dangerously off course. Many of the “isms” of the day in the early 20th century — Marxism, Communism, Socialism, Anarchism, Fascism, Imperialism, Monarchism, Liberalism, Capitalism, Nationalism, and Conservatism — were in a state of flux and their future relevance unknown to many. Still, people held deep beliefs in the hope that their ideological commitments would provide a road map to economic and social salvation. In this age of ideology, rapid industrialization and the rise of the working classes would clash with traditional societal structures and often result in conflict.

It is in this context and through this lens that one should view the different factions who fought in the Spanish Civil War and the contributions of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In coming decades, a few of these political and economic systems would be confined to the dustbin of history and the world transformed as a result. In some way, shape, or hybrid form — and for better or for worse — others still survive to this day. (for discussion on some of these concepts, see this diary that I wrote only a few weeks ago, George Orwell and Howard Zinn on Patriotism and Nationalism)

If one of your family members or their acquaintances were involved in any way in this effort in the 1930’s, I would be particularly interested in hearing about it in the comments section. If you are unsure, you can enter their names and search the online data base of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA) based in New York University’s Tamiment Library.

Don’t forget to take the diary poll.

2 comments

Author

When Franco’s Nationalists revolted on July 18, 1936 and Madrid was under siege by the rebels, Dolores Ibarruri Gomez, a member of the Partido Comunista de Espana (or, the Communist Party of Spain), gave a speech using these two words. The words were first used by French General Robert Nivelle during the Battle of Verdun (French: “Ils ne passeront pas/On ne passe pas”) between the German and French armies in World War I. That bloody battle in Northeastern France resulted in 306,000 deaths.

“!No Pasaran!” would become a political slogan and symbol of Republican defiance and determination. Banners were seen all over city streets expressing this strong desire to confront the rebels. The siege would last for almost three years until Madrid fell to Franco’s forces in late March 1939. Ibarruri — famously known as “La Pasionaria” or, passion flower — lived abroad in exile for 38 years and returned to Madrid in 1977, winning a parliamentary seat later that year in the Spanish Parliament at the age of 81. She was also the honorary president of the Communist Party of Spain until her death at age 93 in 1989.

(Poster Source: The Great War)

In reading this two-part diary, you will undoubtedly recognize political themes and arguments still relevant to and resonating even today in our politics. Politicians come and go but some issues and concerns never seem to change. As long as this diary is, this is by no means an in-depth study of the Spanish Civil War, a huge and complicated subject. I have made many references to and summarized major events, roles played by major players, and ideological movements (each of which probably merits several diaries) in the United States, Spain, and on the international level. In doing so, my objective was to provide some background historical information and context. You are welcome to comment on anything but I hope you will keep in mind that the primary focus of this diary is to highlight the efforts of a few of the 2,800 Abraham Lincoln Brigade volunteers who fought in Spain.

Today, I wonder how many of us would be willing to make similar commitments like the Abraham Lincoln Brigade volunteers did in the 1930’s. A few amongst you might disagree with their radical political beliefs and, perhaps, even the methods they used to pressure their government. Even so, one can’t but think of them as a highly principled group of Americans who made great sacrifices.

May all of us have the courage to act upon our political beliefs. Comments strongly encouraged. Tips and the like here. Thanks.

ps: there are almost 150 links in this diary along with 40-50 images and videos. If a particular link interests you — and your old computer’s RAM is low — simply right click the link and, then, click ‘Open Link in New Tab.’ That way you wouldn’t have to either move away from the diary page or reload this long diary.