Greetings, literature-loving Dharmists! (do we have a group name yet?) This is a crosspost of my dailykos series, profiling famous and not-so-famous names in literary history. Last week we spent time in West Africa with the former president of Senegal, who also happened to be a cultural theorist and excellent poet. Our subject this week was also involved with politics, although on a much more modest scale: he was friend and informal adviser to Czechoslovakia’s first elected president, Tomáš Masaryk.

Since the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina two years ago this week, one of this author’s novels has become uncomfortable to read, because he had once imagined in agonizing detail the destruction of the Gulf Coast due to humanity’s meddling with nature. Join me below for an extended discussion with a true visionary, and one of the foremost liberal humanists of the 20th century.

It is time to read Capek again for his insouciant laughter, and the anguish of human blindness that lies beneath it.

This said, the most important thing about this writer remains to be noted – his art. He is a joy to read – a wonderfully surprising storyteller of some fairly astonishing and unforgettable tales.– Arthur Miller

Though I’m likely to cover a host of lesser-known writers in this series, the relative obscurity of Karel Capek confuses me most. It’s certainly not for lack of trying, since his résumé is intimidating: novelist, playwright, photographer, philosopher, humorist, journalist, children’s author, gardening expert, artist, etc. But here we stand decades later, and Capek’s fame lies mostly in a footnote to a single word, and an inaccurate footnote at that.

Biography:

Karel Capek was born in what is now the Czech Republic, but what belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire when he was born in 1890. In a period of less than a decade, the Czech lands saw the birth of three titans of early 20th century literature: the raucous Slavic Cervantes Karel Hašek, the moody Jewish-German genius Franz Kafka, and the relentless innovator Karel Capek.

Karel Capek was born in what is now the Czech Republic, but what belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire when he was born in 1890. In a period of less than a decade, the Czech lands saw the birth of three titans of early 20th century literature: the raucous Slavic Cervantes Karel Hašek, the moody Jewish-German genius Franz Kafka, and the relentless innovator Karel Capek.

By the time the Czech lands achieved their independence, the Czech language and identity were still struggling to define themselves after having been nearly obliterated during centuries of foreign rule and forced use of German. Some groundwork had been laid in the 19th century by good (but not great) poets like Erben, Nemcová and Neruda, but Capek’s virtuoso skill with the language and his expansion of that skill into such disparate genres as newspaper editorial, science fiction fantasy, and technical handbooks made possible later Czech writers like Kundera, Škvorecký, Hrabal, Klíma, and Havel.

The bulk of his creative output took place between the World Wars, and Capek recognized that one of the most destructive forces at work in interwar Europe was the belief that all humanity could be brought under a single political framework “for the greater good”. Like Dostoevsky, he had an instinctive fear of Universal Solutions, recognizing the seeds of authoritarianism whether in fascism, communism, religion, or even science (remember that this was the age of eugenics). Capek transformed these fears into fantasy landscapes of the human race’s worst qualities run amok, where dreams of perfection inevitably turn destructive.

But unlike many writers of dystopian fiction, Capek is never bitter or misanthropic – his love for the human race leaps off the page in warm caricatures. He was a cynic with a sense of humor. He was a pessimist who loved photographing puppies.

Nor did his fears about the future lead him to facile detachment from society or civic duty: he maintained a close friendship with the first elected president of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Masaryk, himself a philosopher and writer. The two held a long epistolary correspondence which was later collected into a book, and Masaryk was a frequent guest at Capek’s salon-like gatherings.

Today, most of Capek’s limited contemporary fame comes from a single word in a single play, R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), a satire about the promised scientific utopia and the clash of good-intentioned ideologies:

HELENA: It is said that man is the creation of God.

DOMIN: So much the worse. God had no notion of modern technology.– Prologue, p. 41

R.U.R. assured Capek’s immortality, although in a slightly inaccurate way. While writing the play, he struggled to find a new word for his artificial hominids, settling on the clumsy labori. His brother and frequent collaborator Josef suggested the much more felicitous robot, from the old Slavic stem rab-, suggesting labor or servitude. Practically overnight, a new word entered our common vocabulary.

When the Oxford English Dictionary claimed “robot” as his invention, Karel proved himself a class act: he wrote a letter explaining that his brother was actually the word’s creator, asking them to amend the entry.

Capek died at the tragically young age of 48, although it was probably for the better: his death came on the eve of World War II, and his vehemently anti-Nazi sentiments would not have ensured him a happy ending. His brother Josef was dragged off in a brutal march to a concentration camp, where he died in 1945.

A Catastrophe of Our Own Making:

ON DAMS OF MISSISSIPPI A THOUSAND MEN NOW AT WORK STOP IF ONLY STOPPED RAINING STOP WE NEED SPADES SHOVELS CARTS AND MEN STOP ARE SENDING HELP TO PLAQUEMINE THOSE BEGGARS ARE IN A FINE OLD MESS

Late in his sci-fi masterpiece War with the Newts, Capek envisions the American Gulf Coast being obliterated as a first sortie in the war between humanity and nature. Until 2005, this chapter had seemed a frightening fantasy – and I’m sure a generation or two from now, it’ll feel the same way. But at this moment in history, and for those connected to the tragedy of Katrina (we “celebrate” two years this week) the images ring too close to reality to read as comfortably and as innocently as when they were first written:

The whole coast from Port Arthur (Texas) as far as Mobile (Alabama), it was said, had been inundated during the night by a tidal wave; everywhere could be seen wrecked or damaged houses. The south-east of Louisiana (from the Lake Charles-Alexandria-Natchez road) and southern Mississippi (as far as the Jackson-Hattiesburg-Pascagoula line) was plastured over with mud… The most serious loss of life would most likely have been along the coast.

– p. 304

In the novel, the destruction is not the result of a powerful hurricane, but of the human race’s idiotic attempt to master nature, here represented by a newly-discovered species of intelligent salamanders (Capek uses the term interchangeably with “newts”). Enslaved, subjected to experiments, and forced into manual labor, the newts eventually discover their ability to organize and fight back.

Why the Gulf Coast? Well, Capek understood a bit about the racial politics of the United States, and the newts’ treatment as a lesser species sometimes mirrors the post-war South’s treatment of people of color. See if you don’t get chills when newts are lynched after women accuse them (somewhat ridiculously) of rape, or at the minstrel show “Sally and Andy, the Two Good Salamanders”.

Why the Gulf Coast? Well, Capek understood a bit about the racial politics of the United States, and the newts’ treatment as a lesser species sometimes mirrors the post-war South’s treatment of people of color. See if you don’t get chills when newts are lynched after women accuse them (somewhat ridiculously) of rape, or at the minstrel show “Sally and Andy, the Two Good Salamanders”.

I’m making this novel sound grim and despairing, but it’s actually a rich work bursting with humor, literary experiment, and genuine affection for a misguided race that can’t help but screw up its own planet. Capek packs the pages not only with straightforward narrative, but with scientific papers, newspaper articles, illustrations, allegory, telegrams (see above), depositions, advertisements, interviews with real-life celebrities … and finally, the novel disintegrates in the epilogue, as an uneasy reader criticizes the author for having such an apocalyptic vision.

The fictional author pleads that it isn’t his fault for following the story to its logical conclusions. In a tirade that’s gained a lot of unintentionally accumulated meaning thanks to the global climate debate, he begs the reader to understand why he can’t save the narrative from the people who inhabit it:

They all had a thousand absolutely sound economical and political reasons why it’s impossible. I’m not a politician or an economist; I can’t change their opinions, can I? What is one to do? The earth will probably sink and drown; but at least it will be the result of generally acknowledged political and economic ideas, at least it will be accomplished with the help of the science, industry, and public opinion, with the application of all human ingenuity! No cosmic catastrophe, nothing but state, official, economic, and other causes.

– p. 340

Newts remains arguably the best of Capek’s science fiction, but other works are worth exploring, as well. The most interesting from a political point of view is Factory of the Absolute (sometimes translated as The Absolute at Large), which shows how well-meaning ideologies can contribute both to gloomy dystopia and to the eventual destruction of the planet. In Absolute, businessmen, politicians, armies, and religions all fight to create a human paradise on Earth, and through the impossibility of this goal they all contribute unwillingly to the destruction of the very ideal they envision.

The Pursuit of Knowledge:

“You see that footprint over there?” said the snow-covered man, and he pointed at an impression about six yards from the side of the road.

“I see it; a man’s footprint.”

“Yes, but how did it get there?”

The other major concern of Capek’s art was epistemology: how do we know what we know? Though it’s a constant presence in his work, he explores this theme directly in two exceptional short stories, “Footprint” and “Footprints”.

“Footprint” has no real plot to speak of: two strangers cross paths in a snowy landscape and notice the print of a shoe in the middle of the snow. At first they attempt to explain the print’s appearance as a natural phenomenon (Did someone hop there? Did a bird drop a shoe?), but as each attempt fails, their ideas shift from the physical to the metaphysical, to the religious, and finally to the bare contemplation of a phenomenon that offers no explanation, and no excuse for being. The two strangers part ways, deeply moved by the experience.

“Footprints” was written later and feels a little more cynical. This time, the two characters are unable (afraid?) to contemplate the footsteps fully, so they settle into convenient fictions that allow them to sleep easily at night.

But random footprints are cake compared to the impossibility of knowing ourselves – and each other. In a trio of novels – Hordubal, Meteor, and An Ordinary Life – Capek dove headfirst into the delicious unknowablity of the human experience. In each the narrative mode is different – sometimes first person, sometimes split between multiple, conflicting narrators – as the author explores the slipperiness of identity, both internal and external.

On Madmen and Artists:

Things get a bit more complicated in his final novel, the powerful but baffling The Life and Work of the Composer Foltýn, an unfinished work which exists in English only in a difficult-to-find and inferior The Cheat. Capek again employed the multi-narrator model, but where he’d earlier used it to show the difficulty of pinning down a single life, here all the narrators agree: the self-made poet and composer Beda Folten was nothing but a sham. In chapter after chapter, we watch the title character lie, cheat, and steal his way into D-list celebrity, leaving his path strewn with wrecked lives.

Sounds simple enough, but Capek throws in some curveballs that make this easy reading highly suspect. First, Folten’s mania is practically clinical, which may absolve him from his moral shortcomings (insofar as we can’t really use a madman to derive moral lessons). Second, some of the characters develop a plan for revenge that turns out far, far crueler than any of Folten’s petty crimes: against all odds, he ends up gaining our sympathy because of their brutal mistreatment of him.

So what exactly are we supposed to derive from that?

I’ll be honest: I have no idea, and that may be due to the unfinished nature of the work (although I doubt it – his widow described what he’d intended with the remaining chapters). What I can say is that it’s the best-written and most involved of all his novels, equally adept at humor and pathos, often within the same short chapter. Despite being in his deathbed, Capek was firing on all cylinders here.

Here’s a great example: in the wonderful third chapter, Folten’s college roommate – a pedantic older student, now Dr. V. B. – remembers how he blasted the young composer’s pretentious use of fuzzy, romantic terms to describe his “art”:

Whenever I hear or read that kind of prater about spiritual crystallization, formative pre-essence, creative synthesis or whatever they call it, it makes me ill. My God, people! I think to myself, stick your nose into some organic chemistry (not to mention mathematics) and you would be hard pressed to write at all. For me, that’s the greatest calamity of our time: on one hand, our ability to work with microns and infinitesimal quantities with a precision nothing short of perfection; and on the other hand, we’ll let our brains, our feelings, and our thoughts be controlled by the haziest words. I’ve always understood music; I felt in it something like a great and pure architecture, like one finds in numbers; but occasionally something disgustingly and cuticularly human creeps into it.

I can’t tell you how much I enjoy that final line, with its perfect neologism “cuticularly” (pokožkove). Working within the constraints of a developing language, Capek had excellent taste to know when a new word was warranted, and the disgust of the anti-social Dr. V. B. feels perfectly expressed by the dead skin of fingernails. Of course, the Doctor is right: Folten has no idea what he’s talking about, so he hides behind a bunch of grand-falutin’ words and ideas that he hardly understands.

The payoff is even better. Hating each other intensely, Folten and Dr. V. B. live “with knives drawn”, and finally the sham artist figures out how to avenge himself on his roommate. Implying that he’d slept with the Doctor’s love interest, Folten pounds out a mockingly bawdy tune on the piano. The intensely angry and humiliated Doctor loses his ability to express himself in that precise language he so treasures:

It was as if he had punched me in the face. It was a vulgar, cooing melody, an execrably crawling and oozing lasciviousness.

Foltýn only squinted his eyes against the brightness and played, played, played that whiny waltzing beastliness, swinging his whole body, with his mouth contorted, with an air of intoxicated fervor. I knew that he was slandering Pavla with that filth, that he was disrobing her in front of me, that he was mocking me: she was here, she was here, and the rest… well, you know. “You son of a bitch!” I bellowed.

Capek died while finishing one of the final chapters, written from the point of view of a “true artist”, the voice teacher Jan Trojan. What begins as another encounter between the narrator and the sham Folten slowly turns into a manifesto about the nature of art. Trojan uses the book of Genesis as a metaphor for art: not just God the creator, but a specific attitude towards the creative process:

I’m no scholar – only a simple musician, but this is what it means to me: in the beginning, it’s only you, formless and empty material; you yourself, your “I”, your life, your abilities, all that is only matter: there’s no creation, only empty existence…You have to divide light from darkness, so that the materials take shape; you have to divide and constrain so that clear contours emerge and things stand before you in full light, as beautifully as on the day of their creation. You create only up to the point that you give shape to the material: to create is to break down and always, always to design finite and concrete limits in the material, which is otherwise limitless and empty.

The last words Capek ever wrote were a plea to would-be artists: the material is already all around you. Your job is not to create more material, but only to lend the existing material clarity and shape.

In a rapidly-changing, chaotic interwar Europe, that’s precisely what Capek did.

Links:

– Complete online texts of R.U.R. and War with the Newts at eBooks@Adelaide

– The Karel Capek website, which includes an extensive biography

– Karel Capek at kirjasto

– Films based on Capek’s works, from the Internet Movie Database

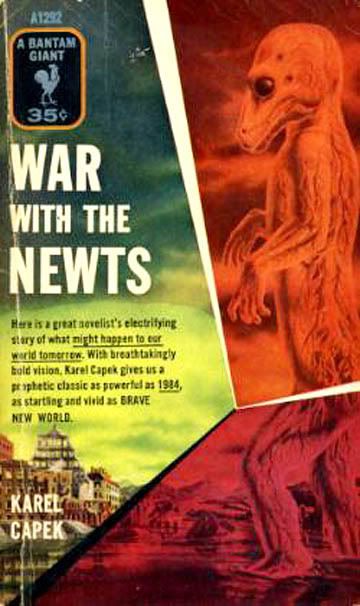

Excerpt from “Footprint” and the Arthur Miller quote taken from Toward the Radical Center: a Karel Capek Reader, Catbird Press. Excerpts from War with the Newts taken from the Northwestern University Press edition, translated by M. & R. Weatherall. Translated excerpts from Foltýn are my own. All images from Wikimedia Commons; the book cover of War with the Newts comes from the 1955 English-language edition (Bantam #A1292). Crossposted at dailykos and Progressive Historians.

17 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

We travel back to 19th century America to peer into the complex world of our most popular reclusive poet. How did a public-averse young woman become the grand dame of American poetry? Find out when we wrestle with the brilliant work of Emily Dickinson.

Author

The name Capek has a hacek (or “caron”) over the C, but the site doesn’t allow that letter for some reason. His name should be pronounced CHA-peck.

Another hole in my education.

Sounds like my kinda guy! I will have to go and bookmark the links….and hope someday I start reading something other than blogs again!

Thanks p!

ive been reading this for hours, have to keep getting up and then coming back to it. thanks for introducing me to this body of work.

tomorrow = me + used book store

Reading blogs jades you… it’s easy to be fast, to miss some lines…you know most of it anyway… it is, as Capek said, another light shone on already existing material… but it’s material you’ve been cramming into your brain day after day…

but this i had to stop. and read. like real honest-to-god reading. and every time i read like that, i remember why i love it… thank you pico for this wonderful essay and for introducing me to Capek…

After reading… Second, some of the characters develop a plan for revenge that turns out far, far crueler than any of Folten’s petty crimes: against all odds, he ends up gaining our sympathy because of their brutal mistreatment of him.

You ask: So what exactly are we supposed to derive from that?

i thought of The Scarlett Letter and how revenge perverted Roger Chillingworth. I realized after some time thinking about it, that even those wronged can become the monster… when transformed by revenge and hate.

Your Folten, it seems from this brief encounter, wasn’t a monster, just selfish, self-centered…

so i think it plays to our innate perception of proportionality (something we know but don’t understand the knowing of it), which may account in some ways for our understanding of justice…

warm regards… pf8

the reason it was so mind-blowing to me, his treatment of Hester and Roger is this: the time in which he wrote it.

seeing it in that context added, for me, a power to the story about transcending one’s time or place or convention

and there is the drumbeat of so many others, still reverbating and disturbing us…