Greetings, literature-loving DocuDharmists (do we have a name for readers yet?), and welcome to the latest installment of my series on writers great and small, ancient and modern, popular and obscure. Last week we spent time with the grand dean of Czech literature, Karel Capek, and watched him weave his humanistic philosophy through a dizzying mix of comedy, science fiction, and drama. This week’s subject stuck mainly to one genre – lyric poetry – but she used her deceptively simple lines to open a world of equally dizzying complexity.

If you think you know everyone’s favorite New England agoraphobe, think again! Let’s jump back to 19th century Amherst for tea and sympathy with one of America’s leading poetic voices.

I can wade grief,

Whole pools of it, –

I’m used to that.

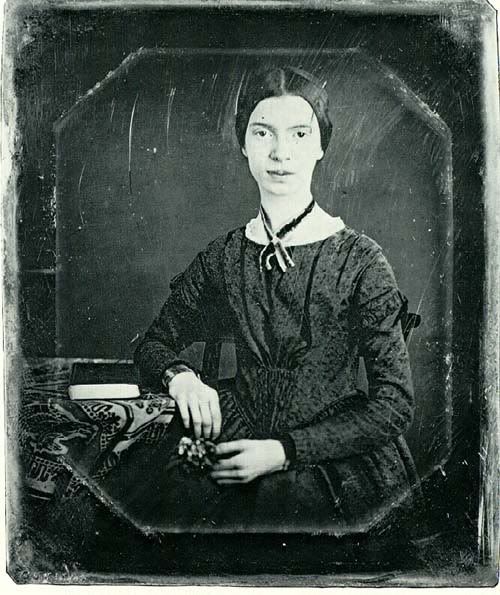

Mention the name Emily Dickinson, and you’re likely to hear a few vague biographical comments about a shy woman who never left her house, a recluse who became a sensation long after her death. As with her contemporary Walt Whitman, the myth looms larger than the person, and it still informs the reading of her poetry, often written on scraps of paper shoved in bedroom drawers, undiscovered during her lifetime.

The real Emily Dickinson was a bit more complicated, although certainly no well-traveled socialite. Daughter of a U.S. Congressman, Dickinson did spend most of her life in her family’s home, but she also briefly attended a nearby Women’s Seminary, was a close student of botany with a reputation during her lifetime for her immense knowledge and skill of gardening.

The real Emily Dickinson was a bit more complicated, although certainly no well-traveled socialite. Daughter of a U.S. Congressman, Dickinson did spend most of her life in her family’s home, but she also briefly attended a nearby Women’s Seminary, was a close student of botany with a reputation during her lifetime for her immense knowledge and skill of gardening.

Most of her poetry was discovered and published after her death, although even then fame was not forthcoming. Readers and critics were slow to pick up on Dickinson, in part because English-language poetry was going through a period of radical redefinition; Walt Whitman had exploded through America with his powerful free verse, and soon Ezra Pound and T.S.Eliot would be laying the groundwork for the highly experimental 20th century.

It didn’t help that her publishers were toning down her work. Confused by her innovative use of punctuation and her occasionally strange syntax, well-meaning family members and editors “corrected” her writing, removing all the idiosyncratic dashes and capital letters that we now expect and love (brilliantly parodied by Francis Heaney in the anagram poem “Skinny Domicile”). Another generation passed before readers saw the raw Dickinson, thanks to the efforts of a later editor, Thomas Johnson, and a later poet who advocated on her behalf, Conrad Aiken.

Nowadays Dickinson is the undisputed queen of American poetry, and perhaps the most popular of all our native poets, male or female. Why does she seem to appeal to readers on a much more basic level than any other American poet? Part of it has to do with her use of meter and rhyme, which lends her verse a “catchier” sound than most. Let’s take a quick look at how she does it…

(If reliving high school poetry scansion isn’t your idea of a good time, you’re welcome to skip to the next section.)

Like many great poets in the English language, Dickinson writes predominantly in iambs (da DUM!) Though it’s the rhythm most closely associated with everyday speech, other iambic poets like Shakespeare bring a lot of variation to keep it from sounding redundant; Dickinson exploits the repetition to lend her verse a snappy, memorable lyric quality.

Her most common and successful pattern is known as ballad meter, which consists of alternating four-foot iambic lines with three-foot iambic lines. In other words:

da DUM, da DUM, da DUM, da DUM

da DUM, da DUM, da DUMThe miracle of Dickinson’s verse is that she can stick to this rigid design without it ever sounding like the stilted lines that so many of us would-be poets produce when trying to get the rhythms just right. Dickinson’s roll off the tongue with unforced naturalness (there’s only one subtle variation in the following quatrain):

She sweeps with many-colored brooms,

And leaves the shreds behind;

Oh, housewife in the evening west,

Come back, and dust the pond!Dickinson is by no means the only poet to use this form, but she is its undisputed master. This ability to harness rhythm and rhyme so artlessly is what makes her the lyric poet par excellence, and one of the reasons her lines stick in your brain like the catchiest of song lyrics.

Pop Quiz: Which poem excerpts in this diary use ballad meter?

The first published volumes of Dickinson’s poetry were organized loosely according to “themes”: Life, Nature, Love, Time and Eternity, and The Single Hound (the latter is a reference to this poem). It’s true that these themes appear often in her poetry, although the too-narrow categorization obscured other areas of interest that occur throughout her life and work.

So I’ll take a slightly unusual tack and not talk about the areas of her poetry that she’s famous for. Most readers are already familiar with her rides with death, her debauchees of dew, her prudent microscopes, and her publicly croaking frogs. Let’s spend some time exploring the other Dickinson, who puzzled out the strange relationship between language and experience, who wrestled with metaphysics through Donne-like paradoxes, and whose religious convictions found their most interesting expressions when they were peppered with doubt.

I want to explore the Dickinson that made curmudgeonly critic Harold Bloom, not usually known for his hyperbole, write this:

Emily Dickinson had the inner freedom to rethink everything for herself and so achieved a cognitive originality as absolute as William Blake’s.

That’s a strong claim towards a poet sometimes derided for the very catchiness that makes her so memorable, and I want to explore this “cognitive originality” more in depth.

In the Beginning was the Word:

Poets write poetry (obviously) so it’s no surprise that many poets write about poetry as well, especially the ability – or inability – of poetry to capture experience. This gap between language in life isn’t unique to literature: how many times have we stood gaping at the beauty of the natural world and repeated that hoary cliché, “I just can’t put this into words”? Dickinson feels our pain:

Nature is what we know

But have no art to say

The world of experience, especially as applied to the outdoors, finds only an imperfect translation in poetry. What’s ironic here is that Dickinson is nonetheless well-known for having been among the best of translators: her precise illustrations of the natural world are one of the reasons for her enduring popularity. Unlike Symbolist poets, who were popular around the time she was being published, Dickinson is never vague in her descriptive language: her ideas may be difficult to understand, but her images are striking for their clarity and precision:

An everywhere of silver,

With ropes of sand

To keep it from effacing

The track called land.

But something is always out of reach, a feeling that words cannot capture. This limitation of language was a common trope in 19th century poetry, but unlike many of her peers Dickinson also understood that the reverse is equally true: language is rich and boundless, and sometimes beyond the ken of the person using it:

Could mortal lip divine

The undeveloped freight

Of a delivered syllable

‘Twould crumble with the weight.

Language here is more than an imperfect vessel of experience: it has an independent life far more complex than the experience it’s attempting to translate. For 21st century readers raised on Saussure or Derrida, this isn’t surprising, but the Dickinson predates them both. In Western thought, language – especially the written language – has always had a certain stigma attached to it.

Language here is more than an imperfect vessel of experience: it has an independent life far more complex than the experience it’s attempting to translate. For 21st century readers raised on Saussure or Derrida, this isn’t surprising, but the Dickinson predates them both. In Western thought, language – especially the written language – has always had a certain stigma attached to it.

One side of that stigma is religious, with a long Western tradition of lamenting the inferiority of human language since the whole Tower of Babel debacle. Another side came from the association of language with civilization (and thus in opposition to nature), which lead philosophers like Rousseau to argue that written language, the most artificial of all, was therefore the least genuine.

But Dickinson understood that the Word carries its own power, and she upbraids those who treat it as an inferior art while granting it a level of independence that would make 20th century semioticians smile:

A Word is dead

When it is said,

Some say.

I say it just

Begins to live

That day.

From Word to Thing … to Beyond:

She doesn’t stop there. Dickinson acknowledges not only the gap between signifier and signified – to use the 20th century terms, but also the gap between the thing perceived and the thing itself (the connections between Dickinson and Kant are just beginning to be explored):

Perception of an Object costs

Precise the Object’s loss.

Perception in itself a gain

Replying to its price;…

The Object, like the Divine, is beyond direct contemplation – it has to be filtered through merely human experience. But despite her religious convictions Dickinson’s sympathies often lie with this imperfect human world:

…The Object Absolute is nought,

Perception sets it fair,

And then upbraids a Perfectness

That situates so far.

The distance between the demands of the Absolute (or the Divine) and the fallibility of our mortal coils casts an occasional dark shadow over her religious verse. In general Dickinson expresses her faith exuberantly, if not naively. Her Christianity, a combination of Puritanism and transcendentalism with a healthy dose of earthy nature-lovin’, situates salvation as a difficult but worthy goal of the well-lived life:

Glee! The great storm is over!

Four have recovered the land;

Forty gone down together

Into the boiling sand.Ring, for the scant salvation!

Toll, for the bonnie souls, –

Neighbor and friend and bridegroom,

Spinning upon the shoals!…

But doubt is a more powerful artistic theme than faith, and some of her most powerful poetry allows for that discomfort of not-knowing, or even of disapproval. The poem above continues,

…How they will tell the shipwreck

When winter shakes the door,

Till the children ask, “But the forty?

Did they come back no more?”Then a silence suffuses the story,

And a softness the teller’s eye;

And the children no further question,

And only the waves reply.

Notice we’ve come full-circle back to the limits of language: only silence and the sound of waves can express the feeling that the Saved will have for the Unsaved. Of course there’s an irony here, since she’s nonetheless using words to describe that silence. So we return to our original critique of language: how can words express what is beyond the power of words to express?

Contemplating the Absolute:

There are ways to do it, of course. Dickinson’s approaches to discussing the ineffable are indirection and paradox: on occasion her metaphysical musings remind one of John Donne more than any of her contemporaries.

For example, she is constantly amazed by the expansive endlessness of the soul, which is nonetheless a tiny and contained part of the tiny and contained human being:

There is a solitude of space,

A solitude of sea,

A solitude of death, but these

Society shall be,

Compared with that profounder site,

That polar privacy,

A Soul admitted to Itself:

Finite Infinity.

“Finite Infinity”, she writes: the paradox of the interior life more expansive than the exterior life, which nonetheless contains it. In poems like these, Dickinson isn’t merely playing games with the language (although she does recognize and exploit language’s capacity for paradox); the ideas themselves are difficult to resolve.

The Soul is one target of major inquiry in her poetry – the Great Beyond is another. Whatever paradoxes we may encounter when turning inwards are nothing compared to the promised hereafter:

My life closed twice before its close;

It yet remains to see

If Immortality unveil

A third event to me,So huge, so hopeless to conceive

As these that twice befell.

Parting is all we know of Heaven,

And all we need of Hell.

I’ve read this poem a thousand times, and it’s among my favorites… but I’d be lying if I said I understood it. The language is simple and straightforward, but the ideas are elusive: why does Immortality offer a third “close” (which isn’t death, but after death)? Why is parting what we “need” of Hell, which seems counterintuitive?

And yet her words resonate like Thunder (“So huge, so hopeless to conceive”), and the poet sometimes derided for her tuneful, catchy lyrics leaves us all in her wake. Like a snake charmer she hypnotizes us with her music, but there’s never any doubt who’s in charge.

That shy woman of Amherst may not have traveled around the world or rubbed elbows with the great minds of her generation, but few people have simultaneously charmed us and challenged us, and her popularity with contemporary readers is well-deserved. For the seductive power of her words, Emily Dickinson is practically a force of nature:

To pile like Thunder to its close,

Then crumble grand away,

While everything created hid –

This would be Poetry

Links:

– The Dickinson Electronic Archives (a personal favorite, “Emily Dickinson: Cartoonist“)

– The Complete Poems (1924 edition) at bartleby.com

– website of the Emily Dickinson Museum

– Emily Dickinson at kirjasto

– The Daily Dickinson (poems and discussions for every day of the year)

All images are in the public domain, courtesy wikimedia commons. Excerpts are taken from the 1924 edition of the Collected Poems as a matter of personal convenience, but I’d recommend a later edition if you’re looking to buy a collection of her poetry. Cross-posted at Progressive Historians and Dailykos.

Thanks for reading!

28 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

we’ll come back to the 20th century and allow ourselves to get lost in the twisted, endless corridors of an Argentinian labyrinth, courtesy of Jorge Luis Borges!

With a hat tip to Kerouac, may I suggest dharma bums?

I consider this an obligatory comment in any discussion about E.D. I’ll just let Garrison Keillor explain it…

Of course, a lot of her poems can be sung to the tune of Gilligan’s Island Theme too.

her herbarium has been published in facsimile. Although at $125, I might wait until it shows up remaindered or used somewhere (currently $90 even at Amazon), it would be fascinating to me.

though I don’t like to admit it, I am almost completley ignorant when it comes to poetry.

Thanks for the free lessons.

about the poem you quote near the end, “My life closed twice before its close;”

That you’ve read often. I agree it’s quite . . . cavernous? Awe-some?

It reads to me like she is mourning the death of two loved ones. Is that a standard reading? After reflecting on it for so long, what do you think?

If only others had your taste.

The Road To Paradise Is Plain

The Road to Paradise is plain,

And holds scarce one.

Not that it is not firm

But we presume

A Dimpled Road

Is more preferred.

The Belles of Paradise are few –

Not me – nor you –

But unsuspected things –

Mines have no Wings.

excellent work, as usual, pico. thanks.

what books Dickenson kept around her place.

I could at least spell her bloody name right.

worry about me!

I am kidding of course.

not long ago, right? Repost it here; I loved it.