Greetings, literature-loving Dharmiacs! (or whatever you’re called) Last week we danced with the Dame of Amherst and found that she had a few crafty tricks up her embroidered sleeve. This week we’ll continue with our theme of mind-twisting literature, but we’ll first relocate to a slightly warmer climate:

The setting is Buenos Aires, the time is the 20th century. A blind seer is guiding us around the labyrinthine National Library, spinning yarns on everything from gauchos to Gargantua. But how much of it is true, and how much of it is a devilish game? Have we been wandering around a library with no exit?…

Follow me below through the twisted paths of Argentina’s most famous fabulist.

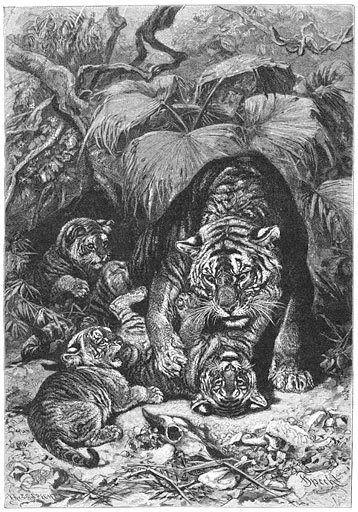

As I sleep I am drawn into some dream or other, and suddenly I realize that it’s a dream. At those moments, I often think: This is a dream, a pure diversion of my will, and since I have unlimited power, I am going to bring forth a tiger.

A quick anecdote to introduce this installment:

A few years back I was teaching a course in, appropriately enough, great literature. After I mentioned something Borges wrote about Dante, one of my students interrupted: “Why do you always quote Borges, no matter what we’re talking about?” I replied, “Honestly, because Borges has something interesting to say about everything.”

And it’s true. Borges was probably the best- and broadest-read writer in history, a contemporary Pico della Mirandola who excelled equally in prose, poetry, and nonfiction – and often delighted in blurring the borders between them. Despite his enormous influence, fanatically devoted readership, and undoubted contribution to 20th century thought, he’s consistently neglected in lists of great writers of the last century.

There’s a reason: literary history is heavily biased towards the novel, and despite his impressive creative output Borges wrote none. We’ll see the same problem when we come to Chekhov, who I’d argue is a greater writer than Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, but languishes in comparatively B-list celebrity.

But I’ve started down the wrong fork in this path-filled garden. Let’s back up a bit and acquaint ourselves with the literary Augur of Argentina.

The Dreamer:

I’m not sure which of us it is that’s writing this page.

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo entered the world in the last year of the 19th century and nearly outlived the 20th. Literary history is filled with wunderkinder who churn out early masterpieces and flame away in their 20s; Borges’ flame was a slow and steady burn. In the course of his life he witnessed two world wars, the birth of cinema (he wrote film criticism before film criticism was popular), the decline of the British Empire and the ascent of the United States, and a South America whose improbable changes rival anything in a García Márquez novel (and García Márquez would probably agree).

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo entered the world in the last year of the 19th century and nearly outlived the 20th. Literary history is filled with wunderkinder who churn out early masterpieces and flame away in their 20s; Borges’ flame was a slow and steady burn. In the course of his life he witnessed two world wars, the birth of cinema (he wrote film criticism before film criticism was popular), the decline of the British Empire and the ascent of the United States, and a South America whose improbable changes rival anything in a García Márquez novel (and García Márquez would probably agree).

From the beginning, Borges had a love of the romantically down and dirty, of knife-fights and street gangs. In his first works he slyly chronicled semi-fictional accounts of bandits, murderers, and thieves in his collection A Universal History of Infamy. Though certain Borgesian elements are already present (especially the wicked blending of fiction and nonfiction), he owes much of his literary development to a head wound, a distinction he shares with writers like William March, Theodor Körner, and Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

That’s a little reductive, but sometimes the myth runs more smoothly than the fact. Borges had written one of his ‘new’ stories before the accident (“The Approach to al-Mu’tasim”), but it was while recovering from near-fatal septicemia that followed that he wrote most of the dizzying collection of stories published as The Garden of Forking Paths. Though they failed to attract much attention in 1941, the collection has since become the cornerstone of Borges’ prolific output.

Then his eyesight began to fade. Despite this, he worked tirelessly as an author, translator, and lecturer, accumulating enough notoriety to be appointed head of the National Library in 1955 – by which time he’d become totally blind. (Fans of Umberto Eco might recall the blind librarian in The Name of the Rose, “Jorge of Burgos”.)

He continued to churn out stories, poems, essays, and lectures until his death in 1986. Despite his considerable reputation as one of the world’s best and most important authors, he was never awarded the Nobel Prize – although he might have enjoyed the company of other non-winners like James Joyce, Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, etc.

Orbis Tertius:

In the beginning of literature there is myth, as there is also in the end of it.

Because Borges was so prolific, I’m not exactly sure how to approach discussing his works. In the universe of his Ts’ui Pen, I’d have “a growing dizzying web of divergent, convergent, and parallel” diaries to discuss them all; unfortunately the demands of this time (and the server capabilities) require me to choose only one, specific handful of tales.

Most (but not all) of these short capsules that follow come from his collection The Garden of Forking Paths, since they were the most influential of his works. Borges was heavily influenced by mythology (both western and eastern), by the 1001 Nights, by Dante, Kipling, Joyce – in return he left his stamp on Eco, Pynchon, Rushdie, Perec, Barth, Danielewski, García Márquez, Fuentes, and many others.

Notice that many of his tales center around a single, complex idea: he then spins the idea into a web of the fantastic, and the result looks something like an essay, or something like a fable. But where many writers are satisfied with idea itself, Borges continues pushing it to discover more and more of its consequences:

- “The Library of Babel” is one of his best known stories, a dream (or nightmare) told as a sober report from an alternate universe whose laws are completely unlike ours. This Library is seemingly infinite, but contains a finite number of books: namely every interpolation of every combination of every letter, space, and punctuation mark in every language, real or invented:

Everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels’ autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.

This is typically Borgesian: a fanciful idea, treated with all seriousness, taken to its logical conclusions.

But the Library of Babel is more Hell than Heaven (elsewhere Borges called it a “subaltern horror”). Because it contains every interpolation of written symbols possible, nearly all the books are nonsense collections of letters; you could browse your whole lifetime without finding a single book that made sense. Because everything exists on its shelves – including this diary, with your comments! – we cave under the immense power of this overwhelming completeness:

To speak is to fall into tautology. This wordy and useless epistle already exists in one of the thirty volumes of the five shelves of one of the innumerable hexagons — and its refutation as well.

For a similarly dark tale about what happens when ideas are taken to their extreme, check out “The Lottery at Babylon“, a parable about the role of chance in gambling. If chance is the fundamental mark of gambling, what happens when the rules themselves are subjected to chance?

- “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” exists in that uncomfortable region between fiction and nonfiction that so marks Borges’ best stories. Like his tales “Pierre Menard” or “Three Versions of Judas”, it can be read side-by-side with his nonfictional essays on P. H. Gosse or Ramon Llull, and unless you knew the difference you’d never guess which were fact and which were fiction.

“Tlön” posits an imaginary encyclopedia that charts, in exquisite detail, everything that a typical encylopedia would cover – albeit of an imaginary planet whose inhabitants’ cognitive processes are completely unlike ours. Borges begins with a race who conceptualize the universe according to time rather than space, and he spins out a whole history of languages, divergent philosophies, and sciences that would arise on the planet (or rather, Borges the fictional narrator explains what he reads in the real, but fictional encyclopedia. Confused yet? It gets worse.) In the postscript, the narrator warns us that the seductive fictions of Tlön are invading the ‘real’ world and beginning to usurp our own reality.

“Tlön” posits an imaginary encyclopedia that charts, in exquisite detail, everything that a typical encylopedia would cover – albeit of an imaginary planet whose inhabitants’ cognitive processes are completely unlike ours. Borges begins with a race who conceptualize the universe according to time rather than space, and he spins out a whole history of languages, divergent philosophies, and sciences that would arise on the planet (or rather, Borges the fictional narrator explains what he reads in the real, but fictional encyclopedia. Confused yet? It gets worse.) In the postscript, the narrator warns us that the seductive fictions of Tlön are invading the ‘real’ world and beginning to usurp our own reality. So what do we make of the real-life Second Edition of the Encyclopedia of Tlön? (h/t Bastouche) As far as I can tell, it’s a nonfictional fiction referencing a fiction about a nonfictional fiction. Borges would be delighted.

- Many of his stories are more straightforwardly “fiction”, although no easier for it: “The Circular Ruins” feels like the rebirth of myth in an apocalyptic modern era. It’s a twisted retelling of the Pygmalion, with an unknown man in an unknown country practicing secret rites in the creation of another being, who at first exists only in his dreams. In the shadow of ancient ruins, human consciousness is tested by fire.

The function of dreaming-as-creating is a recurrent theme in Borges’ work: the quote about tigers that began this essay comes from a short work “Dreamtigers“, which laments our inadequacy as dream-creators. Like the Demiurge, we realize too late that our creations are imperfect and unsatisfactory.

- “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” hooked me on Borges for good. The ‘story’ is presented as an obituary for a second-rate writer who nonetheless produced one work of weird genius: Don Quixote, word-for-word exactly as Cervantes had written it some three hundred years before. Menard’s is not a copy of the original but its own work, and Borges subjects both versions to his talented critical eye:

Cervantes, for example, wrote the following (Part I, Chapter IX):

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor.

This catalog of attributes, written in the seventeenth century, and written by the “ingenious layman” Miguel de Cervantes, is mere rhetorical praise of history. Menard, on the other hand, writes:

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor.

History, the mother of truth! – the idea is staggering. Menard, a contemporary of William James, defines history not as a delving into reality but as the very fount of reality.

The humor is pretty clear, but the depth of the critique takes some time to process. On one level Borges is describing the way we filter texts through our understanding of contexts, but on another level he’s poking good-natured fun at it. Is he advocating this kind of reading, or debunking, or merely observing? Far from being a peripheral concern, this tension between text and context is at the very center of reading, and after wrestling with “Menard” you may find it difficult to read any text in quite the same way again.

- By the time we get to “Borges and I“, from which the quote above (“I’m not sure which of us…”) was taken, the usual categories of fiction and nonfiction are no longer valid – in fact, most of what’s collected in The Maker (sometimes translated as Dreamtigers) resists categorization. Here the nonfictional Borges discusses the way his identity has slowly been usurped by the author Borges, a literary persona who sucks the life out of the ‘real’ Borges, even as he sustains him. But we’re faced with a paradox: the story can’t have been written except by the writer, so are we reading a cry for help or an elaborate game? Or both?

The narrator of “Shakespeare’s Memory” gets a little more respite… maybe. Tricked into accepting the Bard’s memory as a gift, he finds himself containing two sets of memories and unable to balance them both in one head. The story, Borges’ last published, contains word-for-word echoes from “Borges and I” and addresses the same concerns of authorial identity, but on a more communal scale. Does he finally manage to dispose of the other, or as he suggests in other articles, do the fleeting thoughts of other authors – of all authors – float through all our memories in a sort of collective haze? Is Whitman really de Quincey, Menard really Cervantes, Borges really Borges?

I could go on, taking each story and each essay in its turn, but this diary would begin looking suspiciously like that Infinite Library, which nonetheless contains it. There’s so much more to discuss, like definitive proofs that Judas Iscariot was actually God, brief refutations of time, languages that refuse even the same word for the same object at different moments, theories of an infinite string of divinity that’s constantly in search of its superior, maps so accurate that they contain the maps themselves, and fantastical systems of categorization taken from ancient Chinese encyclopedias. I won’t even tell you which of those are fictions and which are nonfictional essays… Does it really matter? To enter Borges’ universe is to experience a new way of thinking.

Mind-bending games aside, there’s a sweetness to Borges and a love of everyday magic that prevents his work from seeming like cold intellectual exercises. Borges is fundamentally a dreamer, and this brief anecdote describing an event near the end of his life sums him up pretty well:

His travels continued, and accompanied by María Kodama he journeyed around the world and compiled a travel atlas – he provided the text, and she the pictures. The resulting work, Atlas, was published in 1984, and presented their journeys as an almost mythical voyage of discovery, a travelogue through both time and space. It was during these travels that he finally had the chance to fulfill a childhood dream – stroking the fur of a living tiger.

|

Links:

– The Garden of Forking Paths, an outstanding set of Borges resources from The Modern Word

– Borges capsule at kirjasto

– Online texts of a few stories and essays, at Swarthmore College

– The Borges Center at the University of Iowa

– The Borges Collection at the University of Virginia

– A discussion of Borges’ fantastic Classification of Animals, with notes about its influences

– Previous installments of Profiles in Literature

Borges aficionados are lucky: Penguin Books published an outstanding three-volume collection of his works: these are must buys. Most of the excerpts above were taken from the Collected Fictions, translated Andrew Hurley; but don’t miss the Selected Nonfictions (a well-worn copy of which sits on my nightstand) and Selected Poetry. Excerpts from “The Library of Babel” and “Borges and I” come from the Swarthmore site. All photos from wikimedia commons, with links to the source pages. Cross-posted at Daily Kos and Progressive Historians.

Thank you for reading!

32 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

I’ll be marching on D.C. this weekend with the Road2DC crowd, so dkos user xanthe will be taking the reins for a ride with Edith Wharton. I’ll try to get her to crosspost here, as well.

Cheers!

I think my favorite thing attributed to Borges is this quote: “I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of library.” But, I’ve never found what work of his its from. Do you know?

Anyway, it is a great quote for a lover of literature, books, and knowledge.

few, if any writers have ever impacted me the way borges did. he takes your mind apart. he puts more into a short essay or story than most writers put into their entire bodies of work.

the day he died, my friend, and then sometimes writing partner, showed up at my little apartment. i opened the door, and all he said was:

“now, we’re on our own.”

I wanna play! Excellent diary, pico! I love Borges and I love pico’s diaries, and now I have to go back to work. Phooey!

see his influence everywhere. In philosophy of mind, for example, sometimes you will read a philosophy say, of the solution to the mind-body problem (modern variant: how do mental states relate to physical brain states?), that it is written down somewhere in Borges’s library. Then someone will say, perhaps there is no answer (these folk are called, non-insultingly, “mysterians”). Then, someone will raise what, to a philosopher, is the most terrible possibility: that there is an answer, but it’s not in Borges’s library.

Borges gave us new ways of thinking. “We’re all Borgesists now.”

Nobel Prize? A piffle.

things don’t have to happen in the concrete world to be true or even real… whenever i read a book of “fiction” it becomes real… and i am the one who slips away, becoming a shadow in someone else’s story… all this happening in the interior universe of my brain… acted out in some other plane

i read Gone With The Wind when I was eleven… and still, every once-in-a-while, wonder did she get him back… it is unresolved, and still happening…

i think Jung was right about what is real…

just ate my dinner and read and it was very relaxing, stimulating, and another writer i’ve only heard about but must read!

partial to Jose Saramango, as well. He doesn’t seem to get much ink here in NOrth America.

For once, that is the appropriate word.