According to one way of telling this story, the world began in 1641 with the following words, as translated from the Latin:

Some years ago now I observed the multitude of errors that I had accepted as true in my earliest years, and the dubiousness of the whole superstructure I had since then reared on them; and the consequent need of making a clean sweep for once in my life, and beginning again from the very foundations, if I would establish some secure and lasting result in science.

— Rene Descartes, 1641

The world ended — again, on one way of telling this story — as follows:

On or about December 1910, human nature changed.

— Virginia Woolf, 1924

In this essay I want to explore the meaning of those two passages, and to think about where we stand now in relation to them. Let’s ask what we should do after the end of it all, here at the end of the end of the world.

(Pictures, too! Below the fold.)

The beginning, here, as quoted above, was the beginning of Rene Descartes’ Meditations On First Philosophy. The end was marked by Virginia Woolf, upon the occasion of visiting an exhibition of post-impressionist art in 1910.

The world began like this:

Descrates, after famously musing upon the question of what he could be certain, decided that his foundation, his rock, was Cogito ergo sum — I think, therefore I am. That Descrates was anticipated in this by St. Augustine and 1300 years is beside the point. Nobody needed the cogito in 380 a.d. In 1641, they did. By 1641, religion had rather demonstrably and violently failed to ground the world in certainty. So . . . Descartes started again, closer to home. With me. With you. I think, I am. You think, you are. The rest had better follow from there.

And follow the rest did, in spades. From this foundation, this certainty in the stability and sufficency of the individual human, we get among other things the novel, the industrial revolution, capitalism, and the scientific method of verification. If I can see the carbon atom, and you can see the carbon atom, then it doesn’t matter if God can see the carbon atom. (And given the rate at which we see that atomic sucker decaying, it might be just as well if God doesn’t see it — the planet’s a bit too old for His liking.)

But then, if the world is based upon the stability of the subject — the human subject, the arbiter of all things, the standard measure, what are we to make of Nude Descending a Staircase #2 by Marcel Duchamp, at the beginning of the 20th century?

Where is the stability there? The center upon which to build Descartes’ lasting superstructure? What kind of life form sees itself like that? Who does that person think he, she or it is?

“On or about December 1910, human nature changed.”

There are other ways of telling this story. We can begin, if we want — if we prefer the concrete to the literary — with the English Civil war in 1642, and end with the Germans crossing into Belgium in August 1914. We can note, too, the eerie prescience of the poets, as if they saw the end of the world coming. As if they knew of the fragility of certainty and of the vacutiy of the solitude upon which it had rested.

Ah, love, let us be trueTo one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

— from Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach, circa 1851

A point about the historical tide noticed, as usual, by the poet before the general.

Our soldiers are individual. They embark on individual little enterprises. The German . . . is not so clever at these devices . . . He has not played individual games. Football, which develops individuality, has only been introduced into Germany in comparatively recent times.

— Lord Northcliff’s War Book, 1917

It is a symbol, I suppose, of the ignorance with which armies crashed into the oncoming darkness, that the Brits of WWI kicked footballs towards the enemy lines as they advanced. At least at first. But, to vary Woolf’s phrase: on or about August 1st, 1914, human nature changed.

We can wonder about the very notion of progress built upon that sand. We can marvel at the fact that the British kicked soccer balls — soccer balls! — into the nightmare no-man’s land, the barbed wire between the trenches of WWI, as a sign of “good sportsmanship”.

What we cannot do is doubt that something happened. However you want to begin this story, with Rene Descartes or Oliver Cromwell, with Hamlet or Adam Smith; however you want to end it, with Archduke Ferdinand or with Virgina Woolf. Something happened.

So what do you do at the end of the world? What do you do when you find, in end, only empty space, only nothing? What do you do when there is nothing left to say? Well, one answer, and it’s certainly not a bad answer, is: make a joke.

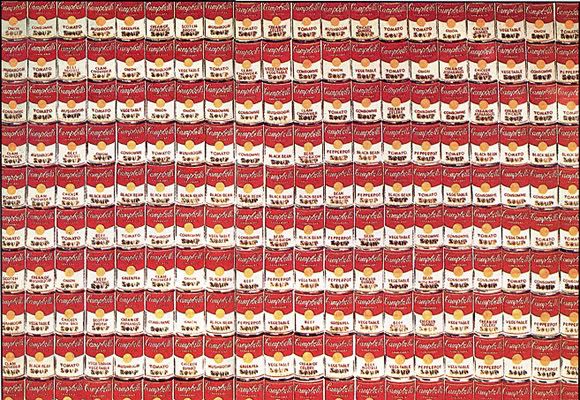

That was Andy Warhol’s answer, and, on one way of telling the story, we call this answer, “post-modernism”. Post-modernism is like the well-timed joke, the beat of the drum, the holding action until we figure out: what next?

What comes next?

This brings me to the phenomenon of George W. Bush. Or, rather, the phenomenon of his followers. George Bush, famously, does not get the joke, or that there is a reason to tell one. He is not post-modern. He is, if anything, pre-modern. He never got as far as Descartes did, in 1641. He never: “observed the multitude of errors that I had accepted as true in my earliest years, and the dubiousness of the whole superstructure I had since then reared on them”. Or if he did, if he did “sweep it all away,” he did it in the decidely humorless way, the retro-fit of the paleolithic, that we call being “born-again”.

“Born again”: a way of not getting the joke; a way of missing the point. A way of coping with the failure of the Modern that fails to grasp exactly why anyone was making a joke to begin with.

Or perhaps, “born again” is post-modern at one remove. For example, here’s an attempt at post-modernism that somewhat fails to convince:

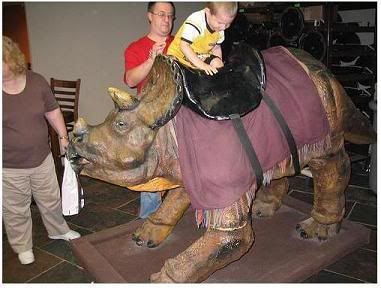

This is the celebrated “Jesus Horse” at the recently opened Creation Museum in Kentuky. And it is not a joke (even though it’s hilarious). It is, however, and however oddly, post-modern.

The Jesus Horse is part of the pause, the caught-breath before diving, the beat in the joke, that we call post-modernism. The joke about progress. The questioning, not of science but of scientism. The weeping over that football kicked into no-man’s land. That the proprietor of the creation museum doesn’t know this, is, again, beside the point.

George W. Bush is, in this way, the ultimate post-modern president. His fans are the apotheosis of accidental kitsch. Kitsch-value is what made the 60’s love the 50’s, the 90’s love the 70’s, and no one at all love the 80’s, except the idiots who don’t know that they really ought to be kidding when they say Reagan was a great President. George Bush is what you get when you don’t know what to do; he is the world-historical hiccup before the Next Big Thing. This is what I believe. If Virgina Woolf told us about the end of the world, then George W. Bush is telling us about the end of the end of the world. The last gasp of the modern era.

What do we do now? What do we do at the end of the end of the world? It’s not enough, anymore, to make jokes about the past. We have to actually try and make a future — a much scarier proposition.

Although I certainly hope the future has jokes in it, too.

Sitting alone in his house, with his table and his quill pen and his thoughts, the best Descartes could do was “I think, therefore I am.” Of course it was the best he could do — and good on him for trying. Descartes was, after all, thinking to himself. But in the blogosphere, we think to each other; just I, now, am thinking to you. The “We think, therefore we are” of the blogosphere is not the death of individuality. We are individuals, but our presense to each other has an immediacy and a meaning not present in other forms of writing. We are here. We are here, together. As individuals. Together. And we are not afraid to say so.

We feel, as did Descartes, “the consequent need of making a clean sweep for once in my life, and beginning again from the very foundations”, but we do it together, because we feel no worry, no need to re-assert, yet again, that we are ultimately alone. Maybe in the end we are: death will have its dominion. But for right now we are here, and we are doing our best.

The banner for Docudharma reads, “Blogging the Future”. This is what I take that to mean. Blogs are where we try, through rough draft and re-draft and re-re-draft; through comments and essays and snark, to think of the Next Big Thing. To try our best to see what it is we are supposed to do, here at the end of the end of the world.

37 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

Sunday afternoon. This is my first effort at a standard 4pm Sunday FP post. A dry run.

Lemme know what you think, okay?

a girl who’s just procrastinating for a minute from a paper due tomorrow (only 2 years late!)!!

A fantastic history of the beginning and the end of the world … and enfolded into it all of the central questions of meaning and being and trauma and aesthetics and politics.

I’ve got a million things I wanna talk about … but I’ll just start with Rene.

Descartes couldn’t get grounded in any event (and I love him for it!), even by seeing what remained after the hyperbolic doubt … it was all just a proleptic trick–making a companion of doubt in the first, and grounding the cogito in the second, so he could get to the real beginning–the proof of God in the third. Reassure himself, step back from the edge.

… and the Cartesian subject is already unstable, cleaved in two as a res cogitans and a res cogitatum, with a constitutive internal division and hiatus, so it can regather as a supposedly centered, self-possessed self-consciousness … but the split’s the thing. Even before we get to modernity.

From other convos, you might know that I’ve got some things I want to say about Shrub and pomo, but I feel the law breathing down my neck … and I’ve got to go back to my paper.

I’ll pop back in for a delicious snack in my next procrastination.

Kudos, LC, for a great, first, regularly-scheduled FP post. You’ve set your bar awfully high, hon.

P.S. I love this:

The structure of existence as that of survivorship–beyond the end of the world, together we still go on, impossibly, necessarily.

Namaste!

how few times he uses any stand-alone form of the verb to be. Mentioned not to give away any of your tricks. Over extended pages, the difficulties of going without start to mount, as they do in trying to write without the letter e its own proud self.

That I, that ego, always seemed to be pulled out of a hat. Much better I could buy thought, therefore existence or similar. Awareness, therefore existence.

—But you can’t help it! That’s the language!

Very well then, maybe language pulled the rabbit out. But still behind the screen of language there is nothing, including any eggoes or legos, antecedent to consciousness. Maybe there’s another kind of language.

Best of yours I’ve ever read. Stellar.

from another direction, Cartesian in origin.

My day job involves writing about spatial objects and how to store such data and how we interpolate points on a sphere.

So I’m exposing myself to Descartes from his mathmetical being – that you can determine any point from its X-coordinate and Y-coordinate. But, you see, he operated mostly from a flat-earth point of view. Determining vectors on the earth’s surface has been found to be much more difficult and less exact than Descartes calculated.

There is a challenge in being a point in a round world, you see. If you are to determine your orientation, as a point, it’s far easier to cut the world in half, in hemispheres. Then you have an “edge” to calculate from – a bounding margin if you will, and you can draw the coordinates for any point fairly easily within the limitations of a hemisphere on a sphere.

If you attempt to draw a circle, or a polygon around a point in a total sphere world, mathematics dictate that you have to determine the interior of the ring (to find your point) and the exterior ring (to find the orientation of the interior point and where it sits on a sphere.) Confusing? Maybe.

But imagine a world that is glaciated in an Ice Age. The surface of the earth is predominantly covered in ice and land, and the liquid water is limited in such a cold place. So you can create a polygon that describes the location of the small amount of liquid water, in relation to the larger polygon(s) of the frozen ice and land. Not so hard – one is larger than the other on the sphere.

But the ice starts to melt. Land is covered by water, lakes meet oceans, rivers meet lakes and become larger lakes, ice caps cover valleys, land masses disappear. Soon, we have only two topological elements (of two dimensions, at least): Land and Water. Now your water is the far greater of the polygons: you have disappeared one, the frozen ice, and you have reduced another – the land mass – by melting the ice.

The smaller polygon becomes the larger polygon, the liquid water. And crosses the hemisphere at the equator.

How, now, do you orient the same polygon of the water, when it has exceeded the edge and crosses over into the exterior of itself?

What is the inside of the polygon and what is the outside?

At what point do our interior thoughts become exterior thinking and intersect with several points on a nexus with other points?

Life is like a Venn diagram.

I’m not explaining this well. I obviously need graphics and a lot more work on the concept to get this point across.

I’m certain Rene is laughing now.

Sorry, LC, to go off on such a tangent.

Great example of an FP post for a Sunday.

… Hannah Arendt, in “The Life of the Mind” said something similiar to Woolf, but about philosophy — she noted after WWII that philosophy had “ended” but that there were “pearls” to be gotten by diving into the rich sea where the remains were buried.

I think that was another time where there was an ending — Arendt had studied under Heidegger (sp?), who turned towards the Nazis and the relationship was breached.

I also read a bio a long time ago about Franz Kafka, and I think he also spoke to the end of things — his years in the civil service in Prague, the end of that civilization after the war, the “modern man” caught in the trap of the industrial revolution, the bureaucracy.

And now? Arthur C. Clarke once said “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” and I think that could apply to the internets but also to the unbelievable powers governments and corporations have to tyrannize us and track us as though by magic.

We have great opportunities, such as this kind of blogging, virtual worldwide communities, but it’s such a fragile set-up.

Me? I’ve turned to the East for my philosophy. Tibetan Buddhism is what I practice, and even that opportunity was caused by the invasion of Tibet by China in the 50s — before that the practice, in a pure oral lineage of teacher to student over a period of 2,500 years, was confined to Tibet.

End of the world? Sure, I think we all feel that. There’s a sense of exhaustion over the forms we have always relied upon, they’ve been stripped away from us in so many ways. So we float in uncertainty — but we also see glimpses of the new, and we carry on. I think young folks already have adapted to this and it’s not unusual at all to them.

Author

But I won’t do that after launch. I take it that it’s better not to, at least as a rule.

partially because I spent all day traveling to, attending, and traveling from a wedding. Today the world began at 8am, and it’ll end when I close my eyes in a little while.

I might add that one of the reasons for the postmodern breakdown of things was actually the end of the world, or the failure of the end of the world (which makes your title nice and fitting). Around the turn of the 19th century, crazy apocalypticism in the West was in full swing, and between the high pitch of pop mysticism and the seeming convergence of all things eschatological, it shouldn’t be a huge surprise that people actively welcomed World War I as the End of Days, the War to End All Wars.

And then something happened: nothing. The war just dragged on, and people died in trenches, and the edifice collapsed. The Great War really was the end of the world, but not of the “real” world. It ended the dominance of 19th century positivism and of the feeling that we could ever make real sense of the world.

Combine that with what was going on in physics at the time, and Western thought starts converging around the impossibility of convergence.

Yikes, I’m really rambling here. Okay, time to wrap up the comment with: Hey, I really enjoyed this diary, but I have nothing intelligent to add.