Throughout the long ages, the proponents of societal reform have traditionally found themselves with the fuzzy end of the lollipop when it came to battling the entrenched Powers That Be’d, at least in terms of military strength. In dozens of eras and in hundreds of contexts, however, those who would change society have learned that the force of numbers is where the power of the people lies, and from this they derived and perfected several ways of exerting considerable (sometimes government-changing) pressure upon the oligarchs, tyrants, and unprincipled politicians of their day.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight your resident historiorantologist will offer for progressive consideration a look at a handful of the means our side has traditionally employed when all appeared lost and the aristocrats were running amok. As we begin, please direct your gaze toward the Eternal City on the Seven Hills, and one of the first successful general strikes…

The tactics of the fights for social justice are nearly as numerous as the contexts under which they have been waged, but there are a few recurring themes that I’ve seen popping up around the left blogosphere lately, and it’s those I’d like to address. I present these only in a vaguely chronological order, with no intention of trying to order, rank, or (necessarily) recommend them.

| Tactic 1: Secessio Plebis Rome; 494 BCE, 449 BCE, 287 BCE A forerunner of the General Strike |

Two thousand years before Marx, the people of ancient Rome fully recognized in whose hands rested the means of production, and they had a fairly good inkling of what would happen if they removed their noses from the Republic’s grindstone. In 495 BCE, a Bushlike patrician named Appius Claudius got himself appointed Consul, and began using the position to tyrannize the lower classes – the plebs – largely by throwing debtors in prison and ordering a levy of troops to support the Fifth war of Rome and Sabines. His blatant Cheneyness, as well as the fact the rest of the legislature was content to hide behind his toga hem while Appius Claudius made all the tough decisions, galvanized the plebs into collective action:

After dismissing the senate, the consuls ascended the tribunal and called out the names of those liable to active service. Not a single man answered to his name. The people, standing round as though in informal assembly, declared that the plebs could no longer be imposed upon, the consuls should not get a single soldier until the promise made in the name of the State was fulfilled. Before arms were put into their hands, every man’s liberty must be restored to him, that they might fight for their country and their fellow-citizens and not for tyrannical masters. The consuls were quite aware of the instructions they had received from the senate, but they were also aware that none of those who had spoken so bravely within the walls of the Senate-house were now present to share the odium which they were incurring. A desperate conflict with the plebs seemed inevitable. Before proceeding to extremities they decided to consult the senate again. Thereupon all the younger senators rushed from their seats, and crowding round the chairs of the consuls, ordered them to resign their office and lay down an authority which they had not the courage to maintain.

Livy, History of Rome

In order to avoid provoking the Senate into knee-jerk resolutions, pleb leaders began meeting in secret; out of this grew a movement that the aristocrats didn’t really know what to do with. Two of the leading pols favored quietly burying the gladius, but…

Appius Claudius, harsh by nature, and now maddened by the hatred of the plebs on the one hand and the praises of the senate on the other, asserted that these riotous gatherings were not the result of misery but of licence, the plebeians were actuated by wantonness more than by anger. This was the mischief which had sprung from the right of appeal, for the consuls could only threaten without the power to execute their threats as long as a criminal was allowed to appeal to his fellow criminals. “Come,” said he, “let us create a dictator from whom there is no appeal, then this madness which is setting everything on fire will soon die down. Let me see any one strike a lictor then, when he knows that his back and even his life are in the sole power of the man whose authority he attacks.”

ibid (emphasis mine – u.m.)

By the following year, the plebs had had enough of Appius Claudius, and to express their displeasure, they packed up their crap and left the city en masse. Tradition (and an ill-fated 20th-century anti-Fascist movement) holds that they vacated to the Aventine Hill, one of Rome’s storied seven hills that had not, at this early date, yet been engulfed by ancient world urban sprawl. From there, they watched as the handful of patricians left in the city came to recognize just how much of their comfortable lifestyle depended on the good graces of their inferiors, and in the end, made several monumental concessions to the plebs in order to get them to come back. Most important of these were the creation of the office of Tribune – a powerful office reserved for plebs which at times had the power to veto acts of consuls, praetors, and even the senate itself – and the much later establishment of the Temple of Concordia, which graced the Forum from the time of the Gracchi onward.

About 50 years later, the plebs were forced to dust off the Secessio tactic, this time to assert their demands for a legal code that was, unlike the one Rome’s priests were currently administering, written down and known to all. Beginning in 462 BCE, the plebs started pushing, and it only took 9 years for the patricians to grudgingly assemble a 10-man commission – the Decemvirate to study the matter. The idea was that they would go to Greece and study how Solon, et. al., were running things, but they likely didn’t venture much further than the Greek city-states in southern Italy.

The plebs were making other demands, too, and while the idea of subjecting themselves to the rule of law struck the Roman patrician class about as favorably as it does Bush’s base, the other rights the lower castes were demanding were the sort of things that could destroy civilization itself, not to mention result in profound ennui, if Livy is to be believed:

He (C. Canuleius, tribune and pleb leader) was advocating the breaking up of the houses, tampering with the auspices, both those of the State and those of individuals, so that nothing would be pure, nothing free from contamination, and in the effacing of all distinctions of rank, no one would know either himself or his kindred. What other result would mixed marriages have except to make unions between patricians and plebeians almost like the promiscuous association of animals? The offspring of such marriages would not know whose blood flowed in his veins, what sacred rites he might perform; half of him patrician, half plebeian, he would not even be in harmony with himself.

The great historioranter continues his harangue against the insolent plebes in a classic blame-the-victim broadside that surely must have a place on Michelle Malkin’s list of Top Ten Ingrate Call-Outs:

Could their ancestors have divined that all their concessions only served to make the plebs more exacting, not more friendly, since their first success only emboldened them to make more and more urgent demands, it was quite certain that they would have gone any lengths in resistance sooner than allow these laws to be forced upon them. Because a concession was once made in the matter of tribunes, it had been made again; there was no end to it. Tribunes of the plebs and the senate could not exist in the same State, either that office or this order (i.e. the nobility) must go. Their insolence and recklessness must be opposed, and better late than never. Were they to be allowed with impunity to stir up our neighbours to war by sowing the seeds of discord and then prevent the State from arming in its defence against those whom they had stirred up, and after all but summoning the enemy not allow armies to be enrolled against the enemy?

but Livy, fair and balanced guy that he was, also included a speech of Canuleius that the tribune gave to the senate after a second secessio had bent the patricians to their will again:

“In a word, does the supreme power belong to you or to the Roman people? Did the expulsion of the kings mean absolute ascendancy for you or equal liberty for all?…Why, have you not on two occasions found out what your threats are worth against a united plebs? Was it, I wonder, in our interest that you abstained from an open conflict, or was it because the stronger party was also the more moderate one that there was no fighting? Nor will there be any conflict now, Quirites; they will always try your courage, they will not test your strength.”

Testing the courage of the patrician class is what secessions and strikes are all about, though the tribune must have been either coy or naïve to assert that violence would never attend a city-vacating work stoppage. Still, the plebs got what they wanted: the Decemvirate promulgated a 10-part legal code in 450 BCE, about which Livy gave some Jeffersonian advice:

“…every citizen should quietly consider each point, then talk it over with his friends, and, finally, bring forward for public discussion any additions or subtractions which seemed desirable.”

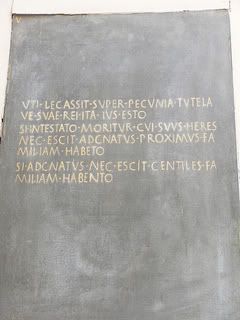

The following year, the code was expanded by two more parts, and the laws of the Twelve Tables – a kind of Bill of Rights, criminal code, and nursery rhymes of torts all rolled into one – were carved into ivory (or maybe brass) and placed on prominent display in the Forum Romanum. The general strike had secured important rights for the plebs once more, but it would take one more secession before patrician families were never again safe from the prospect of losing a son or daughter through matrimony to the ranks of the underclass.

The following year, the code was expanded by two more parts, and the laws of the Twelve Tables – a kind of Bill of Rights, criminal code, and nursery rhymes of torts all rolled into one – were carved into ivory (or maybe brass) and placed on prominent display in the Forum Romanum. The general strike had secured important rights for the plebs once more, but it would take one more secession before patrician families were never again safe from the prospect of losing a son or daughter through matrimony to the ranks of the underclass.

Marriage across class lines wasn’t the only issue in 287 BCE: the plebs were also demanding adoption of the Lex Hortensia, which significantly expanded the political power of the plebs, and, a little later, the Lex Olgulnia, which opened the priesthood to them for the first time. It took yet another (but, as things turned out, the last) secessio, but in the end, the reforms brought about by this final wielding of the power of labor denial were among the most liberating and democratic of all – by giving resolutions of the plebian council the force of law, allowing pleb access to heretofore-inaccessible regions of the social ladder, and allowing for a vast expansion in suffrage, the patricians effectively bargained themselves down to parity with a least some of their perceived inferiors.

Bad ideas die just as tough as the good ones, though, and the oligarchs weren’t about to give up their birthright simply because that’s what they’d publicly sworn an oath to do. Together with nouveau-riche plebs, they would go on to form an anti-pleb social class/political party of their own – the optimates – which basically put a lock on plebian legislative power until the Gracchus Brothers organized the populare party and started exploring how to use voting blocs as political weapons.

Historiorant: A straight-up Secessio Plebis is probably out of the question for us here in the 21st century – such a tactic could only work in a city of a few thousand, and even then, it would rely on a unanimity and commitment to action that only a few of us could muster. Still, dramatic action can bring dramatic gains – which is probably why the secessio (in a slightly altered form) has traveled down to us through the years…

| Tactic 2: General Strike United States; 1877 mixed gains, but workers learned that collective action is necessary in order to win anything at all |

Buhdydharma has suggested that a one-day STRIKE! might wake the Flaccid Caucus from its slumber, though organizing the numbers of participants needed to make a significant impression remains a daunting task. As history shows, and as legitiamte historian gjohnsit, in his outstanding September 9th diary The Great Strike points out, however, “daunting” needn’t necessarily mean “undoable” – especially since there’s often a sense of spontaneity that precludes organization associated with fast-spreading mass-movements.

Back in the Gilded Age, the Halliburtons and Enrons were the railroad companies, which had their way with workers’ rights on an at-whim basis owing to government indifference and an all-around laissez-faire attitude; naturally, Social Darwinism (of the sort recently espoused by Michelle Malkin in her pile-on-the-12-year-old screeds) was the order of the day. It was generally felt by the Republicans of the era (and later ones, too, it turns out) that if you were poor and had to work for a living, then you sucked and you deserved it. So it was that the Pennsylvania Railroad, in the summer of 1877, found itself perfectly within its rights to cut workers’ wages by 10%, while at the same time doubling the number of cars in theirs trains and not adding more crew to serve the expanded workload.

Accepting such concessions in order to protect outrageous CEO bonuses is a 20th/21st century phenomenon; Pennsylvania Railroad Company workers in June, 1877, did not see themselves as subject to that kind of crap. Spontaneously – and, significantly, without the prompting of a union – they walked off the job and began stopping the movement of the company’s precious cargo. They were joined the next month by employees of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which was trying to emulate the Pennsylvania RR’s pay cuts.

At that point, things were getting serious. The governor of West Virginia (home of the B&O strike) called out the militia, but they refused to fire on the striking workers, so he appealed to president Benjamin Harrison. The Republican (natch), in office only a few months, made history by sending federal troops to Martinsburg, where they got the trains moving by showing off their new Gatling guns – though initially, this too was a problem, since Washington had only a small standing army, and most of it was off oppressing Indians on the Plains. Not to fear, though: J.P. Morgan and a few wealthy buddies stepped in and ponied up the pay for some officers, though they drew the line at sharing their wealth with enlisted swine.

By then, however, the strike had spread to other places – and was losing, rather than gaining, focus as momentum took over. Sometime during the middle of the summer of 1877, the strike became less about railroads and more about a pent-up rage of discontent. Street fighting erupted in Maryland and Pennsylvania, and throughout the Rust Best, authorities were paralyzed by rock-hurling mobs of angry citizens. In Baltimore, the militia killed 11 protestors, wounded scores more, and saw about half of their own number quit in disgust at what they were doing as they made their murderous way from their armory to Camden Station.

By then, however, the strike had spread to other places – and was losing, rather than gaining, focus as momentum took over. Sometime during the middle of the summer of 1877, the strike became less about railroads and more about a pent-up rage of discontent. Street fighting erupted in Maryland and Pennsylvania, and throughout the Rust Best, authorities were paralyzed by rock-hurling mobs of angry citizens. In Baltimore, the militia killed 11 protestors, wounded scores more, and saw about half of their own number quit in disgust at what they were doing as they made their murderous way from their armory to Camden Station.

In Pennsylvania, the festivities were kicked off by a single irate flagman named Gus Harris (info via a retelling of Zinn’s People’s History of the United States in 1877: The Great Railroad Strike at Libcom.org). Told he’d have to bend over and take it for the corporate team one more time, Gus refused, which inspired the rest of the train’s crew (he’d been told he’d have to work a “double header” – two engines, twice as many cars, no extra crew) to walk off the job. Soon thousands of people in the union-friendly town were out on the streets.

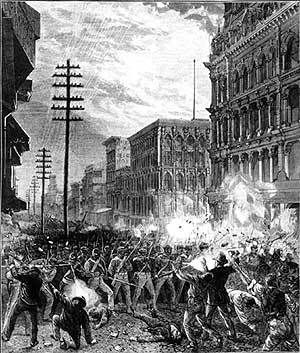

Local authorities, who were having trouble raising up a militia willing to shoot at their own neighbors for having the temerity to demand a little respect, were forced to import goons from Philadelphia. When these militia troops arrived at the Pittsburgh station, they were greeted by a large, mostly-unarmed mob that began pelting them with stones. The militia responded with Blackwater-esque gusto: they started firing volley after volley into the protestor ranks. By the end of the day, the official count of crowd casualties showed 20 dead and 29 wounded (an unusually high ratio for an “accidental” incident), though the real toll was probably higher as relatives and friends likely grabbed up wounded and dead comrades as they fled before the carnage.

In response, the entire city rose up against the occupying militia, and, well…

“Miners and steel workers came pouring in from the outskirts of the city and as night fell the immense crowd proved so menacing to the soldiers that they retreated into the roundhouse.” (Harper’s Weekly)

…where they experienced, according to one militia member/Civil War vet…

“[It was] a night of terror such as last night I never experienced before and hope to God I never will again.” (New York Herald)

quotes via The Great Strike by gjohnsit

They might have all died in the roundhouse that night, had the workers’ plan to crash a flaming oil car into the building not resulted in a near-miss. Realizing that no reinforcements would arrive in time to save them from certain destruction, the Philadelphians were forced to do their own version of the Mogadishu Mile the following morning. They killed 20 and lost 4 of their own as they ran for the fields outside of town, and were still taking sniper fire more than ten miles from the city limit. By then, the mob was torching buildings and railroad cars – in the end, nearly 40 buildings were destroyed, along with more than 100 locomotives and over 1200 rail cars of various sorts.

The same scenes kept playing out, over and over, as the strike entrenched itself in the northeast, then began to make its way west. Reading, Pennsylvania, saw troops kill 10 and wound 40 before being forced to hand their weapons and ammo over to the mob, and in other parts of the state, beleaguered militia forces were obligated to outright surrender to the mobs.

The same scenes kept playing out, over and over, as the strike entrenched itself in the northeast, then began to make its way west. Reading, Pennsylvania, saw troops kill 10 and wound 40 before being forced to hand their weapons and ammo over to the mob, and in other parts of the state, beleaguered militia forces were obligated to outright surrender to the mobs.

Weird Historical Sidenote: First off, could you imagine the punishment a Tweety or a Beck would mete out to Reserve units that surrendered to anti-American commie-pinko Islamofascist hippies? It boggles the mind.

Second, if anyone knows something about why the main railroads being struck against in 1877 were the same ones that wound up on the Monopoly board, please drop a note in the comments – I gotta doubt that it’s a coincidence, and I’d love to know more.

By the end of July, there was significant violence happening in St. Louis and Chicago, and the mayors of both cities were obligated to beg thousands of vigilantes to assist the police in bringing a halt to the rioting and prodding the strikers back to work. When all the bodies were stacked up and all the beans counted, perhaps as many as 200 of the 100-200,000 workers that participated in the Great Strike had lost their lives, with maybe another 1000 arrested. Smoldering railyards around the country were testimony to the millions upon millions of dollars in property damage done by the strikers.

Historiorant: The fact that the Great Strike was a spontaneous outburst, rather than a planned set of job actions, worked against labor in the end. Sure, the companies rescinded their stupid pay cuts, but at the same time, they stepped up anti-organizing measures, virtually ensuring that future conflicts with unions would be every bit as violent as the ones in 1877. Blacklists were created, leaders were jailed, states started modifying their definitions of conspiracy, new National Guard units were created in urban centers – and it took another 25 years before labor found a President willing to side with the working man against the oligarchs.

Labor had discovered the power of its numbers, and just as the UAW has recently and thankfully remembered, striking was shown to be a powerful tool in compelling management concessions. This spirit is perhaps best summed up by a speaker quoted by our own St. Zinn:

“All you have to do, gentlemen, for you have the numbers, is to unite on one idea-that the workingmen shall rule the country. What man makes, belongs to him, and the workingmen made this country.”

| Tactic 3: Boycott Ireland; 1880 solidarity in economic warfare can produce incredible results |

Imagine how big an asshole a person would have to be for their name to actually become a negative word – a non-capitalized noun or verb – in their own language. I can only think of a handful of people who have risen to this level of jerkishness: Vidkun Quisling, the Norwegian Nazi, comes to mind, as does “Go Cheney yourself,” but even these are relatively obscure when compared to the most nefarious of all action-inspirers.

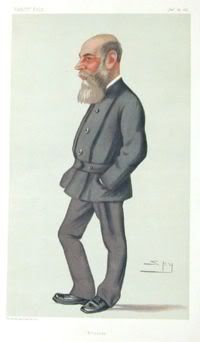

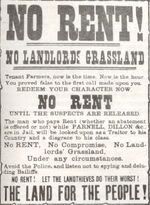

Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott was an agent in for an absentee landlord named John Crichton, the 3rd Lord Earne, at the Lough Mask farm in County Mayo, Ireland, in 1880. Loughmask was a decent-sized spread, with perhaps 300 sheep and 50 head of cattle, and it required a large number of laborers to do all the tasks that needed to be done as the harvest season approached. Unfortunately for him, the Irish Land League had chosen that particular season to advance its “3 F’s” program, which sought Fair rent, Fixity of tenure and Free sale of land as means of making life a bit more equitable (and survivable) for tenant farmers. When Boycott spurned the League’s demand that he reduce the rents they were paying on the land he was managing, the peasants recalled the words of Charles Stewart Parnell in his famed Ennis speech:

Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott was an agent in for an absentee landlord named John Crichton, the 3rd Lord Earne, at the Lough Mask farm in County Mayo, Ireland, in 1880. Loughmask was a decent-sized spread, with perhaps 300 sheep and 50 head of cattle, and it required a large number of laborers to do all the tasks that needed to be done as the harvest season approached. Unfortunately for him, the Irish Land League had chosen that particular season to advance its “3 F’s” program, which sought Fair rent, Fixity of tenure and Free sale of land as means of making life a bit more equitable (and survivable) for tenant farmers. When Boycott spurned the League’s demand that he reduce the rents they were paying on the land he was managing, the peasants recalled the words of Charles Stewart Parnell in his famed Ennis speech:

When a man takes a farm from which another had been evicted you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him, you must shun him in the streets of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fair green and in the marketplace, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in a moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of his country as if he were the leper of old, you must show your detestation of the crime he has committed.

This kind of ostracism might’ve been a new way of engaging in economic warfare, but the underlying concept was both easy to identify and simple to implement – so long as one’s neighbors were also on-board. In the case of the unfortunate Captain Boycott, the people of County Mayo were more or less unified against him, and he was forced to watch impotently as his work force drifted away – even the postman refused to deliver his mail. Boycott sought desperately to hire laborers to harvest his crops, but there were no takers in the area scabby enough to try to cross a picket line of angry, hungry Irish peasants.

News of Boycott’s predicament spread quickly through the British Isles, and even as newspapers in London, Belfast, and Dublin were starting use the man’s name as a verb, a 50-strong “relief force” of England-sympathizing Orangemen from the northern counties assembled to help him get his crops in. Escorting and protecting the scabs on their march through Ireland were about 1000 soldiers and police of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. In the end, the British government is estimated to have spent around £10,000 in order to bring in a harvest of around £350 worth of potatoes.

News of Boycott’s predicament spread quickly through the British Isles, and even as newspapers in London, Belfast, and Dublin were starting use the man’s name as a verb, a 50-strong “relief force” of England-sympathizing Orangemen from the northern counties assembled to help him get his crops in. Escorting and protecting the scabs on their march through Ireland were about 1000 soldiers and police of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. In the end, the British government is estimated to have spent around £10,000 in order to bring in a harvest of around £350 worth of potatoes.

And Captain Boycott? Dejected and defeated, he left Ireland with his family on December 1st, returning to a London whose papers were already using his name to connote organized ostracism. Though the linking of the name with the action is generally attributed to a priest in County Mayo, credit for the verb form of Boycott’s name probably goes to The Times of London, which on November 20 (while the Orangemen were still harvesting the taters) reported, “The people of New Pallas have resolved to ‘boycott’ them and refused to supply them with food or drink.” The Captain’s legacy was sealed by January of the following year, when The Spectator noted “Dame Nature arose….She ‘Boycotted’ London from Kew to Mile End.”

The boycott has since been used by reformers in many different guises, with a wide range of effect. This is largely based on the ability of the boycotters to bring an actual sense of ostracism to the entity being boycotted – fail to make the bad guy feel isolated, and even the most nobly-inspired boycott will fizzle. Here are a few successful ones…

- Stamp Act protests – late 1760s. Technically not a boycott because it preceded the naming events, colonists were nevertheless unified in their telling of the King to take his stamps and shove them.

- Swadeshi movement – December, 1921. Organized by Gandhi, this self-reliance offensive also urged the pure of (Indian) heart to reject British titles, honors, and jobs.

- Montgomery Bus Boycott – December, 1955. A successful year-long boycott (with all the attendant ride-sharing, walking, and other hassles) against racist seating laws sets in motion the modern Civil Rights movement.

- United Farm Workers grape boycott – late 1960’s. Caesar Chavez wins collective bargaining rights for farm laborers by putting squeeze on the grape industry.

…the striking thing about which is the tremendous amount of grassroots support each received. They also show that a successful boycott is a targeted boycott – and once the enemy has been designated, then nothing less than complete and faithful adherence to their principles will see the boycotters through to victory.

Historiorant:

I could go on about the different types of boycotts (and of strikes) for a while, but time is again running short (ain’t it always?), and there’s still a few illustrations to insert before posting. A diary yet to be written will have to address some of the other means of exerting the public will upon recalcitrant pols and lords of industry – if nothing else, the idea of protest marches, both dangerously spontaneous and the very well-organized deserves a fist-waving shout-out. Until then, though, you can count me as favoring the secessio plebis as the course we ought to be taking – y’all can hole up here at the Cave until Bushco gives in and allows for the restoration of the rule of law.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, and DocuDharma.

11 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

so what can history do to inform our next steps?

Many thanks for another delightful lesson!

Excellent. Thanks.

That deserves a moon, Moonbat! I shot this during a recent lunar eclipse and a few dark clouds were passing by – perfect evening for Moonbats! (I felt right at home!)

“Testing the courage of the patrician class is what secessions and strikes are all about”