Hey, it happens. History is replete with stories where the good guys don’t win in the end, where horrific acts go unavenged and unpunished, where leaders of nations descend into madness, dragging their countrymen down with them. At many various times and in many various places, peoples have found themselves saddled with rule by psychopaths, paranoids, and delusional megalomaniacs of all stripes – and simply being alive now, in the “modern” age, is no guarantee that it can’t, won’t, or hasn’t happened again.

Far be it from me to try to psychoanalyze any contemporary political figures, but it recently occurred to your resident historiorantologist that, given the proverbial insanity of American policymaking over the past few years, a look at a couple of the less-balanced monarchs who have walked the tightrope of power in the past might be in order. Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight the tortuous paths of logic will take us from Rome to a fairy-tale castle in the Bavarian Alps…with absolutely no implied connection to anything happening in Washington today.

Historiorant: It is notoriously difficult to judge their mental status of historical figures – I know precious little about what drives the students in my classroom, to say nothing of what might have motivated a man deceased lo, these 2000 years, and who commanded the fates of men and nations while he was alive. Furthermore, readers ought to be aware that I have received no training in head-shrinking beyond a couple of undergrad Psych courses, so any diagnoses of mine ought to be taken with a few milligrams of lithium.

Classically Insane

The City of Eternal Metaphors comes through once again in the area of leaders who have lost their minds – from simple outlandishness to matricide to incredibly decadent decadence, more than a handful of Rome’s emperors set a standard for ruling without the benefit of one’s faculties that has rarely been approached in the centuries since. Indeed, some of their names have become synonymous with madness, and though your resident hisotriorantologist won’t have enough time to look into Nero on this particular evening, no story of crazed kings would be complete without checking in on Caligula.

Still, even as we prepare to delve into a case study or two, we have to remember that mental illness is a serious issue – the idea behind this diary is to expose some of the dangers of allowing a person with an untreated disorder to continue in a role of power and authority over a government, not to mock those who suffer from these conditions. Imho, if anyone deserves our historical derision, it would be those who were in positions to alleviate the suffering of their people, and went-along-to-get-along with the situation nonetheless. In virtually every case of a leader suffering from mental illness, the backstory is complicated and sad enough to elicit some sympathy – or at least a realization that the circumstances endured by “mad” kings and queens could make them out to be tragic, rather than comic or melodramatic, figures.

Case 1: Emperor Gaius (Caligula), r. 37-41 CE

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, whom must of us would better recognize by his nickname, Caligula, is typical of the kind of conundrum of historiography mentioned above. As a precocious little kid, he was beloved by the legionaries of the army with which he and his mother, Agrippina, traveled, and when his mother had a little army uniform made for the tot and he appeared before the troops wearing a miniature pair of the legionary’s footwear – the caliga – Gaius was forever monikered with the diminutive form of the noun.

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, whom must of us would better recognize by his nickname, Caligula, is typical of the kind of conundrum of historiography mentioned above. As a precocious little kid, he was beloved by the legionaries of the army with which he and his mother, Agrippina, traveled, and when his mother had a little army uniform made for the tot and he appeared before the troops wearing a miniature pair of the legionary’s footwear – the caliga – Gaius was forever monikered with the diminutive form of the noun.

This army happened to belong to Germanicus Julius Caesar, Gaius’ father and adoptive son of Caesar Augustus (r. 31 BCE-14 CE), and Agrippina and Gaius traveled with it for their own safety. Emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37) had named Germanicus heir to the imperial throne over the objections of his own natural-born family, and in the poisonous (literally) snake pit that was Roman politics during the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, jockeying for position in the line succession was a serious contact sport.

In the end, traveling with an army didn’t do Germanicus much good: he died under mysterious circumstances while on a military campaign in Syria when Gaius was seven. From there, relations between his mother and the Emperor, who was also his great-uncle, rapidly fell apart (Agrippina was the granddaughter of Augustus, so her choice of a replacement husband had important ramifications for Tiberius’ scheming), and Agrippina found herself first demoted, then exiled. Gaius eventually wound up living at Tiberius’ palace of twisted carnality on the island of Capri.

This all gets a little too NAMBLA for my sensibilities, so I’ll let Suetonius (via the Robert Graves translation) describe the sort of environment in which the 19-year-old future emperor found himself:

After retiring to Capri, where he (Tiberius) had a private pleasure palace built, many young men and women trained in sexual practices were brought there for his pleasure, and would have sex in groups in front of him. Some rooms were furnished with pornography and sex manuals from Egypt – which let the people there know what was expected of them. Tiberius also created lechery nooks in the woods and had girls and boys dressed as nymphs and Pans prostitute themselves in the open. The place was known popularly as “goat-pri”.

Some of the things he did are hard to believe. He had little boys trained as “minnows” to chase him when he went swimming and to get between his legs and nibble him. He also had babies not weaned from their mother’s breast suck at his chest and groin. There was a painting left to him, with the provision that if he did not like it he could have 10,000 gold pieces, and Tiberius kept the picture. It showed Atalanta sucking off Meleager. Once, in a frenzy while sacrificing, he was attracted to the acolyte and could not wait to hurry the acolyte and his brother out of the temple and assault them. When they protested, he had their legs broken.

The Tiberius stories could go on and on, but you get the idea; by the time Gaius ascended the throne after the old pervert’s death in March, 37 CE, he had had no more political training than an honorary quaestorship, and was utterly unprepared for the power and responsibility he was almost instinctively gathering around himself. Tiberius’ will made him only co-emperor along with the old emperor’s grandson, so Gaius had Tiberius declared retroactively insane (thus making the will null and void), and a little later simply had his rival assassinated by loyalists among his Blackwater Praetorian Guard. He entered the city to wild rejoicing, won further loyalty when he shrewdly awarded the first bonus in the empire’s history to the Praetorian Guard, and probably eased the mind of many a worried patrician when he publicly burned Tiberius’ papers.

Power tends to corrupt…

No one really knows what triggered the fall from this promising start, though theories abound. In the first few months of his reign, he staged popular gladiatorial games (mostly in the amphitheatre of Taurus; the Colloseum had not yet been constructed), gave tax breaks, and, if Suetonius is to be believed, was the cause of over 160,000 animals being slaughtered in celebration of the fact that he wasn’t Tiberius. In October, however, he fell ill, and things were never quite the same afterwards.

This is also the point at which it becomes difficult to judge whether or not Caligula was actually, certifiably insane. Those historioranters who wrote about him – Suetonius, Philo of Alexandria, Josephus, and Seneca, and a handful of others – were members of the upper castes of society (i.e., the insults Gaius hurled at the Senate and the Patrician class reflected on they and their families), were almost uniformly opposed to Caligula’s rule, and used their quills the same way Faux News uses a TelePromTer. Additionally, only a couple of surviving works were contemporary with Caligula’s rule – the most oft-cited sources, those of the Patricians Suetonius and Cassius Dio, were written 80 and 180 years (respectively) after the Gaius’ reign.

This is also the point at which it becomes difficult to judge whether or not Caligula was actually, certifiably insane. Those historioranters who wrote about him – Suetonius, Philo of Alexandria, Josephus, and Seneca, and a handful of others – were members of the upper castes of society (i.e., the insults Gaius hurled at the Senate and the Patrician class reflected on they and their families), were almost uniformly opposed to Caligula’s rule, and used their quills the same way Faux News uses a TelePromTer. Additionally, only a couple of surviving works were contemporary with Caligula’s rule – the most oft-cited sources, those of the Patricians Suetonius and Cassius Dio, were written 80 and 180 years (respectively) after the Gaius’ reign.

Those guys didn’t use the same terms as we do to define illness, either – Juvenal claims the insanity was the result of a magic potion, while Suetonius says Gaius suffered from “falling sickness” (possibly epilepsy) when he was young. Regardless of the possible root causes, however, Caligula’s recovery from his illness did not bode well for his family or his especially loyal supporters: shortly after he was up and about again, he obligated several people who had vowed to exchange their lives for his recovery to make good on their promises. He also banished his wife and his father-in-law, presumably so he could spend more time with his younger sister Drusilla, with whom he had a creepily close relationship.

The following year Caligula continued with public reforms, even as his private life got weirder and weirder. Among other things, he provided aid to victims of fires, abolished some taxes, and allowed for an expansion of the pool of potential officeholders. He also approved and initiated some large-scale building projects, including revamping the walls of Syracuse and surveying the Isthmus of Corinth for a planned canal, and set plot devices for future Dan Brown novels into motion when he brought the Egyptian Obelisk to Rome (though it wasn’t moved to its present site in St. Peter’s Square until much, much later). Most significantly, he restored democratic elections, which did not sit well with the Patricians, who felt that Caligula’s actions,

The following year Caligula continued with public reforms, even as his private life got weirder and weirder. Among other things, he provided aid to victims of fires, abolished some taxes, and allowed for an expansion of the pool of potential officeholders. He also approved and initiated some large-scale building projects, including revamping the walls of Syracuse and surveying the Isthmus of Corinth for a planned canal, and set plot devices for future Dan Brown novels into motion when he brought the Egyptian Obelisk to Rome (though it wasn’t moved to its present site in St. Peter’s Square until much, much later). Most significantly, he restored democratic elections, which did not sit well with the Patricians, who felt that Caligula’s actions,

though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many, and the funds on hand should be exhausted and private sources of income fail, many disasters would result.

Presumably, the rabble was unaware of some of the more egregious money-wasting schemes upon which the Emperor embarked:

In reckless extravagance he outdid the prodigals of all times in ingenuity, inventing a new sort of baths and unnatural varieties of food and feasts; for he would bathe in hot or cold perfumed oils, drink pearls of great price dissolved in vinegar, and set before his guests loaves and meats of gold, declaring that a man ought either to be frugal or Caesar. He even scattered large sums of money among the commons from the roof of the basilica Julia for several days in succession.

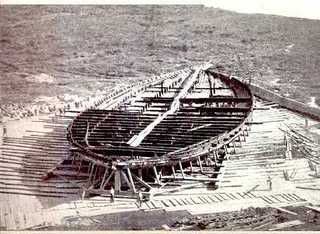

(on Lake Nemi, near Rome) He also built Liburnian galleys with ten banks of oars, with sterns set with gems, particoloured sails, huge spacious baths, colonnades, and banquet-halls, and even a great variety of vines and fruit trees; that on board of them he might recline at table from an early hour, and coast along the shores of Campania amid songs and choruses. He built villas and country houses with utter disregard of expense, caring for nothing so much as to do what men said was impossible. So he built moles out into the deep and stormy sea, tunneled rocks of hardest flint, built up plains to the height of mountains and razed mountains to the level of the plain; all with incredible dispatch, since the penalty for delay was death. To make a long story short, vast sums of money, including the 2,700,000,000 sesterces which Tiberius Caesar had amassed, were squandered by him in less than the revolution of a year.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Those boats, by the way, were among the largest ever constructed in the ancient world, and were meant to evoke the memory of the barges of the Pharaohs of Egypt. Benito Mussolini had the lake in which their hulls rested drained in 1927, and the vessels underwent study and reconditioning until they were largely destroyed during the German retreat from Rome in 1944.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Those boats, by the way, were among the largest ever constructed in the ancient world, and were meant to evoke the memory of the barges of the Pharaohs of Egypt. Benito Mussolini had the lake in which their hulls rested drained in 1927, and the vessels underwent study and reconditioning until they were largely destroyed during the German retreat from Rome in 1944.

The bills for all the tax breaks and extravagance started coming due the next year, and it turned out that Caligula’s economic policies had been about as well thought-out as those of George W. Bush. Since the treasury was virtually exhausted, Caligula turned to trumped-up charges, trials, and occasionally executions as justification for the seizure of wealthy estates. When that didn’t generate enough revenue, he took to auctioning the lives of gladiators at the arena, asking for public loans to replenish the state’s treasury, and accusing current and former government officials of embezzlement.

And You Thought a Codpiece-Wearing, Fake Carrier Landing was Absurd?

By this point (39 CE), Caligula was coming apart. Recalling that a soothsayer had once told him that he had “no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae,” Caligula rose to the challenge by gathering just about every seagoing vessel he could find and having his engineers rope them together into a pontoon bridge, a la Xerxes at the Hellespont three centuries earlier. Wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great (which he’d had removed from the conqueror’s sarcophagus), he then rode his favorite horse, Incitatus, across the Bay, and in the process delayed grain shipments that would have gone a long way toward averting the famine that befell the Empire later that year.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Incitatus actually had a pretty successful political career, especially given that he was, quite literally, an animal:

One of the horses, which he named Incitatus, he used to invite to dinner, where he would offer him golden barley and drink his health in wine from golden goblets; he swore by the animal’s life and fortune and even promised to appoint him consul, a promise that he would certainly have carried out if he had lived longer.

Caligula was also a military leader of our President’s own caliber – see if you don’t find any similarities in this passage by Suetonius:

He had but one experience with military affairs or war, and then on a sudden impulse…was seized with the idea of an expedition to Germany. So without delay he assembled legions and auxiliaries from all quarters, holding levies everywhere with the utmost strictness, and collecting provisions of every kind on an unheard of scale. Then he began his march and made it now so hurriedly and rapidly, that the praetorian cohorts were forced, contrary to all precedent, to lay their standards on the pack-animals and thus to follow him; again he was so lazy and luxurious that he was carried in a litter by eight bearers, requiring the inhabitants of the towns through which he passed to sweep the roads for him and sprinkle them to lay the dust.

On reaching his camp, to show his vigilance and strictness as a commander, he dismissed in disgrace the generals who were late in bringing in the auxiliaries from various places, and in reviewing his troops he deprived many of the chief centurions who were well on in years of their rank, in some cases only a few days before they would have served their time, giving as a reason their age and infirmity; then railing at the rest for their avarice, he reduced the rewards given on completion of full military service to six thousand sesterces.

And, also like the Decider, Caligula seems to have had a penchant for making himself out to be a far more able commander than he actually was – here he is at the shores of the English Channel, at the end of a disastrous military adventure:

Finally, as if he intended to bring the war to an end, he drew up a line of battle on the shore of the Ocean, arranging his ballistas and other artillery; and when no one knew or could imagine what he was going to do, he suddenly bade them gather shells and fill their helmets and the folds of their gowns, calling them “spoils from the Ocean, due to the Capitol and Palatine.” As a monument of his victory he erected a lofty tower, from which lights were to shine at night to guide the course of ships, as from the Pharos. Then promising the soldiers a gratuity of a hundred denarii each, as if he had shown unprecedented liberality, he said, “Go your way happy; go your way rich.”

Finally, there was the whole god-complex thing. Over time, Caligula became more and more certain that he was, in fact, a living deity, and he began setting policy to that effect. He obligated the citizens of Rome (including the Senators) to worship his physical being; began appearing in public dressed as Herakles, Apollo, and, Guiliani-like, Venus; and even demanded the construction of a statue of himself inside the Temple of Jerusalem. Knowing his rebellion-prone subjects better than the Emperor, the Roman governor of Syria delayed building this particular blasphemy for almost a year before Caligula, under pressure from clearer-thinking advisors, rescinded the order.

When the Coverage on One’s Pre-existing Condition Runs Out

The insults Caligula hurled at the Senate – one of my favorites is his obligating Senators to jog beside his chariot – resulted in several attempts on his life, and culminated with his assassination on January 24, 41 CE. This was a thoroughly Caesar-like affair: while Caligula was addressing a troupe of actors, he was approached by a group of Senators, among which was a praetorian tribune whom he had publicly derided as effeminate and a “Venus.” Details get sketchy here – the sources vary on whether the next sequence of events occurred in public or in a corridor of the imperial residence – but what is certain is that the tribune, Cassius Charea, was among the first to sink a blade into Caligula, and before it was all finished, Caligula had been perforated by about 30 knife- and sword-wounds. He was 28.

One of the arguments against Caligula’s being insane is the cagey way with which he interacted with his Praetorian Guard and other elite units that he kept close to him. Like the Commander Guy, who has spent six years feathering the nests of Erick Prince and other wealthy warmongers, Caligula had paid particular attention to staying on the good side of violent and purchasable warriors – and now his Germanic Guard went on a rampage to avenge him. In the confusion, the Praetorian Guard managed to slip Caligula’s uncle Claudius out of the city and into the safety of one of their camps.

In the meantime, what was left of the Senate (after Tiberius’ various treason trials and Gaius’ political purges) tried to restore the Republic, but found it could not count on the support of the military. Despite their leader’s complicity in the plot against Gaius, Praetorian loyalties remained affixed to the office of the emperor, not to the people or the nation-state, so the assassins had to content themselves with stabbing Gaius’ wife to death, then dashing out his baby daughter’s brains against a wall. These and other rather heavy-handed actions turned the populace against the Senate, and they began to call that justice be done upon the murderers of Gaius and his family. It was in this environment that Claudius made his own play for power: having secured the support of the Praetorians, he now paved the way for his own coronation by pronouncing death sentences upon Cassius Charea and his cohorts.

The period after the assassination of Gaius might have been the Senate’s best chance to restore the Republic, but their efforts failed – Rome would go on to prosper and to suffer under four centuries’ worth of emperors good and bad. The reign of Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) is something of a mixed bag – he conquered most of Britannia, built aqueducts and other public works, and revitalized the governmental and judicial systems, but he also had to contend with serious conniving being done behind his back. Eventually, this conspiring would kill him: he died on October 13, 54 CE, most likely as a result of eating poisoned mushrooms.

And what can we say of Claudius’ successor, Nero, except that he deserves a set-the-record-straight diary on mental illness of his own? Perhaps someday I’ll try’n write one up, but for now (and since this piece is really about Gaius), I’ll leave the gentle reader with some concluding remarks about Caligula from Garrett G. Fagan of Pennsylvania State University:

He appears, once in power, to have realized the boundless scope of his authority and acted accordingly. For the elite, this situation proved intolerable and ensured the blackening of Caligula’s name in the historical record they would dictate. The sensational and hostile nature of that record, however, should in no way trivialize Gaius’s importance. His reign highlighted an inherent weakness in the Augustan Principate, now openly revealed for what it was — a raw monarchy in which only the self-discipline of the incumbent acted as a restraint on his behavior.

Caligula? Somebody we know? Naw…

And Now for Something Completely Different

Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm II might have been born in an entirely different age and time as Gaius Caesar, but he could certainly relate to the Roman’s miserable childhood, for he had had one of his own. Born in 1845, the son of Crown Prince Maximillian II and Marie of Prussia was never spared the rod as his tutors reminded him that he would someday be a mid-19th century King of Bavaria himself – the odd mixture of fawning indulgence and stern, Teutonic discipline that defined his youth would have been enough to mess anybody up. With his parents indifferent and aloof, Ludwig gravitated toward his maternal grandfather, King Ludwig I (r. 1825-1848; had abdicated in favor of his son during the Revolutions of 1848), and slowly drifted off into a fantasy world of his own making.

Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm II might have been born in an entirely different age and time as Gaius Caesar, but he could certainly relate to the Roman’s miserable childhood, for he had had one of his own. Born in 1845, the son of Crown Prince Maximillian II and Marie of Prussia was never spared the rod as his tutors reminded him that he would someday be a mid-19th century King of Bavaria himself – the odd mixture of fawning indulgence and stern, Teutonic discipline that defined his youth would have been enough to mess anybody up. With his parents indifferent and aloof, Ludwig gravitated toward his maternal grandfather, King Ludwig I (r. 1825-1848; had abdicated in favor of his son during the Revolutions of 1848), and slowly drifted off into a fantasy world of his own making.

Well, maybe not entirely of his own making; he had help. King Max II had built the family’s castle of Hohenschwangau back in the 1830s, and young Ludwig loved hanging out amidst the impressive collection of Romantic art portraying highly idealized versions of Germanic myths and legends. Perhaps his favorite imagery centered around swans, but he also developed a lifelong love for that region in the Bavarian Alps; once he became king, he much preferred the solitude of Alpine lakesides to the politickin’ and preznittin’ he would’ve been expected to do back in Munich.

Well, maybe not entirely of his own making; he had help. King Max II had built the family’s castle of Hohenschwangau back in the 1830s, and young Ludwig loved hanging out amidst the impressive collection of Romantic art portraying highly idealized versions of Germanic myths and legends. Perhaps his favorite imagery centered around swans, but he also developed a lifelong love for that region in the Bavarian Alps; once he became king, he much preferred the solitude of Alpine lakesides to the politickin’ and preznittin’ he would’ve been expected to do back in Munich.

(larger image showing Hohenschwangau setting (taken from Schloss Neuschwanstein) here)

In 1858, Ludwig first got turned on to Richard Wagner, when his governess told him about a planned production of Lohengrin, an opera about the German Swan-Knight. Though he read the librettos for both Lohengrin and Tannhauser, and devoured tidbits of gossip about Wagner like a schoolgirl reading Teen Beat, it wasn’t until February 2, 1861, that Ludwig finally got to see an actual performance. So it was that while the Confederate States of America were organizing themselves in Montgomery, Alabama, the Crown Prince of Bavaria was finding the production of Lohengrin that he was watching everything he’d hoped for, and more.

That we in the 21st century have ever heard of Richard Wagner – and let’s face it: Apocalypse Now would have been a different film without “Ride of the Valkyries” – is due largely to the good graces (and wide-open purse) of King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Wagner was constantly in trouble with creditors, and though their relationship occasionally grew stormy, Ludwig often stepped in with an infusion of cash or a lakeside cabin in the Alps just when Wagner needed it most. When, in 1863, Wagner whined publicly that the German arts were in a miserable state, and only salvation by a prince would allow him to realize his vision of the heights to which those arts could aspire, Ludwig promised to be that prince. The next year, after he’d ascended to the throne at the age of 18 (due to his father’s untimely death), Ludwig set out to make good on his vow.

That we in the 21st century have ever heard of Richard Wagner – and let’s face it: Apocalypse Now would have been a different film without “Ride of the Valkyries” – is due largely to the good graces (and wide-open purse) of King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Wagner was constantly in trouble with creditors, and though their relationship occasionally grew stormy, Ludwig often stepped in with an infusion of cash or a lakeside cabin in the Alps just when Wagner needed it most. When, in 1863, Wagner whined publicly that the German arts were in a miserable state, and only salvation by a prince would allow him to realize his vision of the heights to which those arts could aspire, Ludwig promised to be that prince. The next year, after he’d ascended to the throne at the age of 18 (due to his father’s untimely death), Ludwig set out to make good on his vow.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Ludwig credited himself for Wagner’s career; upon hearing of the composer’s death in 1883, the King is supposed to have said,

“It was I who was the first to recognise the artist whom the whole world mourns; and it was I who saved him for the world!”

Ludwig got behind productions of the “unproducable” Tristan und Isolde, and later helped to construct the Bayreuth Festival Theater so that Wagner’s four-night, twenty-hour epic Der Ring des Nibelungen (from whence comes “Valkyries”) could be performed in an appropriate venue. He even contemplated abdicating and joining his friend in Switzerland when Wagner’s uncouth ways got him banished from Munich, but the composer – recognizing that the King without his throne was little more than what modern-day Trekkers call a “fanboy” – talked him out of such rash action. Still, the obsession with all things Nordic/Romantic, Wagnerian, and swan-related never did go away: In the insanity trial that immediately preceded his suspicious death, Ludwig’s servants were deposed on his habit of wearing a Lohengrin costume in the middle of the night.

When Reality Intrudes on the Dream

Just after Munich’s high society obliged him to banish his buddy, affairs of love and war imposed themselves upon the young king. In 1866, owing to long-running family allegiances, he joined Bavaria with Austria in the Seven Weeks’ War against the Prussians. His side lost, with the main impact for his country being that its army was placed at the disposal of the Prussian general staff, should they someday need it. Turns out they did, and only a few years later: When Otto von Bismarck orchestrated a war against France in 1870, Bavaria’s troops were some of those summoned to the Prussian banner as part of an overarching (and ultimately successful) strategy to unite Germany, but from Ludwig’s perspective, it represented one more example of Freistadt Bayern‘s loss of sovereignty under his rule.

The alliance in the war with Prussia brought Ludwig into contact with Sophie, the younger sister of the Empress of Austria. Since the girl was also a huge Wagner-head, the couple got along famously, and in January, 1867, Ludwig was maneuvered by Sophie’s mother into publicly announcing their intention to marry. Even as his happy nation feted the couple, his moroseness grew: as the year dragged on, he kept postponing the wedding and doing other things – like sitting in separate opera boxes – that made people wonder what was up. To his friends, it was pretty clear; in a letter to Wagner he wrote:

“Oh, if only I could be carried on a magic carpet to you . . . at dear, peaceful Tribschen* – even for an hour or two. What I would give to be able to do that!”

*Wagner’s house in Lucerne, Switzerland.

Sophie tried to let the miserable young king off the hook, but he only delayed the wedding for another month – it was her father who finally stepped in and ended the sordid non-affair. She went on to marry a French nobleman (she died in a horrible fire at the Paris Charity Bazaar in 1897), and Ludwig…well, let’s just say he remained a bachelor.

On second hand, let’s not, since it was his struggles with his own sexuality that both defined Ludwig II and led him to the depths of self-loathing torment. The fact that he was gay did not square with his strict Catholic upbringing; this is evidenced by the torment in his private diaries (originals destroyed in WWII, but copies of some pages survive):

I lie in the sign of the Cross……..,in the sign of the sun….. and of the moon (orient! rebirth through Oberon’s magic horn-). May I and my ideals be accused if I should fall once more. Thank God this cannot happen again, for God’s holy will and the King’s august word shall protect me. Only spiritual love is allowed; sensual love is accursed! I call down a solemn anathema upon it…….

***

Not again in January, nor in February! The important thing is as far as is possible to get out of the habit of it – with God and the king’s help!

No more pointless cold baths……….. 11 January 1870.

***

Solemn oath taken before the picture of the Great King; “To abstain from every kind of stimulation for 3 months”. “Forbidden to approach closer than 1 1/2 paces.” …………… 29 June 1871.

Ludwig had many affairs with strapping young army officers, but he also enjoyed a longer-lasting (like, 20-years) relationship with his equerry, Richard Hornig. To this day, though, guides at the castles he built are loathe to tell the tourists why it was that Ludwig never sired a child – which gives some indication of how repressed the whole issue was in a conservative land like Bavaria in the late 19th century. Given that he was also being bullied by no less than Otto von Bismarck on a regular basis, one can almost empathize with the way Ludwig retreated into a dreamworld.

der Märchenkönig

He got started on building that dreamworld right away: in 1869, construction began on Vorderhohenschwangau (“Further Hohenschwangau”), which – even if not entirely finished – is one of the most beautifully recognizable castles in the world. Renamed Neuschwanstein (“New Swan Rock”) shortly after Ludwig’s death in 1886, it is one of the most photographed buildings in all of Europe, and served as the inspiration for Walt Disney’s Magic Kingdom castle:

Ludwig’s second castle was an expansion – a vast expansion – of his father’s hunting lodge at Linderhof, not too far from Hohenschwangau and Neuschwanstein. Work began in 1874, and by 1880, the rococo-infused palace had become Ludwig’s favorite. He especially liked visiting the various themed Pavilions (like the Moroccan Kiosk and the Indian Pavilion) scattered about the grounds.

Ludwig’s final castle (though there was one more, Schloss Falkenstein, on the drawing boards) was the most flamboyant yet: a replica of Versailles called Herrenchiemsee. Constructed as an homage to Absolutism, the King of Bavaria only got to spend a total of about a fortnight there before he was called away from Linderhof to face his inquisitors in Munich. (here’s a link if you’re interested in How much did Ludwig’s Castles cost to build?)

Ludwig despised affairs of state and refused to meet with his ministers, who, by 1885, were getting a little worried about the amount of money the King was running through. There were rumors that Ludwig was asking everyone from the Duke of Westminster to the Shah of Iran for money, and Ludwig’s cabinet ministers felt justified in arranging for a constitutional coup that would replace the “Mad King.” They brought Ludwig’s aged uncle, Luitpold, into the loop, but he wanted no part of the throne unless it could be unequivocally proven that Ludwig was actually, certifiably insane. Accordingly, the conspirators brought in some hired-gun psychiatrists, and found a disgruntled employee to dig up dirt from the king’s staff (and from longtime lover Richard Hornig, who had turned on the king). Here are just a few salacious details from the report:

Insanity ran in his family. Prince Otto, Ludwig’s younger brother, had been diagnosed insane for years and committed to an asylum since he was a young man.

He suffered from strange and sick fantasies. Once he told Hornig that he wished to smash a jug over the Queen-mother’s head, drag her around by her hair, and stamp on her breasts with his heels. He also told him that he had dreamed of pulling King Max (his father) out of his coffin and bash his ears.

Towards the end, the King was obsessed with Absolute Monarchy. Army officers were ordered to set up Absolute Rule in Bavaria. Servants were made to bow low and grovel in the King’s presence. He even sent servants on missions to find a country whose government was by Absolute Rule and negotiate a trade with him, ie. swap Bavaria for this country.

Railroad to Bedlam

The committee assigned to study Ludwig’s mental health wrote him a brutal letter describing their “findings:”

“Your Majesty is in a very advanced stage of mental disorder, a form of insanity known to brain-specialists by the name ‘Paranoia’. As this form of brain-trouble has a slow but progressive development of many years duration, Your Majesty must be regarded as incurable, a still further decline of the mental powers being the natural development of this disease. Suffering from such a disorder, freedom of action can no longer be allowed and Your Majesty is declared incapable of ruling, which incapacity will be not only for a year’s duration, but for the length of Your Majesty’s life.”

and Empress Elizabeth of Austria thought she smelled Ralph Naccio-style rat:

“The King was not mad; he was just an eccentric living in a world of dreams. They might have treated him more gently, and thus perhaps spared him so terrible an end.”

but in a fast-moving series of events in June, 1886, the King was cornered, arrested, and moved to Schloss Berg, near Munich. At 11:30 PM on the 13th, only two days after his house arrest had begun, Ludwig’s body was found floating alongside that of Professor Gudden (one of the psychiatrists who’d diagnosed Ludwig without ever meeting him) in Lake Starnberg. Some of the strangeness here includes the fact that Ludwig had tried to call for an insurrection on his behalf (the newspapers in which the cry would have appeared were suppressed before distribution), and that even though his death was ruled a suicide by drowning, no water was found in the king’s lungs (it might also be mentioned that he, unlike Caligula, was a strong swimmer).

Bavaria’s days as an independent state were already numbered when Luitpold assumed the regency for Ludwig’s brother Otto. The poor prince really did suffer from mental illness, and had been confined under close medical supervision since 1875 – there’s a good chance he was never even aware he had been made king. Otto was eventually deposed by Luitpold in favor of the latter’s son, Ludwig III, who reigned from 1913 to the end of the Bavarian kingdom on November 7, 1918.

Ironically, Ludwig II’s spending on architects and art did far more for Bavaria in the long run than anything accomplished by those who accused him of squandering state resources (he wasn’t – he was spending his allowance on castle-building, but wasn’t levying taxes or making special claims on the treasury to get them constructed). Today, the King’s Castles are an important highlight of many a tour of southern Germany, and as mentioned above, Wagner might be as obscure as Salieri, had it not been for Ludwig’s patronage – all in all, not a bad legacy for an anguished man who found himself constrained to the breaking point by the homophobic mores of his day.

Historiorant:

There could have been dozens more case studies in this diary – Nero and George III were present in an earlier (read: in my head) draft – but you guys know me: I never met an obscure avenue of context that I could resist exploring. Hence, only two crazy kings in this one – and, hopefully, a recognition that calling a leader “crazy” isn’t always as definitive as might generally be implied. Gaius’ reputation may be due in part to a Swiftboating 2000 years in the making, while understanding the depth of Ludwig of Bavaria’s anguish gives us a clue as to why he would use his resources to build fairy-tale refuges – and the jury’s still way, way out on the bozo currently defiling our nation’s highest office.

So I leave to you, dear Cave-dwellers, to bring in some more show-n-tell examples of monarchs who’ve taken leave of their faculties. I consciously steered clear of the true psychopaths in my report – it was that kind of week – so perhaps we could start there, or maybe you’re more in the mood for some murmuring, drug-addled paranoia, a la Nixon…

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

who’s the craziest King of all?

He totally kicked that ocean’s ass. Had his soldiers beat the waves with swords and carry home shells as war spoils. That’ll show that stupid water!

I have to run over to Dkos and give you a rec and then I will be back to read. lol!

I found this fascinating, Brother Moonbat! Thank you.

I’ve done a bit of reading on George III, who had porphyria and possibley arsenic poisoning.

Thought disorders and behaviours of these individuals could have been due to physical and nutritional disorders.

http://www.alternati…

Have visited Neuschwanstein.

George III. Poor old lad. I once sent Blair the following (ish):

Koenig Georg XXXXIII is I feel, not suffering the effects of deadly slow poison. He is that worst of all loonies – a murderous howler possessed by the demon of murder and the goblin of greed.