Greetings, literature-loving Dharmiacs! Last week we sailed to ancient Mesopotamia to search for everlasting life with the great king Gilgamesh, and along the way we learned about ancient Sumeria from the venerable Moonbat. This week we’ll jump forward to 19th century America, where a journalist with a bitter sense of humor is reshaping the horrors of war into brutally incisive portraits of human nature.

Greetings, literature-loving Dharmiacs! Last week we sailed to ancient Mesopotamia to search for everlasting life with the great king Gilgamesh, and along the way we learned about ancient Sumeria from the venerable Moonbat. This week we’ll jump forward to 19th century America, where a journalist with a bitter sense of humor is reshaping the horrors of war into brutally incisive portraits of human nature.

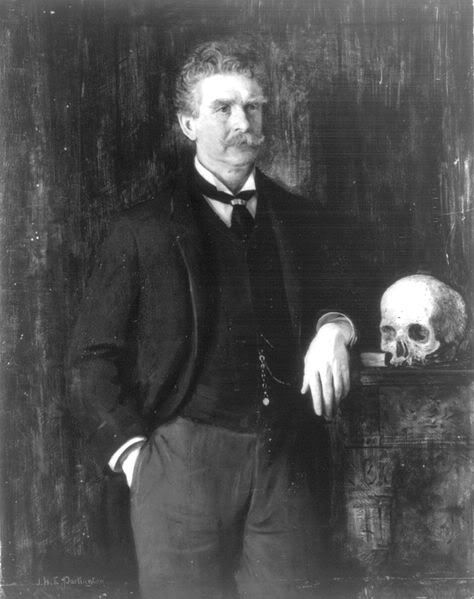

Ambrose Bierce: soldier, journalist, war correspondent. He fought in the most brutal Civil War battles and waged a one-man war against the entrenched interests of Big Railroad in California. He moved in all levels of society both here and abroad, then disappeared during the Mexican revolution, possibly killed by Pancho Villa’s forces. He was suspicious of politicians as of human nature in general, and since his death has become synonymous with acidic misanthropy.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the works of this distinctly American writer…

No country is so wild and difficult but men will make it a theatre of war.

— from “A Horseman in the Sky

The Misanthrope

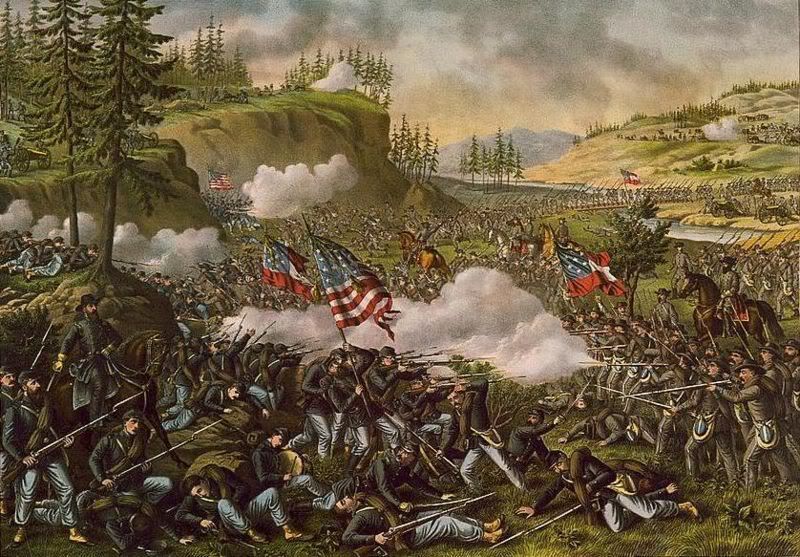

Bierce’s biography is almost more interesting than any of his stories. Born in Ohio in 1842, Ambrose Gwinett Bierce volunteered for the Union army 1860. The eighteen year old would soon find himself in the front lines of some of the worst fighting, including the battle of Chickamauga (which we’ll return to later).

Bierce’s biography is almost more interesting than any of his stories. Born in Ohio in 1842, Ambrose Gwinett Bierce volunteered for the Union army 1860. The eighteen year old would soon find himself in the front lines of some of the worst fighting, including the battle of Chickamauga (which we’ll return to later).

Bierce was wounded and discharged, later working both as a military inspector and with the Department of the Treasury. Eventually he abandoned all these professions (he hated them) to become a self-taught journalist in California. After his marriage to a local socialite and brief sojourn in England, Bierce returned to work with William Randolph Hearst, who gave him enough backing to challenge – successfully – the railroad magnates’ grip on California law. Though his writing could be impenetrably negative, he nonetheless fought as an advocate for public interest.

His death – or lack thereof – has become the stuff of legends. Already in his 70s, Bierce informed his family that he was traveling to Mexico to report on the battle between Pancho Villa’s rebel forces and the Federal army. Some say he met Villa and was eventually killed by the rebel leader for his incisive mockery of his campaign. Some say he was murdered by the Federal troops when they discovered he wanted to meet Villa. Still others assert that Bierce never made it to Mexico at all, but staged the whole trip as a ruse while committing suicide in isolation. Other versions are even stranger.

We’ll likely never know what really happened to Bierce in the end, but we have a body of literary work that we can still enjoy. Let’s take a look at some specific pieces:

Satire

Bierce was first and foremost a satirist, and even his most horrifying war stories contain poisonous little drops of his infamously toxic humor. He had little tolerance for humanity, and though reading too much Bierce can cause indigestion, there are few writers as potent in small doses.

He loved to shock people, and in this area “Oil of Dog” is one of his most successful efforts. A twisted tale that mines humor out of taboo topics, “Oil of Dog” is certainly the work of a provocateur, but an immensely talented one. The narrator’s mother is a back-alley abortion provider, and his father makes oil out of ‘stray’ dogs. Comparing his parents, the narrator notes,

My father’s business of making dog-oil was, naturally, less unpopular, though the owners of missing dogs sometimes regarded him with suspicion, which was reflected, to some extent, upon me. My father had, as silent partners, all the physicians of the town, who seldom wrote a prescription which did not contain what they were pleased to designate as Ol. can.

The rest of the story is so potentially offensive that I won’t post any excerpts. Read it if you’re not easily offended – it’s funny and audacious, especially considering that it was written in the 19th century. As modern readers we’re sometimes fed a ‘respectable’ version of literary history that leads to a narrow and stuffy portrait of that past that’s all quill pens and social mores. “Oil of Dog” will be a good shock to your system.

While his satirical stories are certainly very good, the crowning work of Bierce’s satire is undoubtedly his work as a lexicographer:

The Devil’s Dictionary

Directly inspired by Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas, Bierce’s own dictionary is much funnier and much more acidic in its views on human nature.

Where to start? Open any page of the Devil’s Dictionary (here’s an online version) and you’ll find aphoristic nuggets like

ABSCOND, v.i. To “move in a mysterious way,” commonly with the property of another.

or

TELEPHONE, n. An invention of the devil which abrogates some of the advantages of making a disagreeable person keep his distance.

or

PATRIOTISM, n. Combustible rubbish read to the torch of any one ambitious to illuminate his name.

In Dr. Johnson’s famous dictionary patriotism is defined as the last resort of a scoundrel. With all due respect to an enlightened but inferior lexicographer I beg to submit that it is the first.

I particularly like that last one, and it’s worth pointing out that Bierce, who fought as a soldier for the Union army and later worked as an American war journalist, held nothing but contempt for people who used patriotism as a shield against criticism of policy. Plus ca change…

Some of you have noted that I use a quote from the Devil’s Dictionary as my signature line:

SAINT, n. A dead sinner revised and edited.

It’s pithy, but also a bit deeper than it first looks. For Bierce, an idol always demands an iconoclast – not for its own sake, but to expose the shallowness of idolatry. Nevertheless we persist in seeking idols, whether religious or secular, conservative or liberal: this is an area in which we are all guilty. To force ourselves to acknowledge the flawed humanity of our idols is difficult but necessary – and someone like Bierce will be waiting to shatter them with a sledgehammer.

Horror

As a literary descendant of Edgar Allen Poe, Bierce also had an interest in horror, although his work in this area is not always as effective as the rest. Still, it’s worthwhile reading to get a better understanding of Bierce as a writer

As a literary descendant of Edgar Allen Poe, Bierce also had an interest in horror, although his work in this area is not always as effective as the rest. Still, it’s worthwhile reading to get a better understanding of Bierce as a writer

“The Damned Thing” is the most well-known, and was recently the inspiration for a (terrible) segment of the Masters of Horror series. The term ‘inspiration’ is extremely loose here: they have almost nothing in common, to the detriment of the movie.

“The Damned Thing” concerns the mysterious death of Hugh Morgan, who had invited the narrator to visit him on the pretense of a friendly stay: in fact, Morgan wanted someone else to witness the ‘thing’ that had been terrorizing him at his home. Instead, the narrator plays witness to his ugly death at the hands of an unseen beast:

At a distance of less than thirty yards was my friend, down upon one knee, his head thrown back at a frightful angle, hatless, his long hair in disorder and his whole body in violent movement from side to side, backward and forward. His right arm was lifted and seemed to lack the hand–at least, I could see none. The other arm was invisible. At times, as my memory now reports this extraordinary scene, I could discern but a part of his body; it was as if he had been partly blotted out.

The effect of “The Damned Thing” is more interesting than horrifying, but still a worthwhile read – especially if you want to know more about the development of horror as a literary genre. Bierce lacks Poe’s command of mood and language, at least when writing directly for readers of horror. But Bierce could mine the horrifying much more effectively when he was writing about an entirely different topic:

War

The fighting had been hard and continuous; that was atested by all the senses. The very taste of battle was in the air. All was now over; it remained only to succor the wounded and bury the dead–to “tidy up a bit,” as the humorist of a burial squad put it. A good deal of “tidying up” was required. As far as one could see through the forests, among the splintered trees, lay wrecks of men and horses.

—from “The Coup de Grace”

The larger part of Bierce’s misanthropy came through his experiences as a soldier, so it should be no surprise that his best stories involve the inhumanity, confusion, and despair of the Civil War. While his satire is sometimes dated by contemporary references, the war stories are still as immediate and affecting as ever.

Most of these stories were published in the collection Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (also published under In the Midst of Life), and all of them can be read online. You’ll notice some common themes: the ability of war to push people into acts of aggression they never dreamed they were capable of; the shifting consciousness that trauma can cause – a dream-like state where reality and unreality collapse; the tiny drop of acid humor in the sea of blood.

Among my favorites is “The Coup de Grace“, a typically Bierceian mix of humor and horror, with an ‘open’ ending that allows the reader to guess what happens next… although you’d have to be a really optimistic person to imagine that it ends well. The story’s ‘twist’ isn’t hard to see coming, but beyond the superficial simplicity is a thought-provoking rumination on the nature of friendship and kinship (fitting for a story about the Civil War), and on the extreme decisions that war elicits.

Two of these stories merit a much closer look:

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge

“Owl Creek” is Bierce’s most famous work of literature, partly because of its canonical appearance in literary anthologies, party because of the excellent, Oscar-winning adaptation later syndicated as part of the Twilight Zone series. Its unconventional narrative and radical expression of states of consciousness (keep in mind this was written in 1891) have led the story to be considered an important precursor to the experimental fiction of the 20th century.

The story concerns the hanging of Peter Farhquhar, a Southern farmer accused of aiding the Confederate army:

Evidently this was no vulgar assassin. The liberal military code makes provision for hanging many kinds of persons, and gentlemen are not excluded.

It’s impossible to summarize the story well without giving away its famous twist ending. For the two of you who haven’t read it, here’s the full text. For the rest of you, should you decide to reread it, take special note of the shifting verb tenses at the end of the story: this is one of the ways that Bierce inserts the story’s theme into its very form. The effect is jarring once you notice it – but very effective.

Chickamauga

In my mind, “Chickamauga” is the greatest of all war stories, a brutal distillation of horror in a handful of unforgettable pages. Bierce accomplished what many writers before and after him have not: to transmit the soul-crushing terror of his experience as a soldier into an artificial narrative structure, and to do it without a whiff of sentimentality.

This is even more surprising since the ‘hero’ of the story is a little child who finds himself lost in the aftermath of the Civil War’s most brutal battle: hardly the kind of setup you’d expect to avoid sentimentality. But Bierce does it with a nifty 2-part structure: the first half of the story is all satire, using the child as an ugly mirror of the adult world’s fixation with all things bellicose:

The man loved military books and pictures and the boy had understood enough to make himself a wooden sword, though even the eye of his father would hardly have known it for what it was. This weapon he now bore bravely, as became the son of an heroic race, and pausing now and again in the sunny space of the forest assumed, with some exaggeration, the postures of aggression and defense that he had been taught by the engraver’s art.

You can hear Bierce’s acid tongue behind phrases like “an heroic race” and the mockingly elevated diction, both devices that distance the reader from the child (especially as the story wears on). Following in the footsteps of his conquering people, the child wanders into the woods and soon finds himself lost. Tired and scared, he falls asleep between some rocks while his family searches for him in a panic.

What happens when the child wakes up, I’ll leave for you to discover: here is the full text of the story. It’s a short read, but the impact is powerful and the imagery will not soon leave your head. “Chickamauga” is Bierce’s masterpiece.

|

Links:

- The Ambrose Bierce Appreciate Society: awesome collection of links and information, including most of Bierce’s texts online;

- The Ambrose Bierce Project: a digital compendium of resources;

- More biography and links to texts at Online Literature and Kirjasto;

- IMDB listing for films based on Bierce’s works;

All texts are in the public domain, and all excerpts taken from the links provided. Images from wikimedia commons, with links back to their original attributions.

Thank you for reading.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

apologies that I don’t go quite as into depth as usual – but then again, Bierce is such a multifaceted writer that going into depth would mean less attention to each of his sides.

Author

that I didn’t post above?

Reading you is so much better than returning to college–Bierce is not a favorite, but I promise to do my homework.

The Damned Thing ….sounds like Lovecraft lifted it.

in Mexico is The Old Gringo by Carlos Fuentes, which should be highly recommended. Especially if one isn’t familiar with Latin American authors. The idea of the novel is that Bierce was trying to get himself killed in Mexico and this led to acts of heroism, recklessness that was not rewarded with his fatality. I’m not telling the story; it’s worth reading.

Bierce could be funnier and more cynical than Mark Twain, who Bierce detested with a passion for an insult. Mark Twain paid little heed and bested the old warrior in life and death. Such is the way of things.

Always love to hear mention of one dead sinner who will never be revised and edited.

Thank you.

Best, Terry