“There! You see? I was right! I was only thirty years too soon. What was treason in me thirty years ago, is patriotism now.”

— Aaron Burr, upon hearing of the Texas Revolt, 1836

Perhaps someday, if the neocon plan works out and America does manage to establish itself as the master of a global hegemony of subject nations and enslaved peoples, the 9% of our fellow citizens who don’t think Dick Cheney sucks will be able to point to some future event and try to use it to vindicate not impeaching the current veep now – but I rather doubt it. History is not kind to fools and poor leaders – and only occasionally rewards the schemers and the scammers – yet it has always been notoriously difficult to pry such men from perches of power, since the people with the ability to do so often lack the chutzpah of their intended target.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll meet a veep whose poor decision-making skills (and chutzpah) may have actually eclipsed those of Fourthbranch. We’ll also contemplate the scary truth that it wasn’t until after he’d left office that our first Treasonous Veep engaged in his zaniest schemes of usurpation.

Originally, the office was designed for runners-up. The Founding Fathers, in their pitiable naiveté, thought that the guy who came in second in a race for the presidency would naturally find solace in serving the country that had recently rejected his application for leadership, so the Office of the Vice Presidency was tossed into the Constitution almost as an afterthought. When this arrangement proved unworkable due to the rise of political parties and basic human nature (and in no small part, the actions of tonight’s subject), the Founders adopted the 12th Amendment, thereby ensuring that the second-fiddle office would often be filled by second-rate men. In an ethical sense at least, that trend continues to this day.

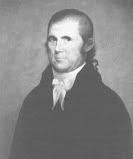

It could be argued, however, that the morality bar for the vice presidency had been set pretty low, pretty early on. In the last (rather ill-attended, tsk tsk) historiorant, I babbled about America’s third Vice President, whose actions in office included nothing less than the shooting and killing of the former Secretary of the Treasury. Still, in the end, that wasn’t what got Aaron Burr dragged before a judge (and not just any judge) on charges of treason – it was his part in a conspiracy to commit an act of illegal immigration of the north-to-south variety.

Who Needs Blackwater? I’ll Do It Myself!

By 1804, Aaron Burr didn’t have much to lose. He’d run against Thomas Jefferson for the presidency in 1800 and very nearly orchestrated a victory for himself, but when the dust settled and the House broke the electoral deadlock in TJ’s favor, he wound up with the number two slot. By all accounts, he did a fair and impartial job presiding over the Senate, but he was ostracized by a Washington society that was all about the guy who beat the Barbary Pirates and purchased Louisiana from Napoleon. Accurately perceiving that he had about as much chance of succeeding Jefferson as Cheney does Bush, Burr returned to his home in New York and sought the Democratic-Republican nomination in the governor’s race. Failing to secure it, he pulled a Lieberman and ran as an independent (lacking the Republican and turncoat Dem backing that his brother in slime got, Burr went on to lose by the largest margin in the state’s history).

By 1804, Aaron Burr didn’t have much to lose. He’d run against Thomas Jefferson for the presidency in 1800 and very nearly orchestrated a victory for himself, but when the dust settled and the House broke the electoral deadlock in TJ’s favor, he wound up with the number two slot. By all accounts, he did a fair and impartial job presiding over the Senate, but he was ostracized by a Washington society that was all about the guy who beat the Barbary Pirates and purchased Louisiana from Napoleon. Accurately perceiving that he had about as much chance of succeeding Jefferson as Cheney does Bush, Burr returned to his home in New York and sought the Democratic-Republican nomination in the governor’s race. Failing to secure it, he pulled a Lieberman and ran as an independent (lacking the Republican and turncoat Dem backing that his brother in slime got, Burr went on to lose by the largest margin in the state’s history).

The campaign was vicious, with the opposition being organized by no less a political operative than Alexander “$10 bill” Hamilton. In the midst of it all, both sides said the kind of things that you just can’t take back – Hamilton probably won in this regard when the claim was advanced by his side that Burr was sleeping with his own daughter – and events proceeded along a Zell Milleresque line of reasoning to their (il)logical conclusion: Hamilton lying mortally wounded on the ground in Weehawken, New Jersey, in the summer of 1804.

It would later be discovered that the former Treasury boss hadn’t exactly approached the matter with his honor intact; his pistol had been altered for a “hair trigger” effect; it required only about a half pound of pressure to fire, as opposed to the normal 10 to 12 pounds. Ironically, Hamilton’s attempt to cheat was probably his undoing, as his weapon discharged prematurely, leaving Burr with plenty of time to aim at his nemesis and fire a 56-caliber ball of lead at Hamilton. (hat tip to blueness and the several commenters who brought up some of these aspects of the duel last week – u.m.)

Burr was charged with murder in both New York and New Jersey, so he stuck to a succession of undisclosed locations for a few months. At a point early in his lam-travels, he made his way to Philadelphia, where he tried to involve the British minister to the U.S. in a scheme to separate the states west of the Appalachians from the Union. He also began conspiring (no, it’s not too strong a word) with General James Wilkinson, whom Burr had first met while serving under Benedict Arnold during the failed troop surge into Canada in 1775-76. Wilkinson had an unfocused resume of various important staff jobs around the Army as he first impressed, then pissed off, a succession of high-ranking officers (the job-bouncing might have been considered Cheney-like, were it not for the most un-Cheney-like fact that Wilkinson actually had the balls to join the Army when his country needed him) with a candor that makes the American Revolution sound like the Iraq Occupation:

Burr was charged with murder in both New York and New Jersey, so he stuck to a succession of undisclosed locations for a few months. At a point early in his lam-travels, he made his way to Philadelphia, where he tried to involve the British minister to the U.S. in a scheme to separate the states west of the Appalachians from the Union. He also began conspiring (no, it’s not too strong a word) with General James Wilkinson, whom Burr had first met while serving under Benedict Arnold during the failed troop surge into Canada in 1775-76. Wilkinson had an unfocused resume of various important staff jobs around the Army as he first impressed, then pissed off, a succession of high-ranking officers (the job-bouncing might have been considered Cheney-like, were it not for the most un-Cheney-like fact that Wilkinson actually had the balls to join the Army when his country needed him) with a candor that makes the American Revolution sound like the Iraq Occupation:

I have commented on the progress of this war, the imperfect manner in which all events are communicated to those whose station calls for the most accurate account of every material transaction. One characteristic is applicable to most of our public relations and is particularly applicable to those from this quarter. Fxaggeration of successful opperations [sic], diminution to adverse. From hence arises those false hopes which influence our councils and operate on the exertions of the people. This single consideration ought to influence to perfect communication between those in the field, and those at the head of affairs.

All served-together-under-a-traitor and frustrated-Machiavellian-prince ironies aside, Burr and Wilkinson were peas in a pod when it came to deviousness. Between them, they had arranged a cipher with which to communicate, and now began plotting in earnest how to carve themselves a little kingdom out of Spanish territory west of Louisiana.

“the most consummate artist in treason that the nation ever possessed.”

– Frederick Jackson Turner

Wilkinson was no stranger to dealings with the Spanish – he’d been on their government’s payroll since 1787 – and he had plotted to sell out the United States before. Like Cheney groveling before the oil sheiks, Wilkinson had tried to come to an arrangement with the King of Spain, whereby Kentucky would divorce itself from Virginia and the United States, and would thereafter dedicate itself to supporting Spanish interests west of the Mississippi. A letter he wrote to the King has the odd air of Cheney selecting a running mate for a presidential candidate about it:

His description of the ideal man for this position implied that he was recommending himself:

I comprehend that it is not out of reason that a man of great popularity and political talents, co-operating with the causes above mentioned, will be able to alienate the Western Americans from the United States, destroy the insidious designs of Great Britain and throw those (Western Americans) into the arms of Spain.

Nothing much ever came of Wilkinson’s plans for an independent Kentucky and alliance with Spain; he was frustrated by parliamentary dealings related to adoption of the Constitution and Kentucky’s status as a state, and his support ebbed away. Though he continued to receive secret payments from the Spanish government for many years, the Spanish governor was instructed not to extend to him any of the bribes land grants and monopolistic river-trade concessions for which Wilkinson had asked, and the “Spanish Conspiracy” quietly came to an end.

Wilkinson had quite the name-dropping career in the decade and a half before he and Burr reignited the old schemes of western empire. In 1791, he donned the uniform once again to fight Indians along the Ohio River, and served under “Mad Anthony” Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. There, Wilkinson commanded the right flank of Wayne’s forces, among which included a young William Henry Harrison, destined to be the ninth President of the United States and the first to pass on the office to his veep. By 1800, Wilkinson was the senior officer in the U.S. Army, and in 1805, President Jefferson made him governor of the newly-organized Louisiana Territory.

To Blennerhassett’s Island…and Beyond!

Though it’s difficult to tell who, exactly, came up with the plan (or even if Alexander Hamilton had had a similar one of his own), Wilkinson’s career advancement fit perfectly into it. He would now have troops at his command, and it would be a simple procedure to either secure their support for a rebellion, or to have them otherwise (and otherwhere) occupied should one happen to come about. Burr set out organizing the fundraising, paying visits to all the rich, seditious types he could think of; being Dick Cheney’s soul-ancestor, he could think of quite a few. Chief among these was one Anthony Merry, His Majesty’s Minister to the United States, and his lordship doesn’t seem to have been all that opposed to Burr’s ideas:

I am encouraged to report to your Lordship the substance of some secret communications which [Burr] has sought to make to me since he has been out of office…Mr. Burr has mentioned to me that the inhabitants of Louisiana [the lands recently purchased from France] seem determined to render themselves independent of the United States and the execution of their design is only delayed by the difficulty of obtaining previously an assurance of protection and assistance from some foreign power….It is clear that Mr. Burr means to endeavor to be the instrument for effecting such a connection….He pointed out the great commercial advantage which his Majesty’s dominions in general would derive from furnishing almost exclusively (as they might through Canada and New Orleans) the inhabitants of so extensive a territory…

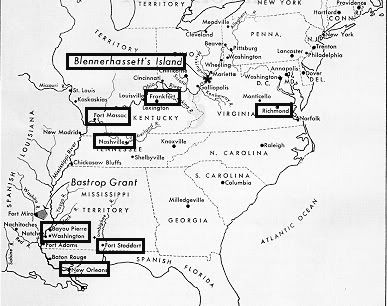

He might’ve raised some British eyebrows, but there wouldn’t be any frigates forthcoming, so Burr made his way west, arriving at Pittsburgh on April 29, 1805. He had hoped to meet with Wilkinson there, but as the General had been delayed, Burr set off down the Ohio in a specially-outfitted boat he termed his “ark.” Soon he found himself alighting on the shores of Blennerhassett’s Island, now a West Virginia (hi Carnacki!) State Park, but then an island paradise inhabited by wealthy and refined Irish immigrant Harman Blennerhassett. Since his arrival in the States in 1796, Blennerhassett had been collecting books and creating what some visitors described as “Eden” or an “enchanted isle” on his 300-acre spread, and when Burr rafted up, it was natural that he and Blennerhassett would talk deep into the night. Later that year, he signed on to Burr’s cause:

He might’ve raised some British eyebrows, but there wouldn’t be any frigates forthcoming, so Burr made his way west, arriving at Pittsburgh on April 29, 1805. He had hoped to meet with Wilkinson there, but as the General had been delayed, Burr set off down the Ohio in a specially-outfitted boat he termed his “ark.” Soon he found himself alighting on the shores of Blennerhassett’s Island, now a West Virginia (hi Carnacki!) State Park, but then an island paradise inhabited by wealthy and refined Irish immigrant Harman Blennerhassett. Since his arrival in the States in 1796, Blennerhassett had been collecting books and creating what some visitors described as “Eden” or an “enchanted isle” on his 300-acre spread, and when Burr rafted up, it was natural that he and Blennerhassett would talk deep into the night. Later that year, he signed on to Burr’s cause:

I should be honored in being associated with you, in any contemplated enterprise you would permit me to participate in….Viewing the probability of a rupture with Spain,…I am disposed, in the confidential spirit of this letter, to offer you and my friends’ and my own services in any contemplated measures in which you may embark.

Burr kept up the recruiting drive as he sailed down the river. He met with former Senator John Dayton in Cincinnati, and there presumably cemented the deal that would later see them tried together for treason, then left the ark in Louisville while he traveled overland to Nashville. Burr stayed as a guest of General Andrew Jackson before continuing to Fort Massac (now a State Park on the southern tip of Illinois, overlooking the Ohio River), where he finally got a chance for some good ole fashion’ collusion with General Wilkinson.

Burr took to the Mississippi on an “elegant barge” given to him by Wilkinson, and had the General’s letters of introduction on hand when he arrived at New Orleans. There he met with Daniel Clark, a slime-buddy of Wilkinson’s since back in the old Spanish Conspiracy days. Burr apparently promised Clark a dukedom in the empire tomorrow in exchange for 50,000 bucks today; Clark was so on-board that he traveled to Mexico to assess defenses and the public mood regarding regime change. This, of course, betrays an un-Cheneyism in Burr’s schemes – Cheney would never waste time gathering intelligence on a presumed target, and certainly could not be counted upon to go and get it himself.

Burr took to the Mississippi on an “elegant barge” given to him by Wilkinson, and had the General’s letters of introduction on hand when he arrived at New Orleans. There he met with Daniel Clark, a slime-buddy of Wilkinson’s since back in the old Spanish Conspiracy days. Burr apparently promised Clark a dukedom in the empire tomorrow in exchange for 50,000 bucks today; Clark was so on-board that he traveled to Mexico to assess defenses and the public mood regarding regime change. This, of course, betrays an un-Cheneyism in Burr’s schemes – Cheney would never waste time gathering intelligence on a presumed target, and certainly could not be counted upon to go and get it himself.

Whenever Wilkinson got a new job, it was, Bush-like, just a matter of time before his self-serving personality asserted itself and he started running afoul of the higher-ups. He knew this as well as anyone, so when he got wind that people were already complaining about his ham-handed administration of the new territory, the ever-wily Wilkinson started hedging his bets. After Burr visited him in St. Louis in the summer of 1805, ostensibly to finalize plans for their joint operation, Wilkinson started laying the groundwork for later whistle-blowing by writing a letter to the President quoting Burr’s seditious ramblings.

The Trial of Aaron Burr: Map Showing Key Locations

Burr, meanwhile, was aggressively, if secretly, fundraising and traveling about. The winter of 1805-06 found him back in Washington, talking to disaffected officers, and his recruiting continued when he headed west again – this time with his daughter Theodosia and her young son in tow. He headed up to western Pennsylvania, where at a dinner with an influential local pol named Colonel Morgan and his son, a General, Burr seems to have forgotten the first rule of villainy: Never expose your plans to anyone not known to be as corrupt as you are.

Unbeknownst to Burr, Colonel Morgan wrote a letter to President Jefferson that would become a whistleblower’s classic, even as Burr got his logistical ducks in a row. By the end of August, he was back at Blennerhasset’s Island, awaiting shipments of pork, cornmeal, whiskey, flour, 15 transport vessels (about 500 soldiers’ worth), and a keel-boat for hauling all the guns and butter. Later, he paid Andrew Jackson $4000 for six more boats, and bought a 300,000-acre chunk of territory on the Washita River called the Bastrop Land to serve as either a staging area, feudal baronies after victory, or a fall-back position/legitimate land-speculation cover, depending on whose story one believes.

Honor Among Thieves

It’s hard to know what motivated General Wilkinson to turn on his erstwhile partner in crime, but he did. That he reported to President Jefferson the contents of a ciphered letter which read, in part,

I have obtained funds, and have actually commenced the enterprise. Detachments from different points under different pretenses will rendezvous on the Ohio, 1st November– everything internal and external favors views–protection of England is secured. T[ruxton] is gone to Jamaica to arrange with the admiral on that station, and will meet at the Mississippi– England—Navy of the United States are ready to join, and final orders are given to my friends and followers–it will be a host of choice spirits. Wilkinson shall be second to Burr only–Wilkinson shall dictate the rank and promotion of his officers.

…ought to give us hope: Wilkinson’s betrayal of the betrayer proves that even dirtballs are capable of patriotic whistleblowing, whatever their self-serving motivations might be. In his case, the General/governor raised the alert status at New Orleans to Elmo, and moved his troops to protect the approaches to the Mississippi Valley.

…ought to give us hope: Wilkinson’s betrayal of the betrayer proves that even dirtballs are capable of patriotic whistleblowing, whatever their self-serving motivations might be. In his case, the General/governor raised the alert status at New Orleans to Elmo, and moved his troops to protect the approaches to the Mississippi Valley.

Jefferson, now at DefCon 2, moved swiftly against Burr. He issued a proclamation declaring an insurgency afoot, and urged all government and military types to spend some time “searching out and bringing to condign punishment all persons engaged or concerned in such enterprise.” He also dispatched a State Department clerk/agent/spy named Graham to give Burr’s plot the Mission Impossible treatment, and it seems the guy was up to the task. Graham fooled old Harman Blennerhassett into thinking he was in on the game, and Blennerhassett unwittingly revealed a few choice details – classic human intelligence of the sort poo-pooed by our Predator-loving Number Two.

Graham trekked over to Chillicothe, Ohio (then the capital) and convinced the governor to send the militia to Marietta, where Burr’s undelivered boats were being stored. When they arrived, they found 11 of the 15 boats prepared for delivery the next day; the other 4 were already at Blennerhassett’s Island, along with 3 conspirators and about 30 Blackwater types. These quickly got word that the plan was falling apart, and they left the island just before the militia arrived the next morning. Angry at having missed their quarry, the militia acted like looters in a Baghdad museum, trashing furniture and art, firing bullets into the ceiling, and drinking from the gentleman’s private whiskey cellar.

Burr was in Nashville when he heard that the feds were on to him, so he fled north to a predetermined rendezvous at the Falls of the Ohio. At this point, he still thought Wilkinson was on his side; he didn’t become aware of the General’s duplicity until he reached Bayou Pierre, about 30 miles north of Natchez. Realizing that the jig was up, Burr moved to cover himself with one of the most Dana Perino-sounding letters of the early 19th century:

“If the alarm which has been excited should not be appeased by this declaration, I invite my fellow citizens to visit me at this place, and to receive from me, in person, such further explanations as may be necessary to their satisfaction, presuming that when my views are understood, they will receive the countenance of all good men.”

The ex-veep had between 60 and 100 men with him, but they didn’t fire on the 30-man detachment of Mississippi militia that delivered a letter from their governor demanding Burr’s surrender. Burr did so the next day after meeting with the governor, and was declared by a grand jury in the town of Washington to be “not guilty of any crime or misdemeanor against the United States.” Since back in those days it was unacceptable to hold a citizen without charges, the governor was forced to grant Burr his freedom, and the would-be emperor disguised himself as a boatman and slipped into the swamps.

Mounting evidence compelled the issuance of a second warrant, and in February, 1807, Burr was re-arrested on the banks of the Tombigbee River, in present-day Alabama. He was held at an army fort for a couple of weeks, then escorted by nine armed men to Richmond, Virginia, to stand trial for treason.

Enemies (and friends) in High Places

The cast of characters in the Burr trial is a who’s who of early U.S. politics and jurisprudence. The driving force behind the prosecution was Thomas Jefferson, but the fact that Chief Justice John Marshall would preside over the trial threw a kink into things, as there was no love lost between the two men. A former Attorney General (the office was somewhat less tarnished in those days; being an ex-AG didn’t necessarily mean that one was a disgraced, incompetent boob) and future presidential candidate argued for the prosecution, and two attendees of the Constitutional Convention presented the defense. The trial was preceded by an examination, during which Burr professed “who, me?,” and the Chief Justice considered various pretrial motions.

The cast of characters in the Burr trial is a who’s who of early U.S. politics and jurisprudence. The driving force behind the prosecution was Thomas Jefferson, but the fact that Chief Justice John Marshall would preside over the trial threw a kink into things, as there was no love lost between the two men. A former Attorney General (the office was somewhat less tarnished in those days; being an ex-AG didn’t necessarily mean that one was a disgraced, incompetent boob) and future presidential candidate argued for the prosecution, and two attendees of the Constitutional Convention presented the defense. The trial was preceded by an examination, during which Burr professed “who, me?,” and the Chief Justice considered various pretrial motions.

Marshall issued his opinion on April Fool’s Day, 1807, and decreed that there was insufficient evidence to charge Burr with treason, but that he’d be held on $10,000 bail and charged with a high misdemeanor. The case was to be taken up by a grand jury in a few weeks. Jefferson went into an evidence-collecting frenzy, even going so far as to have his Secretary of State, James Madison, write to Andrew Jackson asking for the future Old Hickory to go around Nashville collecting anti-Burr depositions; this series of letters gives some indication of how Jefferson regarded his ex-veep’s actions. Still, he was going to have his work cut out for him, if he wanted to secure a conviction:

The prosecution, noting that “the evidence is different now,” again moved for commitment of Burr on the charge of treason. The defense countered, arguing that to establish the crime of treason the prosecution must prove that an overt act of treason had been committed by the defendant in a war and that, under the Constitution, the overt act must be testified to by two witnesses and must have occurred in the district of the trial. When Marshall sided with the defense’s narrow interpretation of treason, the prosecution knew it had its back to the wall.

ibid. (emphasis original)

Marshall also considered a motion by the defense to subpoena certain of Wilkinson’s letters, then in Jefferson’s possession, that might help Burr’s case, but even though the Chief Justice issued just such a subpoena, Jefferson ignored the order. Thus, in a case full of precedents that didn’t necessarily bode well for we of the Bush/Cheney era, Jefferson dropped a doozy – his explanation sounds almost contemporary:

The leading feature of our Constitution is the independence of the Legislative, Executive, and Judiciary of each other; and none are more jealous of this than the Judiciary. But would the Executive be independent of the Judiciary if he were subject to the commands of the latter, and to imprisonment for disobedience; if the smaller courts could bandy him from pillar to post, keep him constantly trudging from north to south and east to west, and withdraw him entirely from his executive duties?

In June, Wilkinson himself arrived in Richmond, and entered the room with what author/Nancy Grace fan Washington Irving termed a “strut,” afterwhich the General “stood for a moment swelling like a turkey-cock.” His testimony was enough for the grand jury to return an indictment on treason charges.

The trial commenced on August 3, 1807, in an overflowing Virginia Hall of Delegates. The prosecution produced a parade of witnesses who clearly placed Burr at the heart of a conspiracy, but after a couple of weeks of listening to them, Burr’s side issued a motion to arrest any further evidence that didn’t serve to prove an actual crime had been committed. Since back in March, Burr had been insisting that this was all just a big misunderstanding

that the manner of his descent down the river was a fact which put at defiance all rumors about treason and misdemeanor; that the nature of his equipments clearly evinced that his object was purely peaceable and agricultural; that this fact alone ought to overthrow the testimony against him; that his designs were honorable, and would have been useful to the United States.

…and besides, he’d been over 100 miles away from the single overt act of treason (the gathering of forces at Blannerhassett’s Island) that was being alleged. Marshall’s regrettable decision – which took three hours for him to read – agreed with Burr, and in so doing set a very high bar for proof of treason. “If those who perpetrated the fact be not traitors, he who advised them [Burr] cannot be a traitor,” he intoned. He then instructed the jury to disregard any testimony related to treasonous events which may or may not have occurred on the Island. Their hands tied by one of the greatest legal minds of the age, the jury didn’t have much choice but to find Burr not guilty, but in so doing, they delivered a slight barb at the Chief Justice who’d done the tying:

“We of the jury say that Aaron Burr is not proved to be guilty under this indictment by any evidence submitted to us. We therefore find him not guilty.”

Historiorant

Jefferson had a pretty good inkling of what could come of all this:

The scenes which have been acted at Richmond are such as have never been exhibited in any country, where all regard to public character has not yet been thrown off. They are equivalent to a proclamation of impunity to every traitorous combination which may be formed to destroy the Union.

…but John Marshall didn’t care, and after a while, neither did anybody else. Utterly disgraced, Burr slithered off to Europe, where even Napoleon got hit up for a chance to support another Burr plot at Southwestern glory. Failing to find any takers, he quietly returned to New York in 1812, and was greeted by two crushing blows: first news of his grandson’s death, then the loss at sea of his beloved daughter Theodosia. Settling in to a life of lonely misery, he became a moderately successful attorney. In 1833, at the age of 77, he married a widow named Eliza Jumel. She was granted a divorce on the day he died – September 14, 1836, just a few months after the Battles of the Alamo and San Jacinto secured the independence of the Republic of Texas.

Aaron Burr is not the perfect analogy for Dick Cheney – the types of crimes in which they engage/d are quite different, among a thousand other discrepancies – but as I mentioned in Episode I, my point isn’t so much to try to wrench a parallel tale out of a pair of miscreants who lived 200 years apart as it is showing that we need not so frequently resort to hyperbolic expressions like “Darth Cheney” and all that other futuristic/satanic imagery conjured up by a mention of the his name – all we have to do is recall that our own history already contains dirtbaggery on a truly Vice Presidential scale. If you don’t believe me, wait’ll you hear about John C. Breckenridge…

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, and DocuDharma.

8 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

the more they seem to stay the same, no?

I always love the history that you share….

over and over agian it becomes clear that very little has changed in the last several thousand years…

only the consequences have increased exponentialy…..

thank you…..

for which I thank you.

about Aaron Burr’s attempt to overthrow the government, I found this very interesting with today’s references..many of the details do seem parallel, if not entirely, taken singly, there is something to be learned here. If only we had some men of Jefferson’s caliber to stand up for the Constitution. Cheney should be tried for treason…but with the SCOTUS we have today, like Burr’s charges, it probably wouldn’t stick.

I enjoyed this very much…Thanks.

Thanks Mr bat!

to view the treasures in the lapidary mind of our friend Unitary Moonbat.