Greetings, literature-loving Dharmiacs. Last time we discussed gay Harlem Renaissance author Richard Bruce Nugent, who tapped into the experimental cadences of black modernist literature to spin fantasies on queer life long before it became acceptable to do so. This week we’re going to talk about another American experimental writer, albeit one who achieved enormous popularity both at home and abroad.

Greetings, literature-loving Dharmiacs. Last time we discussed gay Harlem Renaissance author Richard Bruce Nugent, who tapped into the experimental cadences of black modernist literature to spin fantasies on queer life long before it became acceptable to do so. This week we’re going to talk about another American experimental writer, albeit one who achieved enormous popularity both at home and abroad.

With torture and extraordinary rendition so much in the news, it may come as something as a surprise that today’s subject experienced the agony of unjust political imprisonment first hand. But in 1917, this recent Harvard graduate and volunteer in a World War I ambulance corps found himself thrown in prison for “espionage” without recourse to any legal defense. Fortunately for history (and for us) the experience did nothing to crush his puckish personality, and he went on to become one of America’s most warmly loved artists.

Follow me below for a jaunt with this 20th century master:

Poet, novelist, painter, and all-around shit-stirrer Edward Estlin Cummings was born in 1894 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After graduating magna cum laude from Harvard, he skipped to France with his old college buddy John Dos Passos and quickly fell in love with the vibrant art scene (especially American) in Paris. That artistic growth was cut short – or, if you will, significantly advanced – when he was arrested on suspicion of espionage and interred in the village of La Ferté-Macé. While his father fought for his removal by contacting anyone he could, Cummings himself was discovering the joys of political prisonerhood, an experience he’d memorably capture in his novel The Enormous Room.

Poet, novelist, painter, and all-around shit-stirrer Edward Estlin Cummings was born in 1894 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After graduating magna cum laude from Harvard, he skipped to France with his old college buddy John Dos Passos and quickly fell in love with the vibrant art scene (especially American) in Paris. That artistic growth was cut short – or, if you will, significantly advanced – when he was arrested on suspicion of espionage and interred in the village of La Ferté-Macé. While his father fought for his removal by contacting anyone he could, Cummings himself was discovering the joys of political prisonerhood, an experience he’d memorably capture in his novel The Enormous Room.

Throughout his life Cummings sought experience in the world: he lived in Paris and New York, traveled to the Soviet Union, North Africa, and Mexico, and incorporated the breadth and depth of life into his enormous poetic output. In the meantime he developed an idiosyncratic style of poetry that managed to be disorienting and surprising without putting off readers: as far as avant garde poets go, Cummings is easily the most popular this country has produced (although it’s equally fair to argue that his poetry is usually only avant garde on the surface, while the often otherwise conventional poem underneath in some way accounts for his approachability. I’m not sure I agree 100%, but that’s a not uncommon view.)

Today I want to talk a bit about what makes Cummings so popular, but also – and especially – to encourage people to pick up his first novel, which has a great deal to say about culture of indefinite and indiscriminate imprisonment and the way it is used to stifle dissent in countries that nonetheless need it. So first, The Enormous Room:

A quick note on the spelling of the author’s name: Norman Friedman has made a compelling argument that caps are called for, and the correct presentation is E.E.Cummings. Friedman cites a letter from Cummings to his publisher, specifically rejecting the lowercase, punctuation-less form of his name: “E.E.Cummings, unless your printer prefers E. E. Cummings/ titlepage up to you;but may it not be tricksy svp[.]” Now, does anyone want to place bets on whether over-eager readers skip this to leave me a comment correcting my usage? 🙂

The Enormous Room

Everyone is here for something.

The Enormous Room (full text!) is Cummings’ prose masterpiece, a fast-paced comic brawl with a warm moral heart, a portrait gallery of eccentricity and lunacy and humanity surviving under the shadow of authoritarian cruelty, an exuberant middle finger to authority and a passionate plea for humanity. And it all takes place in a cramped camp where dubiously labeled ‘political prisoners’ are being held with no chance of legal consul or defense.

In other words, it’s the perfect book for our time.

Cummings transformed his experience as a ‘political prisoner’ into a vibrant testament to the human experience, but not in the way you might expect. Rather than a litany of suffering appealing to the reader’s moral sense (although there is plenty of both in the book), the main technique of Cummings’ work is humor: the absurdity of the situation cannot be ignored, and might as well be enjoyed. The jovial narrator spins tales of friendships, gambling, defiance, bureaucracy, and freedom, all the while wearing a giant smile. That humor – that inability to be crushed by a cold and fearful political machine – is itself the ultimate statement of his defiance.

The absurdity begins in the first chapter: according to Cummings’ version of the events, he did not need to go to prison at all. His acquisition was one part solidarity with his unfairly sentenced friend, and one part puckish defiance: when the interrogator Noyon decided to throw out one last, loathsome question (“Do you hate the Krauts?”), Cummings refused to give the “correct” answer, even in front of a sympathetic military tribunal (referred to by their most exaggerated physical qualities: “the rosette”, “the moustache”):

‘Est-ce que vous détestez les boches?’

I had won my own case. The question was purely perfunctory. To walk out of the room a free man I had merely to say yes. My examiners were sure of my answer. The rosette was leaning forward and smiling encouragingly. The moustache was making little oui’s in the air with his pen. And Noyon had given up all hope of making me out a criminal. I might be rash, but I was innocent; the dupe of a superior and malign intelligence. I would probably be admonished to choose my friends more carefully next time, and that would be all….

Deliberately, I framed the answer:

‘Non. J’aime beaucoup les français.’

Agile as a weasel, Monsieur le Ministre was on top of me: ‘It is impossible to love Frenchmen and not to hate Germans.’ (15)

The Enormous Room is less a narrative than a portrait gallery, and this contributes a great deal to the book’s warm humanism. After all, before gaining notoriety as a poet, Cummings worked as a painter – his sense of portraiture is exact and revealing. Each inmate of La Ferté is sketched from a lovingly comic angle, as if the artist Cummings can hardly conceal his joy at being imprisoned with such delightful company. Take for example Jean le Nègre:

[Jean’s] mind was like a child’s. His use of language was sometimes exalted fibbing, sometimes the purely picturesque. He courted above all the sounds of words, more or less disdaining their meaning. He told us immediately (in pidgin-French) that he was born without a mother because his mother died when he was born, that his father was (first) sixteen (then) sixty years old, that his father gagnait cinq cent francs par jour (later, par année), that he was born in London but not in England, that he was in the French army and had never been in any army.

He did not, however, contradict himself in one statement: ‘Les français sont de cochons’ – to which we heartily agreed, and which won him the approval of the Hollanders. (206)

Cummings and his friends rename everyone in the room, and soon the reader becomes acquainted with the strangest collection of “criminals” imaginable: the Machine-Fixer, the Silent Man, Emile the Bum, the Schoolmaster, Bathhouse John, the little man in the Orange cap, the Holland Skipper, Garibaldi, and my personal favorite: So-and-so, being a Turk.

The exaggerated nicknames initially feel like caricatures, but Cummings’ instincts are right on: by the book’s end, you’ll remember nearly every character and a bit of their back stories. The nomenclature shorthand makes everyone ‘stick’ in a way that dry lists of names would not.

Four of the prisoners receive their own chapters: the Delectable Mountains. As a framing device, Cummings loosely outlines his book according to John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Paradise, in which the Delectable Mountains were four peaks so high that one could see the Heavenly Kingdom. In The Enormous Room, the Delectable Mountains are four prisoners so pure of heart that their inclusion among the already eclectic band of misfits at La Ferté was the greatest crime of all: the Wanderer, Zulu (sometimes Zoo-loo) Surplice, and Jean le Nègre. Any system, Cummings argues, that is capable of putting men like these behind bars as “dangerous criminals” is a system rotten to the core; Cummings expresses great admiration for his fellow prisoners to endure (especially the women, who have it even worse).

In the nickname game, the French guards fare much worse: Cummings labels the head of La Ferté “Apollyon”, a nickname he certainly deserves for his casually brutal treatment of the prisoners. However, Apollyon is just one of many toadies in the machine that crushes the rights and freedoms of other human beings under the guise of necessity during wartime:

Who was eligible for La Ferté? Anyone whom the police could find in the lovely country of France (a) who was not guilty of treason, (b) who could not prove that he was not guilty of treason. By treason I refer to any little annoying habits of independent thought or action which en temps de guerre are put in a hole and covered over, with the somewhat naive idea that from their cadavers violets will grow whereof the perfume will delight all good men and true and make such worthy citizens forget their sorrows. (88)

Despite the book’s strong critical success (including such advocates as T.E. Lawrence and F. Scott Fitzgerald), The Enormous Room has faded in popularity. I have no idea why: I’ve read it half a dozen times and never failed to enjoy every single page. It’s a miracle of language, humor, and heart, and one of the best American books of the first half of the 20th century.

It may be that Cummings the poet was simply so overwhelming that he overshadowed everything else:

The Poetry

E.E. Cummings was not only one of America’s most successful poets, but also one of best-loved avant garde poets in any language. The reasons are relatively easy to discern: Cummings’ experimentation can be radical but never inaccessible, and it never fails to be entertaining. This is largely because Cummings’ experimentation is usually visual rather than poetical: as a painter he understood the power of visual presentation, leading to his often jarring arrangement of words and punctuation.

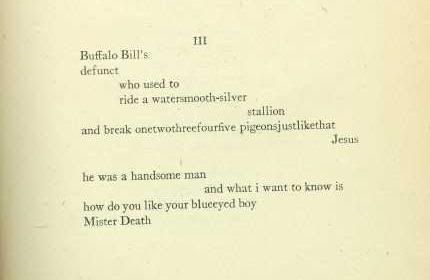

Among the most famous and earliest was “Buffalo Bill’s / defunct” (see image). Note that contrary to popular belief Cummings uses both capitalization and punctuation: the important thing is how he uses it and when he chooses not to.

Among the most famous and earliest was “Buffalo Bill’s / defunct” (see image). Note that contrary to popular belief Cummings uses both capitalization and punctuation: the important thing is how he uses it and when he chooses not to.

Cummings was not the first to recognize the importance of visual presentation in literature, but his experiments are among the best known, from the extended sex-as-driving metaphor of “she being Brand” to the initially unreadable “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r” (it makes sense after you work with it a while).

The disorientation caused by radically unexpected alignments also allows Cummings to slip in some sneaky bits of information for the careful reader, as in the popular “in Just- / spring” (Chansons Innocents), which creates a dizzying joyful portrait of children playing “when the world is puddle-wonderful”, but subtly undercuts it in its epithets for the Balloonman. If you catch the references, the last line suddenly feels sinister.

Cummings’ concerns expressed in The Enormous Room also figure prominently in his poetry, which mocks superficial moralism and facile patriotism, especially when they are used to crush people underfoot:

why talk of beauty what could be more beaut-

iful than those heroic happy dead

who rushed like lions to the roaring slaughter(link)

Again and again, in poems like “i sing of Olaf glad and big“, “the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls“, and “pity this busy monster,manunkind” Cummings shows little tolerance for the idiocies that lead to oppression, war, and hopelessness. “Humanity”, he writes, “i hate you“.

All this would make him a curmudgeonly old misanthrope, except that the single most common topic in his poetry is the reverse: love. Cummings is first and foremost a poet of love, whether of a significant other, of family, or of this stupid race of idiots we’re so wonderfully trapped with:

love is a deeper season

than reason;

my dear one

(in april’s where we’re)(link)

In fact a great deal of his poetry concerns the disorientation of being in love, with the confused syntax and unorthodox spellings allowing the sheer giddiness of love to burst through the prisons of language and grammar. Cummings was sensitive to the relationship between form and theme, and his twisting explorations of grammar and punctuation and alignment are often tied indelibly to the topic at hand.

Along these lines, my personal favorite of all Cummings’ poems is “anyone lived in a pretty how town“, a brief storybook-like lyric about a lifelong love that’s nonetheless heavy with nostalgia and loss. Check out these opening lines:

anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

This is radical even for Cummings: the second line involves a complete dissociation of grammar from meaning. But it’s one of the most beautiful lines Cummings ever wrote, and powerfully sad when it returns unexpectedly later in the poem.

Though I earlier described Cummings as a visual poet, poems like these demand to be read out loud. His singsong, nursery rhyme cadences deepen the portrait of childhood, memory, forgetting, and the inevitable cycles of life. And this very life-ness of life at the center of his artistic work is the reason that Cummings can tackle so many of the concerns that keep the rest of us awake at night, but do so with humor, heart, and humanity.

Further Reading:

- Cummings page at Modern American Poetry: includes bio and links to poems

- Practically all of his poetry at PoemHunter

- E. E. Cummings at kirjasto

- Spring: Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society

- Full text of The Enormous Room

Excerpts taken from The Enormous Room as published by Penguin Classics. Image of Cummings taken from Wikimedia commons (source)

19 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

keep an eye out for the reopening of NION (Never in Our Names), a blog against torture and unjust imprisonment, which is set to reopen with renovations on January 15th.

thank you for reading

“maggie and millie and molly and may

went down to the beach (to play one day)

and maggie discovered a shell that sang

so sweetly she couldn’t remember her troubles,and

milly befriended a stranded star

whose rays five languid fingers were;

and molly was chased by a horrible thing

which raced sideways while blowing bubbles: and

may came home with a smooth round stone

as small as a world and as large as alone.

For whatever we lose(like a you or a me)

it’s always ourselves we find….”

aaaargh! I’m being dragged away by the cummings estate poetry police for posting one of his poems!

Thanks, pico, great diary. My cummings volume is always within reach.

suggest that Cumming’s poetry is only difficult on the surface, and that really he’s very conventional. I wonder if there isn’t — and I’m really just asking your opinion — a bit of snobbery involved there: no one popular could be actually interesting.

But sometimes an artist really is very good despite the fact that everyone says he or she is very good (to be wry about it). Some things are just . . . like that. I wondered what you thought?

profile? He is a sentimental an old fav of mine even though he drifted right ward in his later years. His USA trilogy still stand as a great set of works.

love the self-portrait

i’ve used that, a couple times.

…is my cummings favorite. 🙂