Historical analogies that rely for strength upon generally-held assumptions – often exemplified by a folksy appeal to authority in the form of the phrase, “they say” – carry with them both advantage and disadvantage. The recognition of human nature (“power tends to corrupt…”) does make for convenient shorthand, but as with all generalizations, these little chestnuts also run the risk of imprecision when the discussion goes beyond the super-broad. “They” say, for example, that those who fail to learn from the mistakes of the past are doomed to repeat them, which for an historioranter raises a few interesting questions: What if the circumstances of the times have few, if any, precedent? What if leaders of narrow vision had at their disposal technology that could kill on a scale that had theretofore been unimaginable? What if ideology replaced common sense as a guiding political force?

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll look at the origins of the last war to be called “Great.” Along the way, we’ll encounter nations which based policy around the concept of their peoples’ historical destiny, some guys with great facial hair, and analogies that may fall apart on the micro scale, but get damn scary when looked at through a wider-angle lens.

Today, only three Americans who fought in the First World War are still alive (worldwide, the number is around 20), but already their stories feel nearly as historically remote as the founding of the United States or Napoleon’s mad dash across Europe. It seems almost impossible that someone who fought on the gas-enshrouded no-man’s-lands of France could have ever survived the machine guns, the trenches, and the merciless artillery, much less lived to see the Sopwith Camel become a Stealth fighter – I mean, these are guys who retired during the Johnson Administration, and whose grandkids fought in Korea.

But, as Rimjob reminded us in this week’s snoutful of Totally Irrelevant Crap (specifically, in the excellent Battlestar Galactica update and theorizing), “This has all happened before; it will all happen again.” Indeed, the stage was set for the Great War in the late 19th century, and yours truly isn’t exactly the first person to note the stronger-than-faint whiff of the Gilded Age that’s settled recently over our great nation – but as I mentioned above, analogies can be tricky things. It would be both inappropriate and incorrect to assert that Bush is “just like” Emperor Franz Josef, but conversely, not inaccurate to state that it was Austria-Hungary’s arrogance-based policies that foolishly ignited a conflict both global in scope and vastly out of proportion to the issues that started it.

Geography in a Realpolitck World

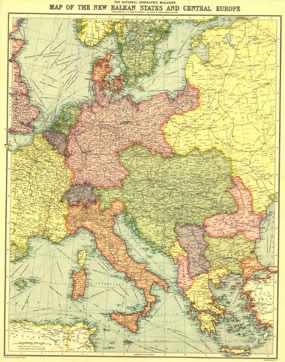

You can look at the map of Europe in 1914 in a couple of different ways. Here’s one:

And here’s another:

Of the two, the latter is probably more reflective of the actual state of affairs than the placid timelessness of the more standard view. At the time, Europe was filled with seething animosities of class and ethnicity, a rising sense of nationalism among various and sundry oppressed peoples, and venerable but tottering empires trying desperately to maintain the supremacy of the previous century’s ways of doing things over the new one’s technology and sensibilities.

Strong believers in a Dickensian industrial and economic model – and in letting unfettered capitalism achieve its equilibrium as an unevenly stratified social pyramid – the leaders of Europe at the turn of the century were forced to look outside their own continent for places to compete. Wars, Campaigns and Operations were waged all over the globe throughout the 1800s, and imperialist leaders occasionally gathered at sickening spectacles like the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 to carve up regions and play God with fates of men and nations. When they were done, the world looked like this:

And yet, despite the occasional native uprising and Partition of Bengal, the major problems facing the European powers lay in their own back yard – with two major exceptions: Spain, which found itself colony-jacked by an upstart Western Hemispheric power that shall remain nameless, and Russia, which was just as soundly defeated by an impertinently rising regional power in Asia. Unluckily for the tsar, Russia was also tied by history and religion to the area of Europe most contested and volatile of all; at odds in the lower right hand corner were Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire in Turkey, and nationalist groups in Serbia and several other Balkan states:

And in the end, of course, the words of Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of Germany from 1862 to 1890, proved prophetic:

“If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some damned silly thing in the Balkans”

That Bismarck should have such an Edgar Cayceish pulse on fighting in Europe makes sense, given that his philosophy of realpolitik is defined by Dictionary.com as Governmental policies based on hard, practical considerations rather than on moral or idealistic concerns. Realpolitik is German for “the politics of reality” and is often applied to the policies of nations that consider only their own interests in dealing with other countries.

Not that any of that has any relevance today, of course.

Historiorant: For all his offensiveness – in both the military and philosophical sense – one has to tip one’s pointy helmet to Otto von Bismarck’s mastery of the soundbite, especially given that he uttered most of these bumper-sticker pearls a decade or two before the car was invented:

“The less people know about how sausages and laws are made, the better they’ll sleep at night.”

“Never believe anything in politics until it has been officially denied.”

“People never lie so much as after a hunt, during a war or before an election.”

“When you say you agree to a thing in principle, you mean that you have not the slightest intention of carrying it out in practice.”

A Blood- and Iron-based Foreign Policy

Otto von Bismarck was in a good position to know the value of unburdening a nation’s policies of moral concerns, since he’d been pursuing such ends-justifying means since the time of the American Civil War. Throughout the 1860s, his conflicts centered around turning a collection of German states nominally under Austrian control into a single German nation under his own king’s thumb – and he used everything from unjustified wars to faked telegrams to achieve it. Since Bismarck was both a Prussian and a member of the aristocratic, warlike Junkers class, it stood to reason (at least in his Rovelike mind) that this new Germany should be unified behind/beneath Prussian leadership, so he first set about collecting up a few north-German states at Austrian expense.

Otto von Bismarck was in a good position to know the value of unburdening a nation’s policies of moral concerns, since he’d been pursuing such ends-justifying means since the time of the American Civil War. Throughout the 1860s, his conflicts centered around turning a collection of German states nominally under Austrian control into a single German nation under his own king’s thumb – and he used everything from unjustified wars to faked telegrams to achieve it. Since Bismarck was both a Prussian and a member of the aristocratic, warlike Junkers class, it stood to reason (at least in his Rovelike mind) that this new Germany should be unified behind/beneath Prussian leadership, so he first set about collecting up a few north-German states at Austrian expense.

Against the wishes of King Wilhelm I, Bismarck engineered a war against Austria over control of the Duchy of Holstein (west of Prussia, just south of Denmark) in 1866. Known as the Seven Weeks’ War, it was a fast and decisive Prussian victory – and one that contained a few odd sidenotes, besides. Once firmly in control of Northern Germany, Bismarck set about finding a way to wrest the southern (and more Catholic) German states from Vienna’s embrace, and as we all so ruefully know, the easiest way to unite a people (if only behind a veneer of nationalism) is to choose a foreign enemy and figure out a way of getting it to “force” you into attacking it.

Bismarck did this by doctoring up a telegram known as the Ems Dispatch, an actual communiqué between Wilhelm I and Bismarck that he’d reworded in such a way as to insult both France and the Germans. Though the original document concerned the slightly-more-esoteric matter of the placement of a Hohenzollern prince on the throne of Spain, Bismarck’s edited version is the one that he released to the press, which obediently fanned the flames that the power-brokers told them to. Five days later, France, to her great misfortune, declared war in a frenzy of Prussian-provoked élan.

The Franco-Prussian War lasted only a few months longer than had the war for Holstein, and when it was over, France was in shambles. In addition to being forced to rethink their earlier confidence in new rifles, the French saw their aging, ailing Emperor Napoleon III – pdf captured in battle and forced to abdicate, as well as enduring the humiliation of seeing the King of Prussia crowned Kaiser of the Germans in the Palace of Versailles (and on Elvis Presley’s future birthday, no less).

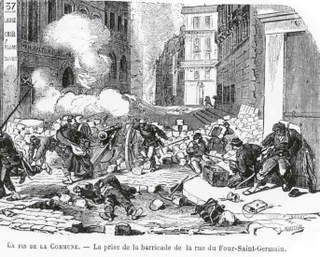

Having taken what they wanted – namely, the coal-rich border regions of Alsace and “quiche” Lorraine and promises of enormous reparations to be paid by France – the Germans departed, leaving a new French president to try to bring his own capital city back under control. Paris had endured an unrelieved siege through much of the winter of 1870-71, and when the postwar government demanded that the city surrender its cannons and swallow the fact that the National Guard would not be receiving promised pay, the people revolted. Taking to barricades and hanging a red flag from the Hotel de Ville, citizens of Paris fought against the French Army as it sought to suppress the Communards; in a week of horrific violence, as many as 30,000 may have been killed, with an equal number arrested – many of these were later deported to places such as New Caledonia in the South Pacific, or simply shot without benefit of a trial.

When Looking in a Mirror is Difficult: The Ascendancy of the Facially Hirsute

Given the similarities in their worldviews, it’s a wonder George W. Bush doesn’t look more like this guy of the left, but then again, your resident historiorantologist could well be off-base in suggesting that the reason King Leopold II had a distinct aversion to the shaving razor was because he couldn’t look at himself in a mirror due to guilt over the way he was running the Congo Free State. Perhaps the King of Belgium was as unconcerned about the atrocities being visited upon the Congolese in the name of “civilizing” them as The Decider is about torture being committed under the U.S. flag – or perhaps wearing elaborate arrangements of thick, virile facial hair was nothing more than the fashion of the age.

Given the similarities in their worldviews, it’s a wonder George W. Bush doesn’t look more like this guy of the left, but then again, your resident historiorantologist could well be off-base in suggesting that the reason King Leopold II had a distinct aversion to the shaving razor was because he couldn’t look at himself in a mirror due to guilt over the way he was running the Congo Free State. Perhaps the King of Belgium was as unconcerned about the atrocities being visited upon the Congolese in the name of “civilizing” them as The Decider is about torture being committed under the U.S. flag – or perhaps wearing elaborate arrangements of thick, virile facial hair was nothing more than the fashion of the age.

Whatever the reason, the treaty tables of the time were surrounded by bristling mustaches, imposing beards, and an pomposity in uniform design that put our own Old Fuss n’ Feathers (from back in 1852) to shame. Together and separately, these men put together an elaborate and fatally flawed system of interlocking and countermanding alliances that obligated nations to certain actions that, once embarked upon, proved unable to be stopped.

Self-centered foreign policies were at the heart of the precarious balance of power. France developed war plans that centered around the recapture of Alsace and Lorraine, while Bismarck and his successors sought to ensure that someone would have Germany’s back in the event that she went to war. To this end, Bismarck arranged for the Three Emperors Treaty between Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany in 1873; it became the Dual Alliance five years later, when Russia bailed for her new bestest friend, France. It was to provisions of this Dual Alliance arrangement that Austria-Hungary appealed in the summer of 1914, in seeking assurances that Germany would go to war on Austria-Hungary’s behalf, should Serbian push result in a Russian shove.

The Dual Alliance technically did have another member, but Italy’s loyalty proved a little more ephemeral than that of the German-speakers to one another. In 1881, Italy (only unified for a little more than a decade itself) became a signatory to the Triple Alliance, which promised mutual aid in the event that one of them was attacked by France. In reality, the treaty was more about keeping Italy from declaring war on Austria-Hungary over territorial disputes in the eastern Alps and along the Adriatic than it was about creating an axis of Central European powers, so Italy saw fit to negotiate a deal-breaker of an agreement on the side.

In secret, Italy concluded an agreement with France that promised aid in the event that the Republique was attacked by Germany. So it was that as the sides were drawn up in the summer of 1914, Italy declared its neutrality on the basis that Germany was waging an “aggressive” war, and the following year entered the conflict on the side of France, Britain, and Russia. Now free to attack their old rival/sometimes-friend Austria-Hungary, they did so, opening a theater that would one day serve as the backdrop for A Farewell to Arms. Romania, which was wedded to Austria-Hungary in a shotgun treaty presided over by Germany in 1883, proved as reliable as Italy, and followed a similar course in determining for which side she would fight.

Bismarck tried to ensure Russian neutrality and avoid the possibility of a two-front war by arranging the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1887, but the document was allowed to lapse by Tsar Nicholas II three years later, around the same time Kaiser Wilhelm II ascended the throne and informed Bismarck that his services were no longer required. With Russo-German relations chilling, the tsar started negotiating in earnest with the French, and in 1892 concluded a treaty in which the signatories promised to come to one another’s aid if any member of the Triple Alliance so much as mobilized against either Russia or France.

Bismarck tried to ensure Russian neutrality and avoid the possibility of a two-front war by arranging the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1887, but the document was allowed to lapse by Tsar Nicholas II three years later, around the same time Kaiser Wilhelm II ascended the throne and informed Bismarck that his services were no longer required. With Russo-German relations chilling, the tsar started negotiating in earnest with the French, and in 1892 concluded a treaty in which the signatories promised to come to one another’s aid if any member of the Triple Alliance so much as mobilized against either Russia or France.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Once upon a time, nations did not raise or maintain enormous armies unless they had actually declared war. This quaint convention kept countries from having to pay for militaries standing on war footings during peacetime and compelled leaders to avoid the temptation to use force as an extension of diplomacy, but was deemed absurd in the mid-20th century.

From Splendidly Isolated to Dreading Nought

Victoria’s Britain had deigned to involve itself in the tangled affairs of the continent, preferring instead to fight numerous wars on the fringes of their colonial possessions. In the late 1890s, she was awakened to the growing danger of Germany’s seeking of a place in the sun when the Royal Navy began to notice that there were other people’s battleships floating around on the high seas. That Germany embarked upon a naval arms race with Britain was due largely to the offices of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who served as the Kaiser’s Secretary of State of the Imperial Navy Department beginning in 1897. He would later serve as Grand Admiral (1911) and Commander of the German Navy (1914).

His massive expansion of the German fleet also served to light a fire under some British shipbuilding butts. In 1902, Britain concluded a treaty of alliance with Japan, so as to thwart German ambitions in the East, and in 1906, launched H.M.S. Dreadnought, the first in an entirely new class of battleship. By the time of the war, Britain was floating 49 battleships to Germany’s 29.

In 1904 and 1907, Britain delved into the European alliance system by signing “Cordial” agreements with France and Russia, respectively. While not obligating the British to take up arms in defense of its friends, the Entente did have the effect of placing a “moral obligation” on London once the armies started mobilizing (a 1912 treaty promised British protection of the French coast from German attack in exchange for French defense of the Suez Canal). Add to this the British regard for an 1839 treaty that promised British aid if “little Belgium’s” neutrality were ever violated – Germany was urging the Brits to disregard the Belgian treaty as a “scrap of paper” – and you have all the makings of an armed intervention.

War and More War

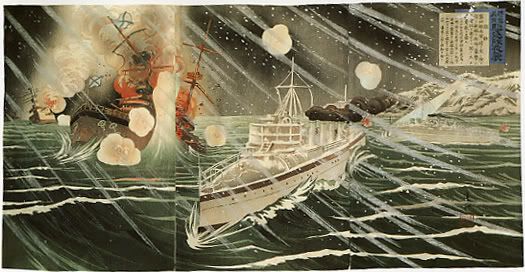

In 1904, Japan joined the Colony Game by punching the Russians hard in the face. Approaching the Russian ships anchored at Port Arthur (Lushun, China), on the evening of February 8, launching a surprise torpedo attack that left the Russians at a disadvantage in the land invasion that followed (actually, only 3 of the 16 torpedoes launched by the Japanese actually hit something and exploded as designed, but those 3 were the important ones – they cost Russia the use of two battleships and a cruiser). The Russo-Japanese War lasted until September of the following year, and saw Japan take hold of Korea and Manchuria. The stunning Japanese victory at the Battle of Tsushima Strait in May, 1905, sealed Russia’s fate; by the end of the year, Teddy Roosevelt was earning himself a Nobel Peace Prize by adjudicating a treaty that protected Russia from the worst of potential outcomes while simultaneously denying Japan the fruits of what it considered an honestly-won victory.

Presiding over a nation whose armed forces are getting their asses kicked is never easy, and Tsar Nicholas II was no exception. The Russian Revolution of 1905 had a lot to do with frustration at battlefield losses, as well as with an antiquated economic system, but it did provide a few tangible results. Nicholas was obligated to establish a legislative assembly called the Duma, but as things turned out, he had about as much patience for listening to the people’s representatives as does George W. Bush, and his autocratic rule continued unabated after a brief flirtation with semi-democracy.

Other results of the failed revolt took the form of the 50 or so worker’s soviets that were established in St. Petersburg and elsewhere, and the revolutionary cred earned by some of the guys (like Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky) who would be back for a second round. Desperate to restore a semblance of prestige to Mother Russia, the tsar became more and more ensnared in the volatile Balkans, where Russia’s Slavic brethren were engaged in all sorts of struggles with the Austrians, the Ottomans, and the Italians.

Italy decided Libya was ripe for the picking in 1911, and engage the Ottomans in a short, sharp war that saw the world’s first bombardment by aircraft and cost the sultan possession of Libya, Rhodes, and the Dodecanese Islands. Turkey lost Crete and the rest of its European possessions by the 1913, after Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro started fighting over borders and the major powers were forced to apply a diplomatic band-aid to what had long been an open sore.

Turkey still had a few more punches to take, however: Later in 1913, Bulgaria attacked its former allies over control of parts of Macedonia, even as an influential group of Ottoman officers known as the “Young Turks” issued a call for reform within the Sick Man Empire. Taken out of context, their demands (first issued in 1908) were not all that unreasonable; many would be implemented in full force by the post-war Turkish government of Kemal Ataturk.

9. Every citizen will enjoy complete liberty and equality, regardless of nationality or religion, and be submitted to the same obligations. All Ottomans, being equal before the law as regards rights and duties relative to the State, are eligible for government posts, according to their individual capacity and their education. Non-Muslims will be equally liable to the military law.

10. The free exercise of the religious privileges which have been accorded to different nationalities will remain intact.

11. The reorganization and distribution of the State forces, on land as well as on sea, will be undertaken in accordance with the political and geographical situation of the country, taking into account the integrity of the other European powers.

14. Provided that the property rights of landholders are not infringed upon (for such rights must be respected and must remain intact, according to law), it will be proposed that peasants be permitted to acquire land, and they will be accorded means to borrow money at a moderate rate.

16. Education will be free…

While the other Balkan states were beating back the Bulgarians – Romania occupied the capital of Sofia during the summer – Turkey sallied forth and recaptured Adrianople. Peace followed the Bulgarian surrender, but it was a tense peace, in which nationalistic Balkanites vied for self-determination and a unique voice under the wing of their Pan-Slavic brethren in Russia.

Little Things Turn Into Big Things

Emperor Franz Josef didn’t even like his heir-to-be, Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand – the guy had married a woman of insufficient nobility back around the turn of the century, leading the old Austro-Hungarian ruler to declare that the crown would not pass from Franz Ferdinand to any child he might create with his beloved wife Sofie. Still, he was going to get to be emperor himself, so he did those things that emperors-to-be did: attend suares, funerals, and reviews of troops. This last duty was what brought he and Sophie to Sarajevo in June, 1914 (vintage video through this link).

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand on June 14th is worthy of a diary in its own right – as is the Rasputin-plagued intrigues of the Russian court, and a thousand other events of this era – so let us leave all talk of conspiracy theory behind, and concentrate on how the circumstances of the Archduke’s death were perceived by those involved, especially Austria-Hungary. In point of fact, however, the assassination was seen as an opportunity for advancement in more capitals than just Vienna.

Franz Josef’s ministers thought they had enough evidence in hand to implicate the Serbian government with involvement in the assassination. Seizing upon the chance to restore some normalcy via the tried-and-true method of beating up on a neighbor, Austria’s formal response – issued three weeks after the deed – prompted the British Foreign Secretary to confess that he had

never before seen one State address to another independent State a document of so formidable a character.

Reading the document, it’s easy to see why even a foreign service vet would cringe:

Serbia is forced to admit culpability in the assassination and to admit to being behind every evil that had ever plagued Austria-Hungary, then…

The Royal Serbian Government shall further undertake:

(1) To suppress any publication which incites to hatred and contempt of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the general tendency of which is directed against its territorial integrity;

(2) To dissolve immediately the society styled “Narodna Odbrana,” to confiscate all its means of propaganda, and to proceed in the same manner against other societies and their branches in Serbia which engage in propaganda against the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The Royal Government shall take the necessary measures to prevent the societies dissolved from continuing their activity under another name and form;

(3) To eliminate without delay from public instruction in Serbia, both as regards the teaching body and also as regards the methods of instruction, everything that serves, or might serve, to foment the propaganda against Austria-Hungary;

(4) To remove from the military service, and from the administration in general, all officers and functionaries guilty of propaganda against the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy whose names and deeds the Austro-Hungarian Government reserve to themselves the right of communicating to the Royal Government;

(5) To accept the collaboration in Serbia of representatives of the Austro-Hungarian Government for the suppression of the subversive movement directed against the territorial integrity of the Monarchy

and so on; photo is King Peter of Serbia

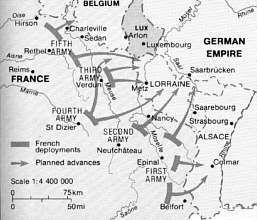

With the brinksmanship afoot, both sides scrambled for their moldering old treaties and started calling in their alliance-favors. Serbia sought protection under Russia’s wing, while Austria-Hungary turned to Germany. Russia’s ally, France, saw this as a potential chance to justifiably launch an assault against Germany (with the objective being a quick liberation of Alsace and Lorraine and to restore some dignity after the 1870 humiliation), and so didn’t try to talk the tsar back from the edge.

Ironically, it was the Kaiser of Germany who did. The “Willy-Nicky” Telegrams between Wilhelm II and the tsar reflect an almost jocular tone at first, then get darker as the inevitable transpires and the two leaders (who were actually closely related) find themselves bound by treaty to go to war with one another. The Germans were reasonably confident they could win a short, decisive war – they had secret plans, in place since 1905, that would ensure France would be knocked out of a two-front war early on, allowing Germany to turn its troops around in plenty of time to face the slow-mobilizing Russian juggernaut – so when Austria asked for reassurance that Germany still had her back, Berlin replied with what’s often called a ‘Blank Cheque’.

So it was that on July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Three days later, Russia began mobilizing its forces in support of its small ally, which also triggered a timetable in Berlin that required quick action if Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan was to work. Russia’s mobilization – which Germany estimated would take six weeks – gave Germany the excuse she needed to declare war on Russia, which she did on August 1. Two days later, Germany declared war on France, and the following day sought to implement the Schlieffen Plan by invading Belgium en route to attacking Paris from the north, even as their left flank held against the French charges called for by the pie-in-the-sky Plan XVII. To wit:

“The will to conquer is the first condition of victory.”

“Offensive to the maximum!”

“Offensive without hesitation!”

“The offensive alone leads to positive results.”

Enemies who through themselves at machine gun nests in the name of élan were expected, but for all the planning they’d done, what the Germans had failed to take into consideration was that Britain might be less beholden to realpolitik than they otherwise appeared. Indeed, rather than take the pragmatic course of neutrality and aloofness, the British dusted off the 1839 “scrap of paper” and committed British honor to the battlefield, declaring war on Germany shortly after “little Belgium’s” neutrality had been violated. They arrived on the continent just in time to stand on the French left flank and stop the Germans at the First Battle of the Marne – a critical divergence from the Schlieffen Plan by Chief of Staff Helmut von Moltke may have played a role in this halting of the German advance, too. (a cool set of animated maps is available at PBS.org’s The Great War)

Historiorant:

The deadline approacheth, and obviously, there’s a lot more to tell – guess the mechanics of first great battles of the Great War will have to wait for another bat-night. In the meantime, let’s think about what analogies can be found between the years leading up to the Great War and our own current day.

The deadline approacheth, and obviously, there’s a lot more to tell – guess the mechanics of first great battles of the Great War will have to wait for another bat-night. In the meantime, let’s think about what analogies can be found between the years leading up to the Great War and our own current day.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, and DocuDharma.

8 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

… or perhaps the colonies have been adulterating the coffee coming in to my little eastern port.

Can we have a cliff-side note? History is not my strong suit … though I do not-half-bad at finding patterns in nature, and Nature’s beast: Man. Can I implore you to underline those analogous things whose analogosity klangs the bell of meaningfulness for those for whom History is, indeed, a strong suit: studied, understood, dealt, played — or does that devolve to churlishness, like asking a poet to diagram a couplet?

Did the Iraq oil war started in the ‘teens of the last century? http://www.indybay.org/newsite…

Look for Robert Newman’s History of Oil video on YouTube – hilarious and frightening.

fascinating, and aggravating. The analogy seems to me to be that the United States’ entry into WWI was based in good part on phonied-up information, and decided by a choice few white men, committing thousands of American soldiers to war.

because she didn’t do it. “Deign” is to do something from a high perch, often holding one’s nose.

My father was an officer in the 9th Hussars, a British Cavalry regiment, graduate of Sandhurst, served in India as well as France in the Great War. During WW2 he was commandant of the local Home Guard and presided over an Italian prisoner of war camp, filled with very happy Italians who worked the land while the british Pommies were off to war. My step-father served in north Africa in the desert operations where Rommel ruled for a while. A cousin was in the Kenya Police during the Mau Mau times. So, war is not distant at all for many of us.

The Vietnam war was on many of our doorsteps even if we were too young we lost mothers and fathers, sons and daughters and many friends, their pain in many cases still live with us. I had a phonecall on Thanksgiving from a Vietnam Vet friend who had just returned from a stint as a contractor security guard in iraq. He now lives in Southeast Asia. My American ancestors fought in the Revolutionary war, the War of 1812 and the Civil War, so war is not nearly as distant as one might think and learning not to repeat mistakes is always a good thing.

Until we learn to break the chains of destructive behaviour we shall inevitably repeat them. So reading and writing and talking about the seeds of war is always a good thing in my very huumble opinion anyway. War is never history, or herstory, War is OURSTORY.