On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967

On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967

A few days ago, coincidentally on Martin Luther King Jr.’s real birthday, I was at a gathering of middling size where I only knew two people. While I sipped my club soda and nearly nodded off listening to someone buzz on and on about football, a conversation cluster within eavesdropping distance took up the subject of reservation casinos. I live in California and four Indian gaming referenda will appear on the ballot February 5, so a discussion of the topic was not a surprise. I’ve always had an (apparently inborn) ability to tune into conversations across a room while blocking out those in front of me, and my interest was piqued because whoever was explaining the gaming proposals seemed to know quite a bit about the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that led to these measures being put before the voters. Then I heard it. Somebody said, “It’s the redskins’ revenge.”

For the first time, I looked over that way, and all five people in the group were gently laughing or smiling or nodding assent.

I don’t think he meant it maliciously. Quite possibly he even thought he was being supportive. It’s doubtful he would have said “nigger” or “wetback” or “chink,” since there were African Americans, Asian Americans and Latinos in the room. But no obvious Indians. Because I don’t wear feathers, mocassins or a loincloth and can pass for white, he apparently felt unconstrained in making what I’m sure he thought was a harmless little joke. Maybe even a pro-Indian joke. I could have walked over and explained how infuriating what he had said was, how hurtful it was that everybody seemed to have enjoyed what he said. But it gets so bloody tiring dealing with the reactions. Not just the accusations of “political correctness,” the rolled eyes or the “Aren’t you being too sensitive?” charges, inevitably delivered with a smile. But also the downward glances, the stammering, or even the apologies that so often greet an objection: “Oh, I’m sorry. I know that you … uh… Native Americans object to that.”

As if it’s okay to deploy a slur when no member of the slurred ethnicity is around to be insulted? As if racism only matters to people of color? As if every one of us is not harmed to the core by such talk about any ethnicity and should object to it?

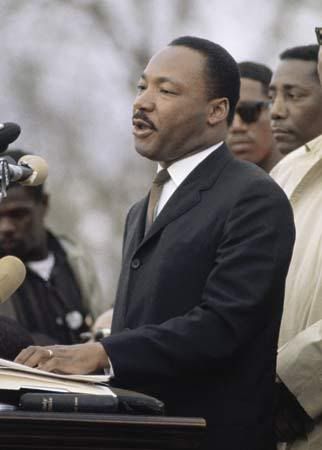

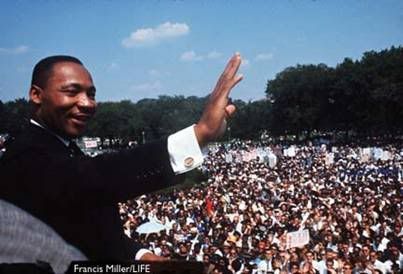

This incident – I can recount a dozen others I’ve witnessed in the 21st Century – made me ponder a great deal the theme I’ve heard so much of recently, on-line and off, that race and racism have been transcended in America. That we no longer need to talk about these matters because, well, because talking about them only engenders bad feelings about something that is fixed except in a few backward locales by people who will be dead soon anyway. That, 45 years after the summer day Reverend King made that soaring speech on the Washington Mall, his dream is wholly achieved.

Nobody can deny that tremendous progress has been made. Progress that is a testament both to the message of universal legal equality in the nation’s founding document and two centuries of fierce and costly struggle by people of color and their white allies to transform that message into reality. A testament to people’s willingness to change themselves, to surrender their prejudices and fears, to recognize injustice and do something about it, even to give up their lives if that’s what it takes. That progress cannot be sneered at. It reflects an America and Americans of all colors at their best.

Racism nonetheless remains a chronic influence in our lives. Yet many white people say they don’t want to talk about race. They say they’re sick of talking about it. That stuff is all in the past, they say, and wonder aloud why we can’t talk about something else. I think what most are really saying is that they don’t want to listen to talk about race.

On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967

On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967