Would-be imperialists beware: You gotta be careful when you go to pick a fight with a country possessed of a 5000-year history, for such a nation will inevitably have in its historical record an example of every kind of victory and every kind of loss, and every kind of human triumph and failing in between. In these countries, ideas like a Declaration of Human Rights aren’t imports; they’re the original products of ancestors and fellow countrymen. Been through a few golden ages, followed by periods of decline and ruin? Check. Dealt with foreign aggressors and internal revolt? Check. Been led by people that history remembers as “the Great,” as well as by guys so incompetent that they make George W. Bush look adequate? Check.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll take a look at Persia in the Classical Age – and find out that Iran’s willingness (and ability) to go toe-to-toe with the West’s greatest superpowers is not something that first emerged in the Era of Petroleum. As a courtesy to the neo-imps among us, I should give fair warning: We may also find that the Iranian contemporaries of Rome influenced the makings of our modern world far more than might first seem apparent.

Historiorant: The original Persia series was posted shortly after I started posting on DKos, in February and March, 2006, and wound up consisting of seven diaries that were considerably shorter (and less illustrated) than the present incarnation of a History for Kossacks piece. Accordingly, I’ve decided to commemorate the occasion of my anniversary with a navel-gazing ceremony, retrofitting some of these earlier diaries into the format that evolved in their wake – such was the case with the episode from two Sundays ago, Ancient Persia.

Apologies for last week’s hiatus, btw: early in the evening, I was unable to divert my attention from my beloved New England Patriots, and afterwards, I was preoccupied with bemoaning their fate and rending my garments. – u.m.

Ride of the Horse Archers

When last we gathered for an historiorant, a particularly ambitious (and blithely arrogant) Roman named Crassus had just led tens of thousands of men to their doom in The Imperial Surge of 53 BCE. The people who slaughtered the Romans on the dusty plain of Carrhae (in extreme southeastern Turkey) were the Parthians, descendents of the semi-nomadic Parni tribe that had migrated from their homeland east of the Caspian Sea and adopted many of the ways of the people they found already living in the region of Parthia (northern Iran). The blending of military styles, in particular, made the Parthian 2.0 no slouch on the battlefield; expanding behind armies of highly disciplined horse archers and heavily armored cataphract knights, the Parthians at one point (ca. 100 BCE) dominated an area stretching from Armenia to the borders of India.

When last we gathered for an historiorant, a particularly ambitious (and blithely arrogant) Roman named Crassus had just led tens of thousands of men to their doom in The Imperial Surge of 53 BCE. The people who slaughtered the Romans on the dusty plain of Carrhae (in extreme southeastern Turkey) were the Parthians, descendents of the semi-nomadic Parni tribe that had migrated from their homeland east of the Caspian Sea and adopted many of the ways of the people they found already living in the region of Parthia (northern Iran). The blending of military styles, in particular, made the Parthian 2.0 no slouch on the battlefield; expanding behind armies of highly disciplined horse archers and heavily armored cataphract knights, the Parthians at one point (ca. 100 BCE) dominated an area stretching from Armenia to the borders of India.

In time, the Parthians came to think of themselves as the bloodline-bona fide rulers of Persia, claiming descent from Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358 BCE), and by extension, from Cyrus the Great himself. Basing themselves south of the Caspian Sea and north of the Alborz Mountains, the Parthians created themselves a reborn Achaemenid Dynasty (the line of Cyrus, Darius, and Xerxes from three centuries before), though some aspects of their culture were a bit Hellenistic in flavor owing to the Seleucids – courtiers spoke Persian and wrote in the Pahlavi script, but Greek was used on coins until the 2rd century CE – whose 150-year hold on power was weakening around the same time as the Parthians were growing in strength.

The Parthian Dynasty (246 BCE-224 CE) – sometimes called the Arsacid, after one of its founders – established its main capitol at Ctesiphon, just across the river from Seleucia on the Tigris (south of Baghdad, on the west bank); from there, the horsemen proceeded to carve up the prostrate empire of the Seleucids. Under Mithradates (Mehrdad) I (171-138 BCE) and especially under Mithradates II (124-87 BCE), who defeated the Scythians (for a time) and added Armenia to the Parthian domain, the horsemen established an empire that basically defined the eastern edge of Rome’s sway. Though the next 300 years saw parts of Mesopotamia occasionally fall to the Parthians, and Ctesiphon to the Romans three times in the 1st century CE alone (Armenia went back and forth), the Parthians remained strong enough to keep the borders of Rome at the west bank of the Tigris (more or less), where the forts and garrisons the Romans were obligated to maintain proved a constant and costly drain on the resources of the Eternal City.

Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BCE, as potrayed by a 7th century CE mural

The Parthians fought along their northern borders, as well, eventually capturing several important cities along the Silk Road. This did two things in particular: it cut off from Western contact Greco-Bactria, the last remaining Hellenistic kingdom in Central Asia, and it brought Iran into almost exclusive contact with China. It seems the Chinese took a shine to Parthian horses – in the late 2nd century BCE, explorer/conquistador Zhang Qian first brought back word to the Han emperors that there were “Heavenly Horses” to be found on the Iranian Plateau; later he arranged for a trade pact between Parthia and China. By the first century CE, Han cavalry was composed largely of Parthian horses, and their battle tactics showed signs (like a modified Parthian shot) of Persian influence. Some Chinese took a shine to another import from Parthia, as well: around 148 CE, a Parthian nobleman/Bhuddhist missionary (the Bamiyan-Buddha-carving Kushan Empire was Parthia’s next-door neighbor to the East) named An Shih Kao established temples around the Han capital of Luoyang, and went on to make the first translations of Buddhist scripture into Chinese.

Weird Historical Sidenote: The Chinese thought very highly indeed of Parthian horses – I’m told another name for them, “Soulun,” translates to “vegetarian dragon.” There’s also a rumor that the horses sweated blood, but stories like that (especially the 2000-year-old ones) are notoriously difficult to verify. Something that is a little easier to establish is that the Scythians dug Parthian horses, too – but usually just the chestnuts and bays. So it is that the Russian Don breed (est. 18th c. CE) preferred by the Cossacks often shows similar coloration even today.

Weird Historical Sidenote: The Chinese thought very highly indeed of Parthian horses – I’m told another name for them, “Soulun,” translates to “vegetarian dragon.” There’s also a rumor that the horses sweated blood, but stories like that (especially the 2000-year-old ones) are notoriously difficult to verify. Something that is a little easier to establish is that the Scythians dug Parthian horses, too – but usually just the chestnuts and bays. So it is that the Russian Don breed (est. 18th c. CE) preferred by the Cossacks often shows similar coloration even today.

Weird Historio-Political Parallel: The silk for which Rome was willing to pay dearly had to pass through the lands of a mortal enemy first, and the only reason that enemy didn’t cut off trade entirely was that their own economy became increasingly dependent upon the commodity. For the life of me, I can’t think of a single modern parallel to this situation – can you?

The Parthian governmental system was comprised of up to 18 vassal states and a Royal Council of 5 client kings with significant authority to check the power of their liege – the Suren clan, for example, had exclusive crowning rights. The decentralized nature of their government both helped and hurt the Parthians: they could (and did) survive multiple falls of their capital by simply relocating, but like all feudal systems, conflicts resulted when lords began to acquire power that rivaled that of the king. Such was the case in the early 3rd century CE, when the descendents of a priest named Sassan began dethroning and usurping other local lords in the region of Persis (a/k/a Pars; southern Iran).

An Empire of the Old School

Persia proper lay within the domain of the Parthians, but it was administered in the now-traditional satrap-based form of feudalism practiced in this region since Cyrus handed out his first political favor. Like all feudal systems, the Persian satraps had to constantly be wary of the local lords and chieftains who administered the various districts within their satrapy, as a feudal lord’s strength is only as great as the sum of his loyal vassals. Turns out that this general rule applied to the Parthians, only they didn’t realize it until it was too late.

In 224 CE, Papak (alternate spellings abound), a village leader and the son of Sassan, a priest of the Temple of Anahita, managed to dethrone Artabatus V, ruler of Persia. As Persia was a vassal state to Parthia, this might have caused little concern in Ctesiphon had the ongoing feudal obligations – the ass-kissing, the tax-paying – been met, but neither Papak nor the son who succeeded him, Ardashir, was the sort of guy to content himself with paying tribute to an overlord (actually, Ardashir had an older brother, named Shapur, who probably ascended the throne around 220 CE, but it seems a building collapsed upon him in 222 – u.m.)

For Parthia, the ensuing war was as short as its results were bad; Ctesiphon fell in 226 CE, and the Sassanids assumed the rulership of the empire. They saw themselves as a culture native to Persia, and like the Parthians before them, sought to legitimize their dynasty by claiming descent from the legendary Achaemenian line of Cyrus and Xerxes. From their own past they grabbed the title Shahanshah (“King of Kings)”, and they established their capital upon the site of ancient Gor (modern-day Firouzabad, in southern Iran), which had been destroyed by an Alexander the Great-engineered flood – Ardashir had a tunnel dug through a mountain to drain the lake that still remained.

Historiorant: As I mentioned above, I’m trying to compress those seven earlier diaries into four, so it really doesn’t behoove me to be chasing after every shiny historical tidbit that appears along our route, but every once in while, your resident historiorantologist runs into one he can’t help but share. Such is the case with Ardashir, founder of the Sassanid Empire – though I’m shortly going to blaze through four hundred years of their rule in just a few paragraphs, the story of their founder is simply too colorful to ignore. It’s also quite a work of court history, and will no doubt serve as an invaluable resource after the Bush misadministration is gone and historiogrovelers (the sworn enemy of the historioranter) like Fances Fukuyama seek to tortuously justify the stupid assertions they made at the onset of the Era of Compassionate Conservatism.

The army of the Worm, which had been inside the fortress, completely marched out, and zealously and vehemently struggled and fought with Ardashir’s troops, many being killed on both sides. When the army of the Worm came out (of the fortress), it took such a by-road that it became impossible for any of Ardashir’s troops to go out (of the camp) or to bring in any food for himself or fodder for his horses, and, (consequently), the satiety of all men and animals was changed into want of food and helplessness.

When Mitrok, son of Anoshepat, an inhabitant of Zarham in Pars, heard that Ardashir was without provision near the capital of the Worm, and obtained no victory over its army; he accoutered his troops and heroes, marched towards the residence of Ardashir, and carried away all the wealth and riches of Ardashir’s treasure.

Ardashir, hearing of such violation on the part of Mitrok and other men of Pars, reflected upon it for a while thus: “I ought to postpone the battle with the Worm, and [then] go to fight out a battle with Mitrok.” He, (therefore), summoned all his forces back to his quarters, deliberated with their commanders, (first) sought the means of delivering himself and his army, and then sat himself down to eat breakfast.

That very moment a long arrow, dispatched from the fortress, came down and pierced, as far as its feathers, through the (roasted) lamb that was on the table.

On the arrow it was written as follows: “This arrow is darted by the troops of the lord of the glorious Worm; we ought not to kill a great man like you, so we have struck that (roasted) lamb,” Ardashir, having observed the state of things, disencamped his army and withdrew from the place.

The army of the Worm hastened after Ardashir, and hemmed in his men again in such a manner that Ardashir’s army could not proceed further. So Ardashir [himself] passed [lit. dashed] away singly by the sea-coast.

The Kârnâmag î Ardashîr î Babagân (‘Book of the Deeds of Ardashir son of Babag’), Chapter 6

Weird Historical Sidenote: Great story about that “army of the Worm” thing. Seems that once upon time, a maiden found a kerm (“worm”) in an apple, and made a pledge to feed and care for it. Since it just so happened to be a lucky worm, this turned out to be a really good decision: soon her father conquered the entire province, which became known as Kerman, or “Worm Province.” The family’s luck held until Ardashir realized that the worm was their Achilles’ Heel, so to speak, and…well, I gotta let The Glory of the Shia World (pub. 1910) and its source, whom the authors describe as no less than the greatest epic poet ever, tell the rest of it:

Consequently he (Ardashir) resolved on a daring stratagem, and, disguising himself as a merchant prince, he presented himself before Haftan Bokht (the King of Kerman) and said, that as he owed all his success in trade to the good fortune of the Worm, he requested the honour of feeding it for three days. This petition was readily granted, and as Firdausi, the greatest epic poet of all the cycles of time, writes:

When their souls were deep steeped in the wine-cup;

Forth fared the Prince with his hosts of the hamlet,

Brought with him copper and brazen cauldron,

Kindled a flaming fire in the white daylight.

So to the Worm at its meal-time was measured

In place of milk and rice much molten metal.

Unto its trench he brought that liquid copper;

Soft from the trench its head the Worm upraised.

Then they beheld its tongue, like brazen cymbal,

Thrust forth to take its food as was its custom.

Into its open jaws that molten metal

Poured he, while, in the trench, helpless the Worm writhed;

Crashed from its throat the sound of fierce explosion,

Such that the trench and whole fort fell a-quaking.

Swift as the wind Ardeshir and his comrades

Hastened with drawn swords, arrows, and maces.

Of the Worm’s warders, wrapped in their wine-sleep,

Not one escaped alive from their fierce onslaught.

Then from the Castle-keep raised he the smoke-wreaths

Which his success should tell to his captains.

Hasting to Shahr-gir swift came the sentry,

Crying, “King Ardeshir his task hath finished!”

Quickly the captain then came with his squadrons,

Leading his mail-clad men unto the King’s aid.

And in the name of all that’s holy, please, please: nobody tell President Bush that the key to conquering Iran lies in finding a gigantic, enchanted worm and pouring molten copper down its throat.

Despite the grandiosity of the title adopted by Sassanid rulers, “king of kings” accurately describes their government, which followed the same basically feudal format as the preceding three Iranian empires. Their aristocracy was an amalgamation of earlier history, too, with nobility comprised of a mix of the leaders of old Parthian clans, Persian aristocratic families, and nobles from subjected territories. The Sassanids imposed a 4-tiered caste system of Priests, Warriors, Secretaries, and Commoners, and sought actively to eradicate Greek influence in Iranian culture. Ardashir, especially, recognized the potent weapon that faith mixed with national pride can be, and he wasn’t afraid to play favorites: Zoroastrianism was made the state religion, the Magi were given special privilege, and more than a few marble friezes show Ahuramazda, the supreme deity as spaken of by Zarathustra, conferring the authority to rule upon Ardashir.

The religious fervor of the Sassanids had, as religious fervors tend to, a darker side. . Run-of-the-pew Christians were periodically persecuted – a situation that became worse after Rome converted to Christianity and its practice in the Sassanid Empire became an act of treason. Still, for most of their 4-century reign, the Sassanids practiced religious toleration, bringing their Zoroastrian faith with them as they established trading colonies as far away as India, Vietnam, and Malaysia; other exports include the Cult of Mithras to Rome, where it competed for converts with the early Christians. A notable exception to the general rule of tolerance was made in the case of the prophet Mani,

…who claimed to be both Christ and the Buddha, and was crucified, (ca. 236 CE). Mani preached a Zoroastrian conflict between good and evil, but then (like the Gnostics) regarded matter as evil. Served by a celibate and vegetarian priesthood, Manicheanism spread both East and West. To the East, it was adopted by the Sogdians and Uighurs (under Bugug Khan, 759-780), until the advent of Islâm, and spread all the way to China. Marco Polo’s description of a Christian community in China which had actually forgot it was Christian may actually refer to a group of Manicheans.

Manicheanism headed West, too, where elements of it can be seen in the religion of the Cathars of southwestern France, whose unique culture and civilization were pretty much wiped out by a deliberate act of genocide emanating from Rome in the early 13th century.

The Crossroads of Classical Geopolitics

There’s not much left of Ctesiphon, the largest city in the world in the 6th century. Located about 35 km south of Baghdad, people were still fighting one another on the site 14 centuries later: in 1915, the British and Ottomans engaged in a pitched battle amongst the ruins, destroying much of what little remained.

From their position astride the Silk Road, the Sassanids did a masterful job of allowing plenty of trade goods, but precious little knowledge, to pass between Rome and China. They also enriched themselves as middlemen, and availed themselves of all the scientific, cultural, and technological benefits that can accrue to a nexus of world trade. It was during the Sassanid period that close contact with India brought in stories that would eventually find their way into the Thousand Nights and One Night, and there is speculation that the 90-foot spiral Zoroastrian fire altar at Ardashir’s new capital was the basis for the design of the Spiral Minaret at the Great Mosque of Samarra. Domestically, the Sassanids were aggressive builders who actively sought to reinvigorate traditional Persian art forms, and cities like Gundishapur, where a university was founded in the 4th century, were among the greatest centers of learning of their time. As for architecture, the great historiodeity Will Durrant says:

“Sasanian art exported its forms and motifs eastward into India, Turkestan, and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt, and Spain. Probably its influence helped to change the emphasis in Greek art from classic representation to Byzantine ornament, and in Latin Christian art from wooden ceilings to brick or stone vaults and domes and buttressed walls.”

Being a neighbor of the Roman Empire wasn’t easy for anyone who had the pleasure, but the Sassanids began drawing lines in the sand in the earliest days of their power. Ardashir’s son Shapur antagonized the Romans even further than his father had, by demanding that they relinquish all their territories in Asia – presumably so that the title “King of all Iran and non-Iran” would better fit the new Sassanid ruler – then swiftly invading Mesopotamia. His initial victories were reversed in 243 CE, but the following year, the young emperor Gordian III opened the doors of the Temple of Janus – signifying that Rome was now at war; they’d been closed since 70 CE – for the last time in Roman history, and personally led a disastrous troop surge down the Euphrates. Since I don’t want to be accused of mongering conspiracies, I’ll defer to Wikipedia for some tidbits on the death of the emperor:

Being a neighbor of the Roman Empire wasn’t easy for anyone who had the pleasure, but the Sassanids began drawing lines in the sand in the earliest days of their power. Ardashir’s son Shapur antagonized the Romans even further than his father had, by demanding that they relinquish all their territories in Asia – presumably so that the title “King of all Iran and non-Iran” would better fit the new Sassanid ruler – then swiftly invading Mesopotamia. His initial victories were reversed in 243 CE, but the following year, the young emperor Gordian III opened the doors of the Temple of Janus – signifying that Rome was now at war; they’d been closed since 70 CE – for the last time in Roman history, and personally led a disastrous troop surge down the Euphrates. Since I don’t want to be accused of mongering conspiracies, I’ll defer to Wikipedia for some tidbits on the death of the emperor:

Persian sources claim that a battle was fought (Battle of Misiche) near modern Fallujah (Iraq) and resulted in a major Roman defeat and the death of Gordian III. Roman sources do not mention this battle and suggest that Gordian died far away, upstream of the Euphrates. Although ancient sources often described Philip, who succeeded Gordian as emperor, as having murdered Gordian at Zaitha (Qalat es Salihiyah), the cause of Gordian’s death is unknown.

Philip the Arab (r. 244-249 CE), the Praetorian Prefect (recently ascended to his office following the mysterious death of his predecessor), quickly grabbed up the purple robes of the emperor’s office, bought off Shapur to the tune of 500,000 denari (he also left behind bunch of legionaries, who were enslaved and compelled to build the city of Bishapur to commemorate the guy who had beaten them), and headed back to Rome to secure his claim in the Senate. Despite Philip’s promise of future payments, Shapur soon resumed the war by looting Antioch – which provoked another Mesopotamian troop surge that would end with the first-ever capture of a Roman Emperor in battle.

In 253 CE, Valerian was named Emperor, and he spent the next seven years flitting about the imperial borders, putting out fires where he could. There were Marcomans in the Alps, Visigoths in Thrace, and Sassanids in Syria – and Valerian tried to deal with them all. So it was that in 260 CE, he found himself in Edessa as a Sassanid army surrounded the city. Though he had liberated Antioch (and captured Shapur’s harem at one point), things did not turn out so well for Emperor Valerian: he was taken prisoner by Shapur in late 259 or 260 CE, and died without ever again tasting freedom or seeing Rome. Sources vary as to his treatment – some have Valerian being used as a footstool before getting the molten-gold-down-the-gullet treatment, while others say he and his men lived in passable conditions, considering that they’d been enslaved for hard labor, in Bishapur.

In 253 CE, Valerian was named Emperor, and he spent the next seven years flitting about the imperial borders, putting out fires where he could. There were Marcomans in the Alps, Visigoths in Thrace, and Sassanids in Syria – and Valerian tried to deal with them all. So it was that in 260 CE, he found himself in Edessa as a Sassanid army surrounded the city. Though he had liberated Antioch (and captured Shapur’s harem at one point), things did not turn out so well for Emperor Valerian: he was taken prisoner by Shapur in late 259 or 260 CE, and died without ever again tasting freedom or seeing Rome. Sources vary as to his treatment – some have Valerian being used as a footstool before getting the molten-gold-down-the-gullet treatment, while others say he and his men lived in passable conditions, considering that they’d been enslaved for hard labor, in Bishapur.

Shapur was also busy in the east. He expanded into the Kabul river valley, captured Peshawar, and carried a sacred relic – the Begging-Bowl of the Buddha – back to Istakhr. His son, Shapur II, expanded the empire to the borders of China, then invaded Arabia, prior to settling in for a nice long conflict with the Romans. As one of very few civilizations to whose ruler the Emperor addressed letters “My Brother,” the Sassanids were a constant threat on Rome’s eastern flank, and over time, their military made adjustments to its composition and tactics based on the Persian threat. The addition of heavily-armored cavalry, for example, was inspired by the cataphracts of Persia – and Roman heavy cavalry is part of what inspired the later development of the European mounted knight.

It Was (mostly) Fun While It Lasted

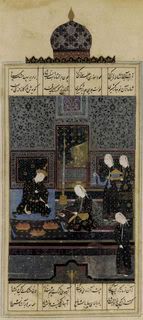

Bahram Gur and the Indian princess in the black pavilion from a Khamsa (Quintet) by Nizami mid 16th century Safavid dynasty. (Wikipedia Commons)

Bahram Gur and the Indian princess in the black pavilion from a Khamsa (Quintet) by Nizami mid 16th century Safavid dynasty. (Wikipedia Commons)

For three centuries, the Sassanids and Rome parried, with the former enjoying no fewer than two golden ages while the latter succumbed to the inevitable forces of decline and fall. Notable leaders during this long span of time include Bahram V (421-438 CE), who was to go on to enjoy national epic hero status as the lover and hunter Bahram Gur, and Khorsow I (531-579 CE) a/k/a Khosrow Anushirvan (the Just). Treatment of the adherents of non-Zoroastrian faiths varied by ruler, as did the fortunes of war and trade, but the stability imposed the caste system generally helped the subjects of the empire ride out the reign of the occasional poor leader; when the end finally came, it did so during a precipitous quarter-century that saw virtually all of the empires of antiquity knocked back on their heels.

The final war between Rome – now reborn as Byzantium – and Persia started when the Sassanid king (and gargantuan dome-builder; see Ctesiphon pics above) Khosrow II (r. 591-628 CE) invaded Syria and sacked Jerusalem in 614 CE. It is said the Jews there welcomed the Persians, remembering the stories of the wise and merciful Cyrus, and because the Christians in the city were persecuting them. It is also said that the Sassanids carried back to Persia another sacred relic – the True Cross – as plunder from Jerusalem (they give it back in a generation or two). Khosrow went on to take over Egypt and the islands of Cyprus and Rhodes, and even besieged Constantinople for a time, but the slow-moving Byzantine army retaliated forcefully in 627 CE, cutting a broad juggernaut-type swath of destruction through Mesopotamia. Weary of being led by a megalomaniac and humiliated by the advance of Byzantine forces deep into Sassanid territory, the Persian army mutinied and murdered Khosrow in 628 CE.

Notice the dates? Now check them against your Hegira calendar.

After being decisively spanked by the Byzantines, not to mention having their ruler assassinated by his own army, the Sassanids fell into chaos and disunion. They ran through a dozen kings in the last twenty years of the empire, but this was just one of many symptoms of social and economic decline that were ultimately rooted in the vast power of the Zoroastrian state religion. Its rigid system of social stratification was beginning to strain under the weight of taxation – more favors to the priests and the powerful than could be paid for by the plebians – and the common folk were starting to resent the burden. Additionally, since persecution of non-Zoroastrians was sanctioned by the state, the empire could always be counted upon to produce a small-but-virulent undercurrent of seething resentment, just waiting for an opportunity to erupt into rebellion. And finally, that old Persian problem of freedom-minded satraps started cropping up again – the Lakhmids were only the first to assert their independence after the assassination of Khorsow II in 628 CE; other vassal states on the periphery soon followed.

Historiorant:

The original thought was to get all the way through the arrival of Islam in Persia, leaving off at the rise of the Abbasid Dynasty, but that version of the diary wound up at 15 single-spaced pages without pictures. That’s a little long, even by my standards – but I gotta think a story like that of Ardashir and the Worm is worth delaying a discussion on the Battle of al-Qadissiyah by a week or so.

The original thought was to get all the way through the arrival of Islam in Persia, leaving off at the rise of the Abbasid Dynasty, but that version of the diary wound up at 15 single-spaced pages without pictures. That’s a little long, even by my standards – but I gotta think a story like that of Ardashir and the Worm is worth delaying a discussion on the Battle of al-Qadissiyah by a week or so.

Next up, then, will be Islam and Medieval Persia; for this week, let’s try’n think of some of the other non-Roman cultures of Classical Antiquity that our Dear Leader has spurned in his tortured interpretation of the historical record – what’s the most critical thing he hasn’t learned about Han China or Mauryan and Gupta India?, for example. If that seems a little esoteric, then how about this: Had he attended a university whose history professors had sufficient integrity to ensure that he actually earned his degree through study and effort, what lessons about the Parthians and the Sassanids might now be able to inform Bush’s decision-making with regard to Iran?

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

9 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

that’re strewn along the trail – otherwise, this supposed compaction of the series is gonna wind up more like an expansion…

The ultimate pony diary….vegetarian dragons no less!

Thanks!

And I really loved the part about the silk trade. Nah, I can’t think of any lubricating commodity whose trade poses a similar situation. Not at all.

…I didn’t mean to upstage your piece. I forgot that dang li’l checkbox again.

:/