At the conclusion of our last historiorant, we left off with the Sassanids in pretty dire straits. It was 636 CE, little more than a decade after they had had their sasses handed to them by the Byzantines in a series of battles across Mesopotamia, and only four years removed from the passing of the Prophet Muhammad. Now fierce men bearing the star and crescent had appeared on the Euphrates; to Yazdgerd III, the last Zoroastrian king of the Persians, fell the task of defending Ctesiphon and the gateway to Iran.

So join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, for a look at the beginnings of a clash of civilizations that continues to the present day, as well as the many Iranian contributions to what would become known as Islam’s Golden Age. Along the way, we’ll also be taking a contextual side-trip to the Founding of Islam – but only after pausing to read the sign about how, imho, we should be approaching historiographic minefields.

Historiorant: For the past few weeks, I’ve been updating, re-vamping, and re-publishing the first series I ever did on DKos – to judge by the number of comments received, a pretty obscure one – which was comprised of seven diaries on Persia/Iran. Even at that early date, I wasn’t entirely unaware that I was climbing out onto some controversial historical branches in a forest filled with erudite folks in possession of a great deal more specialized knowledge than I, so I took the precaution of explaining my approach to the historical arts at the beginning of the part 3. Alas, since that particular diary has the dubious distinction of generating the lowest number of comments of any I’ve written, I’m not really sure the message resonated.

Thus, I’ve decided for tonight’s episode to leave in a bit of editorializing that I’d earlier thought to remove. Some of what follows was quoted (by me) in a comment last week, responding to a comment regarding the spelling of Iranian names – in the end, it seemed appropriate to keep the reiteration of historiorantological policy in place as we enter one of those parts of history wherein disagreements over how the story is told can result in everything from ill feelings to war.

Historical Ethics and Controversial Topics – skip ahead if you want to get straight to the narrative

Before we get started, let me be up front about a few things: I’m not a Muslim, nor Iranian, nor of any ancestry or creed related to what I am about to report – and while I’m on a confessional kick, I might as well state that my area of historical expertise is not Ancient Mesopotamia, nor Islam, nor theology. I am an American of European descent and left/libertarian politics, and so carry with me the inevitable biases that that particular combination of cultures is bound to impart. Ostensibly, my history degree should also serve as proof that I have gained at least some skill in BS detection and differentiation, insofar as such skills are applied in the historiographic arts, and that I’ve learned how to assemble a narrative from disparate sources. You’ll just have to take my word that I’m of a personality that seeks to level playing fields and to approach with integrity every project and job I take on, even when following the rules (of debate, or of decorum) works against me.

As an historian, the idea is to transcend all that negative stuff to the greatest degree possible: the task is to gather available data, assess it critically with an historian’s eye, and write down what most closely approximates the truth of what happened. For guidance in approaching controversial topics like the one I’m about to go into, I always like to refer to the Greek writer Lucian of Samosata (ca. 125-ca.180 CE), who had the cajones to entitle a book, How History Should Be Written:

The historian should be fearless and incorruptible; a man of independence, loving frankness and truth; one who, as the poet says, calls a fig a fig and a spade a spade. He should yield to neither hatred nor affection, but should be unsparing and unpitying. He should be neither shy nor deprecating, but an impartial judge, giving each side all it deserves but no more. He should know in his writings no country and no city; he should bow to no authority and acknowledge no king. He should never consider what this or that man will think, but should state the facts as they really occurred.

In Last Week’s Episode…

In 636 CE, the Sassanid Empire extended to the Euphrates River, which formed a natural border on the western frontier – in modern terms, this means that much of what is now eastern Iraq was traditionally Persian land. This is also the reason why some of the key events in the history of Iran and Shi’a Islam actually occur in Iraq, and why that country factors so prominently in the story of how a Zoroastrian people became Muslim.

The Sassanid Empire at its height, during the reign of Khosrow II around 610 CE.

After being decisively spanked by the Byzantines, and having their ruler assassinated by his own army, the Sassanids fell into chaos and disunion. They ran through a dozen kings (and even a couple of queens) in the last twenty years of the empire, but this was just one of many symptoms of social and economic decline that were ultimately rooted in the vast power of the Zoroastrian state religion. Its rigid system of social stratification was beginning to strain under the weight of taxation – more favors to the priests and the powerful than could be paid for by the plebians – and the common folk were starting to resent the burden. Additionally, since persecution of non-Zoroastrians was sanctioned by the state, the empire could always be counted upon to produce a small-but-virulent undercurrent of seething resentment, just waiting for an opportunity to erupt into rebellion. And finally, that old Persian problem of freedom-minded satraps started cropping up again; the Lakhmids were only the first to assert their independence after the assassination of Khorsow II in 628 – this wasn’t wholly unexpected; they’d tried to convert to Christianity, and paid dearly for it, while Khorsow was still alive – and other vassal states on the periphery soon followed.

Meanwhile, down in the Arabian desert…

The Prophet Muhammad led his followers on the Hijrah from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE. Since this is event which separates once-and-for-all the umma (community) from those who had rejected the Prophet’s word, the hijrah also marks the start of the year 1 A.H. (anno hegira), and the first day of the Islamic calendar. Six years later, after a couple of important battles that I’ll have to detail in some future diary – and in the same year as the assassination of Khorsow – Muhammad decided to return to Mecca for a peaceful pilgrimage.

Since he’d also decided to bring around 1500 friends with him, the Meccans thought it best to stop Muhammad at the border. There they concluded a treaty which forbade that year’s pilgrimage, but promised to permit one after a one-year cessation of hostilities. The peace held for two years, but when the Meccans violated its terms, Muhammad gathered a force said to number 10,000, including both the Muhajirun (“those that made the Hijrah” or “Emigrants”) and the Ansar (“Helpers”; converts gained in Medina) and took the city without a fight. It was at this point that Muhammad entered the Ka’bah, a pagan temple and object of pilgrimage since time immemorial, and smashed the idols contained within; the act impressed ‘Amr ibn al-‘As, who had the conquest of Egypt in his future, and Khalid ibn al-Walid, the “Sword of God”-to-be, enough that they swore their allegiance to Islam, and set about organizing its rapid expansion. Muhammad died two years later, in 632 CE, the same year the Yazdgerd III ascended the throne of the Sassanids.

Muhammad’s father-in-law, Abu Bakr, became the first Khalifa (“Successor”; anglicized as “caliph”) of the Muslim community after Muhammad’s death, but the succession was not without controversy. According to Shi’a tradition, Muhammad publicly proclaimed his successor to be Ali, husband of the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, at a place called Ghadir Khumm. The subsequent appointment of Abu Bakr to the leadership position was denounced by the shi’at ‘Ali, or “Partisans (or Party) of Ali,” as a conspiracy between Abu Bakr and Umar, another of Muhammad’s companions and a later caliph. Sunnis, who trace their heritage through the dynasties which grew out of Abu Bakr’s line of caliphs, hold fast to the fact that Abu Bakr’s position was freely and duly conferred by the leadership of the community. Though they do honor the descendents of Muhammad, Sunnis do not concur with the Shiite assertion that the rightful leaders of the faith are those related by blood to the Prophet.

Abu Bakr spent the two years of his reign subduing rebel Arabian tribes in a series of small battles which came to be known as the Ridda Wars. He then launched a Muslim invasion of Syria and Palestine as a means of consolidating all the Arabic peoples under one Islamic banner – and in the process became a devastating wildcard in the neverending border wars between the Byzantines and Sassanid Persia. They began butting heads with the Persians early on: In 633 CE, as part of a campaign to bring the recently-independent Lakhmid Arabs into the fold, the Muslims began taking small border towns along the west bank of the Euphrates. They marched against the Sassanids in earnest in 634 CE, but were repelled in a tumultuous fight that came to be known as the Battle of the Bridge.

Every silver lining’s got a touch of grey

They were overeager, those Arabs on the western bank of the Euphrates, near modern-day Kufa, Iraq. The Persian camp lay on the other side of the river, and the Muslim general Abu Ubaid thought he might be able to surprise them if he were able to build a bridge of boats and get his army across before being detected. Over the protestations of his advisors, he ordered the bridge built in a single night, and over it his troops surged.

It didn’t work out. Sassanid general Bahman (Mardan Shah) had his men put their elephants at the head of the army, which spooked the horses of the Arab cavalry. This left the Muslim leadership exposed, and subsequently martyred, as the Sassanid infantry advanced. The Muslims were trapped with their backs to the Euphrates, and the day turned into a rout as they tried to flee en masse back across the boat bridge. They lost two-thirds of their 9000-man force that day, and were vulnerable in a way that they would never be again. Bahman should have pursued and attacked, but he couldn’t – at the very moment of victory, he received an urgent summons to return to Istakhr to put down yet another revolt.

It didn’t work out. Sassanid general Bahman (Mardan Shah) had his men put their elephants at the head of the army, which spooked the horses of the Arab cavalry. This left the Muslim leadership exposed, and subsequently martyred, as the Sassanid infantry advanced. The Muslims were trapped with their backs to the Euphrates, and the day turned into a rout as they tried to flee en masse back across the boat bridge. They lost two-thirds of their 9000-man force that day, and were vulnerable in a way that they would never be again. Bahman should have pursued and attacked, but he couldn’t – at the very moment of victory, he received an urgent summons to return to Istakhr to put down yet another revolt.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Though not the guy pictured with the great helmet (he’s an unidentified figure from the 5th-7th centuries, located in the Louvre), nor the general who led the Sassanids to victory at the Battle of the Bridge – indeed, he’s likely the person who issued Bahram’s last-minute retreat orders – Rostam Farrokhz?d (sorry about the Wikipedia link; there’s not a whole lot out there out there in English on Rostam, who is apparently a prominent figure in some Iranian nationalist circles) is an important military and political figure during this period. Ethnically Persian, he was born into Sassanid aristocracy in Armenia and ascended to the Satrapy of Azerbaijan and Khorassan (nowadays eastern Iran; in ancient times, a significant chunk of Central Asia) when Azarmidokht, one of the post-Khorsow II queens, not only rebuffed a marriage proposal from his father, but had him killed for asking. In revenge, Rostam marched on Ctesiphon, where he blinded and deposed the queen. A couple of years later, after seizing Armenia back from the Byzantines, he got involved in internal Sassanid politics in a big way: together with a brother and an ally, he seems to have been part of a triumvirate formed to support young Yazdgerd in facing the ever-mounting foreign and domestic threats to Persia.

Arab spirits revived when they – with the help of a fortuitous sandstorm – defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Yarmuk (in Syria) in 636 CE, and now-caliph Umar felt comfortable shifting his forces east to reopen hostilities with the Sassanids. At nearly the same time, a Muslim army of indeterminate size (though definitely smaller than the reputed 100,000 on the Persian side) again approached the area of Hilla (specifically, al-Q?disiyyah) on the banks of the Euphrates, but this time it would be over-eagerness on the Sassanid side that would lose the battle. And this time, the attacker would pursue his retreating foe.

Operation Enduring Motif

Rather than waging a defensive war on the east bank of the Euphrates, Rostam, now in personal command of the army, this time crossed over to the Arab side, hoping to crush the smaller force before backup could arrive from Syria. For two days, the Persian elephants wreaked havoc among the Muslim cavalry, and it looked like all might be lost for the foot soldier, too, but on the third day, the Arabs turned the tables on the elephants: they costumed their horses in such a way as to terrify the huge beasts, and when a soldier managed to kill the lead elephant, the other pachyderms panicked, turned, and trampled their way through the Persian army. As the desperately-awaited Syrian troops began to arrive, the Arabs decided to press their advantage, and continued to advance even after night fell; the resultant clashes in the darkness gave the attack its name: “Night of Clangor.”

As the day broke, a sandstorm blew up from behind the Muslims and straight into the faces of the Sassanids. The Muslim commander, Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, ordered his army forward, and the Persian center collapsed in response. Rostam, caught up in the disorganized retreat, was captured and beheaded by a Muslim soldier as he tried to swim to safety across a canal. The soldier, Hil?l ibn `Ullafah by some accounts, is reported to have held the severed head aloft before the Persian soldiers, shouting, “By the Lord of the Ka’bah! I have killed Rostam!” It was enough to turn the battle into a rout, and though a few Zoroastrians converted to save their skins, most of the Sassanid army that went to Al-Qadisiyyah died there as infidels in the eyes of the victors. From that day forward, those Muslims who had fought in the great victory were accorded privileged status in Iraq and, especially, in its garrison at al-Kufah. Veterans of the battle were thereafter known as ahl-al-Qadisiyyah – kind of like adding “fought at Normandy” to a WWII vet’s legal name.

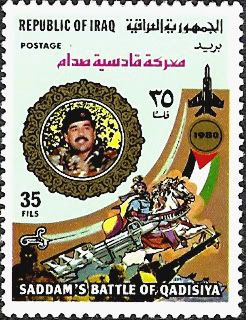

The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah has enormous significance in the Arab world – everything from a public square in Libya to a city in Kuwait to a university in Jordan bear its name. It probably doesn’t come as any surprise, but Iraqis hold this memory especially close: they named a province after the battle, and a neighborhood in Baghdad, and a host of schools and clubs. Remember that big cross-sword sculpture that arches over that road in Baghdad? It has two names: “Hands of Victory” and “The Sword of Al-Qadisiyyah.” Saddam built it 1989. He also had images of the battle printed on Iraqi money, murals of himself surveying the battle (along with some tanks) painted across a swath of cityscape, and said this about the then-upcoming Iran-Iraq War:

The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah has enormous significance in the Arab world – everything from a public square in Libya to a city in Kuwait to a university in Jordan bear its name. It probably doesn’t come as any surprise, but Iraqis hold this memory especially close: they named a province after the battle, and a neighborhood in Baghdad, and a host of schools and clubs. Remember that big cross-sword sculpture that arches over that road in Baghdad? It has two names: “Hands of Victory” and “The Sword of Al-Qadisiyyah.” Saddam built it 1989. He also had images of the battle printed on Iraqi money, murals of himself surveying the battle (along with some tanks) painted across a swath of cityscape, and said this about the then-upcoming Iran-Iraq War:

In your name, brothers, and on behalf of the Iraqis and Arabs everywhere we tell those [Persian] cowards and dwarfs who try to avenge Al-Qadisiyah that the spirit of Al-Qadisiyah as well as the blood and honor of the people of Al-Qadisiyah who carried the message on their spearheads are greater than their attempts.

From an April, 1980 speech; excerpted in Religion, Ethnicity and Identity Politics in the Persian Gulf (PDF)

Zoroastrian Persia extinguished

There was a token siege of Ctesiphon before Yadzgerd fled and the Arabs sacked the city. The Sassanids marched eastward, the Muslims in hot pursuit, before turning to launch a major counterattack at Jalula. The ploy was unsuccessful; the Persians were again defeated. Though there were a handful of unsuccessful engagements in Mesopotamia afterwards, Yazdgerd and the bulk of what remained of the Sassanid army retreated east of the Zagros, onto the Iranian Plateau.

Caliph Umar initially felt that the feet of the Zagros would make an excellent border while he consolidated and garrisoned the new lands he had recently acquired, even desiring at one point a “wall of fire” to separate the two empires (interesting choice of metaphor, from a Zoroastrian point of view), but he soon started hearing compelling rationales for continuing the invasion. His generals argued that Yazdgerd, safe behind his mountain barrier, would rebuild an army, while his political advisors warned of the rebel-inducing effect in the newly-conquered territories of allowing any Persian government to survive. Finally, he had a lot of soldiers who were expecting to be paid in land at the end of the campaign, and most of the non-desert land in Mesopotamia was already spoken for.

This and many other very cool satellite maps available vie Petrie, Cameron (2005), ‘Exploring Routes and Plains in Southwest Iran’, ArchAtlas, January 2008, Edition 3, http://www.archatlas.org/Petri… Accessed: 18 February 2008.

This and many other very cool satellite maps available vie Petrie, Cameron (2005), ‘Exploring Routes and Plains in Southwest Iran’, ArchAtlas, January 2008, Edition 3, http://www.archatlas.org/Petri… Accessed: 18 February 2008.

Umar gave in to the pressure and authorized an attack across the Zagros. In 641 CE, at Nihavand (60 km south of Hamadan, Iran), Yazdgerd made one final stand in defense of his dynasty. Again the Sassanids faced the general ibn-Abi-Waqqas, and again the great cavalryman led the star and crescent to victory. His empire shattered, Yazdgerd spent nearly ten years as a fugitive before being captured and executed in the city of Merv in 651 CE. For centuries thereafter, the eastern border of the Caliphate lay in Afghanistan, Transoxania, and the Sind region of India to the west bank of the Indus. By 674 CE, the last vestiges of the Sassanid Empire – heirs to Parthians, heirs to the Seleucids, heirs to the Achaemenians – had fallen under Muslim control. About the only remnant of Yazdgerd’s rule still around today is the Zoroastrian calendar (the Wikipedia article is pretty good), which marks time counting from the year he ascended the throne.

What Seems Clear

The conquering Muslims took steps to ensure that their soldiers and settlers didn’t “go local.” Intermarriage with non-Arabs was forbidden, troops were kept in garrison towns rather than on out-of-sight/out-of-mind estates, and Muslims were forbidden from learning the language and literature of those they had vanquished. They were not averse, however, to incorporating much of the Persian governmental structure, and the ancient Persian systems of court etiquette and imperial administration were adopted by the Arabs, who had previously had little need of either. These customs and courtesies would be learned by Europeans through interactions with Muslims in North Africa and Spain, and the establishment of Outremer during the Crusades, and in so doing became the ancestor of the diplomacy of Versailles and the courtly manners of St. Petersburg (among many others).

Non-Muslims were placed in a separate category for taxation, and were subject to restrictions regarding cultural displays, but they were not forced to convert to Islam. As for Zoroastrians, the relatively-neutral, but dangerously unsourced, Wikipedia entry says:

Muhammad, the Islamic prophet, had made it clear that the “People of the Book”, Jews and Christians, were to be tolerated so long as they submitted to Muslim rule. It was at first unclear as to whether or not the Sassanid state religion, Zoroastrianism, was entitled to the same tolerance. Some Arab commanders destroyed Zoroastrian shrines and prohibited Zoroastrian worship; others tolerated the native Persian beliefs. After some dispute, Zoroastrians were accepted as People of the Book. Some authorities identified them as the mysterious Sabeans mentioned in the Qur’an and thus entitled to tolerance.

The Sabeans were actually from Yemen, and exercised dominance over the southern Red Sea from the 19th- to the 7th centuries BCE – u.m.

Many of these dhimmi (“people of the pact of protection”) did convert, but the pace was much faster in the cities than in the rural areas. The majority of Iran was not converted until the 9th century, and Shi’a Islam, with which Iran is so intimately associated today, did not become the state religion until the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th century.

For their part, Zoroastrian refugees moved eastward during the time their status as dhimmis was being settled, while others followed in the centuries afterward. A large community settled in Gujarat (northwestern India), and Mumbai, where they became known as the Parsi. Their organizational skills quickly proved valuable; though only a fraction of the whole Indian population, the Parsis made some advantageous early agreements with the British that led to wealth and power so disproportionate to their numbers that even Gandhi commented on it. In the same breath, he also notes the generosity of Parsi philanthropy, calling it “perhaps unequalled and certainly unsurpassed” – and that was years before the one of the more noteworthy Parsis of the 20th century, Freddie Mercury (nee Farrokh Bulsara) was even born.

Traditional Zoroastrian faith faces a lot of challenges in the contemporary world, not the least of which is an unwillingness to accept converts. This, coupled with a commonly-held, very conservative interpretation of just who among their own is eligible to undergo a critical initiation ceremony, has resulted in diminishing numbers – there are currently estimated to “at most 200,000” Zoroastrians worldwide. The major concentration is still in India, where nearly 70,000 Parsis represented .006% of the Indian populace in a 1996 census (when it falls below .002%, estimated to occur around 2020, they’ll get reclassified from “community” to “tribe”). Finally, the traditional method of disposing of the bodies of their dead – placing them on the Towers of Silence for birds to consume – is running afoul of modern sensibilities (and views from nearby high-rise apartments).

Now for the (other) Controversial Bit

The subject of how Islam came to Iran is a matter of heated debate among scholars of that part of the world, and a lot of the issues are inseparable from such dissention-causers as nationalism, ethic pride, and religion. Here I will try to present a couple of different views, and ask the reader to make his or her own determination about whether Islam came to Iran in the form of mass epiphany or at the point of a sword.

From a source about 3 centuries removed:

“The residents of Bukhara became Muslims. But they renounced [Islam] each time the Arabs turned back. Qutayba b. Muslim made them Muslim three times, [but] they renounced [Islam] again and became nonbelievers. The fourth time, Qutayba waged war, seized the city, and established Islam after considerable strife….They espoused Islam overtly but practiced idolatry in secret.”

Tarikh-i Bukhara, via Wikipedia

From a relatively neutral source:

Many Persians submitted to the invaders when the Arabs demanded less taxes than the Sassanids had, and did not force conversion to Islam. Later, Islam did spread to non-Arab groups, most notably the Persians, who began to convert in significant numbers as Islamic rule over Persia strengthened in the centuries after the initial conquest. However, the Sassanid Empire played a major role in developing a distinct Persian nationalism, which survived the Islamic conquest and mass conversion of Persians to Islam. The Persians and the Arabs would become the leading ethnic groups in the Islamic world, and each soon realised that their cooperation was fundamental to the survival of the empire.

From the Institute for the Secularization of Islamic Society:

Nothing could be further from the truth than to imagine that the dhimmis enjoyed a secure and stable status permanently and definitively acquired — that they were forever protected and lived happily ever after.

From a pro-Iranian source:

The shuubiyya literary controversy of the ninth through the eleventh centuries, in which Arabs and Iranians each lauded their own and denigrated the other’s cultural traits, suggests the survival of a certain sense of distinct Iranian identity. In the ninth century, the emergence of more purely Iranian ruling dynasties witnessed the revival of the Persian language, enriched by Arabic loanwords and using the Arabic script, and of Persian literature.

And a link to, but no quote from, a really pro-Iranian source: click here if you wish, but don’t say you weren’t warned that doing so may well cause a little red light to flash on somewhere in the bowels of Fort Meade.

Regardless of the interpretation of its means and ends, the empire which adopted these Iranian traditions and structures was the Abbasid, the founding of which is the stuff of another diary entry. Suffice to say that when they came to power in 750 CE, the Abbasids moved the capitol of the Caliphate to the newly-constructed city of Baghdad, only 20 or so miles away from burned-out Ctesiphon, and subsequently experienced a golden age of culture and learning.

Historiorant:

Sorry about not getting this up at the regular bat-time last night; the weekend got too busy, and the subject matter too delicate, for a hurried job of simply reposting the earlier piece. On a somewhat less auspicious note (given my thought of trying to combine those seven original diaries into four) is that this one covered only the same period as the version from two years ago, only it took four more pages to do it – so apologies, brevity-fans; this “condensing” of the earlier series may wind up equaling it in length.

Next week: The Abbasids, a smattering of short-lived but nevertheless influential regional kingdoms, and the establishment of state Shi’aism under the powerful Safavid Dynasty. For now, perhaps we can discuss some of the other times in history in which two powers, locked in a titanic, mutually-depleting struggle, never saw coming the threat from some hitherto-unnoticed third player.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

Sorry about the day-lateness of this one; adminigods, feel free to shuffle/demote/whatever if this messes up any schedules.

Thanks for this snapshot of history and culture. Well done.

This period of History in this part of the world I’ve never known much about (Euro historian here). The Indo-European wanderings I know, but I don’t pick up the thread again for this region until the Crusades.

Maybe when life calms down I’ll start working on my history studies again.

Namaste!

Still love it, here or in orange. Excellent job.

and a whole lotta research. Thanks.

As it happens, this ties in, I think, with a new book I just saw reviewed and intend to read soon. God’s Crucible: Islam and the Making of Europe, 570-1215, by David Levering Lewis.

He is, you may know, the twice-Pulitizer-winning biographer of W.E.B. DuBois. And a very readable writer for an academic, doesn’t load his pages down with impenetrable verbiage.