When last we looked in on the history of Iran, the dust of Battle of al-Quadissiyah was just settling, and Zoroastrian Persia had fallen under the dominion of the armies of Islam. As she has done with every other of her would-be conquerors, however, the culture of the conquered soon became inexorably tied to that of the new overlords; from Persian minds sprang some of the greatest achievements of the Golden Age of Islam. Even gold won’t glitter forever, though, and the forces of time and history exerted themselves on a succession of kingdoms and dynasties for several centuries before one proved strong enough to make the unification thing stick.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, for a whirlwind tour of nearly 1000 years of Iranian history, from the Abbasids to the Safavids, by way of the Ziyarids, if you will – plus an important announcement (he said grandiosely) from your resident historiorantologist.

Historiorant: For the past few weeks, I’ve been celebrating my two-year anniversary at DKos with a re-visitation of the first series I published here, a seven-parter on Iran/Persia. So far, there have been three diaries in the review – Ancient Persia, Classical Persia, and Islam Comes to Persia. Regular Sunday-night visitors to the Cave may have missed that last one, as it went up about 24 hours later than my regular bat-time.

Alas, the intersection of job responsibilities (and the real world in general) that caused the delay last week have not abated, nor does it seem like they will any time soon – for some reason, the third quarter of the high school year always seems the hardest on teachers as well as students. That being the case, I’m afraid I’m going to have to announce the shuttering of the Cave of the Moonbat for about a month or so, and plan on returning at the end of March with the remainder of the Persia series.

This isn’t a GBCW; it’s a hiatus, similar to the one pico announced for the Literature for Kossacks series not long ago. I’d be all for maintaining the continuity of posting an HfK every Sunday night while I’m enduring self-imposed semi-lurkerhood, so if any history-types out there would like the keys to the Cave for a guest-hosting gig, please drop me a line – e-mail addy’s on my userpage. Til’ then, enjoy the Primary Wars, and I’ll look forward to grubbing my way back to TU status in a few weeks.

A Little Political Stage-Setting

If there’s one thing that history – both ancient and very recent – shows, it’s that succession issues can cause real problems. Last week’s episode highlighted some of the events surrounding the establishment of Shiism shortly after Muhammad’s death in 632 CE; this week, a major part of the story surrounds the political ramifications of more leadership choices made by the earliest Muslims. Some of those ramifications have proven long-lasting indeed: many of those centers of pilgrimage and Shi’a holy sites that keep getting blown up in Iraq trace their importance to the years immediately following the assassination of Ali, the last of the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs.

They were called “Rightly-Guided” because they had all known Muhammad himself, and were among his earliest and closest companions; as for the other part:

The word ‘Caliph’ is the English form of the Arabic word ‘Khalifa,’ which is short for Khalifatu Rasulil-lah. The latter expression means Successor to the Messenger of God, the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be on him). The title ‘Khalifatu Rasulil-lah’. was first used for Abu Bakr, who was elected head of the Muslim community after the death of the Prophet.

Abu Bakr’s caliphate (632-634 CE) was short but significant; it was he who ensured that those tribes that renounced Islam following the Prophet’s death were brought back into the fold. Abu Bakr also began scuffling with the Byzantines in places like Syria, and probed the Sassanid defenses along the Euphrates. Just before he died, he issued a pretty sensible code of conduct for the Muslim army to follow as it burst forth from Arabia:

“Do not be deserters, nor be guilty of disobedience. Do not kill an old man, a woman or a child. Do not injure date palms and do not cut down fruit trees. Do not slaughter any sheep or cows or camels except for food. You will encounter persons who spend their lives in monasteries. Leave them alone and do not molest them.”

Umar, an early convert (there’s a…well, a story behind this, but I’m going to exercise historioranter’s discretion and table any discussion of it to the comments – u.m.) whose influential status in pre-conversion Mecca was a morale-booster for the community, became Abu Bakr’s successor. This was appropriate, in a sense, as it had been Umar’s gesture of support for Abu Bakr that had resulted in the vote going in favor of the latter; in another sense, however, it resulted in “Corrupt Bargain”-type criticism from the Shi’at Ali, who favored leadership based on relation to Muhammad (Ali was married to Muhammad’s daughter, Fatima). Umar’s caliphate (634-644 CE) saw enormous expansion of Muslim holdings, with his armies defeating Byzantines, Sassanids, and locals from Afghanistan to the shores of North Africa before he was assassinated by a “Magian” – a Zoroastrian. It is said that Umar thanked God before he died that his killer had not been a Muslim.

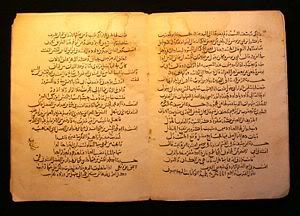

The third Rightly-Guided Caliph was Uthman, a scion of the Umaya clan, from the same Quraish tribe as Muhammad, who had been of the Hashim clan. Technically, the vote that put him into the office made Uthman the first Umayyad caliph, but since he never named an heir, he isn’t considered the founder of the dynasty that followed his successor. The first six years of his caliphate (644-656 CE) are notable for his compilation of the Qur’an, but things started going poorly for him in the last half of his reign. Various conspiracies arose against him, until finally, after being besieged within his own house in Medina, rebels slipped over the back wall and beat him to death while he was reading the Qur’an (the one in the pic may have Uthman’s blood upon it’s pages).

The third Rightly-Guided Caliph was Uthman, a scion of the Umaya clan, from the same Quraish tribe as Muhammad, who had been of the Hashim clan. Technically, the vote that put him into the office made Uthman the first Umayyad caliph, but since he never named an heir, he isn’t considered the founder of the dynasty that followed his successor. The first six years of his caliphate (644-656 CE) are notable for his compilation of the Qur’an, but things started going poorly for him in the last half of his reign. Various conspiracies arose against him, until finally, after being besieged within his own house in Medina, rebels slipped over the back wall and beat him to death while he was reading the Qur’an (the one in the pic may have Uthman’s blood upon it’s pages).

Ali, the related-by-marriage early contender for the caliphate, now ascended to the office of caliph, but his reign (656-651 CE) would be marred by civil war. His supporters had been among the most vocal of the anti-Uthmanists, but there were strident calls – even from Aisha, widow of Muhammad – for Ali to do nothing before bringing the killers of Uthman to justice. Supporting Aisha was Muawiya, the Umayyad governor of Syria, whose refusal to step down precipitated a war between his supporters and those of Ali. The caliph was unable to secure the critical victory he needed to bring Muawiya to heel – the Battle of Islam at Siffin is one of the more intriguing/historically critical – and was forced to acknowledge that he had lost control of Syria.

In the end, however, it wasn’t Muawiya that did in Ali; it was the Kharjites. This group, once Ali loyalists, had sprung up in opposition to their leader’s negotiations with the Umayyads, eventually declaring that the caliphate had ended with the death of Umar and that no one – not Ali, not Muawiya, not Amr bin al-Aas, the ruler of Egypt – was worthy of guiding the community – so they sent assassins after all three. Those assigned to kill al-Aas and Muawiya failed in their missions; the guy sent after Ali caught up with his quarry in a mosque in Kufa, Iraq, and with a poisoned sword, brought an end to the era of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Considering that Muhammad is the most common boy’s name on the planet, and the preponderance of contemporary Arab names that are derived from the people of this period, it’s interesting to look at some of the names by which one of the Rightly-Guide Caliphs was known:

Abu Bakr (‘The Owner of Camels’) was not his real name. He acquired this name later in life because of his great interest in raising camels. His real name was Abdul Ka’aba (‘Slave of Ka’aba’), which Muhammad (peace be on him) later changed to Abdullah (‘Slave of God’). The Prophet also gave him the title of ‘Siddiq’ – ‘The Testifier to the Truth.’

Muawiya established the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE), with his capital at Damascus, but like many dynasty-founders, he proved to be of stronger character that most of those who followed. Here’s a fairly forgiving evaluation of the Umayyad Dynasty from wsu.edu:

The Umayyads do not fare well in Islamic history which tells a tale of an unremitting line degenerate and weak caliphs; western historians have for the most part accepted this history. But the truth may be somewhat grayer. The Umayyads saw a great expansion of Islamic empire and were responsible for building a highly efficient and lasting governmental structure. The Umayyad caliphs could be startlingly brilliant both militarily and politically. And there is no question, that Islamic material and artistic culture has its roots in the Umayyad dynasty and the courts of Umayyad power.

This is not to say that the Umayyad caliphate was not unmarred by degeneracy and downright cruelty. But the Umayyads seem to be fairly uninterested in religious questions or the religious obligations of their position-it is rather as secular and secularizing rulers that their interest and greatness lies.

Cue the Line of Abbas

When they seized control of the Islamic Caliphate in 750 CE, the Abassids – a family descended from Muhammad’s paternal uncle, Abbas – quickly found that it behooved them to adopt many of the administrative and economic structures of the Umayyad Dynasty – structures which themselves were of Persian and had been incorporated into the caliphate since shortly after the Islamic conquest of Iran – they had usurped. The end of the Umayyads marked the end of the Arab-only club that Muslim leadership had become; prestige and power were now proportional to one’s proximity to the Caliph’s ear, not beholden to tribal and family relations. Abbasid rule, in a sense, leveled the playing field for non-Arab Muslims within the vast caliphate, and the powerful ethnic minority Persians were the prime motivators and beneficiaries of this liberalization. A great example of this was their army – much of the Abbasid force (in the early days, at least) was comprised of men from Khorasan (northeastern Iran) and were led by Abu Muslim, a Persian.

Under al-Mansur (754-775 CE), the capitol of the caliphate was moved from the ancient, dusty fortress of Damascus to the brand-spanking new cosmopolitan crossroads of Baghdad, only a few miles away from the ancient Parthian/Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon. The Persian Barmakid family was placed in charge of the administration of the caliphate, and by the reign of al-Mansur’s Sassanid-obsessed son al-Mahdi (775-785 CE), the caliph’s court had adopted the appearance and etiquette of pre-Islamic Persian royalty.

There is a solid argument to be made that the golden age of the Abbasids – generally agreed to have been during the reign of Harun al-Rashid (786-809 CE) and the early part of that of his son, al-Mamun (813-847 CE) – was largely due to a combination of distinctly non-Arab sources: Persian intellect and Chinese technology. Indeed, it was the panicked retreat of a Tang Dynasty army that allowed the thinkers of the Abbasid dynasty to write down all their philosophical grokkings.

wavy-line flashback sequence…doo doo doo doo do…doo doo doo doo do…

You’re at a place called Talas, in Kazakhstan. Imagine a windswept plateau, about as far from the ocean as any place on Earth, bisected by a cold mountain stream. Now populate the stark landscape with 150,000 Muslim troops, mostly cavalry, and about twice that many Tang Chinese, mostly infantry. The year is 751 CE, the stakes are religious and cultural dominance of Central Asia, and China loses, badly. Their camp is captured by the rampaging Abbasids, and among the treasures the Muslims loot is a device that – once its secrets are revealed by enslaved POWs, of course – will allow for the broad dissemination of knowledge that will occur during both the Abbasid golden age and the European Renaissance. The Muslims have captured a paper-maker.

…wavy-line return to normalcy…

Once it became possible to write something down without having to kill and skin an animal, culture-enhancers like universities and general literacy became feasible. Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, established around 800 CE – about the same time Charlemagne was being lionized in Europe for opening a handful of schools and working to standardize the Western European alphabet – was a repository for the most advanced of the world’s thinking. In fields as diverse as astronomy (and you were thinking the Chinese invented the astrolabe!), mathematics (“hey, man, what did you get on your al-jabr test?”), and architecture (it’s no coincidence that Spanish colonial buildings in the Americas have a distinctly Moorish look to them), thinkers from across the caliphate – propelled by an undercurrent of ethnically Persian influence – made huge advances.

Once it became possible to write something down without having to kill and skin an animal, culture-enhancers like universities and general literacy became feasible. Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, established around 800 CE – about the same time Charlemagne was being lionized in Europe for opening a handful of schools and working to standardize the Western European alphabet – was a repository for the most advanced of the world’s thinking. In fields as diverse as astronomy (and you were thinking the Chinese invented the astrolabe!), mathematics (“hey, man, what did you get on your al-jabr test?”), and architecture (it’s no coincidence that Spanish colonial buildings in the Americas have a distinctly Moorish look to them), thinkers from across the caliphate – propelled by an undercurrent of ethnically Persian influence – made huge advances.

A Jumble of Difficult-to-Spell Dynasties

The Persians were still Sunni at this point (don’t worry: we’re getting there!), with the majority of the Shi’a sect living in southern Iraq. Most of the conflicts between the Shiites and the Sunnis were occurring there, though later on I’ll mention a couple of important events in Shi’a history that do transpire in Iran.

The Shi’a distractions, along with the founding of rival dynasties – as in Spain, where the Umayyads tried to resurrect themselves, and Egypt, where the descendents of Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter, set up a Shiite shop – competed for influence with the caliphate and diverted attention away from the peripheral provinces in the east and north of Persia. They forgot that if there’s one thing the long history of the Persians has shown, it’s that the people of those particular regions will declare independence at the first sign of inattention or weakness on the part of their would-be overlords. Here’s a listing of the various empires and rebellious provinces that emerged as the Abbasids declined and eventually fell:

- Tahirid dynasty (821-873) – the first Persian Muslim dynasty arose in Khorasan, including parts of Iran, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan; capital at Nishapur. Founded when a leading Abbasid general took his winnings and declared independence.

- Saffarid dynasty (861-1003) – arose south of the Tahirids, annexed Khorasan after defeating the them in battle in 873 CE; capital at Zaranj (present-day Afghanistan). Conquered their way from northern India to the doorstep of Baghdad, but didn’t long survive the passing of their founder – they became a vassal state of the Samanids in 900.

- Samanid dynasty (875-999) – considered the founders of the Tajik nation and claiming descent from one of the Great Houses of Iran, they controlled much of Central Asia in their heyday; capitals at Bukhara, Samarkand, and Herat. Profoundly Sunni, the Samanids repressed Shi’a Islam (except for “Twelvers”), and left a cultural legacy of evangelism that had major impact on the conversion of the Turkic tribes – and thus, on all of western history.

- Ziyarid dynasty (928-1043) – centered in the area north of Teheran and south of the Caspian Sea; captured the cities of Hamadan and Isfahan. Promoted science through patronage of astronomer al-Biruni, built oddly-shaped tombs with the glass coffin of leader Qabus suspended in the middle of the tower.

- Buwayhid dynasty (934-1055) – powerful Shi’as based on the south shore of the Caspian, organized a confederation out of the crumbling Abbasid state; capital depends on which of the federated states one is talking about, but Fars, Jibal, and Iraq always exerted powerful influence. Royalty was known as “Grand Vizier” in Baghdad, but called themselves ” Shâhanshâh,” the ancient Persian term for “king of kings.”

- Ghaznavid Empire (963-1187) – a Persianized Turkic group (orginially part of the Slave-Guard of the Samanids) that came to rule Khorasan, Afghanistan, and Northern India. More about them in History for Kossacks: Medieval Afghanistan.

- Seljukid empire (1037-1187) – only the first in a string of Turkic-speaking groups descended from Central Asian nomads that became Persianized Sunnis before moving on to conquer everything from the gates of Byzantium to the Punjab. They reduced the caliphate to the size it was when the Crusaders arrived (that is to say, Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Syria).

Although the Shiite Buwayhid dynasty (which was ethnically Turkic enough to term its leader “sultan,” a title which stuck) gained great power over most of the eastern Abbasid empire – even setting up a 90-year dynasty in Iraq after their capture of Baghdad in 945 CE – and the Ghaznavids would give us the brilliance of Omar Khayyam, it was the Seljuks who really reshuffled the deck.

They came, these descendents of a Turkic-speaking guy named Seljuk, down from Central Asia in the 10th and 11th centuries. They settled in northern Iran, north of the Oxus River in Transoxiana, in cities they had quietly-but-permanently taken from the Sassanids centuries before. They slowly converted to Sunni Islam, but then, smelling blood in the Abbasid-dominated Euphrates, they moved in for the kill in the first half of the 11th century.

It’s All About the Outsourcing

It wasn’t only external pressures that doomed the Abbasids; they did plenty to screw themselves. The story goes back to the first Abbasid caliph, who had appealed to Shiites to support his claim to legitimacy on the basis of his being descended from Muhammad’s uncle. Conveniently forgetting that the followers of Ali had come through for him when it counted, the ever-pragmatic Abbasids made Sunnism the state religion of the caliphate, then bungled several opportunities to bury the scimitar with the Shi’a. Just to make sure they’d cut off all of their noses to spite their own faces, al-Rashid turned on the loyal, empire-administering Barmakid family, disgraced them, and removed them from power.

But it was the outsourcing that truly did them in. As early as the 9th century, the Abbasids were bringing a private slave army of Turks – called Mamluks – to Baghdad, and to their later capitol at Samara (200 km north of Baghdad, on the east bank of the Tigris). And while the Mamluks did indeed serve as an effective stabilizing force against the Byzantines and the various Shi’a and Persian uprisings, history has also shown us that an over-reliance on mercenaries, foreigners, and slaves in an army can be as dangerous to the country which raises that army as to the enemy against whom it is raised. It was no exception for the Abbasids; by 940 CE, de facto control of the caliphate had been passed to the Mamluks, who went on to invade and conquer Egypt. They remained influential well into the Ottoman and Napoleonic periods, hundreds of years later.

And of course, sometimes when you’re running an empire you find yourself in need of a group of discreet, violent badasses to do your dirty work for you. For the sultans, that group was a gang of thugs called the Ismailis, who operated out of a castle at Alamot, between Rasht and Teheran. They smoked hashish and killed people for money, working for Crusader and Muslim alike, for more than 150 years, and the odd intersection of their profession and their vice has resulted in an even odder bastardization of language: from “hashishiyya” (“people of the hash”) is derived our word “assassin.” And from a strategic perspective, it just can’t be a good idea to have a nest of those guys occupying high ground in the middle of your kingdom…

The Abbasids thought they had a deal with the Seljuks when they agreed to give one of the Seljuk warlords the right to call himself “King of the East and the West,” but this particular Turkic group, operating out of their capitol at Isfahan (and later Merv), eventually bit the hand that fed it, too. The Seljuks decided to carve off their share of the dying Abbasid empire before the Byzantines, Mamluks, and the heretical (in their eyes, at least) Fatamid Dynasty in Egypt claimed all the best parts for themselves. By 1055 CE, the Seljuks were in control of Baghdad.

Perish the Turkic Raiders

Under the leadership of the Seljuk kings Alp Arslan (1059-1072 CE) and his son, Malik Shah (1072-1092), Iranian dominance once again spread from China to Byzantium. Their two Persian viziers Nizam al-Mulk and Taj ul-Mulk handled the administration and the politics, leaving the Turks free to kick the Byzantines around on the field of battle. This happened decisively at a place called Manzikert, north of Lake Van in modern Turkey, in 1071 CE (or five years after the Normans took England). Manzikert is such a decisive battle, and with such a cool, treacherous back-story, that I’m going to exercise historian’s prerogative and table the details for a future diary.

Malik Shah died in 1092 CE, and an all-too familiar struggle for secession ensued. The Seljuks thus found themselves in disarray a few years later, when an armies of Crusaders began emerging from Byzantine lands and burning their way across Seljuk territory on their way to Jerusalem. Though many of these first Crusaders were mobs of unarmed peasants who were slaughtered to a man, the Christian attacks weakened the regional Seljuk warlords, and in the end, sealed the fate of those who ruled in Turkey and northern Iraq. Despite the Kurds producing such great leaders as Nur al-Din and Saladin – who were forced by circumstances to focus their attentions westward – the Crusades, internal conflicts, and the ole’ rebellious-provinces thing all served to disrupt Seljuk efforts to reconsolidate, and by the second half of the 12th century CE, all that remained of the Seljuk empire was the Sultanate of Rum, a precarious kingdom carved out of formerly Byzantine holdings in Anatolia.

An army of horsemen this way comes

By 1153 CE, the Princes of Kwarezm, rulers of Khorassan, had struggled their way to domination of Iran from the eastern slopes of the Zagros to the borders of China and Afghanistan. They proved to have had too little time to consolidate their defenses, however, before an outrageously destructive army of horsemen, unforeseen and completely unbidden, stormed across their eastern frontier in 1219 CE.

The Mongols took Transoxiana with the capture and sack of Samarkand (one of the oldest currently-inhabited cities on Earth, by the way) in 1220 CE, and extended their reach as far as Azerbaijan by 1221 CE. The remainder of Persia was conquered by Genghis Khan’s grandson, Hugalu, who subdued the fractured kingdoms – already under strain from the refugee problems that always preceded the Mongols – on his way to Baghdad. There, Hugalu ground the remains of the Abbasid caliphate beneath the heel of his riding boot: 800,000 Muslim inhabitants of Baghdad – Arab and Persian alike – were slaughtered, vast areas of the city were ravaged, and irreparable damage was done to the canals and irrigation systems. Halted by later engagements with the Egyptian Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut, the Mongols settled down to administer – and brutally wring every last drachma of treasure from – the entirety of Persia and Mesopotamia, not to mention China, Korea, and Russia.

The Mongols took Transoxiana with the capture and sack of Samarkand (one of the oldest currently-inhabited cities on Earth, by the way) in 1220 CE, and extended their reach as far as Azerbaijan by 1221 CE. The remainder of Persia was conquered by Genghis Khan’s grandson, Hugalu, who subdued the fractured kingdoms – already under strain from the refugee problems that always preceded the Mongols – on his way to Baghdad. There, Hugalu ground the remains of the Abbasid caliphate beneath the heel of his riding boot: 800,000 Muslim inhabitants of Baghdad – Arab and Persian alike – were slaughtered, vast areas of the city were ravaged, and irreparable damage was done to the canals and irrigation systems. Halted by later engagements with the Egyptian Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut, the Mongols settled down to administer – and brutally wring every last drachma of treasure from – the entirety of Persia and Mesopotamia, not to mention China, Korea, and Russia.

Tamerlane: A Guy Would Could Scare Even Dick Cheney

Hulagu became an Ilk-khan (“subordinate khan”) upon the succession of his brother Kublai to their father’s throne. The Ilkhans ruled Persia for the next 80 years, and though the first few encouraged Tibetan Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity, by 1300 CE or so, the Ilkhan Ghazan converted to Islam and state religion once again became the order of the day. Those who had been earlier encouraged were now persecuted; the resurgence of fire-and-swordpoint Islam – and the at-least-partly-ethnic backlash against it – was so powerful that with the death of the 9th Ilkhan, Abu Said, in 1335, the ilkhanate fell into disunion and quickly disintegrated.

One of the small kingdoms that emerged in this period gave rise to one of the most feared names in all of the Middle East’s bloody history: Timur the Lame, or Tamerlane. He was neither Sunni nor Shi’a, but of a Sunni form of Sufism (there aren’t many of those) called Naqshbandiyyah, but in the end, he didn’t really give a rat’s rosy red ass about the religion – or even the administration – of the lands and peoples he conquered. His exploits are many, his deeds severe:

- he once marched an army of 100,000 men deep into Russia – he captured Moscow – in a front ten miles wide in order to trap and destroy the Golden Horde

- he brought under his control lands as far west as the Hellespont and Smyrna (modern Izmir, Turkey), east to the Ganges, and north to the borders of Mongolia

- his Transoxianan capitol of Samarkand (in modern Uzbekistan) became the most influential and architecturally beautiful city in Central Asia

- the jury’s still out on whether he permitted his troops to plunder and rape the city of Delhi or simply lost control of his rampaging horde. Either way, the city was plundered and raped.

- when he captured Baghdad in 1401 CE, he slaughtered 20,000 inhabitants by issuing a command for each of his soldiers to return with two severed heads.

- his name is still used in some parts of central Asia as a boogeyman to frighten disobedient children into behaving – and he died 600 years ago.

Such empires usually do not long survive the megalomaniacs who build them, and the empire of Tamerlane was no exception. Though it existed in some form or another until 1506 CE, the power of the Timurids declined rapidly after the death of their founder in 1405 CE, just as he was about to march against Ming China.

One last weirdness about Tamerlane: It is said that a curse was carved upon the entrance to his tomb, warning that whoever disturbed the final resting place of the mighty conqueror would have war visited upon his country. Makes one hope that the exhumation of Timur’s remains by a Russian scientist on June 19, 1941, didn’t have anything to do with the fact that Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, three days later.

Sufi Safavids Seek Shi’a Society

While the Timurids and the remnants of the Mongol Empire eroded away, feelings of violent self-determination were once again arising in Persia. “Black Sheep” and “White Sheep” Turkoman dynasties struggled for control of Tabriz (the White Sheep won), seemingly unaware of the growing strength of a powerful force to their north and west, in Azerbaijan: the Safavids, who were descended from a founder of one of the Shiite branches of Sufism.

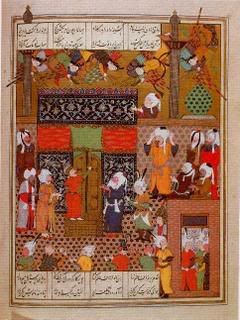

The Safavids were a Persian family, but after the conversion of Junayd, the head of the Safavid Sufi order in 1477 CE, to militant Shi’aism, much of their support came from Turkomans, Syrians, Anatolians, Armenians, and the Shiite tribes of Upper Mesopotamia. Under the leadership of Shah Ismail I (r. 1501-1524 CE), the Safavids imposed their brand of Shi’a Islam from Baghdad to Herat. They were aided in this by the support of their military elite, whose elaborate red headdress earned them the nickname “Redheads.”

The Safavids were a Persian family, but after the conversion of Junayd, the head of the Safavid Sufi order in 1477 CE, to militant Shi’aism, much of their support came from Turkomans, Syrians, Anatolians, Armenians, and the Shiite tribes of Upper Mesopotamia. Under the leadership of Shah Ismail I (r. 1501-1524 CE), the Safavids imposed their brand of Shi’a Islam from Baghdad to Herat. They were aided in this by the support of their military elite, whose elaborate red headdress earned them the nickname “Redheads.”

I won’t try to draw the distinctions that evolved between Shi’a and Sunni Islam in this diary; let’s save that enormous can of worms for another time. For now, I’ll just quote the Library of Congress on the subject vis-à-vis the Safavids:

The distinctive dogma and institution of Shia Islam is the Imamate, which includes the idea that the successor of Muhammad be more than merely a political leader (as opposed to the Sunni idea of the Caliph). The Imam must also be a spiritual leader, which means that he must have the ability to interpret the inner mysteries of the Quran and the shariat. The Twelver Shias further believe that the Twelve Imams who succeeded the Prophet were sinless, free from error, and had been chosen by God through Muhammad.

The Imamate began with Ali, who is also accepted by Sunni Muslims as the fourth of the “rightly guided caliphs” to succeed the Prophet. Shias revere Ali as the First Imam, and his descendants, beginning with his sons Hasan and Hussein (also seen as Hosein), continue the line of the Imams until the Twelfth, who is believed to have ascended into a supernatural state to return to earth on judgment day. Shias point to the close lifetime association of Muhammad with Ali. When Ali was six years old, he was invited by the Prophet to live with him, and Shias believe Ali was the first person to make the declaration of faith in Islam.

…snip…

In Sunni Islam an imam is the leader of congregational prayer. Among the Shias of Iran the term imam traditionally has been used only for Ali and his eleven descendants. None of the Twelve Imams, with the exception of Ali, ever ruled an Islamic government. During their lifetimes, their followers hoped that they would assume the rulership of the Islamic community, a rule that was believed to have been wrongfully usurped.

The story of the 8th Imam, Reza, is associated with Iran and is part of the larger tale of Safavid Shiaism, though the story itself comes from the time of al-Mamun and the early Abbasid Caliphate. Al-Mamun invited Reza to travel up from Medina to the court at Merv, and Reza’s sister Fatima began making her way to Arabia, so as to accompany Reza on his journey. She took ill while en route, and died at Qom, Iran, which later became an important theological center built around her shrine. As for the 8th Imam,

Mamun took Reza on his military campaign to retake Baghdad from political rivals. On this trip Reza died unexpectedly in Khorasan. Reza was the only Imam to reside or die in what is now Iran. A major shrine, and eventually the city of Mashhad, grew up around his tomb, which has become the most important pilgrimage center in Iran. Several important theological schools are located in Mashhad, associated with the shrine of the Eighth Imam.

Reza’s sudden death was a shock to his followers, many of whom believed that Mamun, out of jealousy for Reza’s increasing popularity, had him poisoned. Mamun’s suspected treachery against Reza and his family tended to reinforce a feeling already prevalent among his followers that the Sunni rulers were untrustworthy.

ibid.

I guess the point of all this is: Shiites and Sunnis have deep-seated, and perhaps irreconcilable, differences between them. Within the context of greater Islam, they are as different as the Catholics and Protestants of Northern Ireland, and like the differences between those two groups, the depth of historical animosity is difficult for outsiders (like, admittedly, me) to grasp. When Ismail I declared himself Shah and raised Shi’a theology to a power it had not held since the demise of the Fatamids, he was choosing for Iran a course that would ensure sometimes-violent disagreement with Sunni neighbors for centuries to come.

Next time in the Cave of the Moonbat: The Safavids launch yet another Persian Golden Age – man, these people sure have a lot of those things…

Historiorant:

Not enough time for a nice, leisurely rant this time around, so I guess I’ll leave off on my sabbatical with only the following challenge: how would you describe the American Empire, if you only gave yourself a five-line bullet point in which to do it?

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

But then again, the wonderful thing about history is that it’s always there, waiting for you…

The American Empire:

1. emerged in the consumerist phase of global capitalism (1948-1971) and became bloated in its Iraq invasion period (2003- ) before collapsing some time in the 21st century CE

2. was based on control of the world’s reserve currency, the US Dollar

3. was fancied as a disciplinary mechanism by the transnational capitalist class, which extracted the world’s wealth through IMF/ World Bank structural adjustment programs, enforcement of WTO regulations, and currency manipulations

4. met its final end with the drying-up of the world’s high-quality crude oil reserves, which, when burned at the rate of 85 million bbls./day, created a ravaging abrupt climate change effect by adding huge quantities of CO2 to Earth’s atmosphere

5. achieved its most dreadful manifestations in the reign of its most sadistic Emperor, George Bush II, who caused a currency collapse by his frivolous military spending…

Beautifully done. Thank you.

I am saving this one off the hard drive so I never lose it.

Of course I am not nearly as schooled as you in this part of our world’s history and my take my be incredibly simplistic but I see in Persia/Iran’s history the essential struggle for man to better him/herself and to achieve his/her dreams for themselves and family.

First came Cyrus the Great – a completely Secular man who united Persia for the first time (550bc) into a sprawling nation under a bill of rights that is actually referred to by Jefferson as his inspiration for our Bill of Rights. When Cyrus was killed in battle, the bill was with him sealed in a case. It now hangs in the lobby of the UN where it has been translated into every language of every nation belonging to the UN.And what were Cyrus’ key beliefs: he abolished every form of slavery and declared all men equal. he believed in religious freedom and the right for all men and women to co-exist peacefully and in prosperity.

And yes the mighty dynasties that followed – many were warriors. Unfortunately, as you point out, but that I would like to underscore – they also brought with them the concept of ‘the court’ or class of power and privlidges not allowed by to any commoner – dashing the essential promise of Cyrus.

There are some historians that believe that the success of Mohammad and quick spread of the Muslim religion lay in its essential promise that is one lives a devout life one has as good a chance as any other in the afterlife – returning Persia/Iran back towards a time that all men were created equal. That makes sense to me.

The Golden Age of Islam