Theodicy, or the problem of evil, can be stated in its classical form as a trilemma — a three-step dilemma.

(1) God is all-powerful.

(2) God is all-good.

(3) Evil exists in the world.

The combination of (1), (2), and (3) is internally contradictory. Logic demands that at least one of them be declared false. Yet, for most of the history of Western thought, all of (1), (2) and (3) were regarded as plainly true. Thus were philosophers and theologians – and pretty much anyone else who thought about it – exercised.

Nowadays, at least in some circles, there is no problem of evil, so formulated. “Enlightened” people may still wonder about the problem of evil in a watered-down form. They may ask, “Why is there evil in the world?” That is, they may wonder why (3) is true. To do so is still to engage, to wrestle with, theodicy, in some sense.

But since most people in the West nowadays have no inner qualms about denying (1) and/or (2), the trilemma is dissipated. The logical urgency, and the metaphysical crisis, generated by the conjunction of (1), (2), and (3) is gone.

I say that most people have no qualms about denying (1) and/or (2). One way to deny them both, obviously, is to deny that God exists at all. That takes care of both (1) and (2) in short order. But most people, going by polls, do not deny that God exists. Rather, I take it, most people have a more easy-going attitude to God than did their ancestors. “Is (1) really true?” Meh, who knows. “Is (2) really true?” Perhaps that one still raises some butterflies.

If we accept that God is all-good and deny that God is all-powerful – that is, if we work our way out of the trilemma by accepting (2) and (3) and denying (1) – we seem to left with a world in which there are spots of Godly absence; places where God isn’t, or where Her/His influence isn’t. Voids of divinity that pockmark the universe like holes in a Swiss Cheese.

From this standpoint it makes sense to say, or anyway it seems to make sense to say, that evil is an absence or lack. “Evil” names not something that one is but rather something that one isn’t. And indeed, it is sometimes said that Hitler was explicable by what he lacked; that the Khmer Rouge requires a negative, not a positive, avowal, to bring it within the fold of comprehensibility.

On the other hand, if we deny (3), we are either Pangloss from Voltaire’s Candide, or else we are “typical liberals.” Pangloss ran around Europe insisting all was for the best, even as he lost now an arm, now a leg, to the mindless idiocy of various wars and calamities. Pangloss, by the way, was Voltaire’s (1694 – 1778) way of making fun of Leibnitz (1646 – 1716), a philosopher who insisted that we lived in the best of all possible worlds. Well, that’s one way out of the trilemma.

We can also, if we are “typical liberals,” deny (3) by saying that all apparently evil acts are explicable by psychological malfunctions. We can appeal to Hitler’s childhood, or the effects of Pol Pot’s environment. Note that, if we do this, we are replacing, or trying to replace, a metaphysical question with an empirical question. It might be that we are changing the subject. Explaining why Ted Bundy committed evil acts isn’t, all by itself, to prove that the acts were not in fact evil. To think that is to carry in a lot of philosophical baggage unannounced and probably unnoticed as we dump it on the floor.

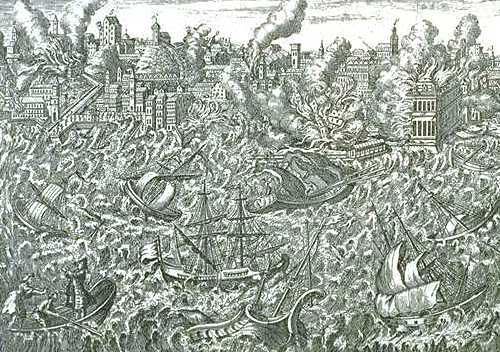

What sorts of things we count as evil, as instances or examples of (3), also depends on our metaphysical world-view. For a very long time, the 1755 earthquake at Lisbon was regarded as the apotheosis of evil in the modern world. Kant, Voltaire, Goethe, Rousseau struggled with its meaning.

(Indeed, one of the best recent books on the history of philosophy contends that we have been misinterpreting the history of modern philosophy. All those thinkers were struggling not so much with the staid and polite Problem of Knowledge, as we in America and England are typically taught, but with the terrifying and decidedly impolite Problem of Evil. To miss this, the author, Susan Neiman, convincingly contends, is to dismiss the motivation, the vexing and immediately felt ignorance in matters of mortal importance that brings us to philosophy in the first place.)

Nowadays, of course, Auschwitz is our apotheosis of evil. It is The Example by which we in the West remind ourselves that evil exists. It is what we struggle to understand. By contrast, we tend to regard anyone who views a mere earthquake as “evil” as merely quaint. We think this way because our world is less enchanted than it was, even a quick 200 years ago, and because evil has moved – by turns of culture too deep to explain in a blog post, even if I had the explanation – inward. It’s in our heads, in our intentions and thoughts, not in the world. Evil, we think, is in here, not out there.

I‘ve been musing on theodicy tonight because I notice that the New York Review of Books has an article about it. And here I have to take direct quarrel with the author, Tony Judt. Whatever we choose to do with theodicy, however we wrestle with it, however deeply or shallowly we feel the stress of the old trilemma or the new inward turn, we must not, must not, must not, write paragraphs like this:

My fourth concern bears on the risk we run when we invest all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem, however serious. The costs of this sort of tunnel vision are on tragic display today in Washington’s obsession with the evils of terrorism, its “Global War on Terror.” The question is not whether terrorism exists: of course it exists. Nor is it a question of whether terrorism and terrorists should be fought: of course they should be fought. The question is what other evils we shall neglect-or create-by focusing exclusively upon a single enemy and using it to justify a hundred lesser crimes of our own.

Our crimes, we understand, are “lesser.” By what standard we make this determination, I do not know. Not by body count, certainly. Not by the relative rationality of our bombings and torture chambers. And not because “they started it.” Even if that were true, and no less true claim has ever been made in the history of geo-politics, even if that were true it would have nothing to do with the problem of evil, or our participation in keeping it alive.

More to the point, the uses of “evil” in Bushy rhetoric (“evil-doers,” “axis of evil,” “forces of evil”) and in Washington rhetoric generally are not examples of “tunnel vision” at all. To think this is to think that the political (in the pejorative sense) rhetoric of evil is meant, in the first place, to refer to evil, and that the politicians who use it have missed something. But they have not. When Bush or Cheney or Reid or Schumer or Clinton or Obama speak of the “evil” we confront they are committing an evasion, a manipulation, and therefore an affront not just to metaphysics but to human decency. And they are doing it on purpose.

To think that we are “invest[ing] all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem, however serious” and that that problem is either “terrorism” or “evil” is not just to point out the problems inherent to the easy political use of the word “evil” but to participate in it. I have to assume that Judt is smarter than this; that he is writing for what he perceives to be an audience that can take looking in the mirror only in small doses. I doubt that his audience is really that squeamish (perhaps I’m an optimist). But the pretend idea that we can’t look in the mirror more rigorously is often the fake justification for a quiescent press. I’d rather not see an essay on theodicy, of all things, engage in it.

If there is one thing that I think we can say we have learned since World War II, or anyway since 2001, it is that Hannah Arendt’s memorable phrase “the banality of evil” is at best an incomplete description of the enormity we confront when we confront the problem of evil close to home. Arendt was referring to the calm lack of introspection or care on the part of the Nazis. Evil, when it comes, she was suggesting, does not come snarling and obvious. It comes with a lack of libido, in a suit, with a pen and a pile of forms.

Without comparing the Nazis to current America – to do that would be to miss the point I am trying to make entirely – I think we can say that we’ve learned that evil is not always without libido. Cheney and Bush, whatever else they are doing, are positively evincing joy at the wanton destruction of countries and constitutions and what Jefferson, following Locke, regarded as the natural rights of humans. Their followers are no less strident. There is no banality here. There is no absence of drive. There is lust and affirmation. In the non-pejorative sense of “political” there is political lust. Political affirmation. Of evil.

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas wrote:

[P]erhaps the most revolutionary fact of twentieth-century consciousness . . . is the destruction of all balance between explicit and implicit theodicy of Western thought.

Quoting this passage from Levinas , Neiman wrote:

An almost obsessive, sometimes questionable interest in cataloging twentieth-century horrors continues to fill the world with testimony in all forms modern media has as its disposal. But most agree that we lack the conceptual resources to do more than bear witness. Contemporary evil has left us helpless.

Speaking of Auschwitz, as Neiman was, she may be correct. But in other areas the problem is not lack of resources but lack of courage. If we let either Nazism or political expediency render us literally unable to articulate thoughts about evil, to render all of our theodicy implicit, to make it impossible to see evil in our own lands, and to conceptualize it and speak its name, then we will not have advanced, not have learned, not have earned anything.

If the word “evil” is good for anything at all, then it must be good for naming what we see before us when we see it before us. If theodicy is good for anything at all, it must be for helping us to understand why it is there, and how to conceptualize it and fit it into our understanding of our world and ourselves, lest it remain, unspoken but not uncommitted, in our own disenchanted future.

81 comments

Skip to comment form

I pick that one!

Seriously, I think the questions raised in your essay are good ones … our society and culture’s definition of evil has gotten awfully twisted, imo.

resides in conflicts of interest, particularly “The American Way of Life,” which as we all know is not negotiable, but which, as we all know, is crumbling in the face of carrying capacity, which leads to evil, libidinous evil.

in a fundamentalist protestant home, the conflict you describe between 1,2, and 3 gnawed away at me. I could never have articulated it as clearly as you have, but it was one of the root questions that just hung on and wouldn’t let go.

Once I abandoned my belief in god, I went where you describe liberals going – to the empirical understanding of root causes of evil within human beings. It has seemed pretty clear to me that both good and evil are potentialities that are available to be nurtured in any human being.

I might have further to go on thinking this through and I thank you for the challenge.

if god is concieved of as the highest power……

and evil exists….

then god must be non good….

and non is not not……….

perhaps good and evil is not the concern of god……

perhaps these are the concerns of us, humans….

Dick Cheney?

and perfectly appropriate for where we are.

what if this is just how things happen? and we have choices.

what if we don’t have to do double back flips? what if we just say: i choose against ethnic killing and then do something to push back and STOP it.

look at the absolute savagery of some American Indian tribes to their neighbors. I think one good example is the christian-like (in a good sense) life of the Iroquois. but they were brutal to competitors.

now scale that up from small war parties or even hundreds of people fighting… to millions of people in our way. it was sartre who said “other people are hell”

the way we worked in tribal conventions has become perverted in this new scale.

and there are those of us who get the mismatch. but miss one small thing::: that we still adhere to an institutional explanation (evil) rather than relying on understanding nature and survival. we are evolutionary models that believe in consensus and resource sharing in order to survive (sustainability). and the fight, for us is against the George Bush models::: might is right, entitlement, and use of humans merely as another type of resource.

anyway. i use the word evil. but the more i think on it, the less i believe it exists as some devil or plot.

…and in the best of all possible worlds, evil is given us by god, so as to test the will of fallen man :}

Just a lovely essay. You jumped hard in a series of interesting directions regarding the problem of evil, I’m sure we agree on generalities, and I’m not inclined to poke at particulars :}

I guess what this trips for me is how a secular humanist raised eyebrow — at the idea of real evil — corresponds with actually being less evil. I really believe this: fanatics are assholes. That taking many things with a dash of salt makes us saner beasts…but that same impulse, when it ignores really nasty stuff, assumes that is just life, lets evil go by, abets it.

Pardon my not supplying references, but many religions have wrestled with the supposed contradiction you present. The general view, as I understand it, is that the presence of evil in the world is somehow useful. (Note: I’m going to use the word “God” in what follows to describe an creator of the universe and humanity who had some purpose in mind, although I cannot defend God’s existence as more than a hunch.) God has made it pretty much inevitable — scarcity of resources, tragedy of the commons, and all that — and this may be because God had no choice (as, perhaps, with 2 + 2 equaling 4 in base 5 and above) or because God wants it to work this way.

I think of the presence of evil as a problem with which God wants individual humans to grapple, perhaps, in some ways, to sharpen the luster of our souls. The nihilistic (and also, in my opinion, Randian) solution of redefining “evil” as “good” is pretty clearly not the right answer; nor, in my opinion, is the spiritual monist position (a la Bishop Berkeley) of pretending that the evil we see around us does not actually exist. Evil is evil: we are supposed to be repulsed by it and we are supposed to take it seriously rather than pretend it away. (God has given us plenty of reason both to take evil seriously and to wish we could pretend it away, but I don’t think that we’re put on Earth to cut through this Gordian not rather than struggle to untie it.)

Somehow, for a reason we don’t and perhaps cannot know, the universe works better when we must struggle with the existence of evil, so a good and all-powerful God — who could after all have chosen a universe that contains as little evil as a vacuum — allows it to exist.

That’s my religious belief, anyway; your cosmology may very.

which was to state that we’re thinking about (3) wrongly: evil doesn’t exist in the way that other phenomena do, but it’s a description of a human being’s turning away from God. In that sense the issue of whether God had created it or not becomes moot: the more pressing issue is whether God created free will. If so (and it is within the realm of pure good to create choice, if we think about choice as a reflection of freedom), then the act of not choosing God’s way is evil, but it’s not something that “exists” in any real sense of the word.

I certainly depart with Augustine on (1) and (2), but I appreciate that he helped change the discussion to focus on human agency rather than some abstract demon. His version is still crude (the problem of “evil” is much, much more complicated than bad choicemaking), but it was a step in the right direction.

Great essay, LC!

Did God come first? Or did the concept of The Chosen People come first?

I think it’s the latter.

I think what we have here is a rather sick need to explain how a particular group of people must be the best in the world, in the face of the cold facts that they keep having the crap beat out of them by their inferiors.

A theme that tragically has resonated farther beyond their shores than their grandest storytellers ever imagined.

God isn’t dead. He’s nuts.

thus giving us an anti-theodicy? Here’s what it would look like —

(1) Satan is really in charge here; “God” is Satan’s PR image.

(2) Satan is all-evil.

(3) A real, authentic spirit of God exists in the world.

After all, only Satan would ask human beings to “be fruitful and multiply” to the point where human action has created a massive extinction, the “sixth extinction” in Leakey and Lewin’s terms, and the only question left is one of how big it’s going to be. And only Satan would have created neoliberal globalization, the most recent, most innovative, and most powerful of the many forces which together, right here and now, destroy planetary ecosystem resilience on all levels.

So that explains my (1) and (2). The real mystery, then, is (3).

Good and evil, dark and light seem to be concepts outside ourselves they exist without humans. Or do they? Are we just observing the nature of things or have we out of self serving hubris and lack of perspective created these. In the west we have fragmented phenomenons and old texts to explain the universe, religions seem like human political hierarchy’s. Our ‘God’ is a human, who creates in our version of time and space, and we were created in his likeness, assbackward perhaps.

As a humanist I see good and evil as existing our little piece of the total. Karma, cause and effect, and balance are our theater of operation. As a spiritual being I somehow feel that if I lend myself to the dark, I affect the whole. My brother tried to get a draft deferment, for his ‘religion’ which he called middle gray. He is a painter and if you mix all the colors in equal amount you end up with middle gray a perfect blend. He felt that if he went to an evil war he was not only doing wrong on a personal human to human level but affecting the total energy and composition.

However call it what you will I deep down I know human evil when I come upon it. It’s in all of us. God is another matter which I cannot see due to my human perspective. A sweet and endless mystery.

Just as every cop is a criminal

And all the sinners saints

As heads is tails

Just call me Lucifer

‘Cause I’m in need of some restraint

So if you meet me

Have some courtesy

Have some sympathy, and some taste

Use all your well-learned politesse

Or I’ll lay your soul to waste

Pleased to meet you

Hope you guessed my name

But what’s puzzling you

Is the nature of my game

Attempts to answer that question have inspired religions and economic models that place the blame on the ones who suffer, or on a malevolent supernatural force.

To me, “evil” is the exploitation or apathy toward suffering; and “good” is any effort to understand and alleviate the causes of suffering. And, “God” is an excuse for both.

so I can’t take a position as I see the trilemma as a mental trap.

The problem is that it assumes an underlying agreed upon definition of god, which I do not hold. After 24 years of studying and spiritual practice and much contemplation on the the topic of ‘god’, I have come to reject the current common definition of god that comes out of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) and I have come to reject montheism on many levels. Monotheism is a highly problematic “doctrine” and I wish more people were willing to challenge it’s assumptions. However it’s pretty heavily embedded in the currenty western collective unconscious, so I’m not optimistic.

I view both modern religion and science as infected by monotheist assumptions. Their other big problem is the infection of literalism in religion. Sorry but you can’t point to or talk about god(s)like you can a table or a human being. God(s), if such exist, must be in some other realm that’s not physical and that’s very contentious right now. Then look at the push to find the one point of beginning of things in cosmology for instance. Only a few cosmologist dare to challenge the current mindset that there was a One Thing That Happened be the “beginning” of the universe. Only a few lesser voices talk about a cyclical universe that doesn’t really begin or end, that are attempting to reframe the discussion.

Let me say that for many years on my spiritual path I considered myself an inclusive monotheist (all gods are really different faces of The One). But there came a point in my understanding of the nature of reality where I could no longer sustain that belief. And when I finally let go of my belief in monotheism it was quite a revelation.

Ya know, you can believe in one god within the context of polytheism and you can have moments of oneness withing the context of polytheism but the pluralism inherent in polytheism is a much better fit for todays world and politics.

Now I’m a snarky polytheist troublemaker whose doing her best to stimulate thought on the “one and many problem”.

We don’t think of evil plants, or evil animals, or even evil snails (! see above), but humans can (we say) be evil.

Rousseau held simply that human nature is not evil, but good, or we might say, is itself. Only when human beings joined in a society where the product of human labor was alienated, seized, and appropriated by others, i.e., as private property, did the social being, homo sapiens, find his or her nature warped, thwarted, and changed.

Marx certainly took much of this from Rousseau and the other utopian socialists, though he felt he made it scientific, because materialistic.

The various theodicies all rely on teleological assumptions. But as Darwin showed, teleology is not tenable. Our minds (including my own) are too inured to current morality to be able to see the terrible afflictions of our fellow humans as anything but evil and wrong, and not the inevitable reshuffling of natural selection trying to make organisms adapt (which puts it in a teleological way, but here the teleology isn’t morality or god but differential reproductive success).

When I go looking for a theodicy to comfort me, I go to Milton, as only he really knew how to “justify the ways of God to Man.” (And that’s because, as Blake put it, he was of Satan’s party, but didn’t really know it.) Milton shows that the stuggle of humanity transcends both God and Satan, that in the blind struggle to exist, the quest for knowledge slowly moves us forward.