According to the latest wire reports, the verdict is in: even (and perhaps especially) he who would be the next Bush doesn’t know crap about Iran. This is unfortunate; one would think the disastrous invasion of Mesopotamia would’ve reminded us that we’re talking about a region of the world that breaks empires as a matter of course.

Tonight’s historiorant seeks to address just one of the lessons that needn’t have cost us 4000+ of our own soldiers’ lives to learn: that failing to accurately assess an enemy’s capabilities frequently plays a major role in victories and defeats in Southwest Asia. Marcus Licinius Crassus didn’t appreciate that fact, nor did Hulagu Khan centuries later. Join in the Cave of the Moonbat, and we’ll see if we can’t help to educate our misguided Republican brethren before they foist yet another hotheaded dumbass upon the American citizenry – and hopefully forestall our getting enmeshed in yet another Carrhae, Ain Jalut, or Chaldiran.

Historiorant: A few weeks ago, the sagely klizard, while guest-hosting here in the Cave, laid down the definitive historiorant on Sufism and its impact on Iran – if you haven’t read it, you really ought to; I’ll wait ’til you get back…

…Good. As you saw, klizard’s article picked up the History for Kossacks: Persia series where I’d left off for my month-long hiatus – the confusing, multi-kingdom period of Iranian history between the arrival of the Umayyad Caliphate in the late 7th century to the rise of Shiaism during the early Safavid period (about 8 centuries later). Tonight, I’ll pick up the story again, more or less where klizard left off: at the Battle of Chaldiran.

The tale thus far: At the conclusion of the last rather ill-attended (tsk, tsk) historiorant on Medieval Persia (sorry for the delay in getting this one posted, btw; last weekend my ‘net connection was savaged by storms), posted back at the end of February, the Safavids were on the verge of achieving dominance over turn-of-the-16th-century Iran, and the empires surrounding them were none too pleased about it. A few decades before, the grandfather of Ismail I, Junayd, had transformed a quiet sect of Sufism into a revolutionary Shiite movement, and now, in 1501, the 15-year old Shah Ismail I-to-be stood poised to reap the rewards.

Ottomans Were Not Always Furniture

or

Never Bring a Horse Archer to a Gunfight

The Ottoman Turks, who had breached the walls of Constantinople (and in so doing, closed the final chapter in the saga of the Roman and Byzantine Empires) in 1453, harbored imperial aspirations. With the zeal of the freshly successful, they were inadvertently driving allies into the Safavid camp by persecuting anyone in their territory found guilty of non-Sunnism. This included some of their own soldiers.

From his base in Azerbaijan, Ismail recruited a group of these disaffected Shiite Turkish militiamen – nicknamed Qizilbash, or “Redheads,” for their elaborate headdresses – from as far away as Anatolia. When he had gained enough support, he struck at the Aq-Qoyunlu confederation, a coalition of lords that oversaw Armernia, Azerbaijan, and Northwest Persia from the mid-14th century until their final demise in 1508. In 1501, Ismail defeated them at the Battle of Nakhichevan and captured the city of Tabriz, which subsequently declared the capital of the new Safavid Empire.

Ismail followed the now-ancient Persian tradition of claiming rulership through ancestral bloodlines. To prove their Shi’a cred, the Safavids held themselves descended from Muhammad’s daughter through the Seventh Imam, Musa al-Kazim. To prove that proud Persian fighting blood ran through his veins, Ismail later claimed descent from the line of Sassanid rulers, as well – and since they claimed to be descended from the mighty Cyrus and his Achaemenians…

Map via uccalgary.ca

Ismail expanded his Shi’a state relentlessly for the next decade, eventually bringing to heel regions as far off as Van, Karbala, and Najaf in the west, and Herat and Khorasan in the east. In doing so, however, he made himself some enemies: the Uzbeks, Sunnis who were driven from the newly-Safavid lands in the northeast, for example, were pretty pissed about having been chased across the Oxus. From their newly-captured capital at Samarkand, the Uzbek Shaibanid dynasty would continue to harass the Safavids for a long time to come. Even more ominously, the Portuguese in 1507 grabbed a little piece of Persia for themselves, when they took and occupied the island of Hormuz from the fleetless Safavids. They later went on to establish a presence at Bahrain.

Those pesky Ottomans kept coming back for more, too, and since they were pretty much the Southwestern Asia superpower of their day, they usually had their way with the Safavids. Selim I’s invasion of Armenia in 1514 put a poorly-prepared Safavid army to flight, and in August of that year, an Ottoman force numbering 100,000 tracked down a Safavid army half that size at a place called Chaldiran, not far from Tabriz. It is probably also worth mentioning that a bunch of the Ottoman Janissary troops were armed with muskets, and their army was supported by 200 cannon and 100 mortars; the Safavids brought improved versions of their Parthian ancestor’s bows to the field, though they had such supreme confidence in their own horsemanship that they were actually the first ones to surge across the field, confident in their belief that sheer balls could overcome an otherwise hopeless technological and numerical disadvantage.

Ismail himself was wounded and nearly captured at the Battle of Chaldiran, and Tabriz fell shortly thereafter. Selim was forced to withdraw from his new trophy as winter set in, however, since the Safavids had retreated to the safety of the Persian highlands and the Turkish army was proving mutinously unwilling to go up after them. In the settlement which followed, enough land was ceded to the Ottomans that Tabriz became a pretty unsafe place to locate a capital – and it also established the boundary that still serves as the Iran/Turkey border today.

Ismail himself was wounded and nearly captured at the Battle of Chaldiran, and Tabriz fell shortly thereafter. Selim was forced to withdraw from his new trophy as winter set in, however, since the Safavids had retreated to the safety of the Persian highlands and the Turkish army was proving mutinously unwilling to go up after them. In the settlement which followed, enough land was ceded to the Ottomans that Tabriz became a pretty unsafe place to locate a capital – and it also established the boundary that still serves as the Iran/Turkey border today.

Pop Quiz:

1. After Chaldiran, the Safavids changed the official language of their empire from a Turkish dialect to Persian. Explain why the Safavids would go to such trouble.

2. Identify and discuss at least two reasons why the Safavids first moved their capital to Qazwin, a few hundred kilometers deeper into Persia than Tabriz, in the mid-16th century, and then to Isfahan, in central Iran, in 1598. Take in to consideration that Tabriz was being chronically captured by successive Ottoman sultans, and that Isfahan was a next-door neighbor to the ruins of Persepolis.

3. For a couple of centuries, the cities of Baghdad, Najaf, and Karbala repeatedly changed hands between the Safavids and the Ottomans. These cities are all sites of important Shi’a shrines. Is this a coincidence? Explain.

4. Consider the following: You are Ismail, and you have learned that your favorite wife was captured by Selim at Tabriz. He will sell her back to you, but at an outrageous price. As a proud Safavid king, do you:

A. Pay whatever ransom Selim demands; you love her

B. Refuse to give in to Ottoman demands

C. Die of a broken heart in 1524

D. B & C

(hint: “D” is correct)

5. Consider your answer to question 4 with regard to the impact of a story like this might have on national identity and – dare I ask – character? Explain your response.

Feudal theocracy tends to leave an impression

At the time of the Safavid and Qizilbash ascendancy to power in Persia, most of the population was Sunni, with significant-sized Sufi pockets here and there, which necessitated in the mind of Ismail I what one might nowadays cynically call “enhanced conversion techniques.” As noted at uccalgary.ca, Ismail’s policies may have had more to them than simply distinguishing Safavid Shiism from the neighboring Sunnis:

Considering the zeal with which he enforced conversion among his subjects, however, it is more likely that he was a devout Shi’ite himself, and he believed for religious, not political reasons, that his empire should embrace his faith exclusively. Unfortunately for Ismail, most of his subjects were Sunni. He thus had to enforce official Shi’ism violently, putting to death those who opposed him. Under this pressure, Safavid subjects either converted, or pretended to convert. It is nearly impossible to determine exactly how many truly converted, because virtually the entire population claimed to have converted, out of fear of the consequences. Still, it is safe to say that the majority of the population was probably genuinely Shi’ite by the end of the Safavid period in the 18th century, and most Iranians today are Shi’ite, although small Sunni populations do exist in that country.

Under Safavid rule, there was no distinction between the Shi’a religious aristocracy and the government. The Sunni leadership was killed or exiled, conversion became mandatory, and any practice of Sufism was banned upon penalty of death (alas, how quickly we distance ourselves from our roots…). Lands and money were doled out to Shi’a religious leaders who promised their loyalty to the Safavids and their increasingly intrigue-ridden corps of Redheads, and the Shah was held to be the divinely ordained leader of both the faith and the nation.

Under Safavid rule, there was no distinction between the Shi’a religious aristocracy and the government. The Sunni leadership was killed or exiled, conversion became mandatory, and any practice of Sufism was banned upon penalty of death (alas, how quickly we distance ourselves from our roots…). Lands and money were doled out to Shi’a religious leaders who promised their loyalty to the Safavids and their increasingly intrigue-ridden corps of Redheads, and the Shah was held to be the divinely ordained leader of both the faith and the nation.

The Redheads really were becoming a problem. They assassinated at least one shah, and their vakil – the satraps of their day – were as difficult for a weak shah to control as their predecessors had been for the Seleucid kings. Still, their participation in the military is the only thing that kept Iran free of Ottoman domination through the reigns of those same weak shahs, and some of their court intrigues – like the forced abdication of Shah Muhammad Khudabunda – had positive results.

Shah Abbas restores dignity – by the sword!

In the case of the above referenced resigning king, the positive result was the ascension of his son, Shah Abbas I, to the throne in 1587. He was only 16, but he learned fast: he lost a little territory in battle, and cut deals that gave up a little more, but by age 19 he attained peace with the Ottomans, and managed to maintain it long enough to buy some time to modernize Persia’s obsolete army. To do this, he sought the assistance of a British general named Robert Sherley.

Sherley helped to reorganize the Shah’s army along the European model, as the Ottomans had recently done to such devastating effect with their own. The Ghulams (“slaves”), who formed much of the cavalry, were conscripted Armenians, Georgians, and Circassians; from the Tfongchis and Persian peasantry were drawn the musketeers; and the Topchis manned the artillery. Against a backdrop of Shi’a religious fervor, anti-Sunni/Turk (and anti-Arab – there was still plenty of fighting in present-day Iraq) animosity, and a rising sense of Iranian identity and nationalism, Sherley and 14 compatriots lived in Persia for years, training an army; eventually the old Brit would assume the role of Persian ambassador to Christendom.

Back before the Englishmen arrived, Abbas had skillfully taken advantage of the death of Ivan the Terrible in Russia, by securing the fealty of several states in the southern Caucasus. Abbas wanted to use the reconstituted army that a decade of peace had bought him. The Uzbeks, who had established themselves south of the Oxus once again, were first on the list, and the cities of Mashad and Herat were re-conquered in 1598. He then turned his attention to Baghdad, which he took from the Ottomans (along with eastern Iraq and the Caucasus) by 1622, and next the Portuguese, from whom he captured Bahrain in 1602 and Hormuz (hat tip to the English navy) in 1622.

The Safavids had an unfortunate tendency to involve themselves in long, dragged-out wars; Baghdad and the plains of Iraq changed hands several times over the next 150 years.

Neither did Shah Abbas have any compunction about visiting atrocities upon those who resisted him: he ordered a general massacre of Bedarost and Mukriyan (reported by Eskandar Beg Monshi, Safavid Historian (1557-1642) in the Book Alam Ara Abbasi) and a massive forced relocation of thousands of Turks to northwest Iran in response to Kurdish moves toward independence.

In some repspects, Abbas was far sighted and cagey: he expanded Persian trade by cultivating relationships with the British East India Company and its Dutch counterpart/competitor, and since Persia sat astride the Silk Road, and since its people had perfected the art of carpet-weaving under Safavid rule, this made Iran a broker of highly lucrative luxury goods. In other respects, however, he was as short-sighted as a George Bush and self-destructive as a Richard Nixon – one can assume he was profoundly bummed when he found himself unable to leave a suitable heir to his throne, as he had executed one of sons and blinded two others for fear that they would assassinate him, only to have his other two potential heirs die before him.

Safavid fortress at the city of Bam

It’s all downhill from here

Isfahan under Shah Abbas was an almost magical place, a crossroads of the world and a city of immense wealth and creativity, but it concealed some serious flaws in its administrative structure. Ever since the founding of the dynasty, simmering conflicts between Iran’s two major ethnic divisions – the Redheads and the Ghulam-based army, and the ethnic Persian bureaucrats and religious aristocracy – had undermined Safavid efforts to fully unify their state. Think of it as the “men of the sword” versus the “men of the pen,” in which the pen-guys have a millennia-old tradition of administering their own lands no matter what foreign group held the title of ruler, and the sword-guys – being ethnically, linguistically, and historically completely different from the pen-guys – don’t give a rat’s ass about the non-martial traditions of the bureaucrats.

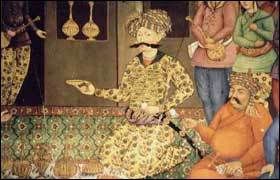

Serious Safavid decline began after the death of Shah Abbas II in 1666, but it was kind of like that Rome thing: it was an interlinked series of military defeats, economic decline, and impossibly decadent leadership that did them in, not a single, glorious conquest by the next folks in the historical line. They say that Suleiman I, reigning from 1666-1694, spent eight of those years in the harem, and that Shah Sultan Hussein (1694-1722) drank without cease. Indeed, Safavid art became famous for its semi-nudes and celebrations of lovers – which makes sense, given that Abbas and subsequent Shahs had taken advantage of Europe’s Renaissance by sending artists there to study – but it does strike this historianter as a little incongruous with my supposedly-contemporary perception of what a hardcore Shi’a theocracy would look like, culturally speaking. Something tells me we’re not going to be hearing Mohammad Khatami calling for a return of Safavid (or Qajar, for that matter)-style art anytime soon.

Europe was not the only foreign influence for Safavid Persia – in the late 17th century, they got quite chummy with the Ayutthaya dynasty of Siam – but foreign misadventures and missteps were more the general rule. They lost the Caucasus to the expanding power of Muscovite Russia (“we beat the Golden Khanate!”) and much of Afghanistan to Mughal India (“get a load of the tomb I’m building for my wife!”). Additionally, the Arabs of southern Iraq, the Uzbeks, and the Ottomans all ensured that the guys who drew the borders of Safavid maps enjoyed a decent sense of job security.

Europe was not the only foreign influence for Safavid Persia – in the late 17th century, they got quite chummy with the Ayutthaya dynasty of Siam – but foreign misadventures and missteps were more the general rule. They lost the Caucasus to the expanding power of Muscovite Russia (“we beat the Golden Khanate!”) and much of Afghanistan to Mughal India (“get a load of the tomb I’m building for my wife!”). Additionally, the Arabs of southern Iraq, the Uzbeks, and the Ottomans all ensured that the guys who drew the borders of Safavid maps enjoyed a decent sense of job security.

As is so often the case with imperial decline, the problems which plagued the rulers of Isfahan were often a result of their failing to have enough regard for their own history. For example, the books pretty clearly show that Afghan warlords respond poorly to forcible coercion, so it should come as little surprise to learn that when Shah Sultan Hussein ordered the eastern reaches of his empire converted to Shiaism, the tribes revolted. Still pissed a couple of years later, in 1722 the Afghans invaded Persia, sacked Isfahan, and spent the next twelve years rampaging around the Iranian countryside.

The Safavids never really recovered, though Safavid rulers seized the crown or were used as puppets by various warlords and minor dynasties seeking to legitimize their claims for decades to come. One of these rulers, Nadir Shah (r. 1736-1747), attacked and slaughtered in all directions, at one point capturing the Mughal capitol of Delhi before realizing that he’d conquered more territory than he could control. Before he left, though, he seized the literal seat of Mughal power, the Peacock Throne, and carted it back to Isfahan. Though the original was destroyed during the civil war that followed Nadir’s death, later rulers made various copies, and the throne of Iran itself became unofficially known as the Peacock Throne until the rise of the Ayatollahs in 1979.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Back in 1760, the Safavids were toast, and the torch of Iranian leadership passed to…

Karim Khan and the Qajars

Karim Khan Zand (1760-1779), who later adopted the title “Peasant’s Regent” as opposed to Shah, was a general under one of the last Safavid monarchs, the infamous Nadir Shah (a real burn-the-kingdom-to-save-it kinda guy). From the confusion of the Afghan invasion and the various grabs for power which followed, Karim Khan emerged victorious, and turned out to be exactly what Persia needed – to this day, he is viewed as one of the most just and benevolent rulers in Persian history. He stabilized the kingdom internally, established a capital at Shiraz, and smoothed over relations with the British by allowing the East India Company a trading post at Bushehr, in the southern province of Khuzestan. This last, especially, turned out to be a wise move (even given its oddly-portentous name and geographic placement), as this was a time when Britain had little interest in accumulating any more enemies.

So it was that while the American colonists were fighting at Cowpens and Yorktown, signing treaties in Paris, and marveling at the mess their Articles of Confederation created, a Qajar leader, Agha Mohammad Khan was reunifying Iran. Ethnically a Turkmen Azerbaijani, and politically the head of both the Qajar tribe and the southern province of Zand Persia, he reestablished Persian dominance through Georgia and the Caucasus. He’s also the guy that brought the capitol to Teheran, and initiated the Qajar Dynasty, which would rule Persia until 1925.

Agha Muhammad Khan himself only got to wear the crown of the Shah for a year (1796-1797) before being assassinated. His nephew, the ill-fated Fath Ali Shah, next ascended the throne, but soon found himself set upon by the Russians, who were engaging the British on a broad set of Asian fronts in what came to be known as the Great Game.

A nail-biter of a Colonial Era

It is instructive to note some of the context of Persia’s struggle to survive European imperialism. Here are a few items, in no particular order of importance:

- Military power: Russia forced Fath Ali Shah to sign the Treaty of Golestan, acknowledging the Russian annexation of Georgia and surrendering a large chunk of the traditionally-Iranian south Caucasus, in 1813. This means that the Czar was able to compel the Shah to sign this humiliating treaty at the same time as the majority of his army (presumably) was fending off the largest army Napoleon Bonaparte ever assembled. From this we can probably safely infer that Iran’s leaders were once again bringing horse archers to gunfights.

- Appeasing the bully: Russia came back for more in the 1820’s, and by 1828 had pounded the Iranians so badly that they signed the Treaty of Turkmanchai, in which Persia surrendered all claims north of the Aras River. This area now comprises Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan.

- Doing the dirty work: Fath Ali Shah’s grandson, Muhammad Shah, succeeded him in 1834. At the behest of the Russians, he launched two unsuccessful attacks on Herat during the next 15 years. This would later lead to the Brits carving from traditionally Iranian lands the state of Afghanistan, which was to serve as a buffer between Persia and British India. This was done under the guise of the Declaration of Paris of 1856, buried far beneath the “Bans Privateering” headline, which Nasser (see below) was forced to sign after the British launched an invasion out of Bushtehr.

- The just-in-time Great Leader: Nasser al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) had much in common with the leaders of one those few other non-Euro/American nations that managed to survive the late 1800’s more or less intact. Though he fought like Santa Anna, he ruled like Porfirio Diaz – though with a strong undercurrent of Benito Juarez – and he had a bit of the Meiji about him, too: he modernized Iran’s postal and banking systems (there’s irony for you, considering the Persian roots of both), established railroads, and is said to be the first Iranian ever to be photographed.

- Yeah, but: Nasser al-Din Shah ruthlessly persecuted religious dissidents like the Babis and Bahais, and this persecution only increased after a failed assassination attempt by a deranged Babi in 1852. He also spent much of Persia’s treasury on his own lavish lifestyle, visiting Europe and running his palace and harem in the decadant style of the Old School.

- The National Hero: Amir Kabir (“Great Ruler”) was the title given Nasser’s prime minister for the first 2½ years of his reign. Amir Kabir did it all: balanced a bankrupted treasury, overhauled the government, established the rules and forms of modern Farsi prose writing, and laid the groundwork for the establishment of Iran’s first modern university, the Dar ol Fonoon in Teheran. For his efforts, Nasser perceived him as a threat, and had him strangled in exile in 1851.

- A Stunning Assassination: Shocked the easily shocked on May 1, 1896, when a follower of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (a wild-eyed moonbat who had the temerity to teach at his madrassah that the key to Muslim unity lay in the rule of law and in constitutional government – the nutcase even included jurisprudence in the curriculum, alongside philosophy, recitation, and mysticism!) killed Nasser while he prayed in a mosque. Nasser was shot with a gun so ancient and rusty that the Shah might have survived had he been wearing a thicker coat, but he departed this world with the poignant, though possibly-menacing, promise, “I shall rule differently if I survive.”

After the watershed

Mozaffar al-Din Shah (1896-1907) was one of those weak, entitled, and highly disconnected rulers that seem to pop up as empires collapse (not that we modern Americans would know anything about that). He borrowed money from Russians, then spent it on trips to Europe. He granted trade concessions in exchange for bribes, and turned a deaf ear to complaints that the Russians were exerting undo influence over his policies.

His failure to protect his supporters – mostly clerics and merchants – from reformist mobs in 1906 led them to seek sanctuary first in mosques and temples, then in the courtyard of the British legation in Teheran (10,000 were said to have sought refuge there). Mozaffar had reneged on a promise to form a new “house of justice” (a consultative assembly), and now the mob was calling him out. He finally relented in August, when he promised a constitution, and October, when the Majles, an elected parliament, convened for the first time. The Majles had broad representative powers, and the right to assemble the Shah’s cabinet for him. Dejected, Mozaraff signed the necessary documents to make himself a constitutional monarch on December 30, 1906, and died five days later.

Under Muhammad Ali Shah (1907-1909), the Russians did everything they could to restore the monarch to his full absolutist powers. The Shah even went so far as to use his brigade of Russian-officered Persian Cossack cavalry to bomb the Majles before ordering the constitution suspended. This provoked reaction in Tabriz, Isfahan, and Rasht, and in July, 1909, marchers from Rasht and Isfahan entered Teheran and deposed the shah (who went into exile and Russia) and reinstated the constitution.

Ahmad Shah (r. 1909-1925), who ascended the Peacock Throne at the tender age of 11, would prove to be the last of the Qajar monarchs. The deck was stacked against him – for example, the division of Persia into China-style spheres of influence under the Anglo-Russian Agreement of 1907 left the throne open to challenges like the one faced when Morgan Shuster, an American in the employ of the Persian government, tried to tax the Russians and wound up with a bunch of tribal chieftains surrounding the Majles and suspending the constitution yet again – but he didn’t help matters much by retaining a 17th-century view of the world and his place in it.

Ahmad Shah (r. 1909-1925), who ascended the Peacock Throne at the tender age of 11, would prove to be the last of the Qajar monarchs. The deck was stacked against him – for example, the division of Persia into China-style spheres of influence under the Anglo-Russian Agreement of 1907 left the throne open to challenges like the one faced when Morgan Shuster, an American in the employ of the Persian government, tried to tax the Russians and wound up with a bunch of tribal chieftains surrounding the Majles and suspending the constitution yet again – but he didn’t help matters much by retaining a 17th-century view of the world and his place in it.

Under the pleasure-loving, generally incompetent reign of Ahmad, Iran found itself occupied by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops during the First World War, and divvied up between France and England by the Sykes-Picot Agreement as the war wound down and the spoils of the Central Powers’ defeat were apportioned. He was finally usurped in a coup by Reza Khan Pahlavi in 1921, and deposed formally by the Majles in 1925. That final insult had to be delivered in abstentia, as the last Qajar monarch had already fled to the decadence of exile in Europe.

Still to come…

The final installment(s) of what has turned out to be (at least) a six-part series should be ready to post next Sunday night, regular bat-time, regular bat-channel – again, sorry about the long delay in getting this one out. After that…well, let’s put it this way: me and Swordsmith have a convention and a Crusade of Kings (as it were) that we’re gonna love telling you about…

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

7 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

Fortunately, things in both the meteorological and work worlds are looking a little more conducive to regular posting than they’ve been recently – should be able to get close to wrapping this series up next week. Thanks again to all who’ve been sticking with it!

and proves how little anyone of our “leaders” know anything about this great region and the complexities.

The decision, and the broken heart & death…I know the original california indians, when removed from the coast, literally died from broken hearts…but they were forced to leave the land they loved or face certain death.

Thanks for the links!

Once again you tested my powers of projecting pronunciations of unknown languages (to me) and gently twisted my tongue into submission.

Usually I offer kudos (and pistachios for Persia) at the orange site but tonight seemed like a fair evening to wander over here.

One day we’ll have this in video, with maps unscrolling and territories defining and changing and reforming, visual and oral history all at once, with wisps of language and art and weaponry filling in the echoes. But for now this was just a fine romp.

Thanks once again, Moonbat. History will wait for you.