One would think that a person who has lived through as much history as John McThuselah would know a bit more about it, but as we are all too painfully aware, historical savvy isn’t exactly a wingnut strong suit. It’s thus sorta-understandable – even as it remains completely unforgivable – that Angry Gramps would be unable to distinguish between Sunnis and Shias, Arabs and Persians, or really, anyone east of the Ural Mountains. To the bomb bomb bomb, bomb bomb Iran set, “they” are all the same anyway, so any historical evidence that might indicate an outcome (of say, an invasion) other than their liberators-and-roses predictions can be safely disregarded.

Thankfully, we here in the reality-based community know better. Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, for a look at Iran in the 20th century – and hopefully a slightly better explanation for why the US government is not particularly loved in that part of the world than that old patriotic pabulum, “they hate us for our freedoms.”

Historiorant: When the first edition of this series aired two years ago, there was no Cave of the Moonbat, nor historioranting, nor somewhat-standardized format for what goes on here. All those things developed while I was cutting my teeth in the commentless void, as witnessed by the slightly-edited intro to the first edition of this diary (pub. Saturday, March 4, 2006), included here both for posterity’s sake and to bring us up to speed on the story thus far:

At the conclusion of our last Moonbatological historant (so much for Tuesday or Wednesday, eh? Sorry!), we left the emerging modern state of Iran in flux. The shahs of the Qajar dynasty (est. 1796) had suffered the ignominy of having a constitution foisted upon them, and by late 1906, the Russians and the British were carving Persia up like a roast for a sphere-of-influence banquet to which the doddering Ottomans had not been invited. Finally, a nascent nationalist movement was working itself into a lather over the occupation of sovereign Persian territory by foreign imperialists and the robe-kissing decadence of their own Qajar government. Persia’s status as colony-to-be was further cemented by the ascension to the throne in 1909 of the 11-year-old Ahmad Shah, who was (being 11) utterly incapable of dealing with the demands of constitutionalist reformers, nor of resisting the Anglo-Russian alliance that invaded his country for “stabilization” purposes in 1911.

Saved by the guns…sort of

With the monarch in their pocket, the only threat faced by the Russians and British came from the constitutionalists (who tended to be pretty nationalistic) in their stronghold of Tabriz. The task of taking the city fell to the Tzarist forces, and take it they did – with a bloody vengeance. The Russians visited horrible atrocities upon the people of that town, with a deliberation and ruthlessness that gives we Western dilettantes in the long, complex history of the Iranian people a laid-bare, sterling example of the kind of event that sears itself into a nation’s memory and is neither forgiven nor forgotten for centuries:

The suppression of the nationalist uprising by Russians was followed by a wholesale massacre of the constitutionalists in Tabriz. Sigat al-Islam, one of the most respected religious pontiffs in Iran, was arrested and ordered to sign a declamatory document that Russian suppression of the constitutionalists was for “stability” and “normalisation” purposes. The pontiff refused to obey and was therefore flogged and finally hanged in the public market square on the most respected and observed religious day in the Iranian calendar, Ashura. This specific Russian savagery aroused anger all over the world among Muslims against the Tzars.

For reference, see Iran September 7, 1917 Chehrenoma March 4, 1912; and E.G. Browne, The Reign Of Terror at Tabriz. London: Taylor, Garnett, Evans and Co. 1912, pp.1-15.

There was precedent for this sort of behavior; one only had to look at how India had fallen into the Empire’s grasp and how China had been brought to heel. It seems pretty clear that Persia was on its way to being divided up and annexed outright by the Brits and the Russians (a bipolar alliance if ever there was one). They probably would have gotten away with it, too, if it hadn’t been for the distraction-of-epically-massive-proportions that was the 1914 eruption of the Great War, which transpired when the Shah of Persia was 16 (in high school terms, a sophomore or a junior). Thus, as Russia mobilized on behalf of her erstwhile little brother Serbia, as Rasputin whispered sweet weirdnesses in the Tsarina’s ear, and as the bulk of the British army was being thrown into the carnage of the First Battle of the Marne, Ahmad Shah announced his nation’s neutrality – and his people braced once more to play host to the battlegrounds of superpowers.

The Russians took control of the northern provinces, and on Persian territory fought with the Ottomans. On the other side of the Zagros, the British South Persia Rifles, commanded by Sir Percy Sikes, occupied the provinces of Isfahan and Shiraz, and there alternated between fending off German and Turkish attacks and helplessly watching their countrymen’s disastrous invasion of Iraq wither away in a siege they were powerless to lift. All’s well that ends well, though – another Sykes (this one with the first name of Mark) went on to negotiate the British side of the Sykes-Picot Agreement with France in 1916, and effectively was given a free hand in drawing the map of the post-war Middle East, a map only slightly modified for the following year’s Balfour Declaration.

The Russians took control of the northern provinces, and on Persian territory fought with the Ottomans. On the other side of the Zagros, the British South Persia Rifles, commanded by Sir Percy Sikes, occupied the provinces of Isfahan and Shiraz, and there alternated between fending off German and Turkish attacks and helplessly watching their countrymen’s disastrous invasion of Iraq wither away in a siege they were powerless to lift. All’s well that ends well, though – another Sykes (this one with the first name of Mark) went on to negotiate the British side of the Sykes-Picot Agreement with France in 1916, and effectively was given a free hand in drawing the map of the post-war Middle East, a map only slightly modified for the following year’s Balfour Declaration.

Russia and Great Britain together fended off German and Turkish propaganda campaigns, and Persia was made part of a complex set of power-sharing agreements that were to go into force after the war (Russia gets Constantinople in exchange for accepting British dominance in Teheran, that sort of thing). That all ended, of course, when Lenin showed up and prodded the Russians to share with one another a little more.

With the rise of the Bolsheviks came a major shift in Russian foreign policy, and to prove the point, they withdrew all Russian troops from Persia in favor of assisting anti-imperialist indigenous forces. Britain, once a partner, was now an enemy as the Reds called upon Persians to cast off the yoke of colonialism and refashion their country as a worker’s paradise. The Brits, ever sensitive to vacuums, rushed into the recently-abandoned northern provinces and established bases that were subsequently used by White Russian troops to launch attacks into the Red’s southern flank during the Russian Civil War. From the British perspective, it made sense to help their former allies kill one another, as it was becoming quite evident to the British that Persia was sitting atop a lot of oil.

So it was that the British sought to continue playing the 19th-century imperialism game, using the standard mix of thinly-veiled belligerency, sovereignty-sucking economic tendrils, and plain-old self-righteous White Man’s Burdenism. Under the cagey leadership of England’s foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, the Brits paid off a handful of prominent Iranians (including the prime minister, Vosuq od-Dowleh) to ensure support for the Anglo-Persian Agreement of 1919. Some of the provisions it contained sound like they came straight out of a Powell/Rice State Department:

It promises to “supply, at the cost of the Persian government, the services of whatever expert advisers may, after consultation between the two governments, be considered necessary for the several departments of the Persian administration. These advisers shall be engaged on contracts and endowed with adequate powers, the nature of which shall be the matter of agreement between the Persian government and the advisers.”

“For the purpose of financing the reforms indicated in clauses 2 and 3 of this agreement, the British government offers to provide or arrange a substantial loan for the Persian government, for which adequate security shall be sought by the two governments in consultation in the revenues or the customs or other sources of income at the disposal of the Persian government. Pending the completion of negotiations for such a loan the British government will supply on account of it such funds as may be necessary for initiating the said reforms.”

“The two governments agree to the appointment forthwith of a joint committee of experts, for the examination and revision of the existing customs tariff with a view to its reconstruction on a basis calculated to accord with the legitimate interests of the country and to promote its prosperity.”

Had od-Dolweh been the only person the Brits had to please, this odious piece of diplomacy might have become law, and Persia a British protectorate. Fortunately for the Iranians, they had in place a parliamentary system with the cajones (anybody know the Farsi word for “balls?”) to tell the PM to piss up a rope, and the Majles refused to ratify the Agreement. The nation remained in a state of political flux until February, 1921, when a dashing Persian Cossack Brigade officer named Reza Khan Pahlavi, with the help of journalist Sayyid Zia ad Din Tabatabai, organized a coup d’etat and seized power in Teheran.

Meet the Pahlavis

Over the next four years, cavalry general-cum-war secretary consolidated his power base and negotiated the removal of foreign troops from Persian soil. In 1925, the Majles made the deposition of the last Qajar monarch official (the guy was already in exile in Europe anyway), and the newly-appointed leader changed his name to Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Over the next four years, cavalry general-cum-war secretary consolidated his power base and negotiated the removal of foreign troops from Persian soil. In 1925, the Majles made the deposition of the last Qajar monarch official (the guy was already in exile in Europe anyway), and the newly-appointed leader changed his name to Reza Shah Pahlavi.

The new Shah was a dyed-in-the-wool nationalist, one of a new breed of leaders (which also included Kamal Ataturk and Haile Selasie) that frustrated would-be empire-builders in the West. He revoked the special privileges enjoyed by foreigners, encouraged domestic production by instituting a protective tariff, and changed the regulations under which oil companies operated so as to secure more of their revenue for his treasury. He was the driving force behind the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway and over 20,000 km of roads, founded the University of Teheran, and set up programs encouraging college students to attend school in Europe. Oh, and in 1935 he changed the official name of the country to “Iran,” though it took a few years before the name stuck.

Much like Ataturk in neighboring Turkey, Reza Shah Pahlavi was a secular ruler. He opened educational institutions (and all public places) to women, strengthened the secular state courts, and reduced the role of religious institutions upon daily life. He also mandated the wearing of western style attire – though accented with a distinctive peaked cap – for men, and in 1935 required women to discard their veils.

So far, so good – but you’re probably thinking that there had to be downside, right? Well, there was:

For starters, mandating the rejection of traditional, indigenous dress and proscribing personal expressions of faith may have helped with the whole western-style industrialization thing (or not), but it all sounds a little Carlisle Indian School to this historioranter. His attempts to re-align the culture of his country sometimes grew violent: in 1936, the Shah’s troops violated the sanctity of the shrine of Imman Reza in Mashad by killing dozens of protesters who had gathered to express dissatisfaction with the latest round of reforms.

The Shah also had a quick-tempered tendency to use his army to pacify, disarm, and resettle rebellious tribes and warlords, which in and of itself isn’t that uncommon, but history (plus, I hope, the last six episodes of this series) pretty clearly shows that those guys – the heirs to the satraps and tribespeople that have vexed every central authority in Iran since the Seleucids – don’t go down easy. Reza, the son of an officer and a Cossack since the age of 15, was inclined to use force to get his way, which begat more violence from the rebellious tribes, which begat reprisals, which begat more reprisals, and so on and so on.

The Shah also had a quick-tempered tendency to use his army to pacify, disarm, and resettle rebellious tribes and warlords, which in and of itself isn’t that uncommon, but history (plus, I hope, the last six episodes of this series) pretty clearly shows that those guys – the heirs to the satraps and tribespeople that have vexed every central authority in Iran since the Seleucids – don’t go down easy. Reza, the son of an officer and a Cossack since the age of 15, was inclined to use force to get his way, which begat more violence from the rebellious tribes, which begat reprisals, which begat more reprisals, and so on and so on.

Beginning in 1933, Iran developed close ties with Nazi Germany, eventually becoming one of the Reich’s largest trading partners. Though this policy was pursued in part to reduce British influence on Iran’s economy – most of the royalties on the 200,000 or so barrels a day Iran was pumping went to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company – the net result was that Germany was Iran’s largest trade partner in the late 30s.

Historiorant/Please Don’t Gitmo Me Disclaimer: Not that there’s anything wrong with trading with Nazis, of course – our own history has shown that a US Senator can coddle Hitler and still have both his son and grandson grow up to defile the White House in their own “right”

Much of the wealth generated from all this oil trade went straight into the Shah’s personal accounts regardless of who was doing the buying, and he amassed considerable tracts of land even as conditions among the peasantry worsened. For all his paternalism, he was a totalitarian dictator; by the late 30s, dissatisfaction with the Shah’s rule was growing – it might have even led to a revolt at some point, had it not been for the Second World War.

Planting a neutral flag on strategic ground

When Hitler shocked and awed Poland in September, 1939, Iran decided to pursue the difficult course of being neutral and strategically important at the same time. The Shah pissed off the British by not responding to their “reasonable” request to expel all German nationals from Iran, but when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, things boiled down to ultimatums very quickly. Churchill demanded that Iran allow the British to move supplies across Iran to assist the Soviets, a move which the Shah regarded as a violation of neutrality, and thus sovereignty.

He would not be told what to do, and he got invaded for it. On August 26, 1941, the British and the Soviets launched simultaneous troop surges from the Persian Gulf (there’s that old trading colony in Khuzestan again), Iraq, and the northwestern frontier. Within weeks, Iran had fallen under Allied control, and on September 16, the Shah was forced to abdicate in favor of his son. He was brought by the British first to Mauritius, then to South Africa, where he died in 1944.

Mohammad Reza Shah assumed the throne at the age of 22, and in January, 1942, concluded a tripartite treaty with Great Britain and the Soviet Union that extended nonmilitary assistance to the Allies; over the course of the war, more than 5 million tons of US and British war supplies made their way through Iran to an embattled Soviet Union. In 1943, Iran declared war on Germany (eligibility for UN membership: check!), and later that year played host to Churchill, FDR, and the Man of Steel himself.

These were tumultuous years. Foreign troops brought out the nationalism in folks, and the Soviet-backed Tudeh party organized workers and agitated for economic reform. This group would be a driving force behind the failed attempt by the Soviets to create client states out of Iranian territory in the form of an autonomous republic in Azerbaijan, and shortly thereafter, the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad in January, 1946. US, British, and UN pressure led to a withdrawal of Soviet troops from those countries, and later that year, the Shah’s army recaptured them and sent their leaders into exile. The Soviets lost more ground (in the figurative sense) in 1947, when Iran received a military aid package and advisory group from the United States.

And the Tudeh? While they did enjoy a brief stint during which the Shah was obligated to have three Tudeh members in his cabinet, this arrangement fell apart over a tribal revolt in the south. Though they agitated, the Tudeh would never again hold such influence. In 1949, after a Tudeh member was blamed for an assassination attempt on the Shah, the party was banned and its leaders fled into exile or were arrested.

Looking for support in all the wrong places

The first few postwar years weren’t so great for the new Shah, owing largely to the growing influence of longtime dissident Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq. Arrested and imprisoned for thought crimes during the reign of the young leader’s father, Mosaddeq became a member of the Majles in 1941 and quickly gained notoriety for his nationalistic, anti-British-oil-company rants. The Communists supported him, too, which would eventually draw American suspicion.

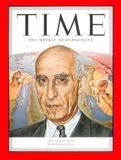

By 1951 – when he was named Time’s Man of the Year – Mosaddeq had enough support that the Shah was pressured into making him Prime Minister. The eccentric, European-educated lawyer quickly set about gathering a power base, and just as promptly pissed off the British by expropriating their oil fields (the Brits responded with a crippling economic and naval blockade). He went so far as to attempt to wrest control of the army from the Shah in 1952, and when the Shah rejected Mosaddeq’s demands, the minister resigned – only to be reinstated in a wave of populist riots.

By 1951 – when he was named Time’s Man of the Year – Mosaddeq had enough support that the Shah was pressured into making him Prime Minister. The eccentric, European-educated lawyer quickly set about gathering a power base, and just as promptly pissed off the British by expropriating their oil fields (the Brits responded with a crippling economic and naval blockade). He went so far as to attempt to wrest control of the army from the Shah in 1952, and when the Shah rejected Mosaddeq’s demands, the minister resigned – only to be reinstated in a wave of populist riots.

It went to his head. He bypassed the Majles with a public referendum on its dissolution, but still had enough accumulated political capital that when the Shah attempted to dismiss him in August, 1953, his supporters took to the streets. After negotiating the details of what would become known as Operation AJAX with US operative Kermit Roosevelt (grandson of Teddy), the Shah pulled a pre-arranged Darius and fled to Rome, while U.S. and British intelligence agents actively supported the royalists in the street battles. The coup succeeded when royalist tanks appeared in the capital and shelled the prime minister’s residence. Mosaddeq surrendered on August 19, 1953, and would spend three years in prison and eleven more under house arrest before his death in 1967. The Shah returned triumphantly from bravely running away, and once again planted his royal ass upon the Peacock Throne.

Weird Historical Sidenotes: One version of the AJAX story has the U.S. deploying its newly-minted CIA because the British had fed Ike faulty intelligence regarding the likelihood of Mosaddeq’s shift to a more Kremlin-friendly foreign policy. Considering current circumstances, there’s a little irony in that.

The other odd sidenote concerns who was holding the Shah’s trembling hand as he was led through the whole burial-of-democracy process – the two most intimately involved were the monarch’s twin sister Ashraf and General H. Norman Schwartzkopf, father of the “Stormin’ Norman” who, despite his obvious un-Patraeusness, nevertheless displayed an ability to bring a successful conclusion to a war in the Middle East.

Also worthy of note is this video, promoting All the Shah’s Men by Steven Kinzer, that made an appearance on Huffpo a couple of months ago:

The Shah we all sort of remember

The Shah had nearly lost control of his country, and he had the US to thank (and thank, and thank) for getting it back. Still, being seen as a toady of foreigners is a dangerous way to live in that part of the world, and the Shah’s close ties with Washington fueled a smoldering nationalist discontent throughout his nearly 40-year reign. He also created discontent by bungling a couple of rigged elections and by running through a series of prime ministers (though one stalwart lasted 12 years). The religious leaders were never too happy with him, either, but they had been pissed at being marginalized since the fall of the Safavids; even the eternal outsider Mosaddeq never felt the need to court them, preferring to rule in a profoundly secular manner.

But the Shah had big ideas, and he did accomplish some pretty impressive things. With US backing and hardware, he modernized the army that the ayatollahs would eventually take to war against Saddam. In 1963, he sponsored a broadly popular referendum (even if the vote wasn’t the reported 99% in favor) on land reform, as well as a huge literacy project – even if there had recently been large-scale riots and a general crackdown on opposition parties – as part of his “White Revolution.” He later extended suffrage to women.

But the Shah had big ideas, and he did accomplish some pretty impressive things. With US backing and hardware, he modernized the army that the ayatollahs would eventually take to war against Saddam. In 1963, he sponsored a broadly popular referendum (even if the vote wasn’t the reported 99% in favor) on land reform, as well as a huge literacy project – even if there had recently been large-scale riots and a general crackdown on opposition parties – as part of his “White Revolution.” He later extended suffrage to women.

Like so many prior rulers of his land, the Shah began to get Cyrus envy. In 1967, he angered people at all levels of Iranian society by adopting the titles “King of Kings and Emperor of Iran” and “Light of the Aryans,” while styling his wife, Farah Diba, “Empress.” It was things like this that allowed the religious leaders (some of whom, like the Ayatollah Khomeini, were in exile) to whip up anti-secular fervor among conservatives, while students began to organize around more nationalist lines.

But the Shah pressed ahead. In 1971, he televised worldwide an extravaganza celebrating the 2500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great. Trouble was, the show was mostly for foreign heads of state, and Iranians resented that very few of their countrymen had been in attendance at this self-indulgent lovefest. The Shah kept running with that theme in 1976, when he decreed the use of a new “imperial” calendar that started with the Achaemenian dynasty. Since this could pretty easily be interpreted to be anti-Islamic, the Shah was unwittingly empowering his detractors by driving more and more “sensible” folk into their camp.

The loving touch of the iron fist

To maintain order, the Shah became increasingly autocratic. He utilized his SAVAK secret police to hunt down, interrogate, and otherwise disappear those who spoke out against his rule, and these tactics in turn gave rise to a more organized resistance. Two main organizations emerged: the Marxist Fadayan and the Islamist Mohajedin. Both used similar tactics (bombings and assassinations, mostly, with the odd attack on police stations thrown in), but did not present a unified opposition front, as they had vastly different goals for what would come after the Shah. The Fadayan launched the first guerilla strike against the Shah in February, 1971, with an attack on an Imperial Gendarmerie at the outpost of Siahkal, deep in the forests near the Caspian Sea. Over the next 8 years, 341 guerillas would die in actions like this or as a result of being captured by the Shah’s forces, while hundreds more were imprisoned for long terms or driven into exile.

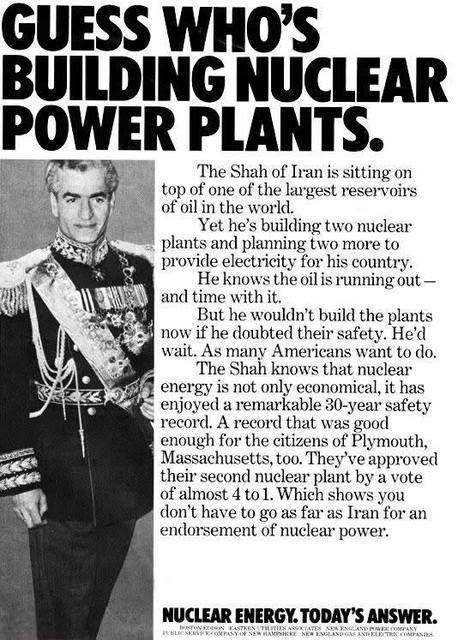

Weird Historical Sidenote: Of course, back in the Shah’s day, the good folks at the top of patriotic outfits like Boston Edison and a coalition of New England Gas and Electric Companies had a slightly different outlook on the splitting of atoms in Iran:

The Shah ran his economy into the ground in the 1970s, squandering the huge oil profits on Western toys of destruction – Nixon once offered the Shah the opportunity to purchase any conventional weapon in the US arsenal “in sufficient quantities to defend Iran.” To make good by his people, the Shah nationalized all private secondary schools and announced free secondary education for all Iranians. He nationalized other stuff, too – like unoccupied houses – for the public benefit, and he forced industrialist to sell 49% of the ownership of their companies to their employees.

But a badly implemented program is sometimes worse than none at all, and the Shah’s expensive new entitlements caused significant discontent. The nationalists pointed out that the Shah had done nothing to address the fact that there were around 60,000 foreigners (45,000 of them American) in Iran by the late 70s, and that decadent Western culture was spreading to the furthest reaches of the country, eroding traditional Iranian values along the way. Proponents of basic freedoms decried the Shah’s establishment of a single-party state in 1975, and his policies were starting to attract the attention of Amnesty International and other nosey, anti-torture types like that.

Things went from bad to worse for the Shah with the election of Jimmy Carter in the United States. After taking office in 1977, Carter made an issue of the human rights of the countries with which the US had relations, and there were a lot of skeletons in the Shah’s closet (in this case, a more literal allusion than usual). The Shah was obliged to release political prisoners, reign in his torture-hounds, and tone down his rhetoric.

The relaxation of oppression allowed anti-royal forces to organize, and political parties were reborn. Educated professionals wrote open letters to government officials demanding a return to the values of the constitution, and a war of eloquence versus propaganda began in the nation’s media.

Revolution…coming to a teevee near you!

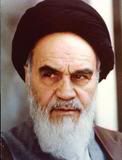

War of the more standard sort broke out at Qom – a profoundly religious city – in January, 1978, in response to a government-inspired article in a popular magazine which suggested that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had been verbally sniping at the Shah from exile in Baghdad, was far less pious than he claimed, and possibly a British agent, to boot. The over-the-top swift-mosquing led to further rioting and reprisal at Tabriz in February; by summer, rioting was widespread. The Library of Congress says this about the protests of 1977 and 1978:

The cycle of protests that began in Qom and Tabriz differed in nature, composition, and intent from the protests of the preceding year. The 1977 protests were primarily the work of middle-class intellectuals, lawyers, and secular politicians. They took the form of letters, resolutions, and declarations and were aimed at the restoration of constitutional rule. The protests that rocked Iranian cities in the first half of 1978, by contrast, were led by religious elements and were centered on mosques and religious events. They drew on traditional groups in the bazaar and among the urban working class for support. The protesters used a form of calculated violence to achieve their ends, attacking and destroying carefully selected targets that represented objectionable features of the regime: nightclubs and cinemas as symbols of moral corruption and the influence of Western culture; banks as symbols of economic exploitation; Rastakhiz (the party created by the shah in 1975 to run a one-party state) offices; and police stations as symbols of political repression. The protests, moreover, aimed at more fundamental change: in slogans and leaflets, the protesters attacked the shah and demanded his removal, and they depicted Khomeini as their leader and an Islamic state as their ideal. From his exile in Iraq, Khomeini continued to issue statements calling for further demonstrations, rejected any form of compromise with the regime, and called for the overthrow of the shah.

Things were already sucking for the Shah when in August, a fire in a crowded movie theater in Abadan killed 400 people. Though there is evidence that points to arson on the part of religiously motivated students, the opposition successfully spread a rumor that SAVAK agents had been responsible, and the Shah was obligated to replace his prime minister with someone a bit more conciliatory. He appeased the religious reformers by shutting down casinos, releasing imprisoned clerics, revoking the silly/insulting imperial calendar, and dismissing followers of the Bahai faith from all judicial and public offices (the ayatollahs have a special hatred for the Bahai, whom they view as heretical for failing to regard Muhammad as the last of the God’s prophets).

It was good ass-kissing, but not good enough. When Ramadan ended on September 4th, the 100,000 or so people who had turned out for public prayers began to demonstrate. For two days, the clashes grew more violent and the demands more strident. On the night of September 7-8, the Shah declared martial law, and the following day, at Teheran’s Jaleh Square, his troops opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators. The government said 87 were killed, but the number is almost certainly higher.

It was the screw-up that would galvanize his opposition. After “Black Friday,” even the moderates abandoned the Shah wholesale. In October, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, President of Iraq (playing the role of Cheney in Bakr’s administration: Saddam Hussein) wearied of Khomeini’s rabble-rousing and booted him out of the country. With much media fanfare, he established his new base in Paris.

The modern communications system available in Europe, coupled with the West’s open borders and free-flowing information, allowed Khomeini to take a much more hands-on approach than had been possible from Baghdad. He coordinated things via banks of multi-line telephones, and people that he heretofore hadn’t been able to meet face-to-face were able to visit him at his new headquarters. Among these was the leader of the powerful National Front party, who agreed to throw his support to Khomeini’s calls for overthrow with the promise that the country that would result would be both “democratic and Islamic.”

The modern communications system available in Europe, coupled with the West’s open borders and free-flowing information, allowed Khomeini to take a much more hands-on approach than had been possible from Baghdad. He coordinated things via banks of multi-line telephones, and people that he heretofore hadn’t been able to meet face-to-face were able to visit him at his new headquarters. Among these was the leader of the powerful National Front party, who agreed to throw his support to Khomeini’s calls for overthrow with the promise that the country that would result would be both “democratic and Islamic.”

Strikes crippled the economy, and the demonstrations grew in intensity. On November 5th, the Shah addressed the nation, saying he had heard their “revolutionary message” and that he would work to make up for past mistakes – he just needed a little time. As a show of good faith, he allowed the arrest of 132 officials (including a former SAVAK chief and several cabinet ministers) and released more than 1000 political prisoners. He also replaced his appeasement-oriented prime minister with the commander of the Imperial Guard.

Sensing blood in the water, Khomeini moved in for the kill, demanding further protests and decrying the Shah’s promises as worthless. The test came when the Shah chose not to use force to break a strike of government workers, and strikes resumed among emboldened laborers in other industries, bringing the economy to a standstill. Meanwhile, clashes between police and demonstrators had become a fact of daily life. Hundreds of thousands of protestors marched in opposition to the Shah’s rule on December 8th to mark the Shi’a month of mourning.

It was enough to compel the Shah to explore his options with the other side, and he tried and failed to cut a deal with the most prominent National Front leader, the one who’d visited Khomeini. At the end of December, he did manage to convince another National Front leader, Shapour Bakhtiar, to form a government, but only on the condition that the Shah leave the country. Bakhtiar won a vote of confidence in both houses of the Majles on January 3rd, 1979; two weeks later, on January 16th, the Shah announced that he would be taking a short trip overseas.

The Peacock Throne, and the 2500-year tradition of Persian royalty, had come to an end.

Historiorant:

…As must this diary, I’m afraid. It’s getting a little long, and there’s still another government to topple, hostages to take, a theocratic state to establish, a war to fight, and a new world order with which to tangle. Guess I’ll have to bow to the inevitable, and with apologies to those who value brevity in their drive-by histories, announce that I’ll be serving up History for Kossacks: The Ayatollahs, next week.

In other Cave news, be sure’n tune in two weeks from tonight (same bat-time, same bat-channel) for an important – to me, anyway 😉 – announcement regarding the series that followed the Persia one back in the earliest days of my DKos writing career. Here’s a hint: The Crusaders are coming! The Crusaders are coming!

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

5 comments

Skip to comment form

on Iran. Very well done.

Here’s something, somewhat related, from an essay I once started by never did complete. Possibly it would serve as a complement to your essay.

Now I must go read all of it.

Truly fantastic.