Lately it’s become apparent to some of us that if one desires to see one’s diary reach the rec list, one’s chances are greatly improved if the title includes a hint of conversion to Obamaism, a pillorying of Hillary, or the old stand-by, BREAKING!!! Now, by nature, historioranters don’t get to shout “breaking” all that often, but since you all seem to have abandoned Mike Gravel, and have said everything that could possibly be said about Barrackemiah and/or Billary, I’m left with little choice but to pander like Senator Clinton at a Great Silent Majority rally.

So join me, if you will, just outside the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll be scanning the skies, on the lookout for a school-bus-sized piece of space junk that NASA tells us (well, told us – the subject of this story broke literally and figuratively between 1973 and 1979) could crash/land almost anywhere on Earth. Perhaps in our observations, we’ll even get a glimpse of that rarest of celestial phenomena: A presidential candidate with a viable, workable, ambitious space policy.

In space, all warriors are cold warriors.

– General Chang

When you think about it, there aren’t all that many historical eras to which we can assign an exact starting date. At what point, for example, did the Cold War begin? Was it with the bombing of Hiroshima and/or Nagasaki, the assigning of Security Council seats at the UN, the start Berlin Blockade, or some other geopolitical event of similarly enormous import? The debate will likely rage far longer than the one about whether or not the presidency of George W. Bush ever rose to the level of “mediocre.”

Fortunately for our purposes tonight, the Space Race has a more precise origin: October 4, 1957. It was on that date the Soviet Union flung the 184-pound Sputnik I into orbit from the site that would one day be known as the Baikonur Cosmodrome, located in what was then called Kazakh SSR. Sputnik had an effect in the United States that could only be called alarming – President Eisenhower was obligated to take such non-Republican measures as founding NASA and working to pass the National Defense Education Act of 1958 to try to catch up in a race the US was now clearly losing.

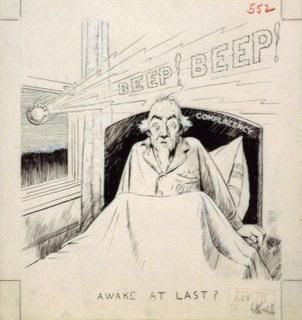

Sputnik was a direct assault on the complacency that Americans tend to consider our birthright, as shown in this depiction of Uncle Sam being startled awake from what he probably hopes was a bad dream. Alabama Senator Lester Hill summed up the surprise (and a bit of the “how-the-hell-did-they-get-in-front-of-us?” anger) that is prevalent in the bloviations of the time:

“The Soviet Union, which only 40 years ago was a nation of peasants,

today is challenging our America in…the application of science to technology…the path

we chose to pursue may well determine the future not only of western civilization

but freedom and peace for all peoples of the earth.”

This is going to happen to us again – sooner, rather than later – if we don’t elect a person of vision to pick up the pieces of our shattered space program real soon. Fortunately, the election of 1960 provided us with just such a leader – and his opponent, when he later got his own shot at leading humanity into the future, proved to be the very perjurer who would oversee the demise of JFK’s vision.

Ignorance is more costly than taxes.

– Sen. Thaddeus Stephens

Stephens may have been a Republican, but that was back in the days when Republicans were the liberal good guys – Democrat John Kennedy showed he certainly understood the same thing to be true in a speech at Rice University in 1962:

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war. I do not say the we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

Kennedy went on to describe the huge cost of the national effort to first pass, then defeat, the Soviets in the race to space. He was blunt and honest in a way that a supporter of a Gas Tax Holiday could never hope to be:

That [space] budget now stands at $5,400 million a year–a staggering sum, though somewhat less than we pay for cigarettes and cigars every year. Space expenditures will soon rise some more, from 40 cents per person per week to more than 50 cents a week for every man, woman and child in the United Stated, for we have given this program a high national priority–even though I realize that this is in some measure an act of faith and vision, for we do not now know what benefits await us.

The Rooskies continued to play off the momentum of their earlier gains, and racked up an impressive list of “firsts” in the early 60s. The now-defunct USSR lays claim to the first:

- Terrestrial Creature in Space – Laika the dog was launched into orbit aboard Sputnik 2 in November, 1957. She survived longer than mission planners expected, but regardless, no provision was ever made for her live recovery.

- Man in Space – Yuri Gagarin flew Vostok 1 into orbit on April 12, 1961. Alan Sheppard, aboard Mercury 1, became the first American to orbit the Earth three weeks later.

- Woman in Space – Valentina Tereshkova flew aboard Vostok 6 on June 16, 1963. Embarrassingly, the United States did not entrust a space mission to a woman until 20 years (nearly to the day) later, when Sally Ride flew aboard Space Shuttle Challenger on STS-7, launched June 18, 1983. The first African-American to orbit the Earth, incidentally, was Guion “Guy” Bluford, Jr., who launched on August 30, 1983. In 1992, NASA finally saw fit to allow an African-American woman to go to space – Mae Jemison, aboard the Shuttle Endeavor. It wouldn’t be until 1995 that a woman was entrusted with the controls of a NASA spacecraft – when Eileen Collins piloted Discovery.

- Space Walk – Alexei Leonov was upwards of 17 feet away from his Soyuz capsule for 12.5 minutes in 1965.

But the US plugged on, first closing the gap, then moving into the lead under President Johnson. The crowning achievement, of course, came in the year Johnson left office – it was a new president that got to radio the congratulations and receive the world’s acclaim for the program envisioned by Kennedy and doggedly pursued by Johnson. For a split-second on July 20, 1969, though, it didn’t really matter who had funded what, who was enemies with whom, or even which economic system the great superpowers were choosing to impose upon the people of Earth. The reason:

“It’s too bad, but the way American people are, now that they have all this capability, instead of taking advantage of it, they’ll probably just piss it all away.”

– President Lyndon B. Johnson, on ending the Apollo program

It may be a tad crudely put, but Johnson prophesied correctly. In the Grand Old Party tradition of tearing down the good works done by Democratic predecessors, President Nixon slashed funding to the space program, obligating NASA’s planners to make some tough decisions about what they could afford and what they couldn’t. Among the projects scrubbed were Apollo missions 18 through 20, as well as orders for new Saturn V rockets; among the handful of programs that NASA opted to continue were the Space Shuttle and Skylab.

The idea of an orbiting space station goes back at least as far as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), whose famed “Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot remain in the cradle forever” quote helped give rise to the entire genre of science fiction. As early as the 1950s, Werner von Braun was talking about setting up a science station in orbit using the spent parts of rocket boosters – in the end, budgetary constraints that caused NASA to go with a similar plan in order to get the most stripped-down model of a orbiting station that a nation looking for a manned presence in space could finagle.

Skylab was basically the S-IVB second stage of a Saturn IB booster, fitted with a bunch of Apollo equipment (and with more strapped to the outside – more on how this worked out in a minute). The version that went into space was a “dry-workshop” design – no fuel was ever stored in the lab space – as opposed to the “wet-workshop” which had earlier been considered (this one would have involved using the third stage as a fuel tank during launch, then adding equipment after the residual hydrazine had been vented into space). It weighed 78 tons, was about the size of a bus, and sported an IBM System/4Pi TC-1, which is an ancestor of the AP-101 computers used on the Space Shuttle.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Last week, some guy in Minnesota (danger: link goes to Faux News) announced that he recovered the data from one of the computers that had been aboard the Shuttle Columbia when it broke apart over Texas in 2003. That any information was recoverable at all is amazing, but what really blows the space-age mind is the fact that our Space Shuttles are running on a DOS system, which I’m told by nerdy friends is nowadays considered the computer equivalent of a slide rule.

Earth is too small a basket for mankind to keep all its eggs in.

– Robert A. Heinlein

Skylab – the name came from a NASA-sponsored contest – roared off toward space on May 14, 1973, atop a Saturn INT-21 (the 2-stage version of a Saturn V). For 62 seconds, all went well; after that, not so much. The station’s micrometeoroid/sun shield tore off, as did one of its main solar panels. To make matters worse, the crap that was still half-attached to the hull was pinning another of the solar panels in place, which prevented it from deploying and left the station with very little power. Over the course of the next few days, some of NASA’s engineers monkeyed around with the station’s orbit, using thrusters to keep the now-unshielded parts pointed away from the sun, while others worked on a way to make the thing habitable again.

They didn’t have much time to work: if they didn’t come up with a fix quickly, the sun would melt the station’s insulation, which would release poisonous gases and render Skylab completely unusable before any human ever got the chance to float around in it. Though this was officially considered a long shot, ground control nevertheless vented and repressurized the craft four times before they allowed a gas-mask-wearing crew to enter. Of more immediate concern were things like what the 150° temperatures might be doing to the food stored aboard, and how to lower the temperature enough so that it wouldn’t bake the astronauts in a gold-foil oven.

Their solution? A tarp. Oh, sure, it was high-tech and all that, but the concept at work was pretty much the same as the awning on a house. Since it was going to have to be deployed by an astronaut actually going outside, the tarp became known as the SEVA – for “Standup Extravehicular Activity” – sail. In the process of designing and fabricating it, NASA learned that doing rocket science with an audience could be a tad unnerving – and that wasn’t the only problem they faced:

Responsibility for the SEVA sail fell to Caldwell Johnson, chief of the spacecraft design division. He organized a development team and worked in the centrifuge building; for 10 days the group felt like goldfish in a bowl, as public tours to the centrifuge observed their activity from a mezzanine. Seamstresses stitched the orange material, parachute packers folded the sail for proper deployment, and design engineers attended to the various fasteners. Probably the biggest obstacle was getting exact data on Skylab, since some drawings were not current. In one or two instances, the engineers relied on photographs provided by McDonnell Douglas. Johnson faced an additional problem-warding off suggestions from other NASA officials, whose good intentions might have improved the design at the expense of the deadline. In spite of minor delays, the SEVA sail made rapid progress.

Mission SL-2 was launched on May 25, and saw the successful deployment of the tarp SEVA sail. The crew, which consisted of Charles C. Conrad Jr., Paul J. Weitz, and Joseph P. Kerwin, spent a little less than a month in space, splashing down on June 22, 1973. The next crew, Alan L. Bean, Jack R. Lousma, Owen K. Garriott, spent twice as long in orbit – 59 days, during which they continued to patch the station together while conducting extensive medical and scientific experiments. Their crew also included two spiders, named Arabella and Anita, who were brought aloft at the suggestion of a junior high school student in Lexington, Massachusetts (her name was Judith Miles), who wondered if spiders would be able to spin webs in a microgravity environment. They were (pdf), though both spiders ultimately gave their lives in the pursuit of science: they died of thirst while still in space.

Weird Historical Sidenote: NASA’s average employee may be able to calculate pi to a hundred places, but they managed to screw up the numbering of the missions to the ill-fated Skylab station. Originally, the plan was to term the first, unmanned mission SL-1, followed by the manned missions, which would be designated SL-2 through SL-4. Somewhere along the way, somebody got it into his (and it probably was a he) head that the numbering only referred to the manned missions, and documentation started showing up indicating SLM-1 through SLM-3. By the time the administrators made a decision to go with the 2-3-4 option, the uniform patches, etc., had already been created using the 1-2-3 scheme.

For more on Arabella and Anita (including a pic of one or the other of them), check out this pdf

Development of the space station is as inevitable as the rising of the sun; man has already poked his nose into space and he is not likely to pull it back . . . . There can be no thought of finishing, for aiming at the stars-both literally and figuratively-is the work of generations, and no matter how much progress one makes, there is always the thrill of just beginning.

– Werner von Braun, 1952

There’s also the thrill of sticking your nose where it doesn’t belong. SL-3 (Gerald P. Carr, William R. Pogue, and Edward G. Gibson) stayed up for 84 days, during which they ran afoul of both their ground controllers and, eventually, the inner sanctum of the CIA. The first problem was familiar to anyone who’s had a boss that shouts orders over a radio:

…the all-rookie astronaut crew had problems adjusting to the same workload level as their predecessors when activating the workshop. One of their first tasks was to unload and stow within Skylab thousands of items needed for their lengthy mission. The schedule for the activation sequence dictated lengthy work periods with a large variety of tasks to be performed. The crew soon found themselves tired and behind schedule.

As the activation of Skylab progressed, the astronauts complained of being pushed too hard. Ground crews disagreed; they felt that the astronauts were not working long enough or hard enough, and insisted the crew work through their meal times as well as their rest days to catch up.

They finally got sick of it, and dealt with the earthbound slavedrivers in the same way Captain Kirk did: they shut off their radio and declared themselves a 1-day holiday. It was likely the first mutiny on a US spacecraft, and the crew paid the price for it – none of them ever flew a NASA mission again.

That wasn’t the only trouble SL-4’s crew got themselves into. When they splashed down on February 4, 1974, all the pictures they had taken of Earth were turned over to the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) per longstanding agreement – it went back to Gemini days – with the nation’s intelligence community. On the one hand, the analyses were to see if the astronauts were producing any decent spy photos; on the other, it was to make sure they weren’t snapping pictures of things they shouldn’t. This pdf tells the tale, as does the portion of it quoted in Dwayne Day’s 2006 article Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident:

“The issue arises from the fact that the recent Skylab mission inadvertently photographed” the airfield at Groom Lake [a/k/a Area 51]. “There were specific instructions not to do this,” the memo stated, and Groom “was the only location which had such an instruction.” In other words, the CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake, and the astronauts had just taken a picture of it.

The existence of an astronaut’s photo of Area 51 presented the government with a bit of problem, since they were in the habit of denying that there was any such place. As quoted and noted by Day:

The existence of an astronaut’s photo of Area 51 presented the government with a bit of problem, since they were in the habit of denying that there was any such place. As quoted and noted by Day:

“This photo has been going through an interagency reviewing process aimed at a decision on how it should be handled,” the unnamed CIA official wrote. “There is no agreement. DoD elements (USAF, NRO, JCS, ISA) all believe it should be withheld from public release. NASA, and to a large degree State, has taken the position that it should be released-that is, allowed to go into the Sioux National Repository and to let nature take its course.”

Note to younger Kossacks – in those quaint days, government agencies often talked with one another to coordinate responses or develop plans. Weird, hunh?

The final option was the one the government went with – they simply dumped the photo in with thousands of others, and did nothing to attract any sort of attention to it. The stink the picture had caused only became apparent with the declassification of CIA memo about it, and as for Area 51…well, the Air Force finally got past the denial stage in 1999, admitting to existence of the base, but not pausing to take questions about the reverse-engineering of alien technology or the filming of fake Moon landings that were said to occur there.

The 70s cheese factor is strong in this one

– Obi-Wan Kenobi (paraphrased)

In a sense, Skylab was a microcosm of the 1970s as a whole – check out the mission patches if you don’t believe me:

Here we see SL-1 depicted with the standard Apollo-style “gadget hanging nobly in space” design, but the creeping influence of what may be Grateful Dead-type psychedelia is visible in the SL-2 patch, if you squint your eyes and look at it just right. SL-3 had something of sciencey/détente thing going, but by the time of SL-4, that same 70s zeitgeist that would give us way-overengineered, “epic” rock albums was cropping up in descriptions of astronaut patches:

“The symbols in the patch refer to the three major areas of investigation in the mission. The tree represents man’s natural environment and refers to the objective of advancing the study of earth resources. The hydrogen atom, as the basic building block of the universe, represents man’s exploration of the physical world, his application of knowledge, and his development of technology. Since the sun is composed primarily of hydrogen, the hydrogen symbol also refers to the Solar Physics mission objectives. The human silhouette represents mankind and the human capacity to direct technology with a wisdom tempered by his regard for his natural environment. It also relates to the Skylab medical studies of man himself. The rainbow, adopted from the Biblical story of the Flood, symbolizes the promise that is offered to man. It embraces man and extends to the tree and hydrogen atom, emphasizing man’s pivotal role in the conciliation of technology with nature by a humanistic application of our scientific knowledge.”

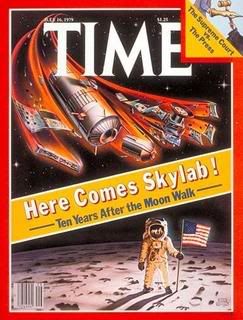

As all but a handful of dead-enders walked away from supporting Nixon in the summer of 1974, so, too was Skylab – with its inoperative and/or marginally-functional gyros, erratic coolant systems, and dying power modules – condemned to abandonment. Before SL-4 left, they flew the station into a new orbit 11 km higher, then turned out the lights on most of Skylab’s critical systems. The plan was to leave the derelict in orbit until the early 80s (NASA’s numbers calculated Skylab’s orbit holding until 1983); the Space Shuttle would then fly a couple of fix-it missions. Little did those Ford-era planners realize that the Shuttle program wasn’t exactly going to break many of Apollo’s construction-related speed records. By 1978, it was clear that Skylab, whose solar-storm-battered orbit was starting to decay, was going to be in deep trouble long before a Shuttle was going to be able to lumber up and fix it.

Significant – and costly – efforts were made through most of 1978 to figure out a way to at least boost Skylab into a higher orbit, but the station was falling faster than “reboost” components were coming on-line. A cost/benefit analysis didn’t exactly play out in Skylab’s favor, either: the program had cost over $2.5 billion, and now efforts to rescue it after 5 years of disuse were approaching $4 million. By December, NASA gave up on salvaging the derelict station, and started preparing to deal with the impact (literally) of having 78 tons of space junk re-enter the Earth’s biosphere. On the 15th, President Carter was told that about the best NASA could hope for was to exert some minimal control over the re-entry profile of what was certain to be a flaming wreck, and that Skylab would likely come down sometime in the summer of 1979.

The Earth was small, light blue, and so touchingly alone, our home that must be defended like a holy relic.

– Aleksei Leonov

Can’t say I disagree in the slightest with the sentiments of the first man to walk in space, and it’s likely that neither would the folks at NASA, but there was precious little they could do to direct Skylab’s re-entry. What they could control was the public voice of the agency regarding the time and place of the coming crash, and this they did with a message discipline that would make George Steponallofus and the rest of the Clintonian spin-doctors of the 1990s proud. This turned out to be a good idea; in late March, the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant nearly melted down, and the resultant confused panic highlighted the need for consistency in governmental agency pronouncements.

Earthlings had recent experience with the prospect of death raining from the heavens – indeed, Skylab had made observations of the Kohoutek: Comet of the Century (a/k/a “Comet Watergate”) as it entered the inner solar system for the first time in 75,000 years. Such a long period, coupled with a name that many mistook for an Egyptian necromancer or something (it was actually the surname of the Czech astronomer who discovered it in 1971), led to speculation that humanity was doomed. In addition to annihilating Earth, Kohoutek was expected to provide a great light show in the form of outgassing; there was significant let-down when neither event came to pass.

That Kohoutek would go do in history as a dud didn’t stop a handful of true nutbags (like the “Children of God” followers of David Berg, who distributed literature and fled to communes in the face of a cataclysm predicted for January, 1974) who were convinced the comet was the harbinger of death, though, and these folks reprised there roles when word starting getting out about Skylab.

As Skylab circled the drain more and more rapidly, some folks took a less-alarmist approach to the prospect of armored school buses falling from the heavens:

As Skylab circled the drain more and more rapidly, some folks took a less-alarmist approach to the prospect of armored school buses falling from the heavens:

In Washington, two computer specialists established a firm called Chicken Little Associates, offering to provide up-to-the-minute estimates of the danger to any specific person, for a fee. With the implication that NASA’s predictions were unreliable, Chicken Little drew publicity-especially abroad. Then, just a month before reentry, a group from the Brookline (Mass.) Psychoenergetics Institute attempted to increase Skylab’s altitude by telekinesis. They staged a “coordinated meditation” session in several eastern states, but produced no effect detectable on NORAD’s radars.

Office pools sprung up, “Skylab parties” were arranged, somebody started manufacturing “Skylab survival kits” (complete with plastic helmet), and at least one pregnant woman offered to name her child after the space station in exchange for a little bit of that NASA funding. In early July, NASA was able to narrow the window to a few days; by the 9th, flight controllers were fairly confident in predicting re-entry on the 11th. As the successive orbits got lower and lower, the window was reduced to a few hours, and the site of the impact was (mercifully/luckily/skillfully) predicted to be in an uninhabited section of the central Indian Ocean.

Office pools sprung up, “Skylab parties” were arranged, somebody started manufacturing “Skylab survival kits” (complete with plastic helmet), and at least one pregnant woman offered to name her child after the space station in exchange for a little bit of that NASA funding. In early July, NASA was able to narrow the window to a few days; by the 9th, flight controllers were fairly confident in predicting re-entry on the 11th. As the successive orbits got lower and lower, the window was reduced to a few hours, and the site of the impact was (mercifully/luckily/skillfully) predicted to be in an uninhabited section of the central Indian Ocean.

In the end, the predictions were just about right – estimated time of impact was 1237 EDT, and the reentry footprint did begin in the Indian Ocean – but Skylab’s famed fragility, which had been counted on to start the craft’s breakup over the eastern US, failed to materialize. Skylab thus held together longer than expected, which caused it to fling pieces of itself further east than anticipated. The final footprint was across a strip about 4° wide, beginning at about 48° S 87° E and ending at about 12° S 144° E, made up of open ocean and the west end of continental Australia. At NASA, there was little left to do but pack up the Skylab shop and leave orbiting space stations to the Soviets.

That’s not to say, however, that the rain of fiery debris didn’t have its benefits:

One Australian, in fact, profited handsomely from the overshoot. A San Francisco newspaper had offered $10 000 for the first authenticated piece of Skylab brought to its office within 48 hours of reentry, and on the morning of 13 July a claimant appeared. Stan Thornton, a 17-year–old beer-truck driver from the small coastal community of Esperance, had found some charred objects in his back yard, bagged them up, and caught the first plane for California. He arrived without passport and with only a shaving kit for luggage, but the pieces were identified as remains of plastic or wood insulation from Skylab, and Thornton got his prize.

Even the town of Esperance tried to engage in a little (thus far unsuccessful) profit-taking – read Satellites Falling: Skylab Costs America a Litter Fee in Australia to find out how the US government stiffed the tiny hamlet of the $400 ticket it was issued. Coincidentally (or not? – this guy certainly wouldn’t think so), the Miss Universe pageant was being held in nearby Perth a few days later; the Aussies put a large chunk of debris on display on the stage.

And the Skylab legacy? Well, NASA’s official history tries to look at it through a rose-colored, gold-shielded face plate:

Experimenters learned much from the Skylab program. So did crews and flight planners: what they learned was something about the infinite variability of man. The resourceful “can-do” first crew was succeeded by a hard-driving group of overachievers and in turn by the methodical, sometimes stubborn third crew. No one could reasonably fault the performance of any of these crews, but once more it was impressed on everyone in the program that astronauts are not interchangeable modules.

Historiorant:

There’s plenty more to say here, but this is already getting rather long (in addition to being a day late), so I’ll have to table the part about the International Space Station and the two Shuttle disasters for a later space-related diary.

That upcoming diary will be my third on space-related matters; the first was The Nika Riot of December 30, 2006, in which I advocated for the construction of a Space Elevator. I mention this because I don’t want to be misinterpreted – I fully support NASA’s mission, and desire little more than to see the US re-assert our visionary leadership in the exploration of space. I feel strongly that every time we send a launch into space, we as a species learn something critical about the next step in humanity’s eventual destiny – as Gene Roddenberry said, Why our space program? Why, indeed, did we trouble to look past the next mountain? Our prime obligation to ourselves is to make the unknown known. We are on a journey to keep an appointment with whatever we are. As an historioranter and a taxpayer, it’s my job to keep an eye on (and to celebrate or to mock, as appropriate) these programs; if my tone is occasionally snarling, it’s because I believe we can, should, and need to do better than we have in the past.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

And if you’re in the vicinity of Columbus, Ohio, from June 25-29, make sure to drop by WILDSIDE Gaming System tables at the Origins Game Fair – check out the Wildside Gaming Events link for our Kossack meet & greet.

14 comments

Skip to comment form

i’m heading to bed…will reread with coffee in AM!

(-.-)g’nite! Zzz..zz

surely this needs one?

Star Womb

On a cosmic scale

the scale of star stuff

we are all

so insignificant

minor players

on a minor stage

Just dust in the wind

evaporating in a relative

wink of an eye

or so I have been told

One can also

hold the view

that the vastness

of spacetime

gives primacy

to that stage

and to this life

while it occurs

Earth is my universe

until I can leave it

I am immortal

until I die

–Robyn Elaine Serven

–December 14, 2005

Thank you for a wonderfully informative diary.

Now, I only have to go back & check out all the links.

I love the “human” aspect of how you wrote this essay.

Some days, I also, turn the radio off.

is located in Balldonia, Australia (Western Territory) at the Nullarbor Museum & RV Park.

Here is a picture:

Nullarbor is Latin for No trees – a perfect name for this unique ecological region.

A vast, deserted plain of brush and sand dunes continually scrubbed raw by the grey winds of the Southern Ocean.

A place where the kangaroos outnumber the humans by at least 100 to 1. In fact, per capita, you may never find a more desolate stretch of highway.

and then you see Skylab…

I have a personal connection to Skylab. Further skimming here, it’s specifically to the outside of Skylab and the more- on- that- in- a- minute stuff.

Speaking of weird space program karma, in those days I was crewing with a friend and a NASA manned space engineer on a small cruiser/racer sailboat of the brand “Columbia Challenger.”

Honestly, it wasn’t named “Donner Pass.”

I dimly recall that the shuttle that would be named “Columbia” was supposed to boost Skylab and prevent entry. But it wasn’t ready in time, I think because of problems with its heat shield tiles, and Skylab sagged till it burned up.

Columbia, tiles….

I particularly love this subject. I worked on the Hubble Space Telescope project and it forever opened my eyes to the staggering wonders of the universe.

I’ve heard people object to the money we have spent on space exploration but it is truly a drop in the bucket compared to what we spend on bombs to drop on other peoples’ babies. Plus it advances science, increases our knowledge, stokes our imaginations, expands our sense of wonder and is in virtually every way benign.

There are more important things like feeding the hungry, caring for those in need, etcetera – but the space program is no impediment. We can meet our serious responsibilities and fully fund science across the board too…once we quit pouring our treasure down the black hole of unnecessary war and stop the thievery in our government and corporations.