(10 am. Bumped – promoted by ek hornbeck)

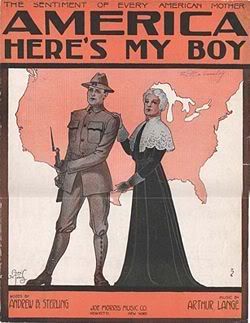

From the plebian soldier’s point of view, the social contract regarding wartime service isn’t all that hard to comprehend. Every generation or so, your country goes to war, with the tacit understanding that the government will: only compel you to bear arms for a limited time; compensate you in some way for your time and effort; and tend to any long-tem injuries sustained while fighting for the government’s causes. So it is that every generation or so, a group of veterans returns to the United States in full belief that the government which sent them into battle will care for their wounds and honor their service – and in nearly every case, find their naïve hopeful trust violated in the most unconscionable, unpatriotic ways.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight your resident historiorantologist will start looking at how that government treated some of the veterans of a war four generations removed from the Iraq Occupation. Along the way, we’ll take a look at a war message that doesn’t seem to have lost much relevance – or many talking points – over the past 91 years.

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go,

Over four-and-one-half million men served in the American armed forces in 1917 and 1918, and while only about half of them ever made it to Tipperary or beyond, a full 1.1 million wound up in combat. 116,516 never came home (source) – a number larger than the entire U.S. military at the time of the declaration of war. In all, there were 323,018 US casualties – the number does not include MIAs – but given that this was the war that introduced the civilized world to chemical WMD, strategic bombing, and the creeping artillery barrage, the numbers are probably low. The Great War, after all, gave us the term “shell shock,” which is now recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder, and it exposed the relatively sheltered youth of a predominantly-rural America to horrendous scenes like this gas attack:

or the mournful, backbreaking process of burying their fallen comrades:

The origins of the Great War are the stuff of other diaries, as are thousands of its other yet-unmoonbatified aspects; what’s important for our purposes tonight is the way returning veterans were sent, and welcomed home, by the citizenry and the government that had dispatched them to the no-man’s lands of Flanders and France.

Though the vast bulk of the military had seen no combat (and even among those who had, time before the enemy usually amounted to twelve months or less), the soldiers were proud of their contributions. Their President had told them to go to Europe and fight the Hun, to “make the world safe for democracy,” and they had responded. That their enemy was exhausted by three years of meatgrinding trench warfare didn’t factor into the equation all that much: Woodrow Wilson had told them that the Germans were waging

Though the vast bulk of the military had seen no combat (and even among those who had, time before the enemy usually amounted to twelve months or less), the soldiers were proud of their contributions. Their President had told them to go to Europe and fight the Hun, to “make the world safe for democracy,” and they had responded. That their enemy was exhausted by three years of meatgrinding trench warfare didn’t factor into the equation all that much: Woodrow Wilson had told them that the Germans were waging

…a war against all nations. American ships have been sunk, American lives taken, in ways which it has stirred us very deeply to learn of, but the ships and people of other neutral and friendly nations have been sunk and overwhelmed in the waters in the same way. There has been no discrimination. The challenge is to all mankind. Each nation must decide for itself how it will meet it. The choice we make for ourselves must be made with a moderation of counsel and a temperateness of judgment befitting our character and our motives as a nation. We must put excited feeling away. Our motive will not be revenge or the victorious assertion of the physical might of the nation, but only the vindication of right, of human right, of which we are only a single champion.

Wilson’s War Message to Congress, April 2, 1917

And such challenges must be risen to. Wilson let it be known that it would be no cakewalk, but that the United States was obligated to take a stand in what was, in modern parlance, the defining struggle of the era:

There are, it may be, many months of fiery trial and sacrifice ahead of us. It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts — for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.

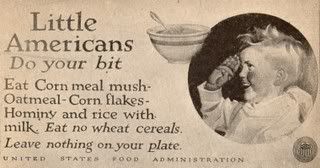

Turns out there may have been some deeper, more money-related reasons behind the U.S. getting involved in the war (a little more on that in a bit), but for the bulk of the American citizenry – who for years had heard tales of atrocities in Belgium, Lusitanias being sunk, and finally, the clear and present danger of a military alliance between Germany and Mexico – Wilson’s stirring speech sounded like the right sorts of reasons for a nation to go to war.

Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag,

And smile, smile, smile.

Wilsonian preaching didn’t mean that America’s meager 100,000-or-so man army enjoyed a huge surge in enlistment, depite the president’s call for volunteers: three weeks after the declaration of war, only 32,000 men had signed up. So it was that Wilson, who had won reelection the year before on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of the War,” began calling for a draft – and in the process taking Obama-on-FISA-type hits from his own Democratic Party, who said he was destroying democracy at home in his efforts to make the world safe for it abroad. The Selective Service Act of 1917 was passed over noninterventionist opposition on May 18, 1917.

By the end of the war, 24 million men between the ages of 21 and 30 (later expanded to ages 18-45) were registered; just over 2.8 million were actually inducted. The Selective Service Act of 1917 was not the first time Americans had been drafted into the armed services, but it did try to close some of the more glaring loopholes in its Civil War-era predecessor. Chief among these was an outright prohibition on being able to buy one’s way out of service, be it with cash or by sending a surrogate.

Around 13% of the draftees were black, which led to a peculiar dichotomy that was seized upon by a German propaganda campaign: here were American soldiers (though serving in a racially segregated military) who lacked the very rights at home they were ostensibly in Europe to protect. For their part, many blacks thought that a grateful nation would, upon their return, reward them with the rights they’d been so long denied. W.E.B. DuBois summed up this appeal to the Greater Good:

Around 13% of the draftees were black, which led to a peculiar dichotomy that was seized upon by a German propaganda campaign: here were American soldiers (though serving in a racially segregated military) who lacked the very rights at home they were ostensibly in Europe to protect. For their part, many blacks thought that a grateful nation would, upon their return, reward them with the rights they’d been so long denied. W.E.B. DuBois summed up this appeal to the Greater Good:

“Let us, while the war lasts, forget our special grievances and close ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens … fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make it gladly and willingly.”

Things didn’t work out quite the way DuBois might’ve been hoping for: men who had won high military honors (several members of the 396th Infantry – the “Harlem Hellfighters” – were awarded the Croix de Guerre) fighting on behalf of freedom and liberty found themselves subjected to harassment up to and including lynching when they returned and sought to reenter the American workforce. In a sense, their plight was emblematic of the returning victorious forces as a whole: there were plenty of parades and lots of back-slapping initially, but the rapid demobilization of millions of soldiers at the war’s end – coupled with a massive retooling of factories and a devastating Influenza Pandemic – led to a coupled of years of a miserable economy before the 1920s really got to roaring.

Things didn’t work out quite the way DuBois might’ve been hoping for: men who had won high military honors (several members of the 396th Infantry – the “Harlem Hellfighters” – were awarded the Croix de Guerre) fighting on behalf of freedom and liberty found themselves subjected to harassment up to and including lynching when they returned and sought to reenter the American workforce. In a sense, their plight was emblematic of the returning victorious forces as a whole: there were plenty of parades and lots of back-slapping initially, but the rapid demobilization of millions of soldiers at the war’s end – coupled with a massive retooling of factories and a devastating Influenza Pandemic – led to a coupled of years of a miserable economy before the 1920s really got to roaring.

That little speed bump on the road to recovery, plus inflation that had occurred over the course of the war, meant that the $1 per day that soldiers had been paid was no longer worth what a pre-war dollar had been – and they started agitating for a little “bonus” that would help even things out. President Harding (R-naturally) vetoed a bonus measure – fascinating pdf of a New York Times article from September, 1922, here – but his successor, Calvin Coolidge (R-no further comment), was rebuffed when his veto of a bonus bill was overridden in 1924 and the Adjusted Service Certificate Act became law.

Under its terms, vets would receive $1 for everyday they’d served stateside to a max of $500; they’d get $1.25 for every day overseas, up to $625. Claims of under $50 were paid out immediately; the other 3,662,374 veterans got certificates payable upon the maturity of the certificate – in 1945. Since this was back in the days when Congress actually paid for most of the stuff it enacted, the Adjusted Service Certificate Act set up a trust fund and earmarked 20 installment payments of $112 million each. Taken together with the interest that would accumulate along with the mounting payments, the fund was so solvent that vets were even allowed to take out loans against 22.5% of face value.

By 1931, future prospects weren’t quite as rosy as they’d appeared back in the heady days of 1924; the vets were starting to ask for the bonus to be paid out immediately. Over President Hoover’s (R-what else?) objections, the loan amount was raised to 50% of face value, but as the summer of the 1932 election year approached, a lot of vets were saying that it just wasn’t enough. They began making preparations to travel to the nation’s capital to petition their government and redress their grievances – little aware that getting mustard-gassed by the Kaiser’s troops at Chateau Thierry was no guarantee that MacArthur’s soldiers wouldn’t tear-gas a vet on the streets of Washington

Historiorant:

Sorry about the long absence – life’s been interfering with blogging, I’m afraid. Fwiw, I did try to post an artsy-type rewrite of White Man’s Burden at DKos last week, but I couldn’t get it through the HTML Shredder without it…well, shredding. It came out okay at the recently-reopened Never In Our Names – please check it (and the site!) out by clicking the links.

Sorry, too, for the abrupt ending tonight – I think this is the shortest “History for Kossacks” I’ve done since my earliest days as a n00b. The fact is, I felt a distinct need to post one, and if that means I’m going to have to serve up a Part II to cover the rest of the story, then I guess that’s how it’s got to be. Alas! Alas!

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

And my apologies for a long dearth of postings – real life has interposed itself in dozens of inconvenient ways in the past couple of months, and I’m afraid I’ve become more of a sporadic, as opposed to unitary, moonbat than I’m wanting be. This one’s posted here tonight ’cause the second one – The Bonus Expeditionary Force – will be up tomorrow night. With any luck, there won’t be any more hiatusus…or would it be “hiati?”

You’re back.

Can I give up Sundays now and concentrate on something else?

Please?

on a du-aye-alogue moonekblog here. So please forgive me. I just want to express my appreciation for this diary!