It must have had a dreamlike quality to it: a summer’s day in Washington, the tanks and troops on the street accompanied by officers like George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower, led by none other than General Douglas MacArthur. America’s Caesar was wearing a full salad bowl of ribbons and medals, magnificent astride a great horse; to the impoverished veterans he was riding to meet, he must have looked like a mighty warrior of a bygone era. Then, to their horror, the Chief of Staff of the US Army ordered his infantry to fix bayonets, his cavalry to draw sabers, and his tanks to move forward.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, we’re tonight’s historiorant finds Depression-hit vets of the First World War encamped in a Hooverville in Washington during the summer of 1932. I’m not saying it contains lessons to be learned about the interrelationships of Republican presidents, veterans, economic depression, and violent authoritarianism, but as St. Colbert once said, “I can’t help it if the facts have a liberal bias.”

In last week’s episode – thanks for the warm welcome back after an unintentionally-long hiatus, btw – we saw how the American Expeditionary Force was assembled, deployed, and welcomed home. We also saw how those vets were promised upwards of $625 as a “bonus” for their service by the Adjusted Service Certificate Act of 1924 – but with a few catches.

As I historioranted at the end of the last session: under its terms, vets would receive $1 for everyday they’d served stateside to a max of $500; they’d get $1.25 for every day overseas, up to $625. Claims of under $50 were paid out immediately; the other 3,662,374 veterans got certificates payable upon the maturity of the certificate – in 1945. Since this was back in the days when Congress actually paid for most of the stuff it enacted, the Adjusted Service Certificate Act set up a trust fund and earmarked 20 installment payments of $112 million each. Taken together with the interest that would accumulate along with the mounting payments, the fund was so solvent that vets were even allowed to take out loans against 22.5% of face value.

By 1931, future prospects weren’t quite as rosy as they’d appeared back in the heady days of 1924; the vets were starting to ask for the bonus to be paid out immediately. Over President Hoover’s (R-what else?) objections, the loan amount was raised to 50% of face value, but as the summer of the 1932 election year approached, a lot of vets were saying that it just wasn’t enough. They began making preparations to travel to the nation’s capital to petition their government and redress their grievances

The First “Fighting Dem”

Texas congressman John Wright Patman (D-in the south, they pretty much all were) was a Great War vet himself – joined as a private, mustered out as a machine gun officer – and in 1932, he decided to try to both help his fellow ex-doughboys and take a jab at President Hoover at the same time. He was probably assuming that his security in the TX-01 seat wouldn’t be in much danger; if so, history bore him out, as he held it continuously from 1929 until his death in office in 1976.

Patman was an outspoken critic of Hoover’s policies, and was to become an ardent New Dealer once the Republicans were shunted out of office and the adults got a shot at fixing the mess they’d created in the Roaring 20s. In 1932, he advanced a bill that would provided relief – today we’d call it an “economic stimulus package” – by going ahead and redeeming the veteran’s certificates at full value 13 years early. Since a lot of vets had been out of work for nearly as long as the chickens of laissez-faire economics had been home roosting, the certificates were the one asset they had left to their names: they’d already had their savings wiped out by a mismanaged banking system, sold everything they owned, and were on the front lines of the Depression in the same way as they’d been on the front lines in France.

The veterans loved Patman’s bill, and one guy in particular, Walter Waters, felt that the cause would be strengthened if a few thousand vets went to Washington to publicly support it. Accordingly, the 34-year-old ex-sergeant (and unemployed cannery worker) set off from Oregon in mid-May, with about 300 fellow vets. They traveled by commandeered freight cars (significantly, Hoover refused to intervene in a 3-day standoff between Bonus Marchers and B&O Railroad in St. Louis), and along the way, Waters became their leader; it was he who settled a divisive early fight by having the men fall into ranks in military order. Over the course of the two-week trip, the Bonus Expeditionary Force gathered a tsunami of supporters and press attention as they neared the nation’s capital:

The veterans loved Patman’s bill, and one guy in particular, Walter Waters, felt that the cause would be strengthened if a few thousand vets went to Washington to publicly support it. Accordingly, the 34-year-old ex-sergeant (and unemployed cannery worker) set off from Oregon in mid-May, with about 300 fellow vets. They traveled by commandeered freight cars (significantly, Hoover refused to intervene in a 3-day standoff between Bonus Marchers and B&O Railroad in St. Louis), and along the way, Waters became their leader; it was he who settled a divisive early fight by having the men fall into ranks in military order. Over the course of the two-week trip, the Bonus Expeditionary Force gathered a tsunami of supporters and press attention as they neared the nation’s capital:

Irving Bernstein wrote in “The Lean Years” that many marchers said they came to Washington because there was no reason to stay home.

“A Pole from Chicago, at one time with the 39th Division . . . slept in flophouses, usually with other veterans. One day they got to talking about the bonus and, ‘the next thing we knew we were on our way.’ ”

***

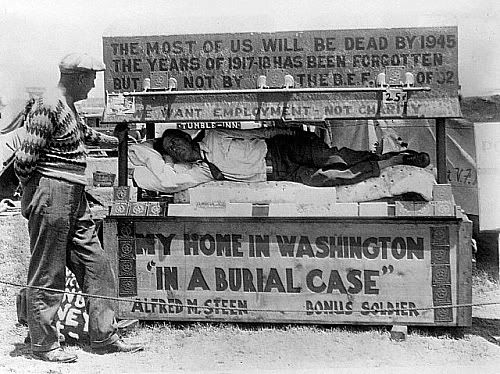

Washington Star reporter Thomas R. Henry wrote that they were “a fair cross section” of America, with “truck drivers and blacksmiths, steel workers and coal miners, stenographers and common laborers. They are black and white. Some talk fluently of their woes. Some can hardly muster enough English to tell where they came from and why.”

The “dusty, weary, melancholy” men were in a struggle “which is too severe for them,” Henry wrote. “They have come to the point where they recognize the futility of fighting adverse fate any longer. . . . The bonus march may as well be described as a flight from reality – a flight from hunger, from the cries of starving children, from the humiliation of accepting money from worn, querulous women, from the harsh rebuffs of prospective employers.”

By the beginning of June, Waters was claiming 80,000 men, women, and children had followed him to Washington; police estimates put the number of what was now being called the “Bonus Army” at around a quarter of Waters’ figure. Regardless of whose guesses were correct, however, what was clear to even the most casual of viewers was that a motley band of economic refugees with a backstory evoking compassion and sympathy had encamped on the doorstep of the President, who displayed neither of those qualities.

By the beginning of June, Waters was claiming 80,000 men, women, and children had followed him to Washington; police estimates put the number of what was now being called the “Bonus Army” at around a quarter of Waters’ figure. Regardless of whose guesses were correct, however, what was clear to even the most casual of viewers was that a motley band of economic refugees with a backstory evoking compassion and sympathy had encamped on the doorstep of the President, who displayed neither of those qualities.

Welcome to Hooverville

Herbert Hoover was plumbing the same depths of popularity as George W. Bush – if nothing else, the Congressional elections of 1930, in which the Dems gained 52 seats (and an eventual majority, after a weird mass extinction event among Republican representatives-elect) in the House and 8 in the Senate, showed that his stances on the Smoot-Hawley tariff, Prohibition, and farm policy (link is to a highly libertarian interpretation) were not exactly winning over the public. By 1932, after months of insisting that the worst was over and that prosperity was “just around the corner,” Hoover was now openly mocked: a newspaper covering a homeless guy on a bench was a “Hoover blanket,” the rabbits raised for food in backyard hutches were “Hoover hogs.”

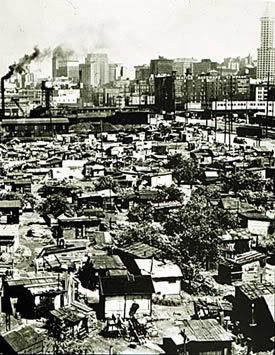

The most famous application of Hoover’s name was to the shantytowns that sprang up on the outskirts of large cities. Constructed of corrugated tin, cardboard, scraps of lumber, and other detritus, Hoovervilles were occupied by families which were jobless and/or whose homes had been foreclosed, and they resembled in every way the horrific conditions we now see in comfortably far-off places like Rio, Sao Paolo, or Lagos: there was no sanitation, spotty (at best) law enforcement, and no provision for even basic governmental services. Here’s one in Seattle – you might recognize the vantage point from the opening credits of Gray’s Anatomy:

As far as Hoover was concerned, the veterans were the city’s problem, and so it fell to Pelham D. Glassford, Washington’s new-on-the-job Chief of Police, to deal with them. Glassford himself was a bona-fide war hero, and he exhibited a great deal of sympathy for the protestors. Amid a swirl of behind-the-scenes politicking, he arranged for the first arrivals to be provided with a hot meal and provided them an unoccupied storefront for their quarters; later, he would secure for their use four federal buildings along Pennsylvania Avenue condemned for demolition as of October of that year, while directing the ever-growing overflow of people to the flood plain along the Anacostia River, southeast of Capitol Hill. Glassford made these arrangements even as he sought to stifle the tide of protestors coming into the city by appealing to governors and veteran’s organizations, and when that failed, by making a personal appeal in Congress to get the Patman bill voted on as quickly as possible.

Falling in on the side of the vets were some heavy-hitting names, like Smedley Darlington Butler. Don’t laugh – this guy was a badass among badasses, one of very few men to be awarded the Medal of Honor twice, and is one of only twenty Marines in the history of the Corps to win the USMC Brevet Medal. He’d served and fought everywhere, and his service record was so sterling that only a scumbag chickenhawk of the Michelle Malkin ilk (these existed, but were much rarer back in those days) would dare to impugn his opinion on matters related to the military – even when he spoke of behalf of the Bonus Marchers or later published a tell-all book entitled War is a Racket.

Weird Historical Sidenote: The thing’s such a rollicking screed, I can’t help but include a couple of excerpts from Smedley Butler’s highly readable rant:

“I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.”

“One very versatile patriot sold Uncle Sam twelve dozen 48-inch wrenches. Oh, they were very nice wrenches. The only trouble was that there was only one nut ever made that was large enough for these wrenches. That is the one that holds the turbines at Niagara Falls. Well, after Uncle Sam had bought them and the manufacturer had pocketed the profit, the wrenches were put on freight cars and shunted all around the United States in an effort to find a use for them. When the Armistice was signed it was indeed a sad blow to the wrench manufacturer. He was just about to make some nuts to fit the wrenches. Then he planned to sell these, too, to your Uncle Sam.”

Meanwhile, the vets kept pouring in, erecting Hoovervilles at four major sites around town, including the large one at Anacostia Flats and one on the National Mall, within sight of the Capitol itself. Waters supervised the construction, laying out the Hoovervilles in precise military order and organizing everything from the laying out of avenues to the assembly of a 300-person volunteer Military Police force. Meanwhile, Glassford arranged for donations from local merchants, people took marchers into their homes, and D.C.’s medical and dental societies set up a 50-bed hospital – but that’s not to say things weren’t getting tense as Congress prepared to vote on Wright Patman’s measure.

How Dare You Be Pathetic in my Alabaster City?

Water’s communities were well-organized – the latrines were sanitary, the troops held formations every day – and morale was high. Before the voting started, Waters said,

“We’re here for the duration and we’re not going to starve. We’re going to keep ourselves a simon-pure veteran’s organization. If the Bonus is paid it will relieve to a large extent the deplorable economic condition.”

Many saw themselves as part of a righteous crusade, an honest petitioning of their government for a redress of grievances; the aforementioned MPs, for example, were more about keeping a group of around 200 die-hard communists from infiltrating the camp and hijacking the protest than crime control among the families in the shanties. Volunteers staffed registration booths, where newcomers had to prove their veteran status (and honorable discharge) to be admitted.

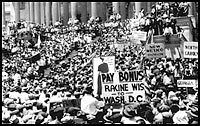

On June 15th, the House passed the Patman bill by a narrow margin, basically along party lines. The majority was not nearly veto-proof, but the Bonus Marchers counted it a great victory – they prayed against hope that there was enough momentum for the bill to pass in the Senate (which had a one-vote Republican majority among the 96 senators), which would then force Hoover to veto the will of Congress, not to mention that of the noble, rag-clad army arrayed across the street from his house. On June 17, the night of the vote in the Senate, upwards of 10,000 Bonusers waited on the steps of their nation’s Capitol to hear the results – only to reel when Walter Waters appeared and announced that the decision hadn’t even been close: 62 troop-haters versus 16 patriots.

On June 15th, the House passed the Patman bill by a narrow margin, basically along party lines. The majority was not nearly veto-proof, but the Bonus Marchers counted it a great victory – they prayed against hope that there was enough momentum for the bill to pass in the Senate (which had a one-vote Republican majority among the 96 senators), which would then force Hoover to veto the will of Congress, not to mention that of the noble, rag-clad army arrayed across the street from his house. On June 17, the night of the vote in the Senate, upwards of 10,000 Bonusers waited on the steps of their nation’s Capitol to hear the results – only to reel when Walter Waters appeared and announced that the decision hadn’t even been close: 62 troop-haters versus 16 patriots.

To lend just a bit more poignancy to the moment, the Bonusers sang “America, the Beautiful,” then formed ranks before marching with dignity back to their hovels. From that point until Congress’ adjournment on July 17, the veterans maintained a silent “Death March” in front of the Capitol.

Like the 4th Amendment after the FISA capitulation, the dream of the Bonus was dead with the failure of the Patman bill. Hoover looked upon this as an opportunity to rid the city of its vermin, and generously offered to buy train tickets home for any Bonuser who wanted to leave – not out of the goodness of his heart or from his own wallet, mind you; the cost of the ticket was to be deducted from the veteran’s final payout. A determined few thousand elected to remain, mostly because they had no place better to go, but the sweltering summer air and the fetid politics of Washington began sapping at the BEF’s strength. The American Communist Party sent in an agent provocateur named John Pace to rile things up, which meant that Waters spent most of July denouncing the Reds who were trying to jump on the bandwagon he’d built. “Eyes front, not left!” became the order of the day.

Glassford, too, tried to maintain a sense of balance. He was also forced to deal with racism in the ranks, especially as boredom grew long and tempers short – upon pulling apart two struggling vets, he is said to have admonished them, “We’re all veterans together and there’ll be no fighting among veterans!” Glassford purchased nearly a thousand dollars’ worth of supplies for the veterans out of his own money, and even came to the aid of the commie Pace, when he told a crowd that

Pace has as much right to speak here as anyone. Any of you who disagree with him and don’t want to listen, go to some other part of the camp and play baseball.

The camp’s newspaper, the B.E.F. News, began agitating for more direct action, as it was becoming apparent that Congress was going to adjourn and go home with near-complete indifference to the plight of the veterans. The number of guards at the White House increased significantly in response, troops were quietly brought in and stationed nearby, and Hoover even dodged the traditional visit to the Capitol for the adjournment ceremonies for fear of running into an angry mob. By July 26, Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley was expressing his displeasure at how peaceful and law-abiding the protesters were – and how it might take nothing less than “an incident” to justify a move toward martial law and clearing the city of the medal-wearing riffraff once and for all.

Hurley’s justification came two days later, when the city commissioners announced that the federal buildings which housed the veterans had had their demolition schedules moved up by a couple of months. They commanded Glassford to conduct the evictions, but it didn’t go well: at the first building the cops approached, the communists, whose leader had been arrested a couple of days earlier, charged the police lines with bricks in hand. Two hours later, as the police entered the second building, one of the officers’ feet slipped between two planks on a stair, and as he fell, he fired multiple shots into a group of veterans. By the time Glassford re-imposed order, two men had been fatally shot by the police, and several more lay wounded.

Hoover’s response to this “provocation” was a swift as it was authoritarian.

Historiorant: Like any story of this type, the details of the riots on the morning of July 28 vary with the source. Another account of the Battle at the Area that Was to Become the Federal Triangle has a police officer receiving a fractured skull from a thrown brick, and Chief Glassford’s gold badge being torn from his breast by an angry protester.

“You will have United States troops proceed immediately to the scene of the disorder. Surround the affected area and clear it without delay. Any women and children should be accorded every consideration and kindness. Use all humanity consistent with the execution of this order.” — memo from Hurley to MacArthur, dated 2:55 p.m. July 28, 1932

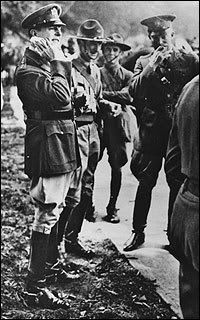

He probably shouldn’t have been on the street in the first place – his aide, Major Dwight Eisenhower, advised against it – but there was no way the technically of having a staff job was going to keep Douglas A. MacArthur from marching toward the drums (that’s Ike sucking a butt in the photo, the second guy from MacArthur’s left). By 4:45 PM, MacArthur had readied his force: four companies of infantry, four troops of cavalry, a mounted machine gun squadron, and six Renault tanks assembled on Pennsylvania Avenue, near 12th Street. It was quite a sight, as noted in this 1999 Washington Post article:

He probably shouldn’t have been on the street in the first place – his aide, Major Dwight Eisenhower, advised against it – but there was no way the technically of having a staff job was going to keep Douglas A. MacArthur from marching toward the drums (that’s Ike sucking a butt in the photo, the second guy from MacArthur’s left). By 4:45 PM, MacArthur had readied his force: four companies of infantry, four troops of cavalry, a mounted machine gun squadron, and six Renault tanks assembled on Pennsylvania Avenue, near 12th Street. It was quite a sight, as noted in this 1999 Washington Post article:

Constance McLaughlin Green, in her book, “Washington, a History of the Capital, 1800-1955,” gave this account: “In the lead rode General Douglas MacArthur, his medals shining on his immaculate uniform, his boot gleaming, his horse perfectly groomed. It was a magnificent sight. The bedraggled men sitting on the curb and the crowd gathered nearby watched with fascination.”

So did the hundreds of civil service workers who spilled out onto the streets to witness what many thought might be a final honor for the Bonus Expeditionary Force – perhaps a parade to escort them out of the city – and the vets began cheering. The cheers turned to cries of “Shame! Shame!” when the cavalry, under the command of George S. Patton, charged the veterans with sabers unsheathed. The troopers had been instructed by Patton prior to the commencement of hostilities:

“If you must fire do a good job-a few casualties become martyrs, a large number an object lesson. …When a mob starts to move keep it on the run. …Use a bayonet to encourage its retreat. If they are running, a few good wounds in the buttocks will encourage them. If they resist, they must be killed.”

— via dissidentvoice.org

The infantry paused to put on their gas masks, then fired adamsite “candles” into the crowd before marching into what was left of their enemy’s lines. The veterans were quickly routed out of the downtown area, and MacArthur pursued them to the Anacostia bridge. A ragged vet appeared on the other side, waving a white flag of truce, and convinced the head of the U.S. Army to give them time to evacuate the women and children; Big Mac replied that he would halt his advance for one hour. During this time, Hoover sent at least two notes demanding that MacArthur stop where he was; the Great General blew them off. Against explicit orders, he sent his tear-gas-firing troops across the Anacostia bridge and into the veteran’s Hooverville.

The fighting went on most of the night; in the bleak dawn that followed, the entire camp had burned to the ground, two veterans lay dead, the wife of a veteran had miscarried, and another baby lay dead from adamsite gas inhalation. Hundreds were wounded; thousands if one considers what being viciously attacked by the very army for which one had once fought would do to an ex-soldier’s psyche. A 7-year-old named Eugene King was bayoneted in the leg when he tried to push past a soldier to rescue his pet rabbit, and Joe Angelo, who had won a Distinguished Service Cross (our nation’s second highest award for valor) in the act of saving a young Lieutenant Patton from certain death at the hands of the Kaiser, now found that his old commanding officer refused to so much as recognize him.

Let the Ass-Covering Commence

Many words were written and spoken about the fate of the Bonus Expeditionary Force; it was a favorite human interest story for the rest of the Depression, until the need for a new generation of patriotic Americans to serve in an even greater war arose. Eisenhower was typically mournful about his role as Right Hand of the Executioner:

“the whole scene was pitiful. The veterans were ragged, ill-fed, and felt themselves badly abused. To suddenly see the whole encampment going up in flames just added to the pity.”

…while Macarthur, ever the spotlight-bathing opportunist, unleashed his massive ego upon a press conference (back in those days, it was very uncommon for a military officer to address the media directly) in which he explained that he was only trying to protect the President from the commies:

‘(The mob) was animated by the essence of revolution. They had come to the conclusion, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that they were about to take over in some arbitrary way either the direct control of the government or else to control it by indirect methods. It is my opinion that had the president let it go on another week the institutions of our government would have been very severely threatened.’

If Herbert Hoover had suffered under a poor public perception before, it was measurably worse after the bloody crackdown. Thrice-broken vets staggered home in a daze, replacing those old, forgotten soldiers of the Spanish-American and Civil Wars who had been their predecessors in starving on streetcorners after sacrificing a youth to their nation. He was unable to shake the images in the runup to the elections that November, but he was unable to resist that old Republican chestnut of blaming the Dems for his own self-caused ills:

‘This whole Democratic performance was far below the level of any previous campaign in modern times. My defeat would no doubt have taken place anyway. But it might have taken place without such defilement of American life.’

Hoover, of course, got trounced in an almost-embarrassing landslide, but it turned out the FDR had the same aversion as Hoover to paying direct benefits to a single special-interest group, no matter how worthy that group might be. In 1933, he vetoed a bill that would’ve paid the bonus in full, but he did respond a little better than Hoover had to the much-smaller gathering of veterans that spring: he first signed an executive order enrolling 25,000 vets in the Civilian Conservation Corps, then, when they marched in Washington in May, sent his wife Eleanor out to meet them. She convinced many of them to sign on to work on one of Roosevelt’s grand public works projects – the southernmost portion of US Route 1, which would eventually become the Overseas Highway.

It might’ve ended there, but for the vagaries of South Florida’s weather: on September 2, 1935, the massive Labor Day Hurricane struck the vet’s worksite, killing 258. After that, public pressure saw a bonus bill once again introduced and passed by Congress, this time with enough votes to override FDR’s veto. So it was that in the election year of 1936, the veterans were finally paid their bonus – 18 years after the end of their war – but their legacy lived on. Memories of the Bonus Expeditionary Force played a part in the drafting of the GI Bill of Rights at the end of the Second World War, and it served as a model for later law-abiding large protests in the capital.

But perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Bonus March was the one it left upon its generation. For the veterans of the Great War, like those of Vietnam and Iraq long after, there are some historical lessons that just don’t seem to get learned – like the one about how “CEO presidents,” no matter how stirringly patriotic their speechification, are never, ever able to rise above their view of soldiers as nothing more than a single-use commodity.

Historiorant:

Apologies for being a night late with this – while you’ve all been off enjoying one another’s company at Netroots Nation, your resident historiorantologist has been busily painting the exterior of the Cave, and lemme tell you: it’s been every bit as easy as “painting the exterior of a cave” sounds.

Thanks, too, to those who attended the Daily Kos Meet N’ Greet at the Origins Game Fair in Columbus a couple of weeks ago. A good time was had by all throughout the convention, and the launch of newly-published books by Swordsmith and, um… myself went well indeed. Still hard to believe that a few Daily Kos diaries could wind up becoming a history book/role-playing game scenario with an ISBN and everything – but it’s exactly the sort of story that makes this site so much fun.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

11 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

but I saw that Nightprowlkitty’s piece had been promoted recently, and I wanted to ensure that it had its time to bask in the sun.

It seems as if we have a historical habit of shitting on veterans.

I love your historiorants. You are terrific, Moonbat!

…I need to know…Thanks!