WANTED: Extraterritorial location for indefinite detentions, torture of prisoners, and gigantic secret military installation. Island preferred, remoteness a plus; must be cleared of troublesome natives and provide for completely restricted access. Ideal landlord would consist of a compliant allied government willing to eat up the obvious bullshit that we’re going to spew trying to explain the patently illegal actions we carry out on their territory.

Contact: D. Vader, US Naval Observatory. Seriously corrupt inquiries only.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where our old ally Great Britain will answer the above ad – by cravenly permitting the United States to reverse-colonize Her Majesty’s empire on the island of Diego Garcia. Upon (and in the waters near to) this speck of coral in the Indian Ocean, the British and Americans have established a base/prison/human rights deprivation facility that has played a larger role in the Global War of Terror than even Guantanamo Bay – a fact to which the Brits, at least, are finally growing wise.

The Footprint of Freedom

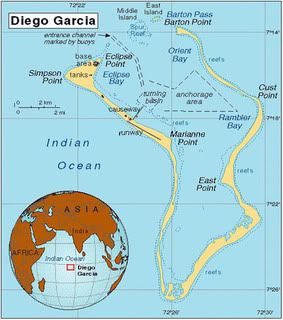

Seriously: that’s what the U.S. Navy has nicknamed it. The moniker is ironic only in the Orwellian sense – Diego Garcia atoll itself does kind of look like a footprint. It’s in the middle of nowhere, halfway between Tanzania and Java and about 1000 miles southwest of India and Sri Lanka, 300 south of the Maldives. Put another way, the bombing missions launched against Afghanistan from Diego Garcia’s massive 12,000-foot runway deal with roughly the same distances as an attack on Lima, Peru, that originated in Chicago.

Diego Garcia is the largest (at 12 square miles) of the 60-or-so islands in the Chagos Archipelago, an uninhabited chain comprising about around 36 square miles of land area and about 32,640 of ocean. Diego Garcia’s total area, about 66 square miles, encompasses a 48 square mile lagoon (up to 100′ deep) and 6.5 of peripheral reef. For all you absolute location junkies out there, the archipelago lies between 4°25′ and 7°39′ South latitude, 70°14′ to 72°37′ East longitude. Diego Garcia, or “DGar,” itself is the southernmost unsubmerged island of the chain, at 7°18’48″S, 72°24’40″E.

(a more detailed map of Diego’s named features can be found here)

The Chagos are a good example of the proverbial “desert islands,” even if the vegetation is invariably described in available literature as “lush” and their indigenous life includes the gigantic, 6+-pound coconut crab, the largest terrestrial arthropod known to exist. Being atolls, the islands are comprised of sand-topped coral, and barely reach altitudes above sea level – the highest point in the chain, at 22 feet, is on Diego Garcia. It wasn’t lack of adequate vantage point that kept the place devoid of human habitation, though – it was the lack of decent sources of fresh water.

Their seclusion makes the Chagos a destination for yachting enthusiasts in the know, who seem to enjoy exploring the ruins of colonial plantations and stringing hammocks between the palm trees – so long as they don’t wander anywhere near the black site shores of Diego Garcia, the military leaves them alone. Its isolation has also made it an ideal haven for wildlife: all flora and fauna are protected under the strict regulations of the British Indian Ocean Territory (a/k/a “B.I.O.T.,” a special, and probably illegal, Cold War-era spawn of the Empire), and Diego Garcia was added to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance on July 4, 2001. It may not be swampy, but at 102 inches of rainfall annually and consistently high humidity, it definitely qualifies as “wet land.”

Weird Mark H-type Sidenote: Those coconut crabs don’t mess around – they get their name from having claws powerful enough to husk and open coconuts. They’ve also been seen lifting logs and such in excess of 50 pounds, but don’t start thinking about how pincers like that might taste slathered in butter: the Brits impose heavy fines on anyone caught messing with one, alive or dead.

Weird Mark H-type Sidenote: Those coconut crabs don’t mess around – they get their name from having claws powerful enough to husk and open coconuts. They’ve also been seen lifting logs and such in excess of 50 pounds, but don’t start thinking about how pincers like that might taste slathered in butter: the Brits impose heavy fines on anyone caught messing with one, alive or dead.

The (Coconut) Oil Islands

The irony of adding DGar to a list of protected wetlands under a treaty negotiated in Iran in the early 1970s was neither the first, nor the last, incidence of bizarro-world naming the island has experience the island has endured. As for its official moniker, Diego Garcia was “discovered” in the European sense – kinda hard to believe that Zheng He, at least, didn’t know about them – in the early 1500s by those intrepid Africa-rounders, the Portuguese. The controversy over just who got to lay claim to the uninhabitable spit of sand seems to have started almost immediately:

Some historians believe that two separate ship’s captains laid claim to the discovery within one day in Portugal. Each of the two captains last names were used to name the island. Another school believes that Diego Garcia was the complete name of one ship’s captain or navigator.

US Naval Computer and Telecommunications Station Far East Detachment

Back in those days, the same morality that smiled upon mass racial slavery meant that there was little need to conduct torture in remote and inaccessible corners of the globe – in fact, state-sanctioned “enhanced interrogation” often had a public component to it. After British captain Sir James Lancaster reported a near-disaster on what was probably the Chagos Bank in 1602, no European got anywhere near the place for more than 100 years. The Portuguese didn’t settle Diego Garcia in any meaningful way, and by the end of the 18th century, their ancient claim to the island failed to restrain the French from sailing over from Mauritius and planting their own flag.

It didn’t stop the British from planting theirs, either. In 1774, the British ship Drake had dropped off pigs, sheep, and goats so as to form a feral larder for future shipwreck victims, and in 1786, the redcoats returned in force – more than 200 Brits and Indian Sepoys brought with them six shiploads of topsoil, so a to create a “victualing station.” Regrettably, the animals left by Drake could no longer be counted upon as a food source, having been consumed by a group of “straggling Frenchmen” who had built a few huts in a pathetic attempt at colonization in 1785. When the British arrived, they quickly packed up and sailed to Mauritius to inform the governor that France had just gotten a bit smaller, but the French returned in late 1786 to chase off the British. They found they’d already left of their own accord, the experiment in agriculture having failed because a shipwreck had dropped upon them an extra 250 mouths to feed.

France started marooning lepers on Diego Garcia in the late 1780s, where they took to eating sea turtles in the belief that the meat would cure them. In 1792, a British merchant captain sent two crew members ashore to speak with whoever was ashore, but when they returned and reported that there were 8 or 10 lepers on the island, the captain refused to let them back on board and sailed away, marooning them. The following year, a French investor was granted a coconut oil “concession” on Diego Garcia, but elected to ship coconuts to Mauritius for processing, owing to DGar’s potential vulnerability to British raiding. By 1824, there were four large coconut plantations on the island, and the French had imported slaves to work them – their descendents went on to become the closest thing the archipelago has to an indigenous population, which, as we shall see, entitled them to all the tender, loving care that native groups around the world have come to expect from Her Britannic Majesty.

Weird Historical Sidenote: That first plantation was established at a place called Eclipse Point. It’s the site of the base Officer’s Club today.

In the end, the Brits got the coconuts, the oil, Mauritius, and Diego Garcia anyway, when the 1814 Treaty of Paris dismembered Napoleon’s empire and sent him packing to Elba. Governed as a lesser dependency of Mauritius, the British essentially left the French in charge of their plantations, only occasionally checking in to see that imperial edicts from London were being carried out. Sometimes it took a little while for some of the more progressive of Britain’s reform laws to take root that far from the crown, however: when Britain abolished slavery in 1834, plantation owners responded by involuntarily “apprenticing” the newly-emancipated workers to a further 6 years of servitude.

Weird Historical Sidenote: The ex-slaves weren’t notified of their changed status until a 2-day visit by a British colonial official in 1838. As a result of his report, donkeys were imported to the island – the new law forbade humans doing work that could be done by beasts of burden – in 1840. Their feral descendents can still be found wandering the island today.

By the mid-19th century, the lepers had been evacuated to better facilities in Mauritius, and the colony’s population numbered around 350 (20 or so of whom were European, the remainder African and Indian plantation workers), plus an equal number of donkeys. The place got more populous in the latter half of the century, when Diego Garcia became a coaling station for two competing steamer lines, and laborers were imported from India, China, and Africa to man the shovels. Reading the histories, one gets the impression that Diego Garcia in those days was a monotonously bizarre place:

By the mid-19th century, the lepers had been evacuated to better facilities in Mauritius, and the colony’s population numbered around 350 (20 or so of whom were European, the remainder African and Indian plantation workers), plus an equal number of donkeys. The place got more populous in the latter half of the century, when Diego Garcia became a coaling station for two competing steamer lines, and laborers were imported from India, China, and Africa to man the shovels. Reading the histories, one gets the impression that Diego Garcia in those days was a monotonously bizarre place:

1875 E. Parkenham Brooks, the first colonial official to visit since 1859, fined the Manager of the East Point Plantation, James Spurs, for imprisoning three ‘labourers’ without sufficient cause. He also fined an under-manager at Point Marianne for striking a labourer.

1884 Captain Raymond, of the sailing ship WINDSOR CASTLE, which had arrived with 1,334 tons of coal for Lund and Company, gets drunk, lands at East Point with 16 armed men, takes pot shots at what he thought was Spur’s house (which was unoccupied), nails the Union Jack on a nearby palm tree, and claims the (already British) island for Great Britain. He sobers up two days later, and sails away. No one else in the history of Diego Garcia ever got quite that drunk. Except maybe one or two people once or twice.

1886 Louis Fidele is imprisoned for practicing witchcraft in the cemetery at East Point. This witchcraft was intended to ensure that the ghosts would not rise up to haunt the living, which was a very real fear of the workers on the island.

1888 The coaling stations on the island close, their rowdy employees depart, and steamships stop stopping. No longer needed to police the wild crowds of imported Somalis, Indians and Chinese manning the stations, Mister Butler and his Constables are withdrawn, and no other police force was set up for the next 85 years. The island is left to the workers and European overseers of the plantations.

Important Dates of the Provisional People’s Democratic Republic of Diego Garcia

A New Century Slow in Coming

A great example of how the island’s remoteness could be used for wartime sleight of hand came in early October, 1914, when one of the Kaiser’s cruisers, SMS Emden, steamed into DGar’s lagoon. The ship spent two days there, defenseless while her crew scraped barnacles from her hull; not long afterward, a pair of British ships arrived and told the plantation owners that the Great War had begun three months earlier – and that they should keep their eyes peeled for Emden. (do click the link – Emden’s got an incredible story)

Other than that, World War One (which isn’t really known for its naval battles, after all) didn’t stretch quite as far as Diego’s shores, and little of note came to pass during the couple of decades afterwards, either. The Indian Ocean was essentially a British lake at that point, so London must’ve figured that if a few holdout Frenchman want to recall the days of empire by growing coconuts on an island in the middle of it, then more power to ’em. White Man’s Burden, and all that.

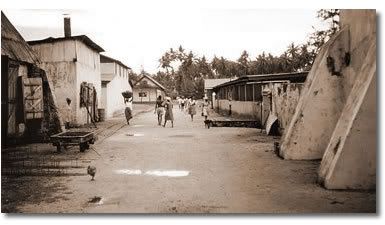

The plantations had, by that point, developed into a small but thriving community. A “railroad” of carts pulled by donkeys linked various parts of the island to the various coconut processing facilities, docks, and residential areas. Estimates range from 800 to 2000 descendents of those first few African slaves and imported Indian laborers from more than a century before, and they had, as successive generations of an isolated group tend to do, become a culture in their own right. There were various attempts to Christianize them – a crumbling chapel sits amidst the ruins of the plantation to this day – but for the most part, the Chagossians (a name which came to be applied later) worshipped much as had their ancestors. They moved freely about the islands – two other atolls had permanent communities – dividing their time between subsistence farming, fishing, and working on the coconut plantations. (good pics and story about the East Point Plantation from the perspective of a guy who was stationed at Diego Garcia in the early 80s available here)

The plantations had, by that point, developed into a small but thriving community. A “railroad” of carts pulled by donkeys linked various parts of the island to the various coconut processing facilities, docks, and residential areas. Estimates range from 800 to 2000 descendents of those first few African slaves and imported Indian laborers from more than a century before, and they had, as successive generations of an isolated group tend to do, become a culture in their own right. There were various attempts to Christianize them – a crumbling chapel sits amidst the ruins of the plantation to this day – but for the most part, the Chagossians (a name which came to be applied later) worshipped much as had their ancestors. They moved freely about the islands – two other atolls had permanent communities – dividing their time between subsistence farming, fishing, and working on the coconut plantations. (good pics and story about the East Point Plantation from the perspective of a guy who was stationed at Diego Garcia in the early 80s available here)

Diego Garcia was a bit more strategically important during the Second World War. A base for PBY Catalina seaplanes was begun in March, 1941, and became operational a year later. In addition to ‘sectionalised huttery,’ the RAF brought with it engineers and materials to significantly develop the island: a road, complete with concrete bridges, was constructed around the lagoon’s perimeter, and 6-inch naval rifles were emplaced at the harbor entrance. For the remainder of the war, Diego Garcia served as a recon and emergency repair base for the fierce combat between Japanese subs, armed merchantmen, German U-boats, and surface ships from a smattering of Allied nations. Among the more infamous of the adversaries they faced was the murderous war criminal Tetsunosuke Ariizumi and the bloodthirsty crew of the I-8, when Catalinas from Diego Garcia were charged with finding survivors of the sub’s various massacres.

The Empire Strikes Back

The Catalinas, sailors, and soldiers went home at war’s end, and Diego Garcia once again dropped off the face of the map. To wit: while Americans were fighting the Chinese in Korea, the island celebrated the opening of its first school. The remainder of the 1950s saw little but visits from colonial officials, ichthyologists, and (significantly) survey teams from the RAF. In the settlements, the economy reflected the principles common on remote islands everywhere – one visitor in 1955 reported that a chicken could be bought for three imported cigarettes – but there could be little denying that culturally, the nearly 2000 islanders of the Chagos Archipelago had formed a distinct creole identity that stretched back at least five generations.

That fact (and the evidence, such as headstones in cemeteries, which proved it) would become inconvenient a few years later, when British Prime Minister Harold Wilson obsequiously served up the islands to a United States in a land-seizure plot truly breathtaking in its diplomatic barbarity. In the early 1960s, US strategic concerns about the Soviets in the Indian Ocean compelled the construction of a new naval base, and though the first choice, Aldabra (north of Madagascar), was nixed because it was the breeding ground for a rare tortoise, Diego Garcia represented an outstanding runner-up.

Historiorant: Really, its location – about equidistant from several chronic world hotspots – made Diego Garcia a better choice from the start, except that there were, um, people living on it. And regarding Aldabra, the decision wasn’t made based on empathy for the tortoise; rather, Pentagon types figured that outraged environmentalists would shed too much light on happenings at the secret facility.

The machinations that would deliver Diego Garcia into American hands for the next 50 years (with an option for another 20) began under the Johnson administration, and were concluded during Nixon’s; in the U.K., Wilson’s Labour government was succeeded in 1970 by Edward Heath and the Conservatives. Both nations came to the same conclusion vis-à-vis the residents of the Chagos islands: the people would have to go. That this contravened a number of the founding documents of the United Nations seemed to bug them more for the possibility of getting caught than out of some sense of morality, though the Brits hemmed and hawed (a little) at taking treatment-of-natives lessons from the Americans. In the end, the Brits met the issue in the same head-on way that they would deal with later accusations that the US had been torturing people on their island:

“We recognize that we are in a difficult position as regards references to people at present on the detached islands. We know that a few were born in Diego Garcia and perhaps some of the other islands, and so were their parents before them. We cannot therefore assert that there are no permanent inhabitants, however much this would have been to our advantage. In these circumstances, we think it would be best to avoid all references to permanent inhabitants.”

Telegram from Foreign Office to UK mission at the UN, November, 1965 — BBC, 3 November, 2000

Once they’d decided to ignore the human beings they’d sworn to protect, though, the British forgot about them somethin’ fierce:

“We must surely be very tough about this. The object of the exercise is to get some rocks which will remain ours… There will be no indigenous population except seagulls…”

Sir Paul Gore-Booth. Foreign Office, 1966 — ibid. The reply, gathered from this site, included the following:

“Unfortunately along with the birds go some few Tarzans or Man Fridays whose origins are obscure and who are hopefully being wished on to Mauritius.”

Those “rocks” had traditionally “belonged” to Mauritius, as that was where the colonial seat lay, but they remained noticeably not-Mauritian when the islands were granted their independence in 1965 – the Chagos Archipelago remained in the UK’s hands as the newly-created British Indian Ocean Territory. This move – the Territory was created via Order in Council – was patently illegal (various UN resolutions regarding de-colonization prohibited slicing off chunks of soon-to-be-freed lands), but the Brits were enticed to look the other way rather cheaply – $14 million in forgiven loans related to their Polaris missile projects. And as for the Queen’s newest subjects, the Chagossians (also known as the Ilois)? Well, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, no one can hear you scream.

Those “rocks” had traditionally “belonged” to Mauritius, as that was where the colonial seat lay, but they remained noticeably not-Mauritian when the islands were granted their independence in 1965 – the Chagos Archipelago remained in the UK’s hands as the newly-created British Indian Ocean Territory. This move – the Territory was created via Order in Council – was patently illegal (various UN resolutions regarding de-colonization prohibited slicing off chunks of soon-to-be-freed lands), but the Brits were enticed to look the other way rather cheaply – $14 million in forgiven loans related to their Polaris missile projects. And as for the Queen’s newest subjects, the Chagossians (also known as the Ilois)? Well, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, no one can hear you scream.

The Politics of Building a Stationary Aircraft Carrier

The removals began innocuously enough – people who left the islands for, say, medical treatment were simply not allowed to return. This violates several provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, notably this one:

Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to

return to his country.— Article 13, Section 2

Concurrent with non-return policy was an official line that there were, in fact, no long-term inhabitants of the islands, to say nothing of an indigenous population. The Chagossians, when they were talked about at all, were referred to as “migrant workers” who moved from island to island, never as a generations-old group of residents. This fiction can be seen today, in such sources as the CIA World Factbook entry regarding BIOT’s “Population”:

no indigenous inhabitants

note: approximately 1,200 former agricultural workers resident in the Chagos Archipelago, often referred to as Chagossians or Ilois, were relocated to Mauritius and the Seychelles in the 1960s and 1970s; in November 2000 they were granted the right of return by a British High Court ruling, though no timetable has been set; in November 2004, approximately 4,000 UK and US military personnel and civilian contractors were living on the island of Diego Garcia

There’s a bit more to it than that.

For one, the CIA notes nothing about the relocation, which was not at all voluntary. Sir Bruce Greatbatch, governor of the Seychelles, was given the task of “santising” the island as American Seabee engineers arrived. To force the reluctant islanders to get into the cargo holds of the ships that would take them to exile (horses got to ride on the deck), Greatbatch ordered more than 1000 pet dogs rounded up, then asphyxiated them using the exhaust from American trucks in a furnace in the middle of a workplace, sending a clear warning that was not lost upon the natives.

Throughout 1971 and 1972, the Chagossians were exiled on the unwelcoming shores of other Indian Ocean islands. Some were conveyed first to the Seychelles, held in a prison until being transported to Mauritius, and abandoned on the dock to fend for themselves; in the end, most wound up living in the slums of Port Louis, the Mauritanian capital. With no more than a suitcase of possessions apiece, and very little money, the Chagossians quickly found themselves on the bottom rung of the Mauritius socio-economic ladder.

Not unlike the ends of other trails of tears, hitherto-unknown social problems and rampant drug abuse soon afflicted the small community, and the majority of them have lived in abject poverty ever since. The similarities to 19th century US Indian policy don’t end there: the Chagossians were “compensated” to the tune of £650,000 in 1973 (most of the money is said to have disappeared after being handed over to the Hindu-majority Mauritius government for distribution to the animist Ilois), with a further £4 million (about £3000 per person) dangled before them in the 1980s – but with the provision that they sign a document renouncing any further claims to compensation or right of return. Perhaps it’s just an irony that around the same time, Margaret Thatcher was deploying aircraft carriers and invasion forces to “defend the rights” of the Falkland Islanders from the depredations of the Evil Argentines – for, as the Daily Telegraph reminded the freedom-loving peoples of the world, we must not “be indifferent to the imposition of foreign rule on people who have no desire for it.”

Various lawsuits through the years (pdf) have sought to remedy the Chagossian situation over nearly forty years of exile. In general, the courts have found on behalf of the islanders, but the British and American governments have taken a thoroughly Jacksonian approach to the rulings: basically, the courts can rule however they please, because the government’s going to do what it wants anyway.

In 1972 the US Defense Department assured Congress that “the islands are virtually uninhabited and the erection of the base would thus cause no indigenous political problems.” When asked about the native population, a British Ministry of Defence official said: “There is nothing in our files about inhabitants or about an evacuation.”

There has been some forward momentum for the Chagossians over the past decade: In 2000, the High Court upheld their claim that their removal had been unlawful, and in 2002, Parliament backed them up with legislation granting the Chagossians British citizenship, among other things. By 2003, the Court seemed well aware of the islander’s plight:

The Ilois [Chagossians] were experienced in working on coconut plantations but lacked other employment experience. They were largely illiterate and spoke only Creole. Some had relatives with whom they could stay for a while; some had savings from their wages; some received social security, but extreme poverty routinely marked their lives. Mauritius already itself experienced high unemployment and considerable poverty. Jobs, including very low paid domestic service, were hard to find. The Ilois were marked by their poverty and background for insults and discrimination. Their diet, when they could eat, was very different from what they were used to. They were unused to having to fend for themselves in finding jobs and accommodation and they had little enough with which to do either. The contrast with the simple island life which they had left behind could scarcely have been more marked.”

Since the Foreign Office had been dragging its feet, the Chagossians returned to court that same year seeking additional compensation, but this time were handed a reverse – the High Court found they’d been paid enough. The Blair government then arranged (in 2004) for Orders-in-Council that reversed the Court’s 2000 decision and banned the Chagossians from ever returning, but these were struck down by the High Court in 2006. In April of that year, 102 Chagossians were permitted a brief visit (under strict British supervision) to the East Point Plantation site to tend to the graves of their ancestors, but their legal status remains enmeshed in the British legal system, attempts at justice made through American courts having been quickly dismissed.

Since the Foreign Office had been dragging its feet, the Chagossians returned to court that same year seeking additional compensation, but this time were handed a reverse – the High Court found they’d been paid enough. The Blair government then arranged (in 2004) for Orders-in-Council that reversed the Court’s 2000 decision and banned the Chagossians from ever returning, but these were struck down by the High Court in 2006. In April of that year, 102 Chagossians were permitted a brief visit (under strict British supervision) to the East Point Plantation site to tend to the graves of their ancestors, but their legal status remains enmeshed in the British legal system, attempts at justice made through American courts having been quickly dismissed.

Historiorant: There’s actually a fair amount of stuff on the Chagossians out there, but it’s in disparate places and the group has always had difficulty getting its message out – hell, they’ve even had difficulty, as British citizens, of obtaining housing in Britain itself. World History Archives has a decent collection, especially of Guardian articles, as does this site; YouTube‘s search page is a good starting place for vids.

DGar Goes to War

The first nine-man detachment of Seabees arrived in January, 1971, and were followed a couple of months later by a whole boatload of them (the ship, incidentally, had been painted white, to reflect peacetime deployment to an allied territory). The first runway, only 3500 feet long, was completed in July; by November, it had stretched to 6000 feet, and was accompanied by a communications array and a tent city of busy Seabees (the 1970s construction efforts at Diego Garcia represent the largest peacetime project in Seabee history). Construction, civilian evictions, and dog massacres continued apace for two years – the first jet to land on Diego Garcia arrived on Christmas Day, 1972, carrying Bob Hope and a USO tour – and by 1977, a US Naval Communications Station and a full-on US Naval Support Facility had been commissioned.

The first nine-man detachment of Seabees arrived in January, 1971, and were followed a couple of months later by a whole boatload of them (the ship, incidentally, had been painted white, to reflect peacetime deployment to an allied territory). The first runway, only 3500 feet long, was completed in July; by November, it had stretched to 6000 feet, and was accompanied by a communications array and a tent city of busy Seabees (the 1970s construction efforts at Diego Garcia represent the largest peacetime project in Seabee history). Construction, civilian evictions, and dog massacres continued apace for two years – the first jet to land on Diego Garcia arrived on Christmas Day, 1972, carrying Bob Hope and a USO tour – and by 1977, a US Naval Communications Station and a full-on US Naval Support Facility had been commissioned.

The base was one of the staging areas for the ill-fated Operation EAGLE CLAW attempt to end the Iran Hostage Crisis. In the early 80s, it became a staging area for SR-71 spy planes and KC-135 (later KC-10) refuelers, as well as the home of a Marine Corps brigades’ worth of arms and supplies, which is kept aboard Maritime Prepositioning Ship Squadron Two, a group of supply ships lying at anchor in Diego Garcia’s harbor (the Army maintains a small armada of prepositioned logistics ships there, as well). Interestingly, in 1982, the Houston firm of Kellog, Brown, and Root became one of three contractors awarded a total of 128 projects – costing $400,000,000 – for a massive expansion of Navy and Air Force facilities.

By 1985, even aircraft carriers were dwarfed by the gigantic new wharf, and the runway is now so long that it can accommodate any aircraft in the world (not to mention serves as one of 33 emergency landing sites for the Space Shuttle). Diego Garcia is also one of five control bases for the worldwide Global Positioning System (the others are in Hawaii, Kwajalein Atoll, Ascension Island, and Colorado Springs), and is home to all manner of eavesdropping and orbital spying units. When located near populated areas, these types of facilities are often sited in the most restricted parts of already restricted-access military bases; when they’re on an island like Diego Garcia, the security that attends them has the effect of shrouding the entire region in a cloak of mystery so thick that only a torturer could love it.

Diego Garcia played a major role in the Gulf War. The ships of USMC Prepositioned Ship Squadron Two sailed to Saudi Arabia beginning on August 7, 1990, where they met the 16,500 Marines of the 7th Expeditionary Brigade arriving by air. The logistics system worked like a military-industrial charm: the brigade was combat-ready by the 25th, though as things turned out, the war didn’t start until several months later. When it did, B-52s launched from Diego Garcia flew some of the initial sorties, and throughout the remainder of the 1990s, the bombers and their attendant KC-10s remained an asset of which Bill Clinton occasionally availed himself – as during Operation Desert Strike in 1996 and Operation Desert Fox in 1998, both of which targeted Iraq.

Afghanistan got a look at the underside of aircraft flying from Diego Garcia, too. Three days after the September 11 attacks, 10 B-52s and 8 B-1B bombers arrived; they and others like them were part of the initial thrust of Operation Enduring Freedom, launched on October 7. On the 8th, a flight of 3 B-2 Stealth bombers completed the longest bombing run in world history – 44 hours – when they took off from Missouri, dropped ordinance on Afghanistan, and landed at Diego Garcia. Later, in 2002-03, contractors built special climate-controlled hangers capable of housing B-2s, allowing the bombers to be based a little closer to the action than the midwestern United States. Throughout those early, heady days of the War on Nouns – when even the South Koreans deployed a unit to Diego Garcia – P-3 Orions heroically buzzed around the island on the lookout for Taliban submarines, protected overhead by the FA-18s of the Royal Australian Air Force, who stood at the ready to shoot down any plane of the al-Qaeda air force the American AWACS detected.

Camp Justice

When the Spanish boarded the unflagged, Yemen-bound North Korean merchantmen So San in December, 2002, and discovered 15 Scud missiles under a cargo of cement, the ship was turned over to the US and reportedly brought to Diego Garcia, but it seems that the crew weren’t the first prisoners of Mr. Bush’s War to find themselves moored off its shores. Since before the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom on March 21, 2003, there have been allegations that Diego Garcia had served as a “refueling station” for the rendition flights of terror “suspects” aboard Ghost Planes, and it seems likely that upwards of 15 Ghost Ships have anchored offshore at various times during the Neocon Conflict.

What went on in the holds of those ships, or in secluded, windowless buildings on shore, no one can – or, more accurately, will – say. Again, it’s been reporters from The Guardian that have done a bunch of the heavy lifting (though here’s a good one from AlterNet), piecing together reports from as early as December, 2001 (about upgrades to detention facilities) through Jack Straw’s lying through his teeth in 2004 (Friday October 19 2007), right up to this summer (The Observer, Sunday March 2 2008), when the years of lying finally began to unravel. There are some real gems in these reports – like why, exactly, the Blair government chose not to follow up on early reports of rendition flights and detentions at Diego Garcia:

UK officials are known to have questioned their American counterparts about the allegation several times over a period of more than three years, most recently last month. Whenever MPs have attempted to press ministers in the Commons, they have met with the same response: that the US authorities “have repeatedly given us assurances” that no terrorism suspects have been held there.

…and the growing sense of indignation at having their territory – which had been properly conquered and depopulated, in accordance with the ancient laws of imperialism – used as an extralegal torture haven by London’s swaggering ally:

Only time will tell the full extent of this collusion. The government has always denied allowing the Americans to use British soil for torture and abuse, but sceptics focus on the British territory of Diego Garcia, in the Indian Ocean. British denials are difficult to square with the words of US army general Barry McCaffrey, who had recently retired from running Southcom, the military command that oversees Guantánamo. He was asked in May 2004 where the thousands of ghost prisoners were being held.

“You know, Bagram Air Field, Diego Garcia, Guantánamo, 16 camps throughout Iraq,” he replied. Very recently, (human rights organization) Reprieve has discovered flight logs that confirm a CIA rendition plane flying into and out of the base at Diego Garcia.

On July 31, Meteor Blades compiled many more sources specifically related to extraordinary rendition and Diego Garcia – check out U.S. Diego Garcia Denials Take Another Hit for more documentation of American misdeeds and British complicity.

Historiorant:

It’s an odd irony that the country that gave us this:

It’s an odd irony that the country that gave us this:

No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his freehold,

or liberties… or exiled…but by the law of the land…

— The Magna Carta

would now selectively edit that august document with the same vigor as George W. Bush trashing the U.S. Constitution, but really, it’s no more ironic than this advice, provided as part of the welcome literature for new Navy arrivals at the base:

In accordance with current regulations, no type of attire with degrading or obscene comments may be worn on or brought to Diego Garcia. This includes pictures, phrases or slogans depicting drug paraphernalia, anti-war slogans, ethnic slurs or issues of a sexual nature. Biker, hippie-culture or mercenary magazines will be confiscated. All obscene or pornographic publications including pornographic videos will be confiscated. All videotapes brought to Diego Garcia will be retained by British Customs for screening. Tapes will be returned within 10 days. Prohibited material will be burned by British Customs.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

8 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

It’s surprising how much history can pile onto a 12 square mile atoll over the course of 500 years…

but I guess I’ll have to find another atoll to buy, huh. Don’t much like crabs anyhow, especially those that can lift 50 lbs.

This is somehow a rude thing to say, but your writing improves all the time, sir. As my brother-in-law the pianist says, “If you practice, it gets better” (Rob’s Law). Carry on, carry on.

thank you.

Empire is empire; always has been, always will be. We’re just the latest version of the red, white and blue. Then again, so is Russia. Oligarchs wherever you turn. It’s not so much ours and theirs as us and them.

Just for the lulz I Google-earthed DGar. They actually allow some detail. You can count the bombers on the tarmac. For a better laugh check out the US Navan Observatory in DC and Lord Cheney’s undisclosed location at Raven Rock, PA. Those were badly fudged out six months ago but now they’re totally indecipeherable. Looks like the USNO is especially pixelated. Just two months ago you could see blurry details of all the construction activity on the surface. The underground work is supposed to be running 24/7 and has been since the Dark Lord took residence.

I wonder if the complaints about the noise and trucks have been purged from past volumes of the local rags.

Somehow I don’t see Cheney leaving that all behind so easily. With Obama rapidly switching sides I don’t think we’ll ever see the light of day on the crimes committed in our names.

“From obscenity into obscenity, the Oligarchy unfolds.” RUKind, paraphrasing the Tao Te Ching

thank you.

It will be fascinating to see what comes to light on the change in governments, if we are to see a change, over the next few years.

Or maybe that was Alfredo.