A new study by researchers at Johns Hopkins has linked low level exposure of inorganic arsenic in drinking water supplies to the risk of type 2 diabetes. The new study indicates that environmental factors may play a role in type 2 diabetes in addition to other commonly recognized factors, such as body weight and inactivity. This is important because often our government says not to worry about particular pollutants or contaminants because the levels released into our water, soil and air are too low to be harmful to us.

A new study by researchers at Johns Hopkins has linked low level exposure of inorganic arsenic in drinking water supplies to the risk of type 2 diabetes. The new study indicates that environmental factors may play a role in type 2 diabetes in addition to other commonly recognized factors, such as body weight and inactivity. This is important because often our government says not to worry about particular pollutants or contaminants because the levels released into our water, soil and air are too low to be harmful to us.

The EPA has already linked arsenic in drinking water to various cancers, such as “cancer of the bladder, lungs, skin, kidney, nasal passages, liver, and prostate” and to noncancer effects and illnesses, such as “thickening and discoloration of the skin, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting; diarrhea; numbness in hands and feet; partial paralysis; and blindness.” And, in regions where there are high levels of arsenic in water supplies and the environment, it has been linked to cardiovascular health and diabetes. Regions that are “highly contaminated” include Bangladesh, Taiwan and Chile.

However, this John Hopkins study found that persons “exposed to low and moderate levels of inorganic arsenic, found in certain areas of the United States, may increase the risk of diabetes.”

The Hopkins researchers analyzed arsenic concentrations in urine samples of 788 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants. After adjusting for other risk factors for diabetes and for harmless organic arsenic ingested by eating fish, the researchers found that participants with type 2 diabetes had a 26% higher level of inorganic arsenic than those who didn’t have the disease.

The study found “a nearly fourfold increase in the risk of diabetes in people with low arsenic concentrations in their urine compared to people with even lower levels.”

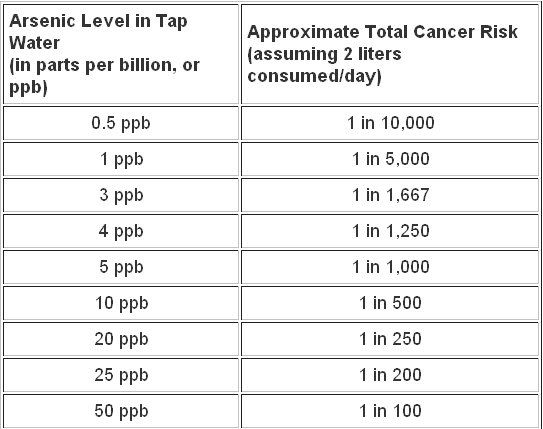

In 2001, due to known cancer risks, the EPA lowered arsenic levels in drinking water supplies to 10 parts per billion (pdf file), which the EPA describes as the “equivalent of a few drops of ink in an Olympic-size pool.” However, as the chart below shows, that little bit of ink means a 1 in 500 risk of cancer. The EPA mandated compliance by 2006 with this new standard, which would provide “additional protection” to an “estimated 13 million Americans.” The 13 million Americans represents those customers served by 5% of community water systems (cities, apartment buildings, mobile home parks) and non-community water systems (schools, churches, nursing homes and factories) which needed to take “corrective actions” to lower arsenic levels in their drinking water. The EPA and one author of the Johns Hopkins study disagree as to whether we now have compliance with the 10 ppb standard. While the Johns Hopkins data was compiled in 2003 and 2004 or before the 2006 deadline, one author stated that the study shows that “more than 13 million Americans are living in areas with arsenic levels above that” EPA standard of 10 ppb.

One question is whether 10 parts per billion is a sufficient standard. A 2001 report stated that the prior federal standard had been 50 parts per billion which was linked to “high risks of cancer,” but also noted that people who “consume water containing 3 parts per billion of arsenic daily have about a 1 in 1,000 increased risk of developing bladder or lung cancer during their lifetime.”

In 2001, the NRDC had similar results, which showed that in terms of total cancer risk, 50 ppb risked 1 in 100, 10 ppb is 1 in 500 and 3 ppb is 1 in 1,667:

In 2001, the NRDC suggested a standard of 3 ppb because most testing labs can reliably detect arsenic at that level.

As the lead study author said, “The good news is, this is preventable.” But, will our government take action? One factor in answering that question is how much is a life worth? The EPA recently answered:

The “value of a statistical life” is $6.9 million in today’s dollars, the Environmental Protection Agency reckoned in May – a drop of nearly $1 million from just five years ago.

When drawing up regulations, government agencies put a value on human life and then weigh the costs versus the lifesaving benefits of a proposed rule. The less a life is worth to the government, the less the need for a regulation, such as tighter restrictions on pollution.

Consider, for example, a hypothetical regulation that costs $18 billion to enforce but will prevent 2,500 deaths. At $7.8 million per person (the old figure), the lifesaving benefits outweigh the costs. But at $6.9 million per person, the rule costs more than the lives it saves, so it may not be adopted.

Another issue affecting the chances of lowering the standard more is the sources of inorganic arsenic. It is an industrial pollutant “from coal burning and copper smelting.” Additional sources include “releases from its use as a wood preservative, in semi-conductors and paints, and from mining and agricultural operations (pdf file).” US industries release thousands of pounds into the environment every year. It also can be “found naturally in rocks and soil.” Congress would be hit by lobbying by industrial groups as well as water agencies which may not wish to comply with increased water quality standards.

A new study is underway of 4,000 people. The results will clearly be based on the new EPA standard and the researchers say that “new safe drinking water standards may be needed if the findings are duplicated.”

2 comments

Author

this is a common issue not addressed by studies before of the impact of low level exposure. let’s hope more studies are conducted.