Mention the term “Luddite” to most folks nowadays, and it’ll conjure up images of John McCain types – elderly folks still mystified by the electric typewriter, with “12:00” blinking perpetually on their VCRs – or the hard-core back-to-the-Earth sorts, who bristle at any device with moving parts. As usual, the actual history is far more complex: these “frame-breakers” of early 19th-century England were not a variant on Amish farmers given over to vandalism, but rather the product of a complicated confluence of occurrences involving everything from newfangled labor-saving machines to the Napoleonic Wars.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll take a look inside the changing marketplace at the dawn of the 1800s – and at a group of folks who tried to plow the sea by attempting to arrest the flow of history.

The Green Green Hills of Home

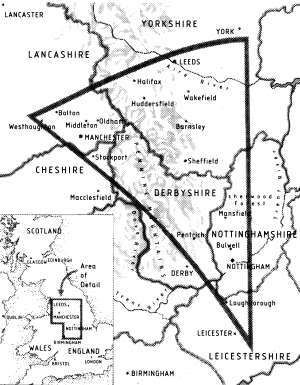

The story of the Luddites is set in the central part of England, around Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Cheshire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Flintshire, between March 1811 and April 1817. This was traditionally the home of England’s textile industry, a place where artisans knit stockings in one piece, without seams, for both export and domestic consumption. They were among the best in the world at what they did, and were organized under laws and customs dating back centuries into a kind of contract system in which “factors” (from the Latin “he who does”) delivered raw materials and picked up finished goods at artisan’s cottages on a set schedule.

The story of the Luddites is set in the central part of England, around Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Cheshire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Flintshire, between March 1811 and April 1817. This was traditionally the home of England’s textile industry, a place where artisans knit stockings in one piece, without seams, for both export and domestic consumption. They were among the best in the world at what they did, and were organized under laws and customs dating back centuries into a kind of contract system in which “factors” (from the Latin “he who does”) delivered raw materials and picked up finished goods at artisan’s cottages on a set schedule.

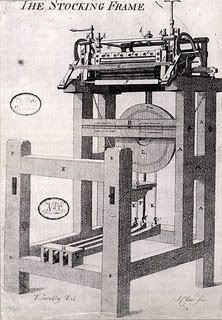

In a 1984 essay entitled Is it O.K. to be a Luddite?, Thomas Pynchon related a legend about the first threat to the slow, craftsman-based knitting system in these regional “manufactories.” It seems that in 1589 or so, a cleric by the name of William Lee was in love with a young lady who worked in the cottage hosiery industry, and he learned to his great chagrin that while folks may indeed have been working at home, knitting socks was still a full-time occupation. When the Reverend’s afternoon-delight advances were spurned due to his love’s workload, he proceeded to conceptualize and invent a frame-loom that, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, “was so perfect in its conception that it continued to be the only mechanical means of knitting for hundreds of years.”

So began the long, slow burn of resentment toward the automation of the knitting process that would culminate in the Luddite Revolt. This isn’t to say that the Luddites were the first unemployed workers to destroy offending machines – as early as 1675, weavers in Spitalfields were trashing “engines” that were replacing flesh-and-blood workers, and in 1710 a London manufacturer found his digs destroyed for employing too many apprentices, in violation of the Framework Knitters Charter. This and other similar events led historioranter E. J. Hobsbawm to define these actions as “collective bargaining by riot.”

Across the sea, the American colonists might’ve been agitating for revolt based on their own problems with the Crown, but the late 18th century was a pretty turbulent time on the English domestic scene, too. In 1768, London sawyers attacked a machine-driven sawmill; ten years later, stockingers in Nottingham rioted when Parliament failed to pass a law regulating “the Art and Mystery of Framework Knitting.” In 1792, in what might have been the most expensive act of anti-mechanical vandalism prior to the rise of the Luddites, workers in Manchester rose up against more than 20 steam looms owned by early industrialist George Grimshaw.

Weird Historical Sidenote: The destruction of machines as a means of expressing displeasure at the contemporary social order was not unique to England, as we were reminded by Lt. Valeris in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country:

Four-hundred years ago, on the planet Earth, (French) workers who felt their livelihood threatened by automation, flung their wooden shoes, called sabot, into the machines to stop them . . . hence the word: sabotage.

Here we find proof that even Vulcans can get their facts mixed up: though this is the most popularly known (and Ludd-esque) explanation for the word “sabotage,” there are others that seem more likely. For example, during a railway strike in 1910, workers destroyed the wooden “shoes” (i.e., the ties) that held the rails in place, so as to pressure company officials by stranding commuters; still another etymology involves the use of strikebreakers from the countryside, who still wore unfashionable wooden shoes, and whose slow, sloppy work on the machines came to be imitated by leather-shoe-wearing urban workers whenever they needed to get a point across to management.

“Ned Ludd Did It.”

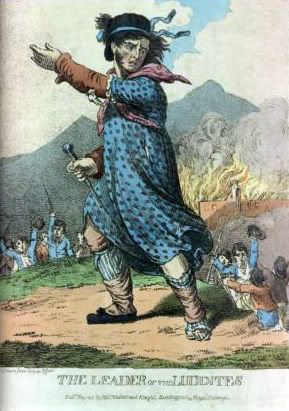

There may well have been an actual Ned Ludd in 1779, and he may well have destroyed two stocking frames in Anstey, Leicestershire – but if so, he’s got a lot in common with Kilroy, whom we all remember Styx describing as “Just a man whose circumstances/Went beyond his control.” The sources which describe Ned Ludd (or Ludlam) almost invariably refer to him as a “simpleton,” which in the 18th century described conditions we now refer to as “developmental disabilities.” Given this, a plausible-sounding picture of the real Ned Ludd emerges: he wasn’t some activist technophobe attempting to launch a visionary campaign against the ramifications of the Industrial Revolution upon existing socioeconomic order – rather, he was a kid with an IQ of 60 or so, ordered to perform a complex task using a machine he had no hope of ever understanding, and pressured by slavedriving bosses until he got frustrated and threw a loom-wrecking tantrum.

There may well have been an actual Ned Ludd in 1779, and he may well have destroyed two stocking frames in Anstey, Leicestershire – but if so, he’s got a lot in common with Kilroy, whom we all remember Styx describing as “Just a man whose circumstances/Went beyond his control.” The sources which describe Ned Ludd (or Ludlam) almost invariably refer to him as a “simpleton,” which in the 18th century described conditions we now refer to as “developmental disabilities.” Given this, a plausible-sounding picture of the real Ned Ludd emerges: he wasn’t some activist technophobe attempting to launch a visionary campaign against the ramifications of the Industrial Revolution upon existing socioeconomic order – rather, he was a kid with an IQ of 60 or so, ordered to perform a complex task using a machine he had no hope of ever understanding, and pressured by slavedriving bosses until he got frustrated and threw a loom-wrecking tantrum.

Ned Ludd as a person disappears from history shortly after he was presumably fired (or worse), but as a symbol, he grew and grew. He was the scapegoat-of-first-resort for acts of sabotage – “I didn’t do it; Ned Ludd did!” – and, eventually, “Captain” or “General” Ludd, ne’er-seen folk hero from the woods that begat Robin Hood, and the cryptic signature at the bottom of certain letters received by area mill-owners. Naturally, he rates a folk ballad – General Ludd’s Triumph has been recorded as recently as 1985:

Chant no more your old rhymes about bold Robin Hood,

His feats I but little admire

I will sing the Achievements of General Ludd

Now the Hero of Nottinghamshire

Brave Ludd was to measures of violence unused

Till his sufferings became so severe

That at last to defend his own Interest he rous’d

And for the great work did prepareNow by force unsubdued, and by threats undismay’d

Death itself can’t his ardour repress

The presence of Armies can’t make him afraid

Nor impede his career of success

Whilst the news of his conquests is spread far and near

How his Enemies take the alarm

His courage, his fortitude, strikes them with fear

For they dread his Omnipotent Arm!

In the end, it would take entire armies to subdue the irate craftsmen who vandalized under the cloak of Ned Ludd’s name. Ironic, that.

When the Modern Economy was Young

There are as many explanations for the Luddite Revolt as there are socioeconomic historians who have heard of it. Most agree that the 1808 Orders in Council drawn up by Spencer Perceval (who, beginning in 1809, would be serving as Prime Minister during the runup to the 1812 war with the United States and the start of the Luddite uprising) had a lot to do with it. Designed to retaliate against Napoleon’s Continental System, which declared that no French ally or subject was allowed to trade with the British, the Orders in Council declared that the King was going to blockade their stupid trade anyway – and their bigger, badder navy was able to walk London’s talk.

Despite their eventual more-or-less-success on the strategic level, however, the Orders-in-Council had a devastating effect on the economy closer to home. Food prices rose even as manufactories were forced to compete for orders in a domestic-consumption-only market (Thomas Jefferson’s dambargo might’ve been ill-advised and poorly enforced, but it did cut back on hosiery exports to America). In order to keep the profits up, more and more merchants converted to the nascent religion of Industrialism, and began using machines manned by cheap, apprentice-level-or-lower labor to produce shoddy, inferior goods to undercut the traditionally sacred arrangements of pricing wholesalers had with the craftsmen. A folksong written during the time gives some indication of what the effect this proto-borgification was having on real, live people:

Still your debts and taxes want pay’d

Coined of the poor and dead

Your Orders and French wars hurt trade

And weavers cry out for breadShe bends no more to her poor lot

A life of nowt but toil

Enriching the mighty and great

While her own flowers spoilShe cries aloud her hero’s name

Her Sherwood hero Ludd

Will set a stop to wars and steam

And wages as they stood[Before 23 June] 1812 Poem, “The Tintwhistle Weaver’s Daughter”

Having unilaterally dissolved his ancient bonds of trust with the artisans, the newly-minted industrialist, whether his power looms were driven by waterwheels or steam, applied the newly-written – Wealth of Nations was published only 3 years before Ned Ludd’s rage against the machine – gospel of progress, the Free Market (peace and blessing be upon it), against those with whom he had had a deal. In their worldview, profits took precedence over human lives or general economic health; Luddites reacted by counting the number of souls any given machine was replacing. In March, 1811, they took things a few steps further when they started sending letters to employers in Nottingham – and listing the sender as “Ned Ludd and the Army of Redressers.”

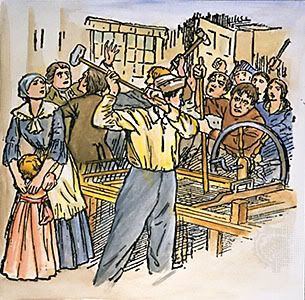

For about a month prior to the night of March 11th, the textile workers of the Midlands had been engaged in nighttime acts of outrage-based resistance – stealing critical machine components, that sort of thing – and indeed, their gathering earlier that day near the Exchange Hall in Nottinghamshire had been peaceful. As they proceeded home through the town of Arnold that evening, however, they got themselves riled up over issues of shoddy workmanship, wage reductions, and the use of “colt” laborers (those who hadn’t completed a formal, 7-year apprenticeship), broke into a shop containing wide knitting frames, and trashed the equipment. They also used the name “Ned Ludd” in connection with their movement for the first time.

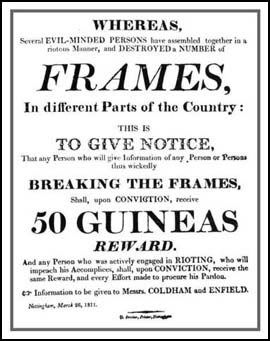

Nightly attacks followed for the next month or so; despite a £50 reward offered by the Prince Regent for “giving information on any person or persons wickedly breaking the frames”, not a single frame-breaker was placed under arrest. Their rage vented, the Luddites laid low for the summer – some reports have them organizing on the moors or in the forest at night, drilling and practicing military maneuvers – but when a bad harvest promised another starvation-laced winter, they started vandalizing again. By mid-November, the Home Office was being inundated with reports of burning haystacks and of “2000 men, many of them armed, (who) were riotously traversing the County of Nottingham.” Negotiations in December between the knitters and their employers broke down, and as a result, so did more frames.

Nightly attacks followed for the next month or so; despite a £50 reward offered by the Prince Regent for “giving information on any person or persons wickedly breaking the frames”, not a single frame-breaker was placed under arrest. Their rage vented, the Luddites laid low for the summer – some reports have them organizing on the moors or in the forest at night, drilling and practicing military maneuvers – but when a bad harvest promised another starvation-laced winter, they started vandalizing again. By mid-November, the Home Office was being inundated with reports of burning haystacks and of “2000 men, many of them armed, (who) were riotously traversing the County of Nottingham.” Negotiations in December between the knitters and their employers broke down, and as a result, so did more frames.

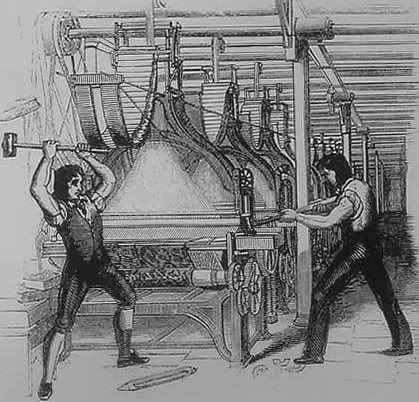

1812 was a downright momentous year: while Napoleon marched his army toward its doom at Borodino and beyond, the United States picked a fight with the biggest kid on the schoolyard. To President Madison, the time must’ve looked as ripe as it ever would for a little pre-emptive defense – the Brits were not only bogged down in a slugfest with Napoleon’s troops in Spain, but were also contending with the social upheaval that attended the spread of Luddism. By January, cotton-industry workers were trashing steam-powered stuff in Manchester, and in Yorkshire, a small and highly skilled group of “croppers,” who used 50-pound hand shears to crop the fuzz off the top of nearly-marketable fabric, started breaking new “shearing frames” that did a far crappier, far cheaper job than they ever would.

By the end of February, Parliament was debating whether or not to make frame-breaking a capital offense. The debates surrounding the enactment of the aptly-titled Frame-Breaking Bill are interesting – they represent a serious debate over the role of government, with the role of Devil’s Advocate (that is, the side that favored not killing a person because he had destroyed an inanimate object) being played by none other than Lord Byron his romantic self, then brand-new to his seat in the House of Lords. An analysis of the debates can be found here; spartacus provides an excerpt of what the young Lord Byron had to say (emphasis added):

During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the county I was informed that forty Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection.

Such was the state of that county, and such I have reason to believe it to be at this moment. But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community.

They were not ashamed to beg, but there was none to relieve them: their own means of subsistence were cut off, all other employment preoccupied; and their excesses, however to be deplored and condemned, can hardly be subject to surprise.

As the sword is the worst argument than can be used, so should it be the last. In this instance it has been the first; but providentially as yet only in the scabbard. The present measure will, indeed, pluck it from the sheath; yet had proper meetings been held in the earlier stages of these riots, had the grievances of these men and their masters (for they also had their grievances) been fairly weighed and justly examined, I do think that means might have been devised to restore these workmen to their avocations, and tranquility to the country.

Despite opposition from Byron and other would-be reformers, the Frame-Breaking Bill passed with an overwhelming majority and gained royal assent on March 20. It was re-enacted in 1814 with the downgraded penalty of transportation to Australia, but the death penalty was reinstated in yet another version, in 1817.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Though it wasn’t Luddite-related, Prime Minister Perceval met his untimely end in the Spring of 1812, when he became the only British PM to be assassinated. He was in the lobby of the House of Commons when a man named John Bellingham shot him at point-blank range. He explained his reasons why before the court in London a few days later:

Finding myself thus bereft of all hopes of redress, my affairs ruined by my long imprisonment in Russia through the fault of the British minister, my property all dispersed for want of my own attention, my family driven into tribulation and want, my wife and child claiming support, which I was unable to give them, myself involved in difficulties, and pressed on all sides by claims I could not answer; and that justice refused to me which is the duty of government to give, not as a matter of favour, but of right; and Mr. Perceval obstinately refusing to sanction my claims in Parliament; and I trust this fatal catastrophe will be warning to other ministers. If they had listened to my case this court would not have been engaged in this case, but Mr. Perceval obstinately refusing to sanction my claim in Parliament I was driven to despair, and under these agonizing feelings I was impelled to that desperate alternative which I unfortunately adopted.

The Ante Having Been Upped…

With 12,000 troops surging into the Midlands to deal with the Luddite crisis (Wikipedia makes the un-cited assertion that at one point during the uprising, there were more redcoats fighting Englishmen in England than there were fighting the French in Spain), and skyrocketing wheat prices in the marketplace, the Luddites had few options but to either surrender or attack. They chose the latter, organizing themselves into a guerilla army which taught itself how to march, drill, and form battle lines. It was also an army with a code of honor: fair warning was given before attacks, at least in those earliest days, even if the names on the return addresses had been changed in order to protect the (less than) innocent:

24 April 1812 letter from “Mr Twist” to “Mssrs McConnell & Kennady,” Manchester

A copy of another letter to McConnel and Kennedy, in William Hay’s handwriting, addresses the issue of the employment of women in the spinning factories–again, without much malice or menace toward McConnel and Kennedy. “Twist” is a type of cotton thread spun by McConnel, Kennedy and Company.

Mssrs McConnell & Kennady

Henry Street

Cotton Spinners

ManchesterSirs,

This is intented with greatest respect to give you notice that your men is employing girl’s at spinning-it is against law and equite equity and this is to ask you direct your men to employ men at wages enough for bread as their family’s are starveing and the manufactureing is depresst beneath their abilities to meet with the necessarie’s of life.Your respectfull servant

Mr Twist

Lud’s Boroughreeve

Aprill 24 1812

The letter likely caused the Kennedys great concern, for they no doubt had heard about what happened at Rawfolds Mill (halfway between Huddleston and Leeds) two weeks before. There, a heavily-armed group of over 100 Luddites attacked a mill whose owner, Charles Cartwright, had hired even better-armed mercenaries. According to a contemporary newspaper report:

The sentinel at the mill observed several signals that were supposed to indicate an approaching attack, through both that and the following night passed over without molestation. On Saturday night (April 11), about half-past twelve, there was a firing heard from the north which was answered from the south, and again from west to east; this firing was accompanied by other signals and in a few minutes a number of armed men surprised the two sentinels without the mill, and having secured both their arms and their persons, made a violent attack upon the mill, broke in the window frames, and discharged a volley into the premises at the same instant.

Roused by this assault, the guard within the mill flew to arms, and discharged a heavy fire of musketry upon the assailants; this fire was returned and repeated without intermission during the conflict, the men attempting all the time to force an entrance, but without success, a number of voices crying continually “Bank up!” “Murder them!” “Pull down the door!” and mixing these exclamations with the most horrid imprecations.

Again and again the attempts to make a breach were repeated, with a firmness and consistency worthy a better cause; but every renewed attempt ended in disappointment, while the flashes from the fire-arms of the insurgents served to direct the guards to their aim. For about 90 minutes this engagement continued with undiminished fury, till at length, finding all their efforts to enter the mill fruitless, the firing and hammering without began to abate and soon after the whole body of the assailants retreated with precipitation, leaving on the field such of their wounded as could not join in the retreat.

Two of the wounded attackers left on the field were retrieved by elements of the British Army sent to reinforce the Blackwater types, but later died of their injuries; the mill’s defenders reported no casualties, but did marvel at the number of bullet-sized perforations in the walls. Not surprisingly, things grew very tense around Huddleston over the next couple of weeks, as The Man redoubled his efforts to recruit snitches and agents provocateur. On April 28, a mill owner (and confirmed Luddite-hater) named William Horsfall was ambushed and shot as he made his way home. Less than a year later, three men – George Mellor, William Thorpe, and Thomas Smith – were hanged for the crime.

General Ludd Gets Violent

The attack on Rawfolds Mill and the murder of William Horsfall were not isolated incidents: by mid-April, violence was raging throughout the Midlands. On the 20th, several thousand men, using the distraction of a large food riot in Manchester as cover, attacked a mill owned by Emanuel Burton – who, it turned out, was also hiring armed guards to protect his machines. Three Luddites were killed that day; on the next, when the Luddites again attacked Burton’s Mill and were repulsed, the mob torched Burton’s house. They saw seven more of their number fall as the Army arrived on the scene with muskets blazing.

On the 23rd, Wray & Duncroff’s Mill in Westhoughton was burned, resulting in the arrest of 12 suspects, four of whom were later executed. One of these was a 12-year-old boy who cried out for his mother from the gallows; later investigation by a proto-muckraker named John Edward Taylor found that the attack was likely due to the efforts of agents provocateur in the employ of one Colonel Fletcher, a Manchester magistrate.

Infiltration by spies and other such rats was a constant problem for the Luddites, since the price of a man’s honor tends to drop as he watches his family starve. The public doesn’t always back the work of a snitch, though: after the Deputy Constable of Manchester arrived at a meeting of weavers in June, 1812, and arrested 38 people, he was unable to secure the conviction of a single one before a jury of their peers. Trials continued through 1812 and into 1813 – 8 sentenced to death and 13 transported to Australia in Lancashire, 15 executed in York, etc. – but these were less of a deterrent to would-be Luddites than carrot-and-stick approach of granting royal pardons conditioned on the swearing of loyalty oaths.

In some areas, the Luddites won small wage, usage, and price concessions, but by 1813, the movement had pretty much run its course. Frame-breaking resurfaced in 1814 and 1817, yet while “Ned Ludd” still wrote a few threatening letters every now again, his followers moved on to other explorations of the sociopolitical territory they had opened up – historioranters E. P. Thompson and Barbara Hammond both assert that Luddism was in important step in the formation of class consciousness and labor unions in Great Britain. It’s likely, for example, that the leader of the failed Pentrich Uprising in 1817 (being an unemployed stockinger from Nottingham) was an ex-Luddite, and the Swing Riots in 1830-32, with their trashing of threshing machines, show sure signs of Luddite influence.

There are certainly other views of Luddism: Clay Shirky, in a July, 2007 article entitled Andrew Keen: Rescuing ‘Luddite’ from the Luddites puts forth an argument that the Luddites were simply anti-technological brutes who despised consumers. In that narrow-minded perspective so often found in the dank recesses of the supply-sider mind and in business schools – where a crappily-constructed widget is, for all intents and purposes, regarded as identical to a widget crafted by the hand of an artisan – he reaches the conclusion that

…What the Luddites were rioting in favor of was price gouging; they didn’t care how much a wide-frame loom might save in production costs, so long as none of those savings were passed on to their fellow citizens.

Their common cause was not with citizens and against industrialists, it was against citizens and with those industrialists who joined them in a cartel. The effect of their campaign, had it succeeded, would been to have raise, rather than lower, the profits of the wide-frame operators, while producing no benefit for those consumers who used cloth in their daily lives, which is to say the entire population of England.

Personally, I don’t believe the Luddites were colluding against the general citizenry of England (neither did most of the commenters who responded to Mr. Shirky’s blog), any more than someone who drives away from a gas pump without paying is part of a scheme to line the pockets of oil execs. Rather, Luddism, as I noted at the outset of this essay, was the product of complex set of socioeconomic and sociopolitical pressures – definitely not a simplistic, technophobic response to modernity, nor a plot to advance the cause of the price-gouger.

Historiorant

The fact that Ted Stevens (R-Alaska, in case you’d forgotten) thinks the Web is a series of tubes crisscrossing the planet, or John McCain’s inability to use The Google without the assistance of his wife, or George Bush’s references to stuff going on on the Internets does not make them Luddites. We ought to be careful as to how we apply the term – rather than use it as a synonym for someone who pines for the days of vacuum tubes and car engines one could fix for oneself, we should think of the Luddites as the class warriors they were. The choices they made weren’t necessarily heroic, but they didn’t have many options from which to select a course of action – and when they did take the field of battle in the Class War, they (generally) comported themselves with a sense of integrity that was as lost on the frame-owners of yesteryear as it would be on the corporate tycoons of today.

The fact that Ted Stevens (R-Alaska, in case you’d forgotten) thinks the Web is a series of tubes crisscrossing the planet, or John McCain’s inability to use The Google without the assistance of his wife, or George Bush’s references to stuff going on on the Internets does not make them Luddites. We ought to be careful as to how we apply the term – rather than use it as a synonym for someone who pines for the days of vacuum tubes and car engines one could fix for oneself, we should think of the Luddites as the class warriors they were. The choices they made weren’t necessarily heroic, but they didn’t have many options from which to select a course of action – and when they did take the field of battle in the Class War, they (generally) comported themselves with a sense of integrity that was as lost on the frame-owners of yesteryear as it would be on the corporate tycoons of today.

In other Cave news, please keep a lookout for an upcoming fundraiser blogathon for fellow Kossack possum, who’s running – under his real-world name, Jerry Northington – for the At-Large House seat in the great state of Delaware. The primary is on the 9th, and things are looking positive for the good guys – if all goes as it should, we’re going to be trying to fill up Jerry’s war chest for the general election.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

and have allowed various distractions and stuff to keep me from completing one of these in a timely manner for a couple of weeks. I really am trying to be better… 🙁

…righteously distilled as I have come to expect. 🙂

This is a great essay. Thanks.

I’ll try to get her to give this a read as well. Currently she is busy…knitting, of course. 🙂

Looks like some good background for her women’s studies class. 🙂

At the risk of gushing, the Cave of the Moonbat is one of my favorite places, and it’s always a delight to be invited within.

Thanks!

and timely in a everything old is new way. The new/old robber barons have done it again, profit is king. People can just go screw themselves and after all it helps mankind as they get cheap shit.

I once fancied myself a Luddite. I was a graphic artist trained before the Mac took over all the jobs once preformed by various craftspeople. The question was posed to me by a colleague who informed me that computers were going to make my job redundant, High Tech or Low Tech? I went for low, and took up the age old art of pottery hand glazed in the Italian style of Majolica. That lasted about 5 years and then NAFTA flooded the market with both Chinese knock offs and beautiful Tunisian work. Not good for the artisans globally, were all slaves to the maximum profit of those who deal.

So I learned to use the computer, but I’m still a Luddite in the sense that I do not believe that progress is measured by profit alone or that each new labor saving device is a boon. I’m a ‘she who does person’ and each change technologically that touts itself as progress seems to seek to take labor of the human sort out of the equation, not to mention the environment and over consumption. Great history. Thanks Moonbat for history lesson. Over the years I have learned a lot reading your lessons.