(6 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

Disclaimer: Once again I beg your indulgence for posting a diary such as this during a time of momentous events. It is neither overtly political nor topical. It is however a true story of life in these United States and I offer it here for those of us who could use the diversion. With respect to topical matters I have only this to say: the ‘bailout deal’ is another Republican rip-off, hold the responsible accountable, and ensure that the American people are the primary beneficiaries of any deal. At this point I am inclined to say let there be no bailout at all. Let the market that the fat cats have worshiped be their master. That philosophical note being made, I think the chances of the American people getting what is best for them out of this situation are, regrettably, slim to none.

Foreward

There was an overwhelming response to Part I of this series. The community was very kind and I was deeply touched. Thank you all for that.

There were only a couple of comments that were perhaps less than kind – but they had their own merits I suppose. One person asked the name of the guy who was killed and asked if he was just a statistic to me. I thought it inappropriate to respond at the time, but after mulling it over I now think I should.

I’m not going to give his name. I still think that’s inappropriate, but I will tell you that he was a friend of mine and had been ever since we were in 7th grade together. He was a smart and funny kid and a fellow hippie. I never had a cross word with him and never wished him ill.

I do feel guilty though, both because my memory of the events is imperfect and because, at the very least, I did not keep it from happening. As people will in such circumstances, I have been over every possible permutation of the events that night. What if I had done this or said that? What if I had been elsewhere that night, doing something different? What if I had never taken that first snort of heroin?

But sadly enough, once a thing is done it can only be regretted. I will bear my regrets to the grave, and my friend who was killed that night will be with me every step of the way – just as he has been for these past 37 years.

The second questioner said I confessed to taking part in a murder and wanted to know what was so great about that. First of all, there is nothing great about any of it. It was a terrible tragedy for everyone involved – and remains so to this day. The guy who did the killing was a former mental patient and ex-con from out of state, things I only found out after the fact. Unlike the victim, I barely knew him. He’d only shown up in our town a couple of months prior. His death penalty was eventually commuted to life, and for some reason (no good reason I can assure you), they let him out. I make that parenthetical statement not because I don’t think that people can change and change dramatically – I know for a fact that they can and do. No, I say that only because I would occasionally get news about him on the prison grapevine (he was at a different unit), and none of it was good. I know that he was involved in armed robberies of other inmates and committed numerous acts of violence in prison. I was recently told that he has been dead for nearly 15 years. I don’t miss him at all. There is nothing I regret more than having ever met him in the first place. I was terrified of running into him the whole time I was in prison, for in my mind, and in my life he was the devil incarnate. As the only witness to what he’d done, I had testified against him at his trial and he had sworn to kill me for it. For the whole time I was in prison I was afraid he’d be the death of me.

As to the confession, that’s not exactly the story I meant to tell. While I came uncomfortably close to a murder (to say the very least), I was never a willing participant – and the murder was already over by the time I stumbled out of the bathroom and into the event that would change my life forever. It’s a subtle but important difference and a more nuanced tale to be sure. That’s one thing that makes it a hard story to tell. It was hard to explain to the jury as well, so you’re not the first who didn’t see it my way.

Look, I’m no angel and I’ve done a lot of questionable things – so I’m nobody’s role model and I have never held myself out as any sort of paragon of virtue or a picture of innocence. But if there are lessons to be learned from our mistakes, I have more than a few to pass along. I felt a duty to tell this story, or I never would have. It was not easy. It would be easier in some ways if I had killed him. Then I could just say I did this terrible thing – and I’m sorry. It’s harder to explain what really happened. All I can do is try…and so I have.

Judge me as you will, but remember this…being convicted of a crime doesn’t mean you did it. People are wrongfully convicted all the time. People find that hard to believe but it’s true. Imagine having your fate put into the hands of twelve more-or-less randomly chosen citizens on the heels of a mountain of confusing, conflicting, and emotionally charged testimony. Most criminal defense attorneys will tell you it’s a terrifying prospect. Our criminal justice system, in this way and in every other way, reeks to high heaven and rarely gets it right. Just ask ’em down at the Innocence Project, to whom I dedicate the following from Steve Earle:

In the comment thread to Part I – Words Are Like Poison, one of my friends said he’d like to see examples for my statement: I saw the very best and the very worst that we as a species have to offer.

I saw gratuitous acts of kindness, compassion and mercy. I saw enormous courage – often in defense of the defenseless. I saw the sheer durability of the human spirit despite our all too fragile nature. I saw how big a human heart can be.

On the other end of the scale I saw life cheaply valued, I saw moral weakness, personal betrayal, brutality, cruelty and torture.

All it takes to oppose torture is to be human, but it is especially painful to see prisoners tortured when you understand how helpless prisoners are. As a prisoner you can resist, raise hell or fight. You can make them sic the goon squad on you, beat you or turn the hose on you – and this they will happily do…but in the end, you are helpless. Having this knowledge deep in my bones is what makes me react so viscerally to the subject of the torture of helpless prisoners, and what makes me revere all who advance the cause of human kindness. I know how sweet and wondrous a simple act of human kindness can be to those in dire circumstances. I know that there is no more precious commodity in this world than compassion – it is what makes us human.

To be a little more specific about the best in us, take the case of my friend Phillip. Phillip was middle-aged, middleclass and straight as an arrow. He was in his forties when, in a fit of rage he struck his wife one night during an argument. It killed her. Phillip pled guilty and was given a life sentence. I was one of the first people Phillip met in the County Jail in our mutual hometown immediately following his arrest. He was a shattered man.

I don’t excuse, condone or minimize what Phillip did, but just want to point out that he had, by all accounts, never struck his wife before – there was no history of it and knowing him, I fully expect that it’s true. It was the sort of thing that happens often enough – a momentary lapse in judgment or self-control and the world changes dramatically and forever.

In a New York minute…everything can change.

But for that one brief moment, for that New York minute, my friend Phillip was, I am convinced, as innocent a man as I ever knew.

Phillip and I ended up at Draper together but were assigned to different cellblocks. I tried to help him but was limited by our separate cellblock assignments and by the fact that I was up to my ears in alligators with respect to my own survival. There was only so much I could do to help Phillip, but I did that as best I could.

Phillip was such an obvious square that it made him a target. I tried to make sure everyone knew that he had at least one friend who would stand up for him – but again, there were limits to what I could do. I was a nineteen-year-old fish myself and had my hands full. Phillip suffered a lot of abuse and intimidation. At one point he wanted to request Protective Custody. PC was where they put snitches or others who, for whatever reasons, can’t bear life with other convicts. It’s life in a single cell where you don’t have to deal with other inmates, but it makes you crazy after a while (seriously crazy) – and once you go to PC, you’ll play hell ever making it back to population.

Anyway, he stuck it out and at some point started teaching an illiterate inmate how to read. Over the years he became a one-man literacy program teaching dozens of illiterate inmates to read and becoming a well-respected man in the process. Two years into his sentence he had no worries with respect to other inmates – except of course for the usual stupid, crazy or unpredictable that everyone dealt with.

The fact that Phillip could pick up the pieces of his life, come to terms with the enormous challenges presented by his new circumstances, resist the lure of Protective Custody, face down his demons, do positive and unselfish things with his time and talents and come to be respected by a very tough crowd speaks to the richness, depth and resourcefulness of the human spirit.

Or take my friend Ray. Raised in a whorehouse in Mobile, he had crime in his DNA and tripped his way through the juvenile justice system landing inexorably in the adult system for robbery at the tender age of 16. Sending teenagers to adult prison is something the state of Alabama was bad to do – still is for all I know. There are few things crueler in my view than putting juveniles in adult prisons. I’m sure most would be shocked at how often it happens.

Ray was a few years older than me and had been in prison 7 or 8 years when I first met him shortly after my own arrival at Draper. We met on a common work assignment and seemed to hit it off. He was a rare intellect and about as well-read a man as I have ever known. He stood maybe 5’8′, and at 120 or so, was not a big guy. He wore thick glasses and looked young for his age. My initial impression was that of a mild-mannered, soft-spoken, bookish fellow…what we’d call a nerd these days I guess. You’d think he was a natural victim, but he seemed unafraid. I at first attributed that to how long he’d been in – amazingly enough, you do get used to it after a point.

I still didn’t know much about him other than that he was smart, well-read, and a hell of a chess player, when one day in a volleyball game I saw him lose his temper…just briefly. What I noticed about it was that he got really pissed really fast but just as quickly brought himself under control – and that the big dangerous hard guy he got mad at turned white as a sheet and had to go sit down.

Later that same day I was standing near the head of a long line waiting for the mess hall to open for the evening meal when Ray came walking down the hall and walked up to me and started a conversation. At some point I noticed that not only had no one threatened his life for bucking line, no one said a word. After a few minutes he left to go catch a few last moments on the exercise yard. As he moved thru the crowd, there was a visible parting of the waves as people moved to make room for him to pass. I began to wonder about my new friend.

About then the guy behind me in line said, “You friends with Ray ___?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“That’s a bad motherfucker,” he said.

“No shit?”

“Stone killer.”

So I began to ask anyone I trusted who might know and gradually began to piece together the story. Over the years that followed Ray himself filled in the blanks. We became good friends.

As a 16-year-old convict who looked 14, Ray had a hard way to go at Alabama’s Kilby prison circa 1964. On his first day in population he was assaulted by an older inmate and in the ensuing fight killed his attacker with a shank he’d purchased for protection. They put Ray in solitary…for a year.

To survive a year in solitary with your sanity intact requires a fierce effort. Sensing that to do nothing would be to rot, Ray began to invent ways to occupy himself. There was a library cart that came twice a week pushed by a convict assigned to the prison library. Ray always took 3 books, the official limit. He didn’t care what they were, western shoot-em-ups or British Romantic Poetry, he read anything and everything he could get his hands on. He read constantly, he learned to play chess by mail with members of a chess club in New York, and to communicate with other cons using tap code and kites. He exercised like a fiend and studied law by ordering law books from the library. A year in solitary is a hard lifetime but Ray made it, and they finally let him back into population.

It was no time before he was attacked again. The guy didn’t die this time but only because he was lucky. Ray went back to solitary. In this manner Ray spent most of his first four years in solitary confinement, reading, writing, exercising, growing, learning and surviving a harsh existence. Ray told me that he was so determined to survive that he found it within himself to inflict violence with calm determination…which is what made him so dangerous – thus the outsized reputation. He hurt quite a few people – but then they had all asked for it.

This was all behind him when I met Ray. He had finally gotten old enough and developed such a reputation for extreme violence that people quit attacking him. It all seemed so incongruous. I never saw him lose his temper but the one time, and I never saw him involved in any violence at all. For all the time I knew him, he was a perfect gentleman and a pleasant companion. I came to have great respect and depth of feeling for Ray and would have walked into the mouth of hell for him. Such a commitment was a serious matter in prison for you never knew when the opportunity might present itself. When someone tells you they have your back in prison, it’s meant literally and is a serious obligation, the implication being that it goes both ways. Prisoners understand the need for people to take care of each other.

Ray and I and a few other convicts worked together to help start Alabama’s first prison college program. We hooked up with some folks from a state Junior College who would supply the teachers, wrote a grant proposal, got federal funding and we were off to the races. Ray graduated and was paroled a couple of years before me, but we stayed in touch and visited from time to time after I got out. Always brilliant, he went on to get a PhD and became a respected lecturer, teacher and consultant in the fields of Psychology and Corrections.

We were involved at the same university for a time that had a large Criminal Justice program. Ray and I were both recruited to team-teach courses involving criminology, corrections, penology, counseling, etc. We were each paired with a PhD and divided teaching duties with them. So the students would get both the academic view and the gritty reality – or the convict’s POV anyway. I think it provided the students some real insight and it was a lot of fun to do.

Ray and I got a kick out of seeing each other at some of the faculty soirees we both attended. Only Ray and I fully appreciated what a leap in reality we had each made – though our Criminology profs got it. We had emerged from the depths of hell on earth to enjoy tea and crumpets at the Dean’s house. It was nothing less than surreal.

Ray had crime in his DNA but he overcame it all. He defied all the odds. His story is about redemption. It is inspiration for those in hopeless circumstances and a cautionary tale for the rest of us that says we should be very careful about writing people off too easily. People can and do change, often in profound ways…people can and do overcome incredible odds. And in this life, you never know what’s going to happen next.

Part II – Wear Your Love Like Heaven

As a young hippie gypsy, there was very little that meant more to me than my personal freedom. It was an onerous thing to lose. Even harder was losing the love of my life, a wondrous and heavenly creature named Cheryl. I wrote about it in The Secret History of My Foolish Heart.

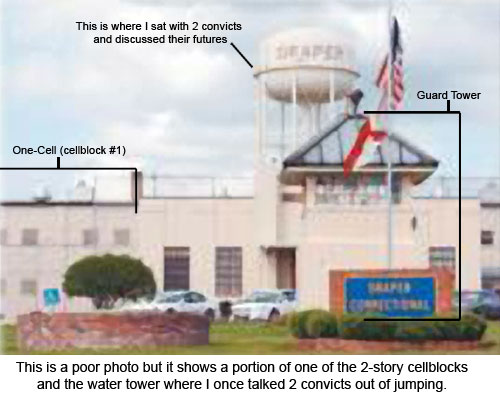

I’ve always had the strangest karma. The most bizarre things happen to me. The following is the kind of story that isn’t credible enough to work as fiction. Only real life can be this strange. I promised in Part I to tell the story of the two convicts I talked down from the water tower at Draper – so here goes. It is one of those stories that starts small but then grows into a separate and larger story all its own.

Following my release from prison I got into the prison reform business. As director of the Alabama Prison Project, I had a small office in the ACLU building in the state capitol of Montgomery. One morning as I returned to the office from running an errand, I was confronted by everyone in the office all yapping at me excitedly wanting to know if I’d been listening to the radio. I hadn’t but it seems they had been broadcasting on the local stations that state prison officials were looking for me. I was needed urgently at Draper prison, they were saying, where two inmates had climbed the water tower and were threatening to jump if they didn’t get to speak with me.

So I hopped in my trusty vintage land yacht, flipped on the emergency blinkers and screamed down the highway the 30 miles to Draper. I drove directly to the back gate, which was close to the tower. The place was jammed with officials and news teams. The prison spokesman was there, the Commissioner and the Deputy Commissioner of the Board of Corrections were there, all their minions and the warden and all his minions were there. They were all so relieved to see me. It was perfectly weird.

The prison spokesman and the Commissioner, both of whom I knew quite well, briefed me and all but begged me to provide a good outcome. I assured them I would do my best, and began the long climb up the tower. Arriving at the top I met the two who had caused all this commotion, a gentleman whose name I don’t recall and a young man I came to know as Little Dutch. I’d never met either of them before. They only knew me by reputation. Little Dutch was the guy with a beef. The other fellow was his friend who, being very nearly as hopeless, was just going along with the plan – even if it meant jumping to his death.

Little Dutch explained that he had a life sentence out of Phoenix City for a murder he had nothing to do with. I figured he was probably but not necessarily lying, but that it didn’t really matter at the moment. What mattered was getting these guys down off the water tower in one piece.

So we sat on the catwalk together, our feet dangling out into space as Little Dutch talked about the details of his case expressing great frustration at how the system had served him. I could not have been more sympathetic. I had seen the system screw more people than I could count. I had seen time and time again how casually they took the utter destruction of a life entrusted, as it were, to their care.

As the conversation evolved, I eventually obligated myself to look into Little Dutch’s case personally and to use my offices, such as they were, to try and shed some light on his circumstances. That, as it turned out, was enough to dissuade him from jumping. It also, unbeknownst to me at the time, marked the beginning of the end of my tenure as a prison reformer.

“Ok, I’m ready to go down,” he said starting to get to his feet.

“Hold on,” I said causing him to sit back down.

“Look at ’em down there,” I said. “You’ve got the Commissioner, the Deputy Commissioner and news teams from every television and radio station in Montgomery down there. Seems like it would be a waste to just go down now and say aw shucks, we’re sorry. Maybe we ought to see what we can get out of this situation.”

I could see that I had their undivided attention. So we conferred on what we might offer as their ‘demands’ and eventually narrowed it down to a short list.

“Y’all stay here ’til I wave you down,” I said as I began the long climb to the ground. Once on terra firma, I approached the prison officials who had all bunched up around the commissioner, and announced that I was to read the demands on camera, to which the commissioner agreed. So as the cameras rolled I read off the short list, which included better food, better medical and dental treatment throughout the state prison system, and increased opportunities for rehabilitation for all inmates – and a promise that both inmates would remain at Draper and not be punitively transferred.

There were at least two worse places to be in the Alabama prison system, Atmore and Holman. Atmore was filthy, overcrowded, and dangerous – and to top it all off they tried to work you to death in the cane fields.

Stretching for hundreds of acres in Escambia County is a vast plantation owned by the state. There are no stately mansions with white columns and verandas. There are, however, slave laborers. But the slave gangs, while mostly Black, are integrated. In the foggy dawn light they doubletime out to vegetable and cane fields, where they labor from “can-see to can’t-see” under the watchful eyes of shotgun-toting guards on horseback. If a slave should run, haying hounds will chase him down, and whether he returns dead or alive depends on the whim of his captor.

Some historians claim that Escambia County, Alabama, was the last county in the Confederacy to free its slaves. But it is now 1979, and “slave labor” administered by the state Department of Corrections is still the dominant form of labor relations in Escambia County, Alabama.

The name of the “slave quarters” was changed to G.K Fountain Correctional Center when the citizens of nearby Atmore demanded in 1974 that the name be changed to disassociate their town from the notorious Atmore prison. It was Atmore prison that Heywood Patterson in his autobiographical Scottsboro Boy described as “The Southernmost part of Hell.” Many say it still is, despite the name change.

At Draper they pretended that ‘rehabilitation’ was still a word, at Atmore they abandoned all pretense – at Holman they abandoned all hope.

Since it opened in the late 1960’s, Holman has had a reputation for being the most violent prison in the state. When I asked inmates to describe the place they used names like “The Slaughterhouse,” “Slaughter Pen of the South” and “House of Pain,” which all refer to the frequent stabbings that used to occur there. “The Bottom” and “The Pit” speak to its geographical location in the southernmost part of the state. As one inmate described it, in Alabama “you can’t get any lower than this.”

So keeping Little Dutch and his friend at Draper was important. Their actions would certainly earn them a punitive transfer into a deeper circle of hell without a promise to the contrary. The commissioner immediately agreed to all demands.

The final item on the list was that every news organization present had to verbally promise to follow up and make sure that all agreements were honored. This they did. Understanding full well that nothing was guaranteed, but feeling that I could at least hold the commissioner to the no punitive transfer promise, I waved the convicts down and that was that…all except for the unfolding story of Little Dutch.

Little Dutch had given me an address for his father in Phoenix City. I wrote him requesting information on his son’s case, and went about my Alabama Prison Project business trying to get people to give enough of a damn about their fellow human beings to try and improve conditions in Alabama’s godawful prisons. It was strictly up hill all the way. About the only ones who wanted to hear it were those who already gave a damn, and they were the precious few.

One day as I was going over some notes I had written for an anti-death penalty speech I was to give soon, I became aware of someone standing over me. I looked up to see a big square man, maybe 5′ 6″, four feet across the shoulders and a good 250, 300 pounds. He was built like a refrigerator and had a nose that you’ve seen before on boxers. He had ‘gangster’ written all over him.

“I’m Big Dutch,” he said in a deep gravelly voice. “Pleased ta meet cha.”

Under one arm he carried a tattered manila folder bulging with papers and xeroxed copies of documents and letters all related to his son’s case. I immediately surmised that these people were career criminals of the DNA variety, which I filed away for future reference. Still, being a criminal doesn’t exempt you from a right to justice. That’s what those civil rights, that we still had back then, were all about. The question wasn’t whether Little Dutch was a criminal but whether he was guilty of the crime for which he was serving a life sentence. The documents Big Dutch laid on my desk suggested that there was more than a little doubt about that.

This seems a likely place to bring Part II to a close. I will write about the case of Little Dutch Big Dutch, my near death experience with hitmen and my evening with Hunter S. Thompson in Part III.

P.S.

I almost forgot that I had also promised to tell a story that I believe had something to do with my receiving a pardon. I was granted a full pardon with complete restoration of civil rights in 1979 after only a year or less on parole. I would like to believe that the pardon was granted based upon the facts of my case, purely a matter of merit, and it may have been for all I know. But I have long been aware that pardons frequently have a political dimension and suspect that there may be one at the heart of my own. I may never know because it was never explained to me. I received it in the mail. It had nothing to do with my friendship with Don Siegelman (again, as far as I know) to answer a question that someone else had raised. I hadn’t known Don long then and he was just in the process of winning his first bid for office as Secretary of State. I think it had more to do with another matter. Here is the story to which I have often felt my pardon was connected.

I was out one night with an activist friend who was a community organizer (heh) with the American Friends Service Committee and one of our ACLU pals. I was driving as we returned to Montgomery from a trip into the countryside when a maniac came roaring up behind us on a deserted country road. He was clearly drunk and weaving all over the road so I pulled over to get out of his way and let him pass.

A little further down the road as we neared the outskirts of Montgomery we topped a rise to see a man down in the road. I pulled over immediately and ran to the scene. There were two cars on the side of the road, a man down, a woman (his wife) screaming hysterically and people beginning to emerge from nearby homes. The guy’s head was bleeding badly and he was semi-conscious and struggling to get up. I held him down as gently as I could and begged him not to move for fear he would injure himself further. He kept trying to get up, he was very strong, an off-duty policeman as it turned out. I laid down on him to keep him immobile, holding the top of his skull on with my hands while trying to address onlookers. Yes, an ambulance had been called. Yes, the police were on their way. Did anyone know of a nearby doctor? I’m a nurse someone in the crowd said. She knelt down and began to examine the man. You’re doing the right thing she told me as I continued to struggle with the injured man who wanted up. I spoke into his ear, “You’re going to be ok, just be calm, you’ve been injured, you must be still, please don’t move.” It seemed to take forever but finally an ambulance arrived and the paramedics took over.

We were told what hospital he had been taken to and we went there and kept vigil with his family and police friends as doctors struggled to save his life. In the end he succumbed to his injuries leaving a wife and two young children. They had all been out together as a family when they saw some teenagers playing Chinese fire drill. The off-duty cop flagged them down, got out of his car and was giving the teenagers a good talking to when the drunk topped the rise on the wrong side of the road and struck him. His children had been in the car the whole time.

The Montgomery Advertiser called me the next day and asked me to come in for an interview. I did so and was photographed. The next day’s paper ran a huge picture of me on the front page under the headline, Ex-Con Comes to Aid of Downed Officer.

I called the commissioner of the Board of Corrections later that day on an unrelated matter, telling him I needed a favor. “I can’t get your face off the front page of the paper,” he laughed.

Anyway, about a week later I received a pardon in the mail. It might have simply been a coincidence of timing. I don’t know.

Action Links:

American Civil Liberties Union

Amnesty International USA – Death Penalty

Allow me to close with a little ditty by Bob Dylan and friends called I Shall Be Released:

31 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

and long over-due prison reform.

…because I’ve been anxiously awaiting this. I’ll post again after.

always♥~

Just as the walls keep the prisoners in, they also keep the citizens out. So those on the outside don’t really get to know what’s going on in their names inside. That’s why essays like this one are so vitally important: getting imprisoned doesn’t end one’s humanity. It just makes it harder for the people on the outside to see it through the walls.

Thanks again for two, special, courageous essays. They both remind me of the wonderful stories written by my friend Jarvis Jay Masters, who’s still in San Quentin, still waiting for a decision on his appeal. But that’s an entire, other essay.

Author

Thanks for reading everyone.

…stunning, compelling, true and beautiful.

Just damn.

It could not be written any better. Having been in the system myself, many of the things you write of, are things I think of.

Thanks

You are one special, wonderful person. I think all of us here are lucky to “know” you. 🙂

… is a strange mix. One of the new things about online publishing, I guess. You dealt with the feedback from Part I and then your story in part unfolds as interaction with those who commented in your essay/diary both here and at the Orange.

It kind of boggles the mind! This is really a new art form.

As for your story, reading it makes me feel more in solidarity with you, if that makes any sense.

Oh — and reading this amid the present political circus is also a trip and a half.

Thanks, OPOL.

This is so interesting and profound – I’m awestruck once again. Thanks and praise to you for posting this OPOL. Can’t wait for Part 3!

to tell this story. i am so glad that you have come through it somehow with your tenderness intact. a lesser person woud have emerged bitter and angry. your understanding and resolve is extraordinary. we are fortunate that you can write about it so well. thank you for sharing.

Sometimes the razor wire is invisible except when the light shines on it just right.

…and so, fwiw, I can only offer a poem from my soul long ago, which I had not thought of in many years, but your writing brought it back.

I hope you will make these your writings into a book.

. . . always leave me sort of wondering where I’ve been all my life, or why nothing ever happens to me! Nothing very dramatic, anyway. I can’t exactly say I’d wish to trade places with you. But I salute your courage and your strength.

You and I share many experiences, at least in kind, if not in degree (mine pale in comparison).

Once, after sharing part of my story, folks said how remarkable it was, how tough, resilient and determined I had been to get through it. What I replied to them is, I’m guessing, much like you feel about yourself and your experiences.

“I’ve never felt like I was a ‘tough’ guy. You do something stupid, you get knocked down, you get back up and try something else. What else can a person do?”

Keep on, keeping on, dear friend!

Peace.

thanks for this, OPOL.