When future historioranters analyze the data from this past election, at least one thing will be abundantly clear: of all the nations in Africa, Kenya played the largest role in America’s 2008 electoral process. It hadn’t been expected to be so – the odds were on perennial favorites like Egypt, South Africa, the still un-interdicted Sudanese Genocide, or that nutjob in Zimbabwe – but there Kenya was, looming like Kilimanjaro over the Serengeti. Anyone that’s ever been on Serengeti Safaris from Tanzania Odyssey will know the immense feeling of being right in the heart of the Serengeti. And I mean over all the Serengeti: not only does the President-Elect have a close connection with the nation – Sarah Palin’s Witch Doctor is Kenyan by birth.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll contemplate a land that’s seen everything from the Dawn of Humanity to becostumed imperialists to a sad-but-all-too-typical history of governance since the Era of Decolonization. Maybe along the way, we’ll come to know a little more about the most famous Kenyan-American of all – a guy who even now seems to be operating by that old African proverb, “Just because he harmed your goat, do not go out and kill his bull.”

Geogrababble

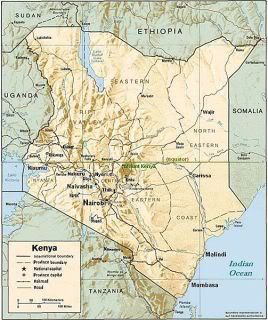

Enthusiasts of both absolute and relative location will find something to love about Kenya. For the absolutists, you just can’t beat 569,250 km² (353,715 mi²) that literally straddles the Equator – especially give that the nation’s highest point, Mount Kenya, at 5199 m (17,057 ft), is less than one degree south of the magic line. More relative types will want to know that Kenya enjoys/endures borders with several of the highest-name-recognition countries in all of Africa (which is in fact, Ms. Palin, a continent): it shares land frontiers with Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan – part of this one is disputed – Uganda, and Tanzania. Lake Victoria forms part of Kenya’s southwestern boundaries; the Indian Ocean (Kenya has 536 kilometers of trade-conducive coastline) washes the shores of the southeast.

Climactically speaking, Kenya ranges from tropical (along the coast) to arid (northern borders), with a host of other biomes in between. Low plains in the east rise to central highlands; a fertile plateau, bisected by the Great Rift Valley, dominates the west. Intensive agriculture occurs in the volcanic soil of the lower slopes of Mount Kenya, while higher up, vegetation transitions with altitude through dry upland forest to a wet, verdant montane to bamboo to lichens to chaparral to the truly weird:

…before arriving at the sparsely-vegetated alpine region around the summits. These are the eroding necks of a stand-alone shield volcano that last erupted between 2.6 and 3.1 million years ago – recent enough to have been seen by our most distant ancestors, who were even then evolving around the Great Rift Valley to the west.

Palinites, Please Skip This Section to Avoid Exposure to Empiricism

Your resident historiorantologist has gone to the “humans have been living in this place since before recorded time”-well more than once – earlier diaries have included reports on Afghanistan, Lebanon, Libya, and Persia – but as far as occupation by humanoid life forms goes, not many places have a history as old as Kenya’s. And not just primate-style life – a 2004 dig in a gorge near Lake Turkana unearthed a Mesozoic Era (200 million years ago) skull of a Giant Crocodile, proving that enough things lived in the shallow seas of the area to provide sustenance for a 40-foot fish/lizard whose jaws were six feet long and could exert a pressure of 18,000 pounds per foot.

Humankind walked erect in the same region around 198,000,000 years later, when Homo habilis (ca 2.5-1.8 million years ago) and Homo erectus (1.8 million-35,000 years ago) traipsed about, using tools and grokking fire. Among the most important of all paleoanthropological finds in Kenya was that of Turkana Boy, a 1.6 million-year-old Homo ergaster, near Lake Turkana in 1984. Noted for its size – five feet and growing, at a time when the conventional wisdom held that hominids were still chimp-sized – and the completeness of is skeleton, Turkana Boy today influences even left wing blogging – many reading this are no doubt familiar with the Turkana whose writings now grace the front page at The Left Coaster, and whose screen name was derived from that of this ancient ancestor.

Weird Historical Sidenote: Of course, the most famous name associated with archaeological digs in Kenya is that of Louis Leakey, his wife Mary, and their son, Richard. Louis, born in 1903 near Nairobi, grew up speaking tribal languages in Kenya before starting an academic career at Cambridge. His work focused on early hominids, a passion he’d held since his early teens years, but another passion, philandering, combined with a disastrous peer review in the mid-1930s, cost him both his career and his first wife. He married Mary and resurrected his academic standing by taking on the role of honorary curator of Coryndon Museum (later the Kenya National Museum) in 1941 and organizing the first Pan-African Congress of Prehistory in 1947.

By the 1950s, he and Mary were digging in spots from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania, then called Tanganyika) all the way up the Rift Valley through Kenya and Ethiopia. Disagreements with his son over personal matters and whether or not australopithecines were related to modern man’s Homo ancestors led to a falling out that was resolved only a few days before the elder Leakey passed away in 1972. Mary, who, though uncredentialed by academia, was a more meticulous (and probably a better) scientist than Louis, continued her work in Olduvai Gorge even as her husband womanized and took on widely divergent, occasionally-silly projects (though some, like the dispatching of Goodall, Fossey, and Galdikas to live with the apes, were brilliant). Mary died in 1996, and Richard went on to become involved in Kenyan politics – more on that below.

If an Army Marches on its Stomach, then a Tribe Migrates on its Tongue

The debate rages as to when honest-to-goodness Homo sapiens first migrated into the region that now comprises Kenya, but most sources seem to agree that the first people to settle there were Cushitic-speaking peoples who came from Ethiopia into northern and northeastern Kenya. It’s tough to pinpoint exactly when this might have occurred; the Cushites were nomadic, and the materials of their daily life (dried gourds for drinking, clothes made of natural fibers and animal products) were the sort of thing that decompose without leaving much of a trace – especially if you’re talking about a campsite that might’ve been used as early as 7000 BCE. In all likelihood, the Cushite migration – which is the sort of thing that has to be tracked ethnolinguistically – took place much later, beginning around 2000 BCE, but the point about the difficulty of obtaining evidence remains the same.

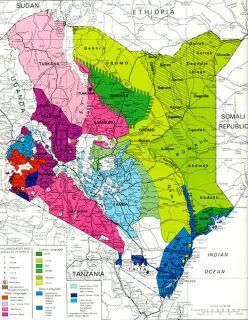

Cushite-speakers had Kenya to themselves long enough to develop four distinct geographical branches (at least, as far as can be told by making educated guesses about root languages), though today they are dominant only in the arid east and in pockets in the south. This is reflective of a pattern common in sub-Saharan Africa: tribes wax, wane, and sometimes disappear entirely as a result of the migrations of other tribes. So it was with the earlier Cushites – some were assimilated by the Nilotic-speaking Masai, others moved further south, into Tanzania, still others were pushed onto marginal land by more powerful or numerous newcomers.

The history of interaction between various migrating groups over the course of millennia has led to a patchwork of over 40 linguistically-linked tribes divided into three major groups:

- Bantu: including the politically-powerful Kikuyu and the agriculturalist Meru (who had a democratic form of government long before the era of colonization). Bantu-speakers form about three quarters of Kenya’s population today.

- Nilotic: including the Masai, famed for their nomadic herding lifestyle and aggressive style of livestock-ownership-expansion, and the Luo, of which Barack Obama’s father was a member.

- Cushitic: including a small portion of the Somali tribe, most of whose 25 million members live in Somalia, and the semi-nomadic, camel-herding Rendille of the Kaisut Desert.

These are only a handful of the tribes that populate Kenya today – descriptions of a great many more can be found through the links at Kenya-Advisor.com.

Free Trade by Any Other Name…

The tribes, many of which were fleeing the violence that accompanied empire-building in Egypt, Kush, or Aksum, carved out niches for themselves or suffered the consequences. The Luo, for example, came to dominate the shores of Lake Victoria, and have fought to maintain their control in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda ever since. The Mijikenda, a composite of 9 separate ethnic groups, live on a ridgeline in Kenya and Tanzania near the Indian Ocean coast. But it was those tribes who settled along the coast itself – the Swahili, especially – who reaped the benefits and the sorrows of being the first point of contact with the world outside Africa.

It’s debated as to whether or not the Swahili are a tribe made up of the descendants of any number of traders – African, Indian, Arab, Chinese, or Persian – who came to the islands off Kenya’s coast to trade for ivory, gold, and other African riches, or if they were, at some point in the past, a distinct biological entity. Regardless, it was people along the coast of Kenya who first came into contact with Arab traders, likely in the 8th century CE or before, giving rise to important trading towns like Malindi, Mombassa, Lamu, and Pate. Over time, the mix of people and cultures along the East African coast developed their own lingua franca: Swahili, a Bantu tongue with a large number of words borrowed from Arabic and other languages that have been spoken along the coast.

Though the Sultan of Zanzibar (an island off Tanzania) had opened his hall to Admiral Zheng He and his Chinese treasure fleet in the 1420s, Portuguese sailors were the first Europeans to make it to this part of Africa; the famed Vasco da Gama visited Mombassa on his way to “discovering” India in 1498. This did not bode well for the Arabs who had come to dominate the spice trade, as the entire purpose of Portugal’s adventures in the Indian Ocean centered on wresting control away from them. For Portugal, it was just business – Venice, established in the Middle East since the time of the Crusades, had a more-or-less exclusive European monopoly on the Arab-dominated spice trade, and King Manuel I and his people were looking to get a piece of the action.

To that end, Manuel created a viceregal post for Don Francisco de Almeida, and set him to the Indian Ocean with 22 ships, 1500 men, and orders to secure shipping lanes for Lisbon. This he did with murderous efficiency in 1505, capturing Kilwa off the southern coast of Tanzania, establishing a fort there, then heading north to Mombassa, where the local Moorish sultan was putting up a more of a fight. Mombassa fell only after heavy combat that saw the entire town of 10,000 put to the torch, and even this probably wouldn’t have been successful without Almeida’s implementing that old conquistador trick of enlisting the aid of the enemies of the conqueror’s enemies – in the case of Mombassa, Portuguese troops were augmented by those of the Sultan of Malindi. The treasures pillaged at Mombassa allowed Almeida to continue his conquests up the coast, as well as to later construct forts with which to protect harbors and shake down passersby. Mombassa itself was the site of Fort Jesus, constructed in 1593.

To that end, Manuel created a viceregal post for Don Francisco de Almeida, and set him to the Indian Ocean with 22 ships, 1500 men, and orders to secure shipping lanes for Lisbon. This he did with murderous efficiency in 1505, capturing Kilwa off the southern coast of Tanzania, establishing a fort there, then heading north to Mombassa, where the local Moorish sultan was putting up a more of a fight. Mombassa fell only after heavy combat that saw the entire town of 10,000 put to the torch, and even this probably wouldn’t have been successful without Almeida’s implementing that old conquistador trick of enlisting the aid of the enemies of the conqueror’s enemies – in the case of Mombassa, Portuguese troops were augmented by those of the Sultan of Malindi. The treasures pillaged at Mombassa allowed Almeida to continue his conquests up the coast, as well as to later construct forts with which to protect harbors and shake down passersby. Mombassa itself was the site of Fort Jesus, constructed in 1593.

A couple of decisive naval battles with the Arabs, Egyptians, and Indians proved that the Portuguese were in the Indian Ocean to stay – and that they did, for about a hundred years. They were challenged in 1585 and 1589 by the Ottoman Turks, and responded to rebelling Swahilis with a brutal crackdown that involved forcing Catholicism on a reluctant largely-Muslim population. By the late 1600s, the British and Dutch had supplanted the Portuguese as rulers of the oceans, Arabs from Oman were openly attacking their vessels and besieging their forts (Fort Jesus fell after a 33 month siege in 1698), and the spice trade in general had lost its profitability due to production in the Western Hemisphere; by 1730, the last Portuguese stronghold had fallen, leaving behind a legacy that can still be found in the Swahili language and in Kenya’s culture, architecture, and cuisine.

East African Scrambling

The Omani Arabs were the main colonizing force along the East African coast in the 1700s, creating clove plantations and puppet sultanates from Aden to Zanzibar. Sayyid Said bin Sultan (r. 1804-1856), in particular, was interested in expanding his power through trade in cloves and slaves; in 1832, he transferred his entire court from Oman to Zanzibar as a means of exerting greater control over his subject lands.

Said’s exploitation of the slave trade caused him to run afoul of the British, who were no longer as okay with human bondage as they’d once been – in 1822, they dispatched two warships and established a short-lived protectorate in Mombassa in response to appeals from local Swahili leaders seeking aid in resisting an Omani invasion. As the 19th century wore on, the Royal Navy incrementally clipped the power of the Omani sultans by interdicting the slave trade, but it wasn’t until the 1880s that the Great Colony Game really got underway between (in this case) Britain and Germany. Still, to this day some of the wealthiest and most powerful families on the coast trace their ancestry back to the Omani sheiks and sultans who colonized Kenya during this period.

The mid-19th century was the era for exploring the interior of Kenya. In the 1840s, a pair of German missionaries became the first Europeans to sight Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro; in the 1860s and 70s, David Livingstone mucked about the shores of Lake Victoria. Seeing the writing on the wall, the Sultan in Zanzibar offered the British East Africa Company a trading concession in 1877.

The Kaiser’s men showed up looking for their cut in 1885, when five warships steamed into Zanzibar and demanded the remainder of the Sultan’s mainland possessions. This precipitated a standoff between Britain and Germany (gunboat diplomacy wasn’t quite as effective now that telegraph cables had been laid everywhere), which ended with the British convincing their ostensible ally the Sultan to give up most of his territory to the Germans. A line, drawn at 1° South latitude to Lake Victoria, divided the German zone from the British, and still marks the Kenya/Tanzania border today. The Sultan was thus obligated to place millions of his subjects under British administration in exchange for guarantees of his own retention of power over a narrow strip of land along the coast through the offices of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, which officially remembered to leave a small bit of the remnants of the Sultan’s empire under his control.

In 1890, Germany declared that the kingdom of Buganda (modern Uganda) lay beyond the sphere of Britain’s influence, and so took it on as a protectorate. The whole affair could easily have devolved to open warfare, but London offered a compromise which Berlin surprisingly accepted: Germany would recognize British protectorates in Zanzibar, Uganda and Equatoria (the southern province of Sudan), in exchange for Britain handing over the apparently-useless island of Heligoland, which Britain had held since the Napoleonic Wars. Traditionally a tourist spot, spa, artist colony, and hideout for those on the wrong side of the Revolutions of 1830 and 1848, the importance of Heligoland was recognized by the German Naval Command, and it subsequently became a major naval base in both World Wars.

An unseemly fight between four competing entities – the local lord, Catholic missionaries who had built a cathedral out of reeds and sticks, Protestant missionaries who had just finished their own church, and the fort of the local Company official – each occupying one of the four hills that comprise Kampala, Uganda, in 1892 had an indirect impact on the history of Kenya. Though the Company guy won the four-way fight (he was the only one with a Maxim Gun), the Crown was worried enough that in 1894, it declares Buganda a Protectorate. Needing to ensure that Her Majesty’s new possession always had secure access to the sea, Victoria’s government declared Kenya a Protectorate the following year, compensating the East Africa Company with a £250,000 payoff.

An unseemly fight between four competing entities – the local lord, Catholic missionaries who had built a cathedral out of reeds and sticks, Protestant missionaries who had just finished their own church, and the fort of the local Company official – each occupying one of the four hills that comprise Kampala, Uganda, in 1892 had an indirect impact on the history of Kenya. Though the Company guy won the four-way fight (he was the only one with a Maxim Gun), the Crown was worried enough that in 1894, it declares Buganda a Protectorate. Needing to ensure that Her Majesty’s new possession always had secure access to the sea, Victoria’s government declared Kenya a Protectorate the following year, compensating the East Africa Company with a £250,000 payoff.

The White Highlands

In 1888, the British East Africa Company began its “economic development” program in Kenya and Uganda (then collectively known as British East Africa; Tanzania was known as German East Africa); by 1895, the area was named a protectorate and the imperialism began in earnest. Critical to the exploitation of the interior was the construction of a 956 km railroad from Mombassa to Kisumu (on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria; home of the Luo tribe and Barack Obama’s ancestors), for which a large number of skilled Indian construction workers were brought to Kenya.

Track-laying ground to a halt at the Tsavo River in 1898, when the project was plagued by a pair of man-eating lions which killed over 130 workers during a 9-month reign of terror. Faced with a workforce that was rapidly shrinking out of perfectly rational fear of being dismembered and consumed by gigantic cats, chief engineer Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson hunted The Ghost and the Darkness, as the lions were called; the proof of his success against them is now on display at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Offing the lions got the workers to come back, and the railroad was completed in 1901. British colonists and their Indian servants now came in large numbers to the interior, with settlement encouraged by generous land deals, the construction of the city of Nairobi, and a policy of dealing with troublesome tribes inspired by the American experience on the Great Plains. The Nandi tribe of the Great Rift Valley, who resisted the railway’s construction from 1895 to 1905, were forcibly confined to a “native reserve,” and this model was followed with later rebellious groups – or any that happened to live on desirable land in what became known as the White Highlands (interesting article from a 1959 Time magazine). Forced labor of the type formerly used in other African colonies was not outlawed until the 1920s, by which point the sizeable population of Indians, including Sikhs and Ismaili Muslims, were demanding a greater share of the colony’s political and economic life.

By the time they were settling the Kenyan highlands, the British were old hands at setting up colonies – they knew the value of favoring one tribe over another, of spreading animosity between native groups, and of establishing a legal code that placed themselves beyond the reach of indigenous reproach. In these ways, and through other capricious means (like drawing borders without consideration as to whose traditional territory is being bisected), the British were able to free themselves to more noble pursuits, such as introducing coffee agriculture or, as was the case with Danish aristocratic would-be farmer Karen Blixen, writing romance novels that become Robert Redford/Meryl Streep movies.

The African Take on the First World War

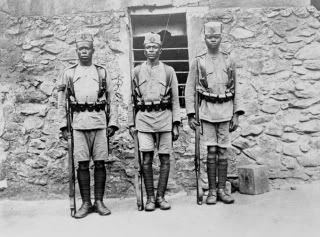

When the Great War broke out, all eyes – especially those belonging to Europeans – were fixated on the continent itself. In large part, the leaders of African colonies were left to their own devices, which led the German governor of East Africa to get with his British counterpart and announce the official neutrality of the two lands toward one another. For the German colonel in charge of the Kaiser’s forces in Tanganyika, however, this was a sidestepping of the Imperial will – if Germany was to be at war with Britain, then it should be so everywhere. Others in the German military agreed, which brought about the odd visit of the SMS Emden to Diego Garcia and convinced the aforementioned colonel, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, to disregard the governor’s directives and lead his 6000 or so German and Askari troops into one of the most successful guerilla campaign in military history.

When the Great War broke out, all eyes – especially those belonging to Europeans – were fixated on the continent itself. In large part, the leaders of African colonies were left to their own devices, which led the German governor of East Africa to get with his British counterpart and announce the official neutrality of the two lands toward one another. For the German colonel in charge of the Kaiser’s forces in Tanganyika, however, this was a sidestepping of the Imperial will – if Germany was to be at war with Britain, then it should be so everywhere. Others in the German military agreed, which brought about the odd visit of the SMS Emden to Diego Garcia and convinced the aforementioned colonel, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, to disregard the governor’s directives and lead his 6000 or so German and Askari troops into one of the most successful guerilla campaign in military history.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck began by successfully repelling an amphibious assault on the city of Tanga, near the border with British East Africa, in early November, 1914, then moved against the British railroads that kept the interior of the colonies supplied. He replenished his depleted stocks of guns and ammunition when his force captured a significant quantity of both at Jessin in January, 1915; these he supplemented with naval guns salvaged from a German cruiser and used as artillery. For the next three years, he directed raids on British forts, railways, and communications, obligating the British to commit tens of thousands of troops (who were much needed elsewhere) to deal with a commander whose pioneering techniques in waging guerilla war were proving distractingly effective.

Eventually, British numbers and ability to resupply wore down von Lettow-Vorbeck’s force, and he was engaged in a fighting retreat that took him as far south as Portuguese Mozambique. Here he captured a well-supplied fortress, and managed to hold out until the end of the war. Unlike virtually ever other commander of the First World War, he never lost a battle, achieved all the objectives that could have been expected of him, and was regarded by even as his foe as a courageous, and honorable warrior. He returned to Germany a hero, but quickly allied himself with rightist elements then warring in the streets for control of the Weimer Republic – von Lettow-Vorbeck led one of the Freikorps brigades that crushed the Spartacist revolt, but was forced to resign from the army in 1920, after supporting the failed Kapp Putsch. He was further ostracized when his attempt at forming a conservative opposition to Hitler in the early 30s failed; by the late 40s, he was in such dire straights that his old adversary, the British Afrikaner general Jan Christian Smuts set him up with a pension fund made up of donations from his former rivals.

The East Africa Campaign had unintended long-term effects on both sides. In Germany, one of von Lettow-Vorbeck’s junior officers went on to found and train the Brandenberger commando brigade, which saw much action as shock troops early in the Second World War. On the British side, the mobilization (read: forced conscription) of upwards of 400,000 Africans into the Carrier Corps resulted in increased politicization – that ole’ God-save-the-King spirit just wasn’t present in the diverse tribes that were basically enslaved in support of their colonial masters’ far-off conflicts. It also must be assumed that seeing armed Askari on the German side killing British and Indian soldiers had an impact, as well.

Colonial Idyll

Tea agriculture was introduced in the years after the Great War, coffee production expanded, and Kenya became known as a land of romance and Great White Hunters. In 1933, Ernest Hemingway stopped by to shoot things and write classic stories like The Snows of Kilimanjaro. It was also during this time that new, more challenging routes were being explored on the summits of Mount Kenya (first ascent was in 1899), and institutions like the Treetops Hotel were founded. Most of the African action in the Second World War took place far to the north of Kenya, and sub-Saharan colonies didn’t play as important a role as they had in the Great War.

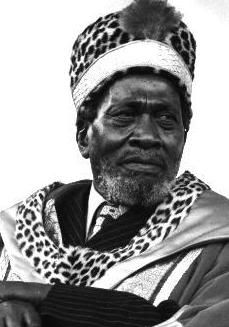

Not all was hunky-dory in the colony, however. Following the lead of the Indian community, which had demanded representation on the legislative council and turned up its nose at a lowball offer, the African community (or at least, the demographically-sizeable Kikuyu portion of it) formed the Young Kikuyu Association, a/k/a the East Africa Association, in 1921, to seek land reforms and greater African rights. The group was suppressed four years later, but in 1925 it members re-formed at the Kikuyu Central Association. In 1928, Jomo Kenyatta became the leader of the KCA, having established his cred via the land-reform newspaper Muigwithania and his meeting with Mahatma Gandhi, but he was labeled a communist by the British in the mid-1930s after speaking out against European-favoring land redistribution during a gold rush.

1952 was a significant year for several of the entities mentioned above. Elizabeth, the Duchess of York, was staying at the Treetops Hotel on the night her father. King George VI passed away – hence, that she “went to bed a princess, and woke up a queen.” It was also in 1952 that a political wing of the Kikuyu known as the Mau Mau rose up in rebellion against the status quo in general (and white settlers in particular), beginning with a broad-daylight spearing to death of a loyalist Kikuyu leader on October 7. Within two weeks, the British announced that they would be sending troops to deal with the insurrection; meanwhile, Kenyatta and several other prominent members of the nascent Kenyan nationalist movement were jailed, and would remain either imprisoned or under house arrest for the remainder of the decade.

1952 was a significant year for several of the entities mentioned above. Elizabeth, the Duchess of York, was staying at the Treetops Hotel on the night her father. King George VI passed away – hence, that she “went to bed a princess, and woke up a queen.” It was also in 1952 that a political wing of the Kikuyu known as the Mau Mau rose up in rebellion against the status quo in general (and white settlers in particular), beginning with a broad-daylight spearing to death of a loyalist Kikuyu leader on October 7. Within two weeks, the British announced that they would be sending troops to deal with the insurrection; meanwhile, Kenyatta and several other prominent members of the nascent Kenyan nationalist movement were jailed, and would remain either imprisoned or under house arrest for the remainder of the decade.

“A republic, if you can keep it.”

The suppression of the Mau Mau Rebellion took four years (though the state of emergency wasn’t lifted until December, 1959) and cost thousands of lives, as the scope of each side’s reprisals escalated. In the end, the Mau Mau killed far more Africans than they did Europeans, but the fear they evoked among white Kenyan settlers invited the Europeans to take actions they likely hastened the demise of the colonial power structure – by 1961, the government had yielded to pressure to hold free elections, allow for the formation of political parties, and release Kenyatta. He promptly assumed leadership of the new Kenya African National Union (KANU) and formed a less-moderate-than-the-British-had-hoped-for government when the nation was granted its independence on December 12, 1963.

The suppression of the Mau Mau Rebellion took four years (though the state of emergency wasn’t lifted until December, 1959) and cost thousands of lives, as the scope of each side’s reprisals escalated. In the end, the Mau Mau killed far more Africans than they did Europeans, but the fear they evoked among white Kenyan settlers invited the Europeans to take actions they likely hastened the demise of the colonial power structure – by 1961, the government had yielded to pressure to hold free elections, allow for the formation of political parties, and release Kenyatta. He promptly assumed leadership of the new Kenya African National Union (KANU) and formed a less-moderate-than-the-British-had-hoped-for government when the nation was granted its independence on December 12, 1963.

The new government was challenged from the outset by the Shifta, secessionist ethnic Somalis, who desired part of northeastern Kenya to join Somalia. The resulting Shifta War lasted until 1967, during which time the nation became increasingly a single-party state. In 1964, a new republican constitution was promulgated which made all political parties subservient to KANU. Opposition leaders like the Luo Oginga Odinga were jailed; a potential candidate for the presidency, Tom Mboya, was assassinated by a Kikuyu in 1969. Kenyatta was re-elected in 1974, and served through an increasingly-troubled time – Idi Amin was claiming huge tracts of Kenyan land for Uganda, for example – until his death in Mombassa in 1978. Though he was definitely a strongman dictator-type, Kenyatta never turned out to be the vengeful boogeyman the white Kenyans had feared; at the time of his death, Kenya was as stable and as prosperous as any nation in Africa, and a great deal moreso than most.

Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, Kenyatta’s vice-president, ascended to the presidency with the approval of parliament (he was of a minority Kalenjin tribe) and a slogan that went, “Follow the tracks!,” but once ensconced, he quickly set about ensuring that no one would be ascending behind him. Tribal societies were banned, universities were closed, and in June, 1982, the ruling KANU party officially declared Kenya a single-party state. Two months later, low-ranking members of the Air Force launched a coup attempt that failed, resulting in 12 death sentences, 900 suspects being jailed, and the essential dismemberment of the Kenyan Air Force.

Through all the repression, the Kenyan government was stepping up with regards to environmental laws. Laws protecting rhinos were advanced in the late seventies, and with world interest in Africa sparked by the 1985 release of Out of Africa, tough laws were passed against the ivory trade. Much of this move was spearheaded by paleontologist-cum-manager of the Department of Wildlife Richard Leakey, who was appointed the same year (1989) that President Moi publicly burned 12 tons of ivory in a strong statement against poaching.

Through all the repression, the Kenyan government was stepping up with regards to environmental laws. Laws protecting rhinos were advanced in the late seventies, and with world interest in Africa sparked by the 1985 release of Out of Africa, tough laws were passed against the ivory trade. Much of this move was spearheaded by paleontologist-cum-manager of the Department of Wildlife Richard Leakey, who was appointed the same year (1989) that President Moi publicly burned 12 tons of ivory in a strong statement against poaching.

The 1990s saw with the collapse of Cold War priorities the withdrawal of the props that held up dictators like Moi. Opposition parties began to form – Richard Leakey founded one, Safina, in 1995 – and without the substantial US aid he had enjoyed during the years of Soviet-American rivalry, Moi was increasingly forced to cede democratic ground. He remained in power through rigged elections in 1992, but the next year found austerity measures imposed upon Kenya by the IMF and World Bank lenders. This were also becoming more violent: Moi’s detractors (and/or their KANU agents provocateur) may or may not have been involved ethnic clashes along the coast in 1997. This fighting resulted in hundreds of deaths, as did al-Qaeda’s August, 1998, bombing of the US Embassy in Nairobi.

In 2001, Moi was obligated to form Kenya’s first-ever coalition government, and in 2002, constitutionally barred from seeking another term, he was forced to watch as Mwai Kibaki of the opposition National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) took the presidential oath. Kibaki soon announced free primary schooling for all Kenyan children and, more controversially, new safety rules pertaining to Matatu (privately-owned mini-bus taxis) owners. Prior to the Rise of Barack, Kenya’s most recent stint on the world stage came with the awarding of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, which went to Wangari Maathai, the Kenyan woman who was the brains behind the Green Belt movement.

Historiorant:

Nearly 40 million people live in Kenya – 36th in world population – but that number is so heavily impacted by the effects of AIDS that the CIA World Factbook contains a longish caveat about how excess mortality from the disease affects other demographic realms. This can be seen especially in the country’s median age: 18, with an overall life expectancy of 56. More than 1.2 million Kenyans are currently living with AIDS, while each year, 150,000 die (2003 estimate).

Nearly 40 million people live in Kenya – 36th in world population – but that number is so heavily impacted by the effects of AIDS that the CIA World Factbook contains a longish caveat about how excess mortality from the disease affects other demographic realms. This can be seen especially in the country’s median age: 18, with an overall life expectancy of 56. More than 1.2 million Kenyans are currently living with AIDS, while each year, 150,000 die (2003 estimate).

What will be the effect on Kenya of having a US president only one generation removed from Kisumu? I’d never be one to hazard a guess, but it will be an interesting dynamic to watch unfold – if the celebrations there on election night were any indication, this would be an ideal time for the United States and her rejuvenated European alliances to take great strides in righting the wrongs of our collective imperialist past.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

8 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

my list of countries that I absolutely have to visit grows longer.

🙂

…make newsletters or PowerPoints about Kenya. One of them was marathon champion and humanitarian Paul Tergat‘s godson. Bloomfield awarded Tergat an honorary degree 2004.

It’s always interesting to see countries through the eyes of people who grew up there.

But I hope you’re not judging the book Out of Africa by the movie. The book isn’t a romance novel, and the character who becomes Robert Redford in the movie is barely mentioned in the book.