( – promoted by buhdydharma )

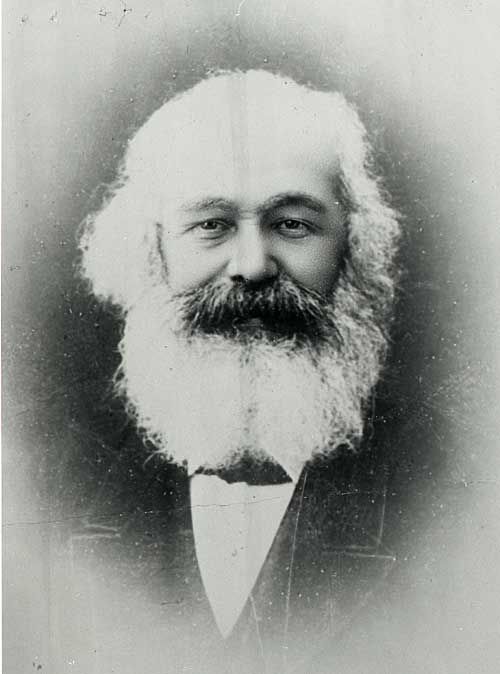

I’m getting these questions about Marx, again, over on Big Orange. “You’re against capitalism; are you some kind of marxist?” they ask. To me it doesn’t really matter: either I am a marxist or I’m not a marxist, depending on whether or not the gang affiliation of “being a marxist” means a lot to the person asking the question. But here’s a diary about old Moor, his chicken-scratchings, and his legacy.

OK, so this isn’t going to go away. I wrote a long diary on this last year, but I can see it’s time for another one.

(Reposted from Big Orange (and rewritten a bit) for the viewing pleasure of the Docudharma people)

OK, so your stock Republican association about Marx is that he was the father of Communism, that totalitarian evil which at last fell with the collapse of the Berlin Wall. We all know this is just more of the guilt-by-association tactic we hear and read from Republicans every day. If they mention Bert from Sesame Street in the same breath as Osama bin Laden, well then, Bert must be evil.

In fact, they tried to pull this garbage on Obama. GregMitch picked up on this back in April. I like “Trotsky The Horse”‘s response: You Call Him Socialist Like That’s A Bad Thing!

Most of my reluctance to discuss this stuff is because of the great nest of popular canards which have been spun about Marx and about socialism or communism. The generally Republican notion about all of this is that any form of sharing can be criticized as “socialism” if it’s the type of sharing they don’t like, i.e. sharing that is dependent upon “taxes” within a capitalist system. None of this has anything to do with Marx’s idea of socialism. That sort of complaint about “socialism” is about punishing poor people for being poor. Socialism means evil free lunch programs in the schools.

You see, Marx was all about suggesting that everyday business in the capitalist system was making the rich richer while everybody else just got by. His description of the capitalist world, as such, is even more correct today than it was when he was writing (in the 19th century). This is one main why the Republicans hate him so: truth makes their patrons look bad.

It’s also the origin of the standard canard about how “Marx wanted everyone to be equal.” He had no such ideas, and repudiated them in his “Critique of the Gotha Program.” Marx knew that people were not equal in talent, size, or intelligence; what he wanted to see was an end to social classes, an end to the society that (today) supports 1,125 billionaires while letting the bottom 40% of the human race live on less than $2/day. It takes a class system to make people THAT unequal. He suggested that the way to end social classes was not merely through redistribution, but through the creation of a solidarity among the world’s workers, such that sharing could eliminate class divisions. Thus his idea of socialism.

His idea of socialism, moreover, has an appeal which continues to this day. Republicans hate this idea more than anything in Marx, because it reveals the grasping emptiness in their inner beings.

As Ernest Mandel points out in a short piece on Marx:

Socialism is an economic system based upon conscious planning of production by associated producers (nowhere does Marx say: by the state), made possible by the abolition of private property of the means of production.

Yeah, we could use socialism right now. There are a couple of complex meanings in that complex sentence. “The abolition of private property of the means of production” means that there is a general commune around the stuff we use to produce the stuff we need, so that we all participate together in decisionmaking about it. Your personal property will still be yours under socialism. “Conscious planning of production by associated producers” means working people, operating democratically. It means we think before we produce: this is a necessary aspect of survival for the future.

What I am suggesting is that none of that nice stuff that A Siegel promotes in his numerous, wonderful diaries will do us any good against impending ecosystem crisis unless we have “socialism” (using this definition), too, because otherwise solar power etc. will simply supplement the drive to ecosystem ruination through “global warming,” habitat destruction, and other damages. We need socialism.

The canard that Marx’s version of socialism would provide no incentive for workers is often cited by ignoramuses who haven’t read Marx’s “Critique of the Gotha Program.” I’ve cited the purple passage in my earlier essay, down toward the bottom. Capitalist blowhards can go read that essay for themselves. Socialism would indeed be possible, if state repression combined with media propaganda did not continually inhibit it. And, of course, if the great majority of people were to want it. Socialism would, even from the “wealth” standpoint, be more free than capitalism. So much for Milton Friedman’s “free to choose.”

Marx’s goal of socialism has little to do with Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, or Kim Jong-Il. The whole appropriation of Marx by “communist states” was about the propaganda claim that these states made that “at least we’re working toward socialism.” When Che Guevara disputed the Soviet Union’s claim to be “working toward socialism” too many times, he was sent on a suicide mission to Bolivia. You just couldn’t do that sh*t in a Cuba dependent upon Soviet money. The proper answer was “yes Fidel, we are all working toward socialism.” When the Chinese had to “switch over” to the propaganda of capitalism, some time after Nixon went there in ’72, the government’s claim at that point was that socialism had been achieved. Uh-huh.

What really happened with Marx’s ideal was that it was appropriated by “contender states,” governments which wished to proclaim that they were “communist.” Kees van der Pijl discusses the idea of “contender states” in his books. The spread of capitalism around the world, van der Pijl suggests, created two state-society complexes:

1) The “Lockean heartland,” the states most directly responsible for propping up the capitalist system

2) The “contender states,” states outside of the “Lockean heartland” which wished to catch up with the “Lockean heartland” in capitalist development, usually through authoritarian forced-march construction projects.

Marx didn’t think very carefully about the effects of the spread of capitalism upon the international state system. He wanted the states to be taken over by working people and abolished: the “dictatorship of the proletariat” idea was the idea that there would be an ad-hoc administrative entity that would deal with the problems that would arise in the transition between capitalism and socialism. It wasn’t supposed to last very long. Instead, what the world got was seventy years of the Soviet Union and a few decades of the People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong. Neither of these regimes succeeded in being a “dictatorship of the proletariat”; both were merely contender states. Contender states, you see, need some form of strict discipline to catch up with the Lockean heartland: the “liberated” workers must push the “communist state” forward, if it is not to be taken over and parted out by capitalists. (Note that such an outcome actually happened when Boris Yeltsin took over Russia.)

Marx also did not think carefully about whether people would want socialism more than continued capitalism, as capitalism continued to take control over the world during his lifetime. For instance, Craig Calhoun argues in his classic The Question of Class Struggle that “from Marx’s day to the present, the conditions of revolutionary mobilization have been continually eroded in the advanced capitalist countries.” (239) Maybe the people who would otherwise want a revolution just want a better-paying job with benefits and decent working conditions, nowadays.

Both of these objections to Marx’s notion of socialism can be summed up with a single idea: capitalist discipline. It took later thinkers, most notably Michel Foucault, to dramatize the notion of capitalist discipline. Marx did not imagine, writing as he did so long ago, that he would need a theory to understand the forces which disciplined the bodies of workers so that they would accept capitalism as natural. In his time, you see, there was the Workingmen’s International. Nowadays you don’t even hear or read complaints about the Taft-Hartley Act.

Thus Marx underestimated the longevity of the capitalist system. The problem of capitalist discipline, and of how we can replace it with a form of discipline which will allow us to live in harmony with Earth’s ecosystems, is THE problem for our times. Most of my diaries are about that problem, and not the problem of class struggle.

OK, so that (and 330 other diaries written for DKos over the past three years) deals with Marx. That’s where I stand.

30 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

which proves for all Republicans that Bert is evil:

these guys have convinced most of us that keeping 70% of the wealth in the hands of 10% of Americans will somehow keep me solvent.

i just don’t get it.

also, i think it would be interesting to fuse the best ideas of socialism/capitalism/whateverism and see if there’s something workable there.

Yes well you know we only have free speech for those who support capitalism.

I always liked Gramsci myself. And the Canadian thinker Leo Panitch.

after I started commenting on dkos in 04? I was called a Marxist daily. The Libertarian contingency being the most likely to say been reading a lot of Marx lately? This was because I liked to quote Bob Dylan a lot. LOL. I have never read Marx other then the famous and accessible bits. I like this essay. You’ve stripped the hysteria of ideology, dogma and geopolitics from this and addressed the crux of the economic crisis we face today.

___________________________________________

I have been reading a lot of FDR lately, and was surprised to find that the economic depression of the thirties followed an environmental agricultural disaster. I also found a remarkable not often quoted speech, The Commonwealth Club Speech, from 1932. The inequities in our brand of capitalism were one of his worries even after the recovery. The crisis’s we face now are similar, the solution is the same IMHO

Every man has a right to life; and this means that he has also a right to make a comfortable living. He may by sloth or crime decline to exercise that right; but it may not be denied him. We have no actual famine or dearth; our industrial and agricultural mechanism can produce enough and to spare. Our government formal and informal, political and economic, owes to every one an avenue to possess himself of a portion of that plenty sufficient for his needs, through his own work.

Every man has a right to his own property, which means a right to be assured, to the fullest extent attainable, in the safety of his savings. By no other means can men carry the burdens of those parts of life which, in the nature of things, afford no chance of labor; childhood, sickness, old age. In all thought of property, this right is paramount; all other property rights must yield to it. If, in accord with this principle, we must restrict the operations of the speculator, the manipulator, even the financier, I believe we must accept the restriction as needful, not to hamper individualism but to protect it.

These two requirements must be satisfied, in the main, by the individuals who claim and hold control of the great industrial and financial combinations, which dominate so large a part of our industrial life. They have undertaken to be not businessmen, but princes — princes of property. I am not prepared to say that the system which produces them is wrong. I am very clear that they must fearlessly and competently assume the responsibility which goes with the power. So many enlightened businessmen know this that the statement would be little more than a platitude, were it not for an added implication.

This implication is, briefly, that the responsible heads of finance and industry instead of acting each for himself, must work together to achieve the common end. They must, where necessary, sacrifice this or that private advantage; and in reciprocal self-denial must seek a general advantage. It is here that formal government — political government, if you choose, comes in. Whenever in the pursuit of this objective the lone wolf, the unethical competitor, the reckless promoter, the Ishmael or Insull whose hand is against every mans, declines to join in achieving an end recognized as being for the public welfare, and threatens to drag the industry back to a state of anarchy, the government may properly be asked to apply restraint. Likewise, should the group ever use its collective power contrary to the public welfare, the government must be swift to enter and protect the public interest.

The government should assume the function of economic regulation only as a last resort, to be tried only when private initiative, inspired by high responsibility, with such assistance and balance as government can give, has finally failed. As yet there has been no final failure, because there has been no attempt; and I decline to assume that this nation is unable to meet the situation.

The final term of the high contract was for liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We have learnt a great deal of both in the past century. We know that individual liberty and individual happiness mean nothing unless both are ordered in the sense that one mans meat is not another mans poison. We know that the old “rights of personal competency — the right to read, to think, to speak, to choose and live a mode of life, must be respected at all hazards. We know that liberty to do anything which deprives others of those elemental rights is outside the protection of any compact; and that government in this regard is the maintenance of a balance, within which every individual may have a place if he will take it; in which every individual may find safety if he wishes it; in which every individual may attain such power as his ability permits, consistent with his assuming the accompanying responsibility.

Faith in America, faith in our tradition of personal responsibilities, faith in our institutions, faith in ourselves demands that we recognize the new terms of the old social contract. We shall fulfill them, as we fulfilled the obligation of the apparent Utopia which Jefferson imagined for us in 1776, and which Jefferson, Roosevelt and Wilson sought to bring to realization. We must do so, lest a rising tide of misery engendered by our common failure, engulf us all. But failure is not an American habit; and in the strength of great hope we must all shoulder our common load.

and some people who are not socialists think they know all about socialism….but, meanwhile, I am trying to figure out the answer to the question:

Are Socialists Secular humanists and are Secular humanists socialist? or Are all Socialists Secular Humanists while only some Secular Humanists Socialist or is it the other way around? Somehow, I think if I can rationalize the relationship between socialism and secular humanism, then I will be able to understand Fundamentalism and Conservativism better, not that I really want to…but it may help out when I vote Republican some day, which I don’t plan to, but you never know….

Of course, I am not really trying very hard because it is some much easier to speculate than to actually understand.

Said

“Now I have lived in two socialist countries”. And yes I can and shall elaborate on that fact.