(11 – promoted by buhdydharma )

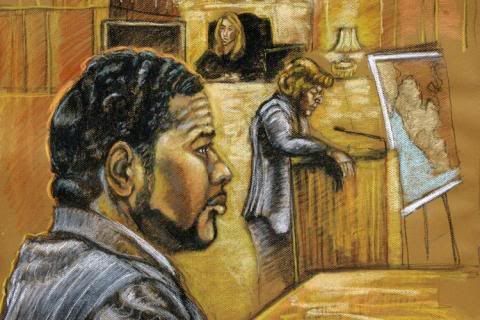

Cheers to the US for convicting Charles Emmanuel for torture he committed in Liberia. It’s a no-brainer that the US prosecuting Emmanuel while not seriously considering prosecuting US officials for torture under any law is hypocritical. However, some progressives cite the Emmanuel case as evidence of US hypocrisy and legal precedent to prosecute Bush. But, in the legal context of torture prosecutions, hypocrisy arises only if the law used to prosecute Emmanuel is applicable to Bush but the US decides against prosecution.

While Emmanuel used different means of torture than the US, torture is torture…unless the law is the one used to prosecute Emmanuel. Emmanuel was prosecuted under a US law that creates a bifurcated torture system that distinguishes between Bush’s permissible “torture lite” and criminal “severe torture.” In fact, Bush created his “torture lite” system based on the law used to prosecute Emmanuel and likely decided to prosecute precisely because it creates legal precedent that Bush can cite to either prevent a prosecution or provide a defense creating reasonable doubt in one juror’s mind to set him free. Thus, progressives spotlighting this Emmanuel case may increase the odds against prosecution of US officials.

The bifurcated nature of the US torture policy is based on distinguishing between severe, extreme acts of torture from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. Bush has decreed, and Congress has acquiesced, that his “enhanced interrogation” or “torture lite” does not constitute torture, but merely cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. The 1994 law used to prosecute Emmanuel criminalizes torture, but not torture lite.

The underlying problem is the erroneous belief that some forms of torture are acceptable because they may not appear as severe, brutal or extreme as the criminalized torture. I hope to debunk that garbage in another diary. But, unless we plan to change the existing law before seeking prosecution of Bush and his torture-loving sycophants, then we need to analyze whether we really want to advocate prosecution for Bush under the same law used to convict Emmanuel.

In order to decide whether Bush officials can be prosecuted under the same torture law as Emmanuel, the prosecutor will determine the meaning of torture under that law by evaluating some key sources, such as the statute and legislative history. While legal advice to the defendant is not controlling, it may be considered for issues of intent.

(1) The 1994 Torture Law Creates Two-Tiered Torture System of Torture Lite versus Severe Torture.

Emmanuel was prosecuted under a 1994 law that Congress enacted to criminalize some but not all forms of torture. Rather, torture is limited to what some perceive as severe or extreme brutality when committed by persons who also had the specific intent to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering. Severe mental pain or suffering is defined to further limit torture to specific types of harm or pain, such as that arising from prolonged mental harm caused by the intentional infliction of severe physical pain, the use of mind-altering substances, or threat of imminent death of the person being tortured or another person, such as family.

Emmanuel was prosecuted under a 1994 law that Congress enacted to criminalize some but not all forms of torture. Rather, torture is limited to what some perceive as severe or extreme brutality when committed by persons who also had the specific intent to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering. Severe mental pain or suffering is defined to further limit torture to specific types of harm or pain, such as that arising from prolonged mental harm caused by the intentional infliction of severe physical pain, the use of mind-altering substances, or threat of imminent death of the person being tortured or another person, such as family.

Thus, the 1994 law provides a few loopholes for Bush: The torture must be severe and requires specific intent, an element which is discussed more below because it can “legalize” any torture and thus virtually eliminate any ostensible ban. (Another loophole is that the 1994 law did not apply to military bases and buildings abroad until 2004 and thus may not be applicable to torture committed prior to that date on US military bases and perhaps ghost rendition ships.)

Next, the prosecutor will review legislative history to better determine what is encompassed by “severe” torture to see if US officials can be prosecuted under this law.

(2) Congress limited torture to extreme pain that is more severe than cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

The 1994 torture law used to prosecute Emmanuel is the law that Congress enacted to implement the US obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). CAT defines torture as “any act” which causes “severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental” which is intentionally inflicted for the purpose of obtaining information, a confession, punishment, intimidation, coercion or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.

The 1994 torture law used to prosecute Emmanuel is the law that Congress enacted to implement the US obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). CAT defines torture as “any act” which causes “severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental” which is intentionally inflicted for the purpose of obtaining information, a confession, punishment, intimidation, coercion or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.

CAT made it clear that there should be no bifurcated torture system (pdf file) which provides “circumstances or emergencies where torture could be permitted.” However, CAT provided a window for a bifurcated system and the US grabbed it.

When seeking Senate approval, President Reagan made it clear that torture under CAT was limited to severe or extreme acts of mistreatment (pdf file):

[T]he Convention’s definition of torture was intended to be interpreted in a “relatively limited fashion, corresponding to the common understanding of torture as an extreme practice which is universally condemned.” For example, the State Department suggested that rough treatment falling into the category of police brutality, “while deplorable, does not amount to ‘torture'” for purposes of the Convention, which is “usually reserved for extreme, deliberate, and unusually cruel practices … [such as] sustained systematic beating, application of electric currents to sensitive parts of the body, and tying up or hanging in positions that cause extreme pain.” This understanding of torture as a severe form of mistreatment is further made clear by CAT Article 16, which obligates Convention parties to “prevent in any territory under [their] jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to acts of torture,” thereby indicating that not all forms of inhumane treatment constitute torture.

Thus, the US did not specifically criminalize cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. Rather, prosecution for such acts would be based on general criminal laws, such as assault and murder or Constitutional mandates against cruel or unusual punishment. However, Bush maintains that the US implemented CAT so that Constitutional protections are not applicable to persons who are not US citizens. Therefore, under Bush, there is carte blanche to treat foreign prisoners in cruel, inhuman or degrading manners.

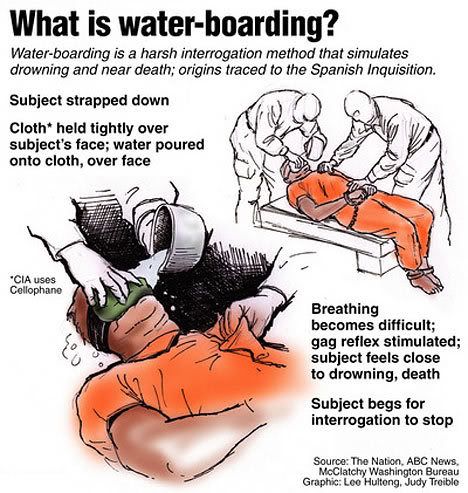

(3) Bush classifies waterboarding as a form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment which does not constitute torture.

Bush and Congress have determined that waterboarding is not torture, and thus not criminal under the 1994 law. Rather, the Army Field Manual classifies waterboarding as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, which also includes other painful acts, such as beatings, electric shock, and burns. In fact, even Bush recognized that if torture was defined to include “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment” that it would prevent his “enhanced or harsh interrogation.”

Bush and Congress have determined that waterboarding is not torture, and thus not criminal under the 1994 law. Rather, the Army Field Manual classifies waterboarding as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, which also includes other painful acts, such as beatings, electric shock, and burns. In fact, even Bush recognized that if torture was defined to include “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment” that it would prevent his “enhanced or harsh interrogation.”

(4) Bush obtained legal advice that his torture lite was permissible and did not constitute torture.

The two infamous torture memos used to justify Bush’s torture lite are based upon interpreting the meaning of torture in the 1994 law. Yoo maintained that the narrow definition of torture that Congress enacted into the 1994 law limits torture to extreme acts that are distinguishable from acts of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

Yoo used specific intent to legalize even extreme acts as not criminal torture. As explained by Yoo, if the specific intent of the method is not to inflict pain but to disorient the prisoner, such as the use of reduced sleep, stress positions or isolation from other prisoners, then the method does not constitute torture.

Yoo used specific intent to legalize even extreme acts as not criminal torture. As explained by Yoo, if the specific intent of the method is not to inflict pain but to disorient the prisoner, such as the use of reduced sleep, stress positions or isolation from other prisoners, then the method does not constitute torture.

This view of specific intent essentially swallows up the ban against torture. For example, the government can argue that waterboarding is not torture because the specific intent was interrogation, not the infliction of severe pain. The 2004 memo explains further that it is “unlikely” (pdf file) that a person who “acted in good faith” and “after reasonable investigation establishing that his conduct would not inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering, would possess the specific intent required to violate the federal torture statute.” This explains why torture lite was demonstrated to the WH officials when the CIA was seeking written approval of methods used.

(5) Legal precedent for the 1994 law is now limited to the extreme torture committed by Emmanuel.

When some advocate that the Emmanuel case is legal precedent to prosecute Bush, this means that the prosecutor would have to view the facts of torture in the Emmanuel case as similar to the torture used by Bush. A hypothetical example shows how legal precedent is based on the facts in cases that are used as building blocks to establish the meaning of words in statutes. Let’s say that California just enacted a law that defined rape as “sexual acts penetrating the vagina or anus by force without consent.” In the 1st case ever prosecuted under this law, the woman was forced to commit sexual acts at the point of a gun. “Force” under this law would then be interpreted to mean some deadly force until other cases added to the mix. The 2nd case involved a man compelled to commit sexual acts after he was beaten. Now, force would be defined to include physical violence as well as deadly force.

The point is that the Emmanuel prosecution was the first case ever prosecuted under the 1994 law, which defines torture as “severe physical or mental pain or suffering.” The prosecutors proved torture by killings, “electric shocks, lit cigarettes, molten plastic, hot irons, stabbings with bayonets and even biting ants shoveled onto people’s bodies” as well as imprisonment in “pits partially filled with water and covered with iron bars and barbed wire.” Whether we like it or not, these acts of torture fit into the extreme, brutal acts discussed in the legislative history for this law and which fit the perception of many Americans. During the jury selection process, prospective jurors “gasped” when they were informed of the “gruesome details of torture” alleged, which included burning people with clothes irons, shocking genitals with electrical charges, cutting genitals, forcing people to sodomize each other and cutting off people’s heads.

The point is that the Emmanuel prosecution was the first case ever prosecuted under the 1994 law, which defines torture as “severe physical or mental pain or suffering.” The prosecutors proved torture by killings, “electric shocks, lit cigarettes, molten plastic, hot irons, stabbings with bayonets and even biting ants shoveled onto people’s bodies” as well as imprisonment in “pits partially filled with water and covered with iron bars and barbed wire.” Whether we like it or not, these acts of torture fit into the extreme, brutal acts discussed in the legislative history for this law and which fit the perception of many Americans. During the jury selection process, prospective jurors “gasped” when they were informed of the “gruesome details of torture” alleged, which included burning people with clothes irons, shocking genitals with electrical charges, cutting genitals, forcing people to sodomize each other and cutting off people’s heads.

This does not mean that a prosecutor can not decide that torture lite is torture under the 1994 law. It just means that it would be an uphill battle given that the words in the statute, its legislative history, and US policy for years have distinguished between torture and torture lite. It just seems to make more sense to seek prosecution based on the Geneva Conventions or Common Article 3 because both ban torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

can’t find the coding for special prosecutor badge, but indicated in tip jar that DD has petition waiting for signatures!

in 1981 because they chose to go on strike to demand better working conditions and enhance air traffic safety, is it asking too much for Obama to fire a few dozen spear carriers who committed war crimes and to prosecute a dozen or so officials who devised the policies to permit and promote the war crimes?

Oh, and while we’re at it, should we not expect President Obama and AG Holder to turn some attention to the officials who directed warrantless wiretapping and data mining, as well as to the key operatives, such as then DIRNSA and now DCIA Michael Hayden, who implemented these illegal “unitary executive” programs?

Or will the final score turn out to be: Reagan: 11,345 ( for teaching a Republican lesson to organized labor) versus Obama: 0 (for completely wussing out on teaching a lesson to war criminals)?

I agree that the legal reliance should be on the Geneva Conventions and Common Article 3 and other national and international laws.

Torture is torture. Can one form of torture be considered less painful physically and mentally than another form? Essentially, it seems they’re trying to draw a distinction and I don’t think one can be had. Every single method mentioned and used in either scenario is torture period.

On May 6, 2008, Marjorie Cohn, President, National Lawyers Guild Professor, Thomas Jefferson School of Law, testified before the House Judiciary Committee– the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties: