So I know you were just sitting around wondering, “What are the origins of the modern police state?,” and maybe, “Can an effort at genocide, if sustained long enough, actually work?,” or possibly, “What would happen if a bunch of religious zealots were in a position to exercise spiritual, temporal, political, and military authority over all they survey?” Well, Pope Innocent III, the same guy who launched the Fourth Crusade, certainly asked himself these questions, and he sought to answer them through direct action.

So join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, to get a glimpse of a nobly enlightened culture as it is extinguished by the hate-filled love of the Medieval Church. We’ll also see the heretical Cathars subjected to travesties that only these people would not find barbaric…

Historiorant: This diary originally appeared under the title “The Albigensian and Children’s Crusades” almost three years to the day ago – on April 31, 2006. It was then part 5 of an ongoing series on the Crusades; tonight, an edited and updated revision seems an appropriate contribution to the recent discussions about the role of torture in our society, culture, and policy.

While the tragedy of the Albigensian Crusade is perhaps less instructive vis-à-vis the Iraq conflict specifically than some of the other Christian holy wars, it does present us with plausible nightmare scenarios to be guarded against – for in them, we see just how far a Christian theocracy would be willing to go to eradicate what it considers deviant beliefs, as well as the compromises in morality that can occur when society lets the whole the-heretics-are-destroying-your-faith line of justification go too far.

It happened with such speed, ferocity, and overwhelming force that the Cathars, who the Church had branded heretics, were completely stamped out by the 15th century. Their culture, a beacon of tolerance and liberal thought complete with a troubadour soundtrack, was ground into the dust by the sandal of the Shepherd, their music silenced by the Inquisitor’s whip. Rome’s target would be Languedoc, the region of southwestern France that stretches from the Rhone to the foothills of the Pyrenees, and includes the ancient fortress cities of Toulouse, Montpelier, and Carcassonne – plus the unbelievers who lived there. Half a million people – basically, all of the Cathars and a whole bunch of Catholics who stood with them – were slaughtered over a forty-year period, and the land would never really recover. Along the way, the Church would explore the techniques that laid the foundations of the modern police state: propaganda, paid informants, a cadre of dedicated zealots, and, of course, torture.

It happened with such speed, ferocity, and overwhelming force that the Cathars, who the Church had branded heretics, were completely stamped out by the 15th century. Their culture, a beacon of tolerance and liberal thought complete with a troubadour soundtrack, was ground into the dust by the sandal of the Shepherd, their music silenced by the Inquisitor’s whip. Rome’s target would be Languedoc, the region of southwestern France that stretches from the Rhone to the foothills of the Pyrenees, and includes the ancient fortress cities of Toulouse, Montpelier, and Carcassonne – plus the unbelievers who lived there. Half a million people – basically, all of the Cathars and a whole bunch of Catholics who stood with them – were slaughtered over a forty-year period, and the land would never really recover. Along the way, the Church would explore the techniques that laid the foundations of the modern police state: propaganda, paid informants, a cadre of dedicated zealots, and, of course, torture.

Who Would Jesus Bomb, indeed.

Oc

Languedoc takes its name from Occitan, the language spoken by inhabitants of southwestern France. Although derived from Latin like other Romance languages, it is not a dialect of French, nor a patois of French and Catalan, but a separate and distinct language that was – like Gaelic, within its context – suppressed by regimes that had no interest in seeing proto-nationalist movements grow from linguistic roots.

It was the language of the Troubadours, poet-musicians who explored the ideas of courtly love, conviviality, and paratge – a concept perhaps best described as a combination of honor, courtesy, chivalry, and gentility, though those very words derive their respective definitions from an understanding of paratge. Troubadours were spread across all of Occitania, and counted among their number wandering minstrels (which annoyed the Church), nobles and kings (which angered the Church), and even some bishops and priests (which pissed off the Church beyond all hope of reconciliation). A look a some of their lyrics – by a lady, no less! – might help to clarify why they were arousing the ire of Innocent III:

“Estat ai en greu cossirier”

Cindessa de Dia, circa. AD 1200

Estat ai en greu cossirier / per un cavallier q’ai agut,

e voill sia totz temps saubut / cum eu l’ai amat a sorbrier;

ara vei q’ieu sui trahida / car eu non li donei m’amor,

don ai estat en gran error / en lieig quand sui vestida.

Ben volria mon cavalier / tener un ser e mos bratz nut,

q’el s’en tengra per ereubut / sol q’a lui fezes cosseiller;

car plus m’en sui abellida / no fetz Floris de Blanchaflor:

eu l’autrei mon cor e m’amor / mon sen, mos houills e ma vida.

Bels amics, avinens e bos, / Coraus tenrai e mon poder?

e que jagues ab vos un ser / e qeus des un bais amoros!

Sapchatz, gran talan n’auria / qeus tengues en luoc de marit,

ab so que m’aguessetz plevit / de far tot so qu’eu volria.“I was Plunged into Deep Distress”

The Countess of Die, circa. AD 1200

I was plunged into deep distress / by a knight who wooed me, and I wish to confess for all time / how passionately I loved him;

Now I feel myself betrayed, / for I did not tell him of my love.

therefore I suffer great distress / in bed and when I am fully dressed.

Would that my knight might one night / lie naked in my arms

and find myself in ecstasy / with me as his pillow.

For I am more in love with him / than Floris was with Blanchfleur.

to him I give my heart and love, / my reason, eyes and life.

Handsome friend, tender and good, / when will you be mine?

Oh, to spend with you but one night / to impart the kiss of love!

Know that with passion I cherish / the hope of you in my husband’s place,

as soon as you have sworn to me / that you will fulfill my every wish.

Occitania, or the land of the Langue d’Oc, was an area of high culture, great artistic achievement, and raw natural beauty. Mighty castles squatted atop granite outcrops, rich fields and vineyards kept well-stocked the vibrant markets of the towns, and an atmosphere of tolerance and openness complemented the Mediterranean climate. Religious tolerance permeated the society of Languedoc, and allowed for the broad practice of Catharism, a unique branch of the Christian tree has rather obscure – and somewhat Persian – beginnings, but by the late 12th century was widely practiced across the whole of Occitan.

Occitania, or the land of the Langue d’Oc, was an area of high culture, great artistic achievement, and raw natural beauty. Mighty castles squatted atop granite outcrops, rich fields and vineyards kept well-stocked the vibrant markets of the towns, and an atmosphere of tolerance and openness complemented the Mediterranean climate. Religious tolerance permeated the society of Languedoc, and allowed for the broad practice of Catharism, a unique branch of the Christian tree has rather obscure – and somewhat Persian – beginnings, but by the late 12th century was widely practiced across the whole of Occitan.

Cathars: The non-Da Vinci Code version

I’ll leave to others the debate over whether or not the Cathars harbored the secret line of Jesus’ prodigy, but they did claim to faithfully follow the practices of the earliest Christians. If this is indeed the case, then one can easily see why the Catholic Encyclopedia would say this about them:

The Catharist system was a simultaneous attack on the Catholic Church and the then existing State. The Church was directly assailed in its doctrine and hierarchy. The denial of the value of oaths, and the suppression, at least in theory, of the right to punish, undermined the basis of the Christian State. But the worst danger was that the triumph of the heretical principles meant the extinction of the human race. This annihilation was the direct consequence of the Catharist doctrine, that all intercourse between the sexes ought to be avoided and that suicide or the Endura, under certain circumstances, is not only lawful but commendable.

Of course, one would expect the perpetrators of an historical crime to try to minimize its impact by portraying their victims in their dimmest possible light, but much of what the Church claims here could well fall into the true-but-taken-out-of-context category. As I’ve already done several times in this diary, I’ll turn to the excellent languedoc-france.info website – manual v-chip alert: thumbnail linking to naturist destinations on un-prudish front page – to explain just why the Cathars so annoyed the Catholic power structure:

Cathars claimed to have preserved practices and beliefs of earliest Christians, a claim which was then considered absurd, but which historians and theologians now take seriously. Like many ancient gnostic sects they made a distinction between the inner Elect and the mass of believers. The Elect led ascetic lives: they spent their time meditating and teaching when not earning their living. They observed strict rules prohibiting lying and swearing. They did not eat meat, nor engage in sex, nor war, and looked forward to their release from the cycle of reincarnation. Both men and women could become members of the Elect. Male members of the Elect went from village to village, traveling in pairs as they said the original apostles had done.

Cathars reasoned that a good God could not have created such an evil world as this, and concluded that there must be two gods: a good one who created good things and a bad one who created bad ones. It was easy to tell which was which because the good things were all immaterial and bad ones all material. The bad God delighted in trapping immaterial spirits in his own material creations, which accounted for human beings and, according to some, animals as well. When people died the bad God would imprison the newly released spirit in another body, human or animal. When people became members of the Elect, the bad god lost his power to trap their spirits, and the cycle of reincarnation was broken, allowing the spirit to return to the Good God’s realm of light. Cathars explicitly worshipped the good God, and despised the work of the bad God, including all material objects. Material objects incidentally included the material goods of the Catholic Church: not only rich vestments, jewel encrusted relicaries and expensive palaces, but ordinary churches, statues and crucifixes. Cathar ideas were not popular among the Catholic hierarchy, but the two religions continued side by side for many years without any noticeable problems.

Cathars v. Catholics

The Cathars read their Bible, and they were known to call out the Church on its various hypocrisies in its regard. Matthew 6:24 was a favorite:

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.

The Cathars saw the Church as worshipping the evil, the material. Cathars did not, for example, worship the relics of saints, and found the worship of the cross – a material device of torture – as proof positive that the Church was in fact paying homage to the Devil. The saw the rites and ceremonies of the Church as perverted from their original intent, and pope as an agent of great evil. They cited the Gospel of Matthew to back them up:

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

In fact, that passage earned the Roman Catholic and Apostolic Church the Cathar nickname “Church of Wolves” (lest ye be feeling pangs of sympathy for the pontiff and his flock, don’t fret: the Pope had a nicknaming propaganda machine of his own, which we’ll get to in a minute). Regardless, the Church wasn’t doing much to help its case:

Other Catholic beliefs and practices seemed to provide confirmation. Anyone who attached great value to material things was at best mistaken and at worst a disciple of the Bad God, and here again the Roman Church seemed to qualify. Cardinals, bishops and priests lived in great luxury and dressed in gorgeous robes. Even Churchmen recognised the fault of their fellow shepherds. Pope Innocent III, the richest man in Christendom, noted of the Archbishop of Narbonne:

“…He knows no other god but money and has a purse where his heart should be. His monks and canons take mistresses and live by usury… Throughout the region the prelates are the laughing stock of the laity.”

Self-loathing no doubt influenced the Pope’s decision to launch a war against other Christians within Europe: high-living Catholic clergymen were perceived by people they ostensibly controlled to be relegated to the moral low ground when faced with even something as simple as choice of diet. Cathars – especially the Parfaits – were strict vegetarians. In fact, they probably would have been completely vegan if they’d understood that fish reproduce sexually – their prohibition was not against eating flesh because it had once been alive, but because the act of sexual reproduction that created it had trapped a soul in a material body. Fish were thought to spring into life spontaneously, and so were kosher (as it were). A slightly different application of this sort of Medieval creationism could explain why it’s okay for Catholics to eat fish, but not land-stalking meat, on Fridays during Lent.

Catholics v. Cathars

The Cathars were an increasing concern to the Church hierarchy as the 12th century turned into the 13th, and the Holy See tried incrementally-more-diabolical methods to bring the dualists back into the fold.

First was propaganda: They began with re-branding the sect away from the earlier “Albigensian,” which was based on the belief that the heretics were concentrated in and around the town of Albi (also the reason the crusade against them is most commonly known as the Albigensian Crusade. “Cathar” is a word applied by the Catholic Church to the people we’ve been discussing; they called themselves Christians. “Cathar” itself is apparently a bastardization of a 12th-century German word that describes the application of one’s lips to the nether regions of a cat, but has origins much older than that:

The name Cathar is widely claimed to derive from the Greek word Katharoi meaning “the pure”. Many scholars assert that the name was initially used by Cathar believers of the inner Elect, and that it was later extended to the whole body of believers.

The term was first used (in Germany) by Eckbert, Abbot of the double abbey of Schönau around 1163, apparently based on the bizarre idea that they, like other heretics, performed obscene acts with cats. This was a common and apparently unfounded accusation of Medieval Catholics against anyone that they regarded as heretical.

But everyone who knew the Cathars and their simple asceticism assumed that the word derived from katharos, the Greek for pure. The Cathars, French Cathares, Latin Cathari, rarely called themselves by any of these names.

This general theme can also be detected in yet another of slang’s surprising etymologies:

This was an effective and persistent accusation. Remember that Cathars were given many names. When they first appeared in Western Europe they were known to have come from the area be know as Bulgaria. They were thus called Bulgres, a word that Church propaganda turned into French Bougre and English Bugger.

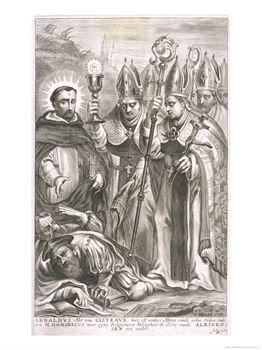

Next was evangelizing: a Spanish guy named Dominic de Guzman, the best preacher the Pope had in his arsenal, was dispatched to Languedoc in 1205. He failed to make many converts, but he did appreciate the asceticism of the Cathar Parfaits, the wandering preachers and spiritual leaders who were a lot more like Buddhist missionaries or Hindu mystics than the opulence-loving Christian clergy. Guzman was so impressed, in fact, that he constructed a monastery based on the austere Cather model just outside Languedoc.

Next was evangelizing: a Spanish guy named Dominic de Guzman, the best preacher the Pope had in his arsenal, was dispatched to Languedoc in 1205. He failed to make many converts, but he did appreciate the asceticism of the Cathar Parfaits, the wandering preachers and spiritual leaders who were a lot more like Buddhist missionaries or Hindu mystics than the opulence-loving Christian clergy. Guzman was so impressed, in fact, that he constructed a monastery based on the austere Cather model just outside Languedoc.

Guzman and his boys set about on a series of debates with various Parfaits, which they seem to have lost miserably. By way of example: Before a literate, educated, and cultured Languedoc audience in Pamiers in 1207, one of Guzman’s acolytes insulted the revered holy woman, Esclarmonde of Foix, by saying,

“Go back to your spinning, woman. It is not proper for you to speak in a debate of this sort.”

– probably not the first public utterance of this rather vapid perspective on the role of women in society, but illustrative for its casual, arrogant delivery before a wholly unreceptive audience.

The Catholic Church takes a more nuanced, Cheneyesque view of Dominic’s debates with the Albigensian heretics. Here’s the Catholic Encyclopedia‘s version:

Theological disputations played a prominent part in the propaganda of the heretics. Dominic and his companion, therefore, lost no time in engaging their opponents in this kind of theological exposition. Whenever the opportunity offered, they accepted the gage of battle. The thorough training that the saint had received at Palencia now proved of inestimable value to him in his encounters with the heretics. Unable to refute his arguments or counteract the influence of his preaching, they visited their hatred upon him by means of repeated insults and threats of physical violence. With Prouille for his head-quarters, he laboured by turns in Fanjeaux, Montpellier, Servian, Béziers, and Carcassonne. Early in his apostolate around Prouille the saint realized the necessity of an institution that would protect the women of that country from the influence of the heretics. Many of them had already embraced Albigensianism and were its most active propagandists. These women erected convents, to which the children of the Catholic nobility were often sent-for want of something better-to receive an education, and, in effect, if not on purpose, to be tainted with the spirit of heresy. It was needful, too, that women converted from heresy should be safeguarded against the evil influence of their own homes. To supply these deficiencies, Saint Dominic, with the permission of Foulques, Bishop of Toulouse, established a convent at Prouille in 1206. To this community, and afterwards to that of Saint Sixtus, at Rome, he gave the rule and constitutions which have ever since guided the nuns of the Second Order of Saint Dominic.

The one point upon which both sources seem to agree is that the monastery-founder’s logic was not well regarded by the people of Languedoc. Indeed, there is case to be made that says that the Albigensian Crusade was due in part to a desire for vengeance by the future St. Dominic.

And a final solution: Dominic got his crusade in 1208, but was unable to gain permission from Innocent III to found the gang of “preaching friars” (like his monastery, based on the Cathar model) he envisioned before the old, less-than-innocent pope died in 1215. His successor, Honorius III, allowed for the establishment of the Dominican Order the following year. Dominic died in 1221; twelve years later, the fledgling order was charged with the complete extirpation of the Cathars in the form of an Inquisition, and they began carrying out their task with a psychopathic gusto that would have filled their founder with <insert emotion as your knowledge/faith sees fit>. Dominic was made a saint in 1234.

And a final solution: Dominic got his crusade in 1208, but was unable to gain permission from Innocent III to found the gang of “preaching friars” (like his monastery, based on the Cathar model) he envisioned before the old, less-than-innocent pope died in 1215. His successor, Honorius III, allowed for the establishment of the Dominican Order the following year. Dominic died in 1221; twelve years later, the fledgling order was charged with the complete extirpation of the Cathars in the form of an Inquisition, and they began carrying out their task with a psychopathic gusto that would have filled their founder with <insert emotion as your knowledge/faith sees fit>. Dominic was made a saint in 1234.

An horrific precedent

Innocent III called for a crusade against the Cathars in 1208, the year after Dominic’s Colbert treatment at the hands of Cathar Elect. Initially led by the Cistercian Abbot of Citeaux, it attracted a number of landless and small-manor-holding nobles from all over the French-speaking regions of the north, as there was a bit of land problem starting to afflict feudal Europe. Rules of primogenitor inheritance, combined with dynastic claims to lands and titles, had held sway over land distribution in Europe for hundreds of years, which meant that each generation was divvying up smaller and smaller portions of the peasant-labor pie. The brutal fact was, if a knight was errant to rule over a broad swath of land and a whole gaggle of serfs, he was going to have to take it from someone. When the Pope himself declared a crusade in the region immediately south of the French homeland, it lent an air of legitimacy to what for many was a land-grab as baldfaced as the one in Oklahoma in 1889.

The crusaders were led by one such “noble,” a guy named Simon de Montfort, but only after the Abbot-Commander had had a chance to display his complete and utter lack of humanity at the town of Beziers in 1209. There, a community of perhaps 200 Cathars enjoyed the protection of a much larger (and quite sympathetic) Catholic population. After a brief siege, the town’s defenses were breached, and the slaughter began. At one point during the butchery, the Abbot-Commander was asked how the French army should tell apart Catholic and Cathar, to which he reportedly replied,

The crusaders were led by one such “noble,” a guy named Simon de Montfort, but only after the Abbot-Commander had had a chance to display his complete and utter lack of humanity at the town of Beziers in 1209. There, a community of perhaps 200 Cathars enjoyed the protection of a much larger (and quite sympathetic) Catholic population. After a brief siege, the town’s defenses were breached, and the slaughter began. At one point during the butchery, the Abbot-Commander was asked how the French army should tell apart Catholic and Cathar, to which he reportedly replied,

“Kill them all – the Lord will know His own.”

– again, probably not the first utterance of this rather cynical profession of faith, but you weren’t thinking that some guy who sells tee shirts in the back of Soldier of Fortune magazine coined it, were you?

The list of horrors at Beziers goes on: 7000 slaughtered in the church in which they had sought refuge, dozens of pacifist Cathars burned at the stake, etc. In the end, the Abbot-Commander wrote back to Rome and proudly proclaimed that his men had put 20,000 men, women, and children to the sword, and had spared no one in the now-razed town.

And it doesn’t stop there:

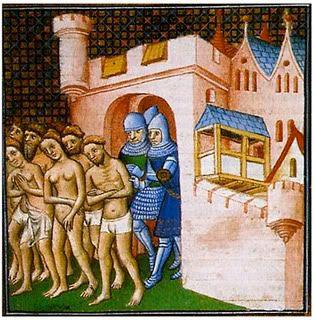

Carcassonne, 1209: After a 2-week siege, the Cathar defenders are forced to surrender when their commander is taken prisoner while negotiating under a flag of truce. They are evicted from the city “carrying nothing but their sins.” Probably the only reason they were not killed outright was because the crusaders began looting before the last inhabitants had been driven from the city.

Carcassonne, 1209: After a 2-week siege, the Cathar defenders are forced to surrender when their commander is taken prisoner while negotiating under a flag of truce. They are evicted from the city “carrying nothing but their sins.” Probably the only reason they were not killed outright was because the crusaders began looting before the last inhabitants had been driven from the city.

Bram, 1210: 100 prisoners have their noses cropped, their lips cut off, and their eyes gouged out after surrendering to the mercy of the Lord’s host. Scratch that: the crusaders leave one guy with one eye, so that he can lead the others to safety. Like WWI soldiers stumbling out of a cloud of mustard gas, the pathetic chain made its way back to the Cathar town of Cabaret.

Minerve, 1210: 150 Cathars voluntarily martyr themselves in Catholic pyres rather than abjure their faith.

Lavour, 1211: 90 Cathar knights are hanged. The chatelaine is tossed alive into a well, then stones are tossed in until her screams can no longer be heard. 400 Cathars are burned alive.

The fortunes of war and the castles of the Cathars

The Count of Toulouse, Raymond IV, had tried everything from allying himself with the crusaders (thus entitling his lands to papal protection) to allying with fellow Occitanians against the relentless foe, but nothing really worked until Pedro II of Aragon won an important victory against the Moors (putting them into a slow-but-relentless southward retreat that wouldn’t be over for nearly three more centuries) and was able to redirect his attention north of the Pyrenees.

Regrettably, Pedro had a bit of a showy streak to him, and got himself killed in hand-to-hand combat during a siege that he and Raymond had already won. Thus, after a brief period during which the forces of Languedoc had the upper hand, the tides again turned and the Cathars increasingly found themselves on the wrong side of the siege walls. Hordes of hungry refugees fled from castle to castle, straining resources and causing the sieges to be surprisingly short, given the apparent defensive situation of many of the Cathar castles.

Xenophongroup hosts a site with pictures and stories of Cathar castles; it’s well worth a look. Here are a couple of the more spectacular, along with their stories:

Montségur, though in ruins, is one of the most photographed ‘icons’ of the spectacular fortresses of the Cathars. It is famous not only for its awsome position high on a rock mountain, but for the dramatic 1243 siege. The fortress was received many refuges form the early part of the crusade. It was called by the crusaders ‘Satan’s Synagogue’. However, its remote location protected it until St. Louis IX of France felt it necessary to take it following a killing of some Inquisitors in Avignonet in 1242. The army that took the fortress was led by the Seneschal of Carcassonne, Hugue des Arcis. The siege, involving heavy use of some of the largest mechanical artillery of its day, lasted from May 1243 to March 1244. The surrender terms agreed to spare any heretic that recanted. None did, and they were joined by some Catholics (who converted to Catherism at this moment) as well over 200 individual marched down the mountain and “threw themselves on the fire.” The site is a popular visit for anyone interested the study of the Cathars. A fine museum is located in the village of Montségur is at the base of the 1,207 meters mountain.

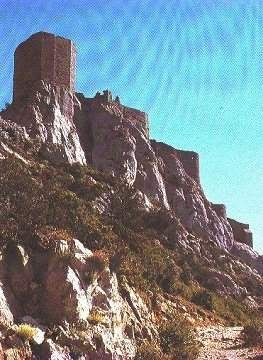

Quéribus (Aude) was the last of the Cathar

fortresses to fall in 1255. In the eleventh century it belonged to the comtes de Barcelona and later the king of Aragon. Its isolation protected it from being attacked by the earlier crusaders. This small castle is perched upon a narrow spur that is accessed by a flight of steps carved into the rock. The keep and wall fortifications were modified since the Cathars’ era, as Quéribus was an important frontier post between France ad Spain until the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), when it was abandoned. It is one of the legendary hiding places for the Holy Grail

But in the end…

Effective Cathar resistance ended with the fall of Queribus in 1255, though remnants of Cathar belief remained strong enough that Dominicans continued their Inquisition well into the next century. Here’s an excerpt from the confession of Beatrice of Dalou, speaking about the few surviving pockets of Cathars decades after the purges:

They remain in Lombardy, because they do not dare do live here, where the wolves and the dogs persecute them. The wolves and the dogs are the bishops and the Preaching Friars (Dominicans) who persecute the good Christians and chase them from the country.

From the Confession of Béatrice de Planissoles, widow of Otho Lagleize of Dalou, The year of the Lord 1320, the Wednesday before the feast of St. James (July 23rd, silly). Worth a gander in its entirety, especially for the matter-of-fact way this 14th-century woman describes her impassioned affair with a local priest.

The Dominicans established the mechanisms of the first modern police state in the former lands of Languedoc. Public torture and execution, coupled with ironfisted military subjugation, kept the cowed and enslaved population in line. Spies and informants were encouraged to rat out their neighbors for their own benefit, and when there were no more Cathars to persecute, they turned their attention to the ever-present problem of witches (who seemed to crop up in every place a woman displayed independent thought). Jews, who had achieved high status under the openly tolerant Cathar lords, were driven from their ancestral (some going back to Diaspora-era) properties, and thousands were tortured and killed at the hands of the Inquisitors. In the late 1340’s, the Dominicans would lead accelerated persecutions against both of these groups as a means of diverting attention away from the Church’s powerlessness before the scourge of the Black Death.

The Dominicans established the mechanisms of the first modern police state in the former lands of Languedoc. Public torture and execution, coupled with ironfisted military subjugation, kept the cowed and enslaved population in line. Spies and informants were encouraged to rat out their neighbors for their own benefit, and when there were no more Cathars to persecute, they turned their attention to the ever-present problem of witches (who seemed to crop up in every place a woman displayed independent thought). Jews, who had achieved high status under the openly tolerant Cathar lords, were driven from their ancestral (some going back to Diaspora-era) properties, and thousands were tortured and killed at the hands of the Inquisitors. In the late 1340’s, the Dominicans would lead accelerated persecutions against both of these groups as a means of diverting attention away from the Church’s powerlessness before the scourge of the Black Death.

The moral of the story/Historiorant

The high culture of Languedoc survives only in fragments today; we’ll never know with truly intimate detail the philosophies of the troubadours, nor the most secret beliefs of the Cathar Elect. Millions of people around the world smile smugly at their knowledge of the Cathars, freshly gleaned from watching a DVD of The Da Vinci Code, but they’ll know only a very small part of the story – and one that represents a controversial interpretation of the facts, to say the least.

The high culture of Languedoc survives only in fragments today; we’ll never know with truly intimate detail the philosophies of the troubadours, nor the most secret beliefs of the Cathar Elect. Millions of people around the world smile smugly at their knowledge of the Cathars, freshly gleaned from watching a DVD of The Da Vinci Code, but they’ll know only a very small part of the story – and one that represents a controversial interpretation of the facts, to say the least.

In truth, the same goes for us. There’s a lot I’ve had to leave out – epic stories of shifting alliances, excommunications, Simon of Montfort getting killed by a rock fired from a mangonel, and acts of martyrdom that challenge the soul – in favor of spending some time getting to know the Cathars. I’d also like to mention that I don’t hold any special grudges toward Catholics in general or Dominicans in particular; I simply try’n calls `em as I sees `em. I also think it’s important to understand the nature of the Medieval Catholic mind, if only because that particular worldview – first established and codified here, in Laguedoc – leads to so many other tragedies down the historical road: the Male Maleficarum witch hunts, the reconquista in Spain, and the subjugation of the natives of the Americas, to name just a few.

And now, the tinfoil hat question: Do New Agers, suburban Buddhists, and free-thinking liberals everywhere have something to learn from the stories of this tragic crusade, this successful early effort at genocide? Something to fear, to guard against, perhaps? Anybody (else) see these events playing out in a modern context (too)?

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

1 comments

Author

Thinking about those Catholics who converted just so they could die in the same pyres as their Cathar friends and neighbors…