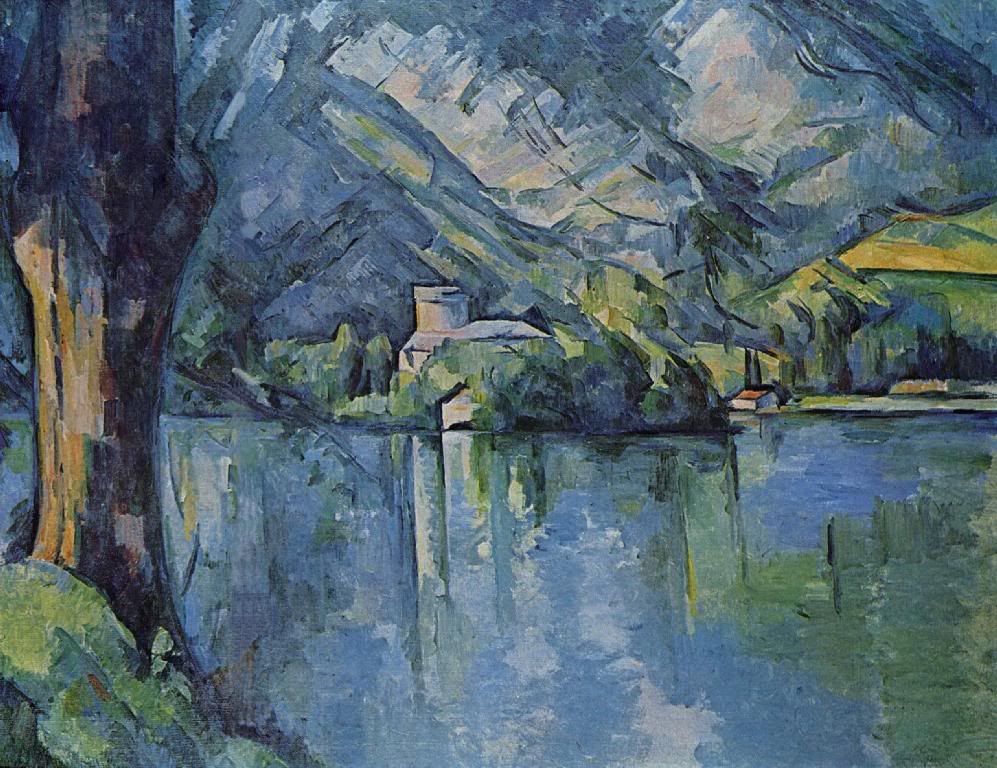

One’s favorite paintings are purely subjective. Since I first discovered but a poster of it, Paul Cézanne’s Le Lac d’Annecy has been among the handful of mine. The real thing resides in London’s Courtauld Gallery, but I first saw it when the Courtauld Institute was being remodeled, and the collection was shipped exclusively to Toronto. The future Mrs. T and I were headed to a friend’s wedding, in rural Ontario, and had decided to drive across the country. I’d never been to Toronto, so we planned to stay for a few days. We drove in from Indiana, had our car searched at the border, and only made it to our hotel after midnight. Except that there had been a screw-up with the reservation, so it wasn’t our hotel. And it was Gay Pride Week, which meant that almost every room in the city was booked. But the hotel manager managed to reach a friend who ran another hotel, and we ended up in a lavish business suite for the price of a small room. We got to bed around 3 a.m., woke the next day, went out exploring, and saw the banners on lampposts: The Courtauld Collection! In Toronto! Right then! It became our first stop!

(massive version here)

The haunting magic of the painting simply cannot be captured online. For one thing, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism are very much about physical texture, and unless you can see the brush strokes, you’re not really seeing the painting. And in Cézanne’s case, and specifically with this work, that often meant palette knife strokes, because Cézanne’s fascination with intersecting planes often led him to craft his art with his knife rather than with a paintbrush. And when we found the room with this painting, I could not leave. The future Mrs. T later told me she began to wonder if I would try to walk out with it.

My enchantment led a couple other visitors to inquire about it. I began explaining. A small crowd gathered. I told them to stand ten to fifteen feet back, relax their eyes, and observe the near photo-realism. The perspective is so perfect that you are transported into its depths, from the foreground tree, across the rippled reflections on the water, to the buildings and landscapes across the lake, and on up into the mountains. It’s an astonishing achievement. Because when you then walk closer, to observe the detailed knife and brush strokes and the physical texture, the image dissolves into what is almost Expressionism. Only the best Cubism similarly shimmers between near three-dimensional realism and pure abstraction. Little wonder some art historians say modern art begins with Cézanne.

Although a lifelong admirer of Delacroix, Cézanne allied himself, early in his career, with the Impressionists, especially Pissarro, and at first accepted their theories of color and their faith in subjects chosen from everyday life. Yet his own studies of the old master in the Louvre persuaded him that Impressionism lacked form and structure. He said: “I want to make of Impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums.”

In 2005, the Museum of Modern Art did a superb restrospective on the collaborative friendship of Cézanne and Pissarro.

Gardner continues:

His aim was not truth in appearance, especially not photographic truth, nor was it the “truth” of Impressionism, but rather a lasting structure behind the formless and fleeting screens of color the eye takes in. If all we see is color, then color gives us every clue about structure, and color must fulfill the structural purposes of traditional perspective and light and shade; color alone must give depth and distance, shape and solidity. Rather than employ the random approach of the Impressionists when he was face to face with nature, Cézanne attempted to bring an intellectual order into his presentation of the colors that comprised it by constantly and painfully checking his painting against the part of the actual scene–he called it the “motif”–that he was studying at the moment. When he said, “We must do Poussin over again, this time according to nature,” he apparently meant that Poussin’s effects of distance, depth, structure, and solidity must be achieved not by perspective and chiaroscuro but entirely in terms of the color patterns provided by an optical analysis of nature.”

The irony of Cézanne’s comment about the work of Nicolas Poussin is that Poussin is considered one of the masters of Seventeenth Century naturalism and classicism. His work can be seen here. But Cézanne had a paradigmatically different view of the meaning of naturalism.

Gardner:

To apply his methods to the painting of landscapes was one of Cézanne’s greatest challenges. The problems of representation were complicated by the need to select from the multiplicity of disorganized natural forms those that seemed most significant and to order them into pictorial structures with cohesive unity. Just as landcsape had been the principal mode of Impressionistic theory and experiment, so it became the subject for Cézanne’s most complete transformation of Impressionism. His method was to use his intense powers of visual concentration to observe the motif and its colors, sustaining the process of minute inspection through days, months, and even years. He resembled the contemporary scientist who proves his hypothesis with repeated tests. With special care, Cézanne explored the properties of line, plane, and color, and their interrelationships: the effect of every kind of linear direction, the capacity of planes to create the sensation of depth, the intrinsic qualities of color, and the power of colors to modify the direction and depth of lines and planes. Through the recession of cool colors and the advance of warm ones, he controlled volume and depth. Having observed that saturation (or the highest intensity of a color) produced the greatest effect of fullness and form, he painted objects chiefly in one hue–apples, for example, in green–achieving convincing solidity by the control of color intensity alone, in place of the traditional method of modeling in light and dark.

H.W. Janson summarizes:

When Cézanne took these liberties with reality, his purpose was to uncover the permanent qualities beneath the accidents of appearance. All forms in nature, he believed, are based on the cone, the sphere, and the cylinder. This order underlying the external world was the true subject of his pictures, but he had to interpret it to fit the separate, closed world of the canvas.

And to emphasize, here is Gardner:

Cézanne immobilized the shifting colors of Impressionism into an array of clearly defined planes that compose the objects and spaces in his scene. Describing his method in a letter to a fellow painter (Emile Bernard), he wrote:

Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, that is a section of nature…. Lines perpindicular to this horizon give depth. But nature for us men is more depth than surface, whence the need of introducing into our light vibrations, represented by reds and yellows, a sufficient amount of blue to give the impression of air.

And by reducing images to basic forms and planes, depicted with attention to their many sides, Cézanne here clearly was pointing towards Cubism. His abstract approach also clearly pointed towards what would become the various flavors of Expressionism.

Gardner:

By reducing the importance of subject matter, Cézanne automatically enhanced the value of the picture he was making, which has its own independent existence and must be judged entirely in terms of its own inherent pictorial qualities. In Cézanne’s works, the simplification of shapes and their sense of sculptural reliefand weight give a peculiar look of stable calm and dignity that is reminiscent of the art of the fifteenth-century Renaissance and has led modern critics to find in Cézanne some vestige of that ancient Mediterranean sense of monumental and unchanging simplicity of form that produced Classical art.

Ancient to Classical to Renaissance to Impressionism to Post-Impressionism, and pointing towards Cubism and Expressionism. And beyond that, his work is simply, powerfully, viscerally beautiful.

Now, let’s look at some photos of his hometown, Aix-en-Provence…

Although there are some wide boulevards, lined with cafes and restaurants, the center of the town consists of narrow, brightly painted streets…

And alleys…

And many large and small squares.

Cézanne’s biography can be traced by following these small street markers. The route includes all his family’s homes, his father’s businesses, the schools he attended, and other various places.

His father’s business, the Cézanne and Cabassol Bank, opened when he was nine.

14, Rue Matheron was the Cézanne family home from the time he was eleven until he was thirty-one.

At Ecole Saint-Joseph, he met his friend Henri Gasquet.

Many years later, he painted Gasquet’s portrait.

At the Bourbon College, Cézanne met his lifelong friend, the great writer, humanitarian, and political activist Émile Zola.

For several years, including while in law school, he took classes at the Municipal Art School.

At the church of Saint-Jean Baptiste du Faubourg, he married Hortense Fiquet. Later that same year, the church held his father’s funeral.

Cézanne sometimes hung out at Les Deux Garcons.

He mostly painted it from other angles, but Mont Sainte-Victoire was Cézanne’s mountain.

Maybe a ten minute walk outside the town centre was Cézanne’s atelier, where he worked for the last several years of his life.

His studio.

Never financially successful, and long separated from Hortense, he spent his last years in a small apartment, in this building, in central Aix. He died there, of pleurisy, on October 23, 1906.

Emile Bernard:

On Sundays we used to go to church. He would dress in his best clothes. He would sit in the factory pew and listen carefully to the sermon. As soon as he got to the little cloister before the Cathedral, he would be assaulted by beggars …He would prepare his money before leaving his room, and would dish it out in handfuls whilst walking past them.

“I’m having my share of the Middle-Ages,” he would whisper to me near the font. “I had seen Cézanne here, under the big painting of the Burning bush, in which Moses looks uncannily like him.”

His funeral was held at the Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur d’Aix, which was built in the 12th Century, and remodeled many times, over the centuries.

6 comments

Skip to comment form

I`ve not finished this marvelous essay, but hurried to make sure that one of your links can be fixed (if it`s not from my end).

The link to the portrait of Gasquet, brings up an error.

I tried it a few times. Other links are fine, so far.

I love the story leading into your discovery of this amazing artist.

Now, back to your essay.

of a lovely Impressionist exhibit I attended years ago with my mother at the AGO ( Art Gallery of Ontario), also in Toronto. I was never much for Impressionists but the exhibit despite crowds was quite lyrical and fulfilling.

beautiful essay

♥~