(noon. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

They say that even a broken clock tells the correct time twice a day (or at least it did back in the primitive analog era), and in his recent comment regarding the health care debate being Obama’s Waterloo, Senator DeMint (R-Mordor) proves “them” correct. DeMint is using the famed 1815 battle as an analogy for a loss in an epic final stand, and while this may be enough to make him appear “smart” in Republican “intellectual” circles, it turns out that upon further inspection, there’s actually some depth to the analogies that can be drawn from the scene of Napoleon’s final defeat.

So join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll take a hair-raising ride through Analogy-Land! See the president play the role of a French emperor, the Public Option as a well-defended farmstead, and we progressives as the Imperial Guard. The battle isn’t over, and we don’t yet (and may never) share their fate, but regardless, now is the time to learn what could’ve been done to alter the outcome of the fighting.

Any historical analogy that tries to match two wildly dissimilar events – say, social reforms at the beginning of the 21st century versus a titanic military struggle at the dawn of the 19th – is going to be fraught with dubious linkages and believability-stretching comparisons. This can’t be helped; indeed, it’s part of the fun of drawing analogies.

When it goes wrong, however – as when an analogy is based on a less-than-adequate historical understanding (note: clicking link provides a small amount of ad revenue to Faux”News”) – things can get ugly. In the linked opinion piece, Mr. Dan Gainor of the Media Research Center does little to expound on Senator DeMint’s earlier reference to epic defeat – rather, he simply throws out a couple of Wikipedia factoids on his way to complaining about the number of identified crises faced by the Obama Administration. He explains nothing about how Waterloo was won and lost, what the wingnuts should learn from the tactics and strategies employed, or even who is playing the role of Wellington in this grand anti-revolutionary struggle.

I think there’s more to the Waterloo analogy than the Republicans who want to use it as historical shorthand realize, but I don’t want to make the same mistakes they do. First, I’ll base my history on a fairly reliable source – in this case, the authoritative British Battles.com, with many first-person quotes lifted from the Wikipedia article – instead of a vague notion that the battle was between the French and “somebody else.” Next, I’ll ask us to dispense with the ideas that Napoleon was exceptionally short (he was not; like Rush Limbaugh’s recent trick of speeding up the tape in playbacks of Obama speeches so as to make the president’s voice sound small and juvenile, the British perpetuated the myth that the average-height Bonaparte was…ahem…quite small, actually) and that the French were “soundly thrashed” by Wellington. The duke’s own after-battle words belie this particular Republican/monarchist line:

It has been a damned serious business… Blucher and I have lost 30,000 men. It has been a damned nice thing – the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life. … By God! I don’t think it would have been done if I had not been there.

* Remark to Thomas Creevey (18 June 1815), using the word “nice” in its original sense of “uncertain”, about the Battle of Waterloo, as quoted in Creevey Papers (1903), by Thomas Creevey, Ch. X, p. 236. This has also been misquoted as “A damn close-run thing.”

Wellington’s Limbaugh-esque ego aside, the health care debate is a damned serious business, as well. There will be causalities, and scores to settle, when all is said and done. As on the field of battle, things will be done that cannot be undone, and cowardice before the enemy will take place in full view of one’s own army.

But this is the western way of war, as defined by von Clausewitz and enacted in the halls and chambers of our legislatures. We don’t generally seek out all-or-nothing melees; the method by which we fight is determined by strategy, positioning, and movement, until such time as the battlefield is ready and, at long last, the epic clash engaged. Rarely does this happen – indeed, there were gigantic battles that went essentially unfought during the Age of Enlightenment, when a general who realized he’d been outmaneuvered would simply march off the field (and suffer the resultant loss of face) rather than engage in what the textbooks indicated would be a defeat.

In the later wars of the Enlightenment, Napoleon was generally the guy doing the out-maneuvering. Like Obama, his combination of raw talent, perseverance, and charisma provided the grist for a meteoric rise from humble beginnings; what remains to be seen is whether or not the hubris that took root in – and eventually destroyed – the French emperor will similarly afflict our president.

Teachable Moment: The Escape from Elba and the Election of 2008

To make the Waterloo analogy work, we have to do a little stage-setting to establish context. I propose that we look at The Hundred Days (1 March – 18 June 1815, when Napoleon escapes from Elba and tries to re-establish his imperial rule) in terms of the Election of 2008. Prior to this, the role of Napoleon, at least in his “wrecker of nations” incarnation, was ineptly played by George W. Bush, who had broken his own army in a disastrously ill-advised invasion and had been driven from power as a result. Bush and the Republican ruling aristocracy are now relegated to the role of Louis XVIII, whose problems (in addition to morbid obesity, gout, and advanced age) would turn out to be considerable:

His concessions to the reactionary and clerical party of the émigrés, headed by

the comte d’ArtoisGlenn Beck andthe duchesse d’AngoulêmeLaura Ingram, aroused suspicions of his loyalty to the constitution, thecreation of his Maison militairewidespread use of overcompensated mercenaries alienated the army, and the constant presence ofBlacasCheney made the formation of a united ministry impossible.

The somewhat-truncated story of Obama-as-Napoleon picks up on the Mediterranean shores of France – or the State House steps in Springfield, Illinois – as an unlikely contender appears out of nowhere and threatens the established order. He marches north with a handful of his most dedicated soldiers, and The Establishment sends out an army to stop him. It’s touch-and-go for a while, but Obama successfully confronts those who stand astride the path to the capital, and incredibly, wins many of them over to his side.

Like the Republicans after the ’08 elections, Napoleon’s old enemies were forced into mounting a hasty, on-the-fly defense. While Louis XVIII fled to Belgium, Napoleon entered the capital and began reassembling his army from among those captured and released at the end of the emperor’s first reign (1800-1814). For us, this is similar to Obama reviving the fighting spirit in the Democratic Party, as he, too, called up a large force of highly motivated, but nevertheless green, troops to march under his banner.

Meanwhile, the forces of the status quo were assembling. They had not been ready for this and were caught out of position, but much as today’s rightwing noise machine knows well how the battle for public opinion is fought, so, too, did the alliance of British, Prussians, German states, and Dutch that formed the 7th (anti-Bonaparte) Coalition understand how to construct a defense on the fly. They elected to assemble in Belgium, which presented Napoleon with an opportunity: if he attacked quickly enough, he could split the allied forces and defeat them one by one, rather than facing the combined mass.

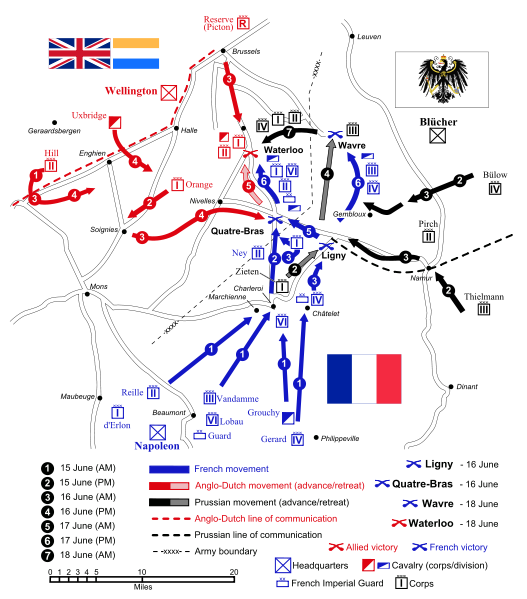

Teachable Moment: The Battle of Ligny and the Prussian Birthers

We can thus look (if we’re willing to grant the Moonbat a little allegorical license) at the progress made during Obama’s first hundred days as Napoleon’s march into Belgium. Like Napoleon, the president won a few critical strategic victories on the way to Waterloo – the Battle of Ligny (June 16, 1815), Napoleon’s last military victory (though one of his marshals won the Battle of Wavre on the same day as the defeat at Waterloo), did effectively split the Coalition forces and persuaded the Prussians to march off. Even though Field Marshal Michel Ney was unable to hold the crossroads at Quatre Bras, the Prussian loss at Ligny compelled Wellington to move north, where he assumed a defensive position on land he had personally reconnoitered the year before, near the town of Waterloo.

Since the bulk of Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher‘s army survived the encounter, and since the French were gathering for an attack on Quatre Bras, the Prussians were able to move off to the north, paralleling Wellington’s line of march and remaining in contact with him until he was in position to assist. For his part, Napoleon belatedly dispatched Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy to pursue the Prussians, and the late start, unclear orders, fuzzy decision-making, and supposition that the Prussians had moved off eastwards, towards home, left Grouchy miles away from the Waterloo battlefield exactly at the time when his boss needed him most.

Since the bulk of Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher‘s army survived the encounter, and since the French were gathering for an attack on Quatre Bras, the Prussians were able to move off to the north, paralleling Wellington’s line of march and remaining in contact with him until he was in position to assist. For his part, Napoleon belatedly dispatched Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy to pursue the Prussians, and the late start, unclear orders, fuzzy decision-making, and supposition that the Prussians had moved off eastwards, towards home, left Grouchy miles away from the Waterloo battlefield exactly at the time when his boss needed him most.

These Prussians are represented today by the Birthers, who have appeared as a distraction which threatens to pull vital resources away from the main battle. Like Grouchy, those of us who would follow and engage the Prussian Birthers face some perplexing orders – are we to bring them to a pitched battle, or simply keep them away from where the commander is dealing with the bulk of the enemy force? – and a competent, fast-moving adversary. Grouchy proved unable to rise to the task (or the Prussians proved too slippery); he was unable to close with them on the 17th, and when the fateful battle came, allowed the Prussians to link up with the Coalition left flank late in the day, thus assuring his emperor’s defeat. He’d failed to honor one of Napoleon’s maxims – always march toward the sound of the guns – and it cost him. Grouchy lived in exile in America until 1821, when he returned to something less than a hero’s welcome in France:

For many years thereafter he was equally an object of aversion to the court party, as a member of their own caste who had followed the Revolution and Napoleon, and to his comrades of the Grande Armée as the supposed betrayer of Napoleon.

He went on to get most of his honors back, but he remains an excellent example of how One Bad Day can ruin an entire career.

The Moral of the Story: Keep the Birthers away from the health care debate, don’t let them link up with the extreme fringe of the main Republican body, and remain close enough to the field of battle to provide support when the time comes. And don’t be Grouchy.

Teachable Moment: Know Your Enemy

A torrential rain on the night of the 17th abated by the morning, but Napoleon judged that it had left the field too soggy for movement of men and artillery. He was more than a little nonchalant, especially regarding his adversary – Waterloo was the first and only time Wellington and Napoleon faced off on the same battlefield. Several of Napoleon’s marshals, however, had fought against Wellington in the Peninsular War, and one of them (Soult) had enough respect for the duke formerly known as Lt.-Gen. Sir Arthur Wellesley that he suggested Grouchy be recalled. Napoleon reportedly sniffed,

“Just because you have all been beaten by Wellington, you think he’s a good general. I tell you Wellington is a bad general, the English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast.”

He displayed a similar lack of respect for the Prussians. When he was informed that a waiter in a nearby town had heard British officers saying that Blucher was prepared to march in from the nearby town of Wavre, Napoleon declared that the Prussians would need at least one more day to re-organize themselves after the defeat at Ligny – and besides, Grouchy would keep them from ever getting to the field anyway.

Wellington seemed to share at least part of Napoleon’s assessment, referring to his own force as

“an infamous army, very weak and ill-equipped, and a very inexperienced Staff”.

Numerically, the two sides on the road to Brussels that morning were more or less evenly matched: though Napoleon had more heavy cavalry and artillery pieces than the allies, once tallied with the Dutch and the contributions from the German states of Brunswick, Hanover, and Nassau, Wellington sported around 68,000 troops to Napoleon’s 72,000. You’d think the slight advantage would go to Napoleon, but that would mean you’d forgotten about the 50,000 Prussians who were gathering a scant 8 miles away.

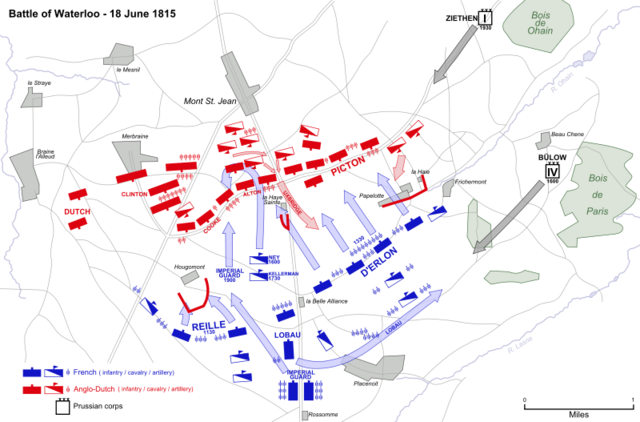

Napoleon thought Grouchy would be holding Blucher at bay (or something), and so devised his plan of attack based on what he could see of Wellington’s forces. The duke was a master at hiding his troops on the reverse slope of a hill, his numbers not becoming apparent until the enemy was too close to disengage; he pulled this same stunt at Waterloo, placing the bulk of troops at his center. Napoleon positioned his men evenly across the field, with the farms of Papolette and Hougoumont anchoring his right and left, respectively. Napoleon initiated the battle around 11 AM with a bombardment of Hougoumont, followed by an attack (led by Napoleon’s brother Jerome) on the farm around noon.

The Moral of the Story: Understand that even though the Republicans are split into multiple camps, they remain in contact – and within supporting distance – of one another. Probably more importantly: never underestimate the enemy, and don’t ever get cocky.

Teachable Moment: Hougoumont Farm as the Public Option

Hougoumont Farm was the key to Wellington’s right; if it was lost, the French would be able to move to encircle the British, or at the very least, do a lot of damage attacking from the exposed right flank. The farm itself was comprised of several buildings, a walled courtyard, an orchard, and a sunken lane running to the north, which allowed Wellington to deploy reinforcements without exposing them to a march across the artillery-dominated fields. Around the farm, Wellington deployed a relatively small number of troops – mostly Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards, though eventually 21 allied battalions (around 12,000 soldiers) were sent into the fighting which, once begun, lasted all day.

The French, who had initially thought Hougoumount would be a drain on British resources rather than their own, wound up deploying a lot more troops trying to take the farm than they’d initially intended. By the end of the day, the fighting had sucked in nearly an entire corps of infantry (33 battalions; +/- 14,000 men), a lot of cavalry, and the resources of many of his cannon. Napoleon’s diversionary tactic thus backfired; Wellington, who later remarked on the importance of holding the farm

The French, who had initially thought Hougoumount would be a drain on British resources rather than their own, wound up deploying a lot more troops trying to take the farm than they’d initially intended. By the end of the day, the fighting had sucked in nearly an entire corps of infantry (33 battalions; +/- 14,000 men), a lot of cavalry, and the resources of many of his cannon. Napoleon’s diversionary tactic thus backfired; Wellington, who later remarked on the importance of holding the farm

“the success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont”

was forced to commit resources he could have used elsewhere, but with the Prussians now beginning to arrive on his left, he was able use the site’s natural defenses to his advantage – ensnaring Napoleon in his own trap.

The Moral of the Story: The Public Option is a key position on this battlefield; take it, and the enemy’s flank crumbles. Failure to overwhelm the defenders arrayed within and around the admittedly difficult-to-take objective will result in a steady depletion of our forces, and could ultimately cost us the battle. Having transmitted this as one of our primary objectives, we must now commit to taking and holding the Public Option farm – and in so doing, we’ll turn the enemy’s flank, and the day will be ours.

Teachable Moment: Having Your Pieces in the Right Places

With his left now engaged against Hougoumount, Napoleon drew up his Grand Battery of 80 cannon at his center, and had them start firing at long range sometime between 1150 and 1330 (sources vary; additionally, British and French clocks were set one hour apart). The soggy ground meant that the cannonballs weren’t getting much destructive bounce, the artillery was widely dispersed, and the range was too distant for accurate aiming, but body count wasn’t what Napoleon was after – in fact, what he wanted sounds suspiciously like “Shock and Awe:”

“to astonish the enemy and shake his morale”

Around 1300, the emperor saw Prussians on his right flank, 4-5 miles distant, and had Marshal Soult fire off a message to Grouchy, telling him to come to the field attack them as they arrived. Regrettably for the Empire of France and the reign of Napoleon I, the addressee didn’t get the letter until way too late – around 1800. At the time the message would have mattered, Grouchy, though reminded by a subordinate that one always marches toward the sound of the guns, chose to follow Napoleon’s earlier orders to “keep the sword at (Prussia’s) back” and to engage the Prussian force at Wavre. By doing so, he hoped to interdict Blucher’s lines of support and communication; what he wound up doing instead was tying down his 33,000 men fighting half that many in a far-off battle of little strategic importance.

The Moral of the Story: Make sure subordinates know what they’re supposed to do, including contingencies. You can personally do everything right, but if you’re dependent on everyone acting as part of a concerted front – and in the health care debate, we are – then everyone needs to know enough about the grand vision to be able to see through the fog of war. Finally – and this should go without saying – don’t get suckered in to commit vast resources to fight skirmishes on the periphery of the main battle.

Teachable Moment: Beware the Entitled Cavalry

Meanwhile, back at the main engagement, the French infantry was advancing on the left and at the center, and having some pretty substantial success. The farm at La Haye Sainte, forward of the middle of the British lines, had been surrounded, and Wellington’s left began to waver. Cuirassiers, the last armored cavalrymen in Europe, had cut to ribbons a Hanoverian battalion sent to reinforce La Haye Saint, and even though Wellington still had plenty of fresh troops laying down on the opposite side of a ridge to avoid the French cannon, the Brits were feeling a bit hard-pressed.

It was at this point that the British cavalry decided to makes its presence known on the field – and there wasn’t much Wellington could do about it. Because it was widely suspected in England that this would be the last chance for a young man to win battle honors for quite some time, many political appointees – staff officers and cavalrymen, mostly – were foisted upon the commander by the Duke of York. Among these was Henry Paget, the Earl of Uxbridge, who had engaged in an affair with Wellington’s sister-in-law that resulted in his brother’s divorce. Wellington didn’t have much use for Uxbridge, but not much power over him, either. Uxbridge was thus given carte blanche, and he exercised it now, with a full-blown charge down the hill at the advancing French. Wellington might have anticipated such a hotheaded move:

Our officers of cavalry have acquired a trick of galloping at everything. They never consider the situation, never think of manoeuvring before an enemy, and never keep back or provide a reserve.

The British cavalry cut a huge swath through the French center, then decided to charge even further, toward the artillery at the rear. It wasn’t the best of tactical decisions – the cavalry had neither the time nor the capability to spike or spirit off the weapons – and many of his men died in the French cavalry’s counter-attack, but it did disrupt things and cost Napoleon valuable time. By the time it became apparent that the first infantry assault had failed, he had been forced to deploy the last of his reserves (save the fabled Imperial Guard) to hold back the Prussians, who were now appearing in force on Napoleon’s right.

The Moral of the Story: The British cavalry are the talking heads of the right-wing noise machine. They are not beholden to any single commander, and they will run hither and thither on the field, causing mayhem with no thought to holding the ground they overrun. They can (and must) be dealt with, but only with the understanding that time is against us – and that the most effective defense against cavalry is a tight square of infantry, bristling on four sides with a hedgerow of bayonets..

Teachable Moment: Judging When the Time is Ripe

Marshal Ney saw, from his position at the French center, movement behind the British lines. Whether these were wounded being evacuated or prisoners being escorted to the rear doesn’t really matter: Ney thought the Brits were giving up their position. Seeking to press the advantage, he launched a full-scale cavalry assault, neglecting to take the time to bring his infantry and artillery with him.

This was an important oversight, for over the preceding few centuries, tactics had developed in such a way that each type of unit enjoyed checks and balances vis-à-vis the others. Thus, artillery was vulnerable to cavalry, so it was protected by infantry. Infantry is vulnerable to cavalry unless it forms one of the aforementioned squares, which themselves are vulnerable to infantry or artillery attack. The long and the short of it is: Ney didn’t have the right troops coming up behind him to either burst through the British squares, or to hold the ground his charging cavalry captured.

That wasn’t all he didn’t have with him: according to some sources (and contrary to standard practice), Ney’s troopers didn’t bring with them the headless nails they’d need to “spike” captured enemy guns. When a British counterattack forced the French cavalry to retreat, the guns were in perfect operational order to open up on the advancing French infantry. Had Ney spiked the guns, far more of Napoleon’s soldiers would have made it to the top of the ridge – possibly even enough to have pushed Wellington off the field.

It wasn’t until several hours of cavalry charges had passed that Ney finally brought up his artillery and launched a proper combined-arms attack. At this point, it was too late: the advance was stopped with another Uxbridge-led charge of heavy cavalry, but the constant pressure on the center had caused Wellington’s flanks to weaken, especially on his left.

The Moral of the Story: The first time Ney charged, it was too early and without proper support; the second time, it was too late and the enemy was ready. I don’t know exactly when the right moment will come to launch the attack that will rout the adversary from the health care field, but that’s why we’ve got well-trained and highly motivated leaders – our task will be to remember that Napoleon did, too, and that even our most talented leaders won’t always make the right choice.

Teachable Moment: The Attack From the Flank

La Haye Sainte fell into French hands, but although Napoleon didn’t know it yet, that victory came too late: the Prussians were now on the field. Frederick Bulow‘s IV Corps had arrived at Plancenoit and was seriously pressing the French right, so much so that Napoleon committed the last of his non-Imperial Guard reserves to shoring up its defense. This was successful, and Napoleon turned his attention once more to La Haye Sainte and the center of Wellington’s lines.

The Moral of the Story: We have to watch our flanks. As we have been reminded on numerous occasions, the wingnuts will not base the movement of Overton Windows to the far right on facts, reality, or anything else inconvenient to their worldview. They will hit us hard, from the right, and though our best move is to interdict them before they get to the battlefield, second-best would be keeping them pinned down on the fringes.

Teachable Moment: Going for Broke

The emperor had no forces left to send in but the hitherto-undefeated Imperial Guard, and about 4000 of these he led personally up to La Hay Sainte. Far from a small cadre of bodyguards, the Guard was an army within an army, complete with its own cavalry and infantry units. Napoleon chose to assault the British lines with infantry of the Middle Guard, which left plenty of soldiers of the Old Guard to die heroically covering the upcoming retreat.

The emperor had no forces left to send in but the hitherto-undefeated Imperial Guard, and about 4000 of these he led personally up to La Hay Sainte. Far from a small cadre of bodyguards, the Guard was an army within an army, complete with its own cavalry and infantry units. Napoleon chose to assault the British lines with infantry of the Middle Guard, which left plenty of soldiers of the Old Guard to die heroically covering the upcoming retreat.

Napoleon split his forces into a three-pronged attack up the ridge. Two of the Guard columns acquitted themselves well before having their flanks fired into and suffering an advance-stopping bayonet charge; the third, seeing the misfortunes of the first two, broke and ran. This had a debilitating effect on every Frenchman who could see it happening – nothing saps an army’s will to fight like hearing this about its most storied soldiers:

“La Garde recule! Sauve qui peut!” (“The Guard retreats! Save yourself if you can!”)

Some of the Guardsmen attempted to bring some order to their retreat by assembling south of La Haye Sainte, but they were scattered before Wellington’s army, which was obeying the general’s waving-hat gesture meaning “general advance.” Those Frenchmen whose faith in the Guard wavered in the initial phase of the retreat might have been heartened to hear some of the Guard, having been offered a chance to surrender, reply,

“La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas!” (“The Guard dies, it does not surrender!”

The Moral of the Story: When to send your best troops into the fray is another of those matters best left to the professional leaders, who can hopefully see the bigger picture. It should be noted that while the deployment of the elite forces can result in momentary spikes in morale among the rank-and-file, the downward plunge which accompanies seeing those elite troops in headlong retreat may not be worth risking their defeat.

Teachable Moment: What You Leave Behind

Napoleon moved back to La Belle Alliance Inn, which had served as his headquarters for much of the day. There he hoped to rally the French behind his personal bodyguard: two battalions of Old Guard, formed in squares on either side of the inn. Napoleon took command of the square on the left, but was unable to begin regrouping his forces before the British and Prussians were upon them. The squares withdrew in relatively good order, but the rest of the French army was broken. Cavalry harassed the retreat until around 2300, in the process capturing Napoleon’s baggage train and a clutch of diamonds – jewels which later adorned the crown of King Friedrich Wilhelm. Ney described the final French movements away from the field:

There remained to us still four squares of the Old Guard to protect the retreat. These brave grenadiers, the choice of the army, forced successively to retire, yielded ground foot by foot, till, overwhelmed by numbers, they were almost entirely annihilated. From that moment, a retrograde movement was declared, and the army formed nothing but a confused mass. There was not, however, a total rout, nor the cry of sauve qui peut, as has been calumniously stated in the bulletin.

The carnage was, of course, incredible. The French lost 25,000 KIA/WIA, with another 8000 captured; the allies suffered around 22,000 casualties – numbers reflected in this description of the site a few days later:

(June 22) I went to visit the field of battle, which is a little beyond the village of Waterloo, on the plateau of Mont St Jean; but on arrival there the sight was too horrible to behold. I felt sick in the stomach and was obliged to return. The multitude of carcasses, the heaps of wounded men with mangled limbs unable to move, and perishing from not having their wounds dressed or from hunger, as the Allies were, of course, obliged to take their surgeons and waggons with them, formed a spectacle I shall never forget. The wounded, both of the Allies and the French, remain in an equally deplorable state.

–Major W. E Frye After Waterloo: Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819.

With the full force of the allies marching on Paris, Napoleon announced his second abdication on June 24, less than a week after Waterloo, though he didn’t surrender until July 15 (he may have been trying to escape to North America, but the British were blockading the French ports). In October, 1815, Napoleon was exiled to the Middle of Nowhere: St. Helena, a tiny island in the South Atlantic in between Africa and South America, and he never posed a threat to civilization again. He died (? – q/v. Monsieur N.) in 1821, ostensibly of stomach cancer, though theories that he was slowly poisoned by his captors have also been advanced.

With the full force of the allies marching on Paris, Napoleon announced his second abdication on June 24, less than a week after Waterloo, though he didn’t surrender until July 15 (he may have been trying to escape to North America, but the British were blockading the French ports). In October, 1815, Napoleon was exiled to the Middle of Nowhere: St. Helena, a tiny island in the South Atlantic in between Africa and South America, and he never posed a threat to civilization again. He died (? – q/v. Monsieur N.) in 1821, ostensibly of stomach cancer, though theories that he was slowly poisoned by his captors have also been advanced.

The Morals of the Story: 1. Max Baucus and the Blue Dogs are the faltering Imperial Guard; if they break, the entire army could follow. We can’t allow ourselves to be suckered in by Wellington’s hide-behind-the-ridge trick, and we’ve got to keep pouring on the fire to give spirit to our wavering advance troops.

2. We’re at war, and there are going to be casualties. There are going to be things said that can’t be taken back, lines that, once crossed, cannot be un-crossed – and the sooner we recognize that health care reform is a partisan, winner-take-all fight to the death, the better off we’ll be at repelling an adversary who already regards it as such.

3. Whether you chose them or not, losing certain battles can have the result of being exiled to remote islands in the South Atlantic – or its modern political equivalent.

Historiorant

There is perhaps one final analogy to be beaten from this way-dead horse: that of the decorations and name-changes that were awarded the various regiments which fought at Waterloo. The 1st Foot Guards, for example, were thought to have beaten back the Grenadiers of the Old Guards, so their regimental name was upgraded to “Grenadier Guards,” and their uniforms modified to include a grenadier’s bearskin hat. Ditto the Household Cavalry, which adopted the cuirass to honor themselves for beating the French cuirassiers, and the fact that just about every European army noted how effective were the lancers of Napoleon’s light cavalry, and converted their own to lancers within a few years.

There is perhaps one final analogy to be beaten from this way-dead horse: that of the decorations and name-changes that were awarded the various regiments which fought at Waterloo. The 1st Foot Guards, for example, were thought to have beaten back the Grenadiers of the Old Guards, so their regimental name was upgraded to “Grenadier Guards,” and their uniforms modified to include a grenadier’s bearskin hat. Ditto the Household Cavalry, which adopted the cuirass to honor themselves for beating the French cuirassiers, and the fact that just about every European army noted how effective were the lancers of Napoleon’s light cavalry, and converted their own to lancers within a few years.

The most optimistic among us might look at these examples and say, “hey, well, at least something of the defeated survived,” and maybe it’s true – maybe a watered-down public option with a start date a decade from now does speak to the ages somehow. It might be better, however, if we didn’t regard this battle in terms of which tokens will survive…

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

a little ABBA:

Although I sort of see the combatants as reversed; with a splintered coalition of pro-reform forces fighting a desperate rearguard action against a ruthless and haughty adversary who has nothing to lose.

And after all, didn’t Napoleon say about Wellington pinning himself to the (public option) hilltop:

This was a joy to read. I’m sure your aware of the Cambronne (the commander of a battalion of the Old Guard who was to make the stand allowing Napoleon to flee) controversy. The fact that most who were there during the last stand of the guard did not hear “La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas” but “Merde!” The more gallant statement is more than likely an invention of french historians. Somehow I think Cambronne in that situation was much more likely to have gone with the more colloquial term. And “merde” is a more appropriate term for where we are now with health care reform, don’t you think?

Excellent work! You are a treasure.