(noon. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

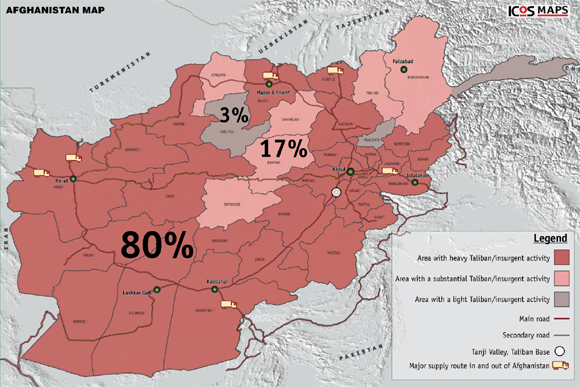

The CS Monitor reports the Taliban is now operating in 80 percent of Afganistan. “Long considered one of the most stable and peaceful parts of the country, the northern provinces have seen rising violence as heavy insurgent activity has spread to 80 percent of the country – up from 54 percent two years ago.”

The article cites a recent map from the International Council on Security and Development (ICOS). The ICOS map is based upon data “gathered from daily insurgent activity reports between January and September 2009”. The ICOS believes their assessment is “conservative”.

|

The U.S.-led coalition already has more troops and contractors in Afghanistan than the Soviets did at the height of their occupation.

As others have noted, Gen. Stanley McChrystal is expected to ask for more troops be deployed in Afghanistan. The NY Times reported McChrystal is likely to present President Obama with three options:

The smallest proposed reinforcement, from 10,000 to 15,000 troops, would be described as the high-risk option. A medium-risk option would involve sending about 25,000 more troops, and a low-risk option would call for sending about 45,000 troops.

Will sending 45,000 additional troops make a difference?

If not, how many troops would actually be needed in Afghanistan? Experts writing papers for the U.S. military put the counter-insurgency troop levels at 20 soldiers per 1,000 inhabitants or a 1:50 ratio for calculating troop density.

According to a 2006 paper, “Boots on the Ground: Troop Density in Contingency Operations” (pdf), written by John McGrath and published by the U.S. Army, it is generally though that 20 solders per 1,000 inhabitants is “the minimum effective troop density ratio” for a counterinsurgency campaign.

While there are no established rules for determining troop density, since 1995 several military observers, analysts, and civilian journalists have promulgated general theories on troop density. Most theorists generally cite historical precedent when proposing ratios for troop density levels. Most density recommendations fall within a range of 25 soldiers per 1000 residents in an area of operations (1 soldier per 40 inhabitants) to 20 soldiers per 1000 inhabitants (or 1 soldier per 50 inhabitants). The 20 to 1000 ratio is often considered the minimum effective troop density ratio.

Gen. David Petraeus would agree. In the “FM 3-24 – Counterinsurgency” (pdf) manual coauthored in 2006 by him with Gen. James Amos, that same 20:1000 ratio is cited.

The movement leaders provide the organizational and managerial skills needed to transform mobilized individuals and communities into an effective force for armed political action. The result is a contest of resource mobilization and force deployment. No force level guarantees victory for either side. During previous conflicts, planners assumed that combatants required a 10 or 15 to 1 advantage over insurgents to win. However, no predetermined, fixed ratio of friendly troops to enemy combatants ensures success in COIN. The conditions of the operational environment and the approaches insurgents use vary too widely. A better force requirement gauge is troop density, the ratio of security forces (including the host nation’s military and police forces as well as foreign counterinsurgents) to inhabitants. Most density recommendations fall within a range of 20 to 25 counterinsurgents for every 1000 residents in an AO. Twenty counterinsurgents per 1000 residents is often considered the minimum troop density required for effective COIN operations; however as with any fixed ratio, such calculations remain very dependent upon the situation.

So if the 20:1000 (1:50) ratio is used, how many troops would need to be deployed to Afghanistan?

The CIA estimates Afghanistan’s population at 33,609,937 people as of July 2009.

So following a 1:50 ratio would require the U.S.-led coalition force size to be at approximately 672,200 troops.

Since such “calculations remain very dependent upon the situation”, I think with the Taliban being active in 80 percent of the country with the U.S.-led coalition only providing security in 3 percent of the country, this level may be conservative of the actual Western troop levels that would be needed in Afghanistan. And since counterinsurgencies are not quick operations, such a force level would likely need to be maintained for years to come.

And if the bordering region with Pakistan is considered when making a force size calculation, then the required force size would undoubtedly increase. According to the CIA estimate, Pakistan’s population as of July 2009 was at 176,242,949 people.

Can McChrystal explain why 45,000 troops more, at most, will make a difference in Afghanistan?

I think the reason why McChrystal’s request will be small, is that the military and the hawks in the Obama administration do not believe the American people would support a massive troop deployment that the military’s own counterinsurgency manuals suggest is needed. So instead there will be some who will continue to to keep the escalation in Afghanistan going on the sly at a trickle of a few thousand of troops every 4-6 months. This, I think, would be an enormous LBJ-like mistake if Obama chose this course.

Therefore, I think if the military cannot come clean with the American people with how many troops are actually needed in Afghanistan to achieve the objectives the Obama administration has set, then the president must admit these goals are unobtainable and order a withdrawal. Because if this truly is, as Obama says, a “war of necessity,” then should he not treat it as such?

I hope Obama is wise enough not to get locked into a policy slow escalation of troops in Afghanistan. If he should order a withdrawal or, worse order a 500,000 plus troop increase for Afghanistan, I think it will be important for the country to remember the Bush administration was never serious about waging a war in Afghanistan.

Then-Defense War Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was a proponent of the use of a small military force to achieve a quick victory and then were dependent on outside military contractors. In 2006, Carl Robichaud of the Century Foundation wrote of the failings of the Rumsfeld Doctrine:

Afghanistan was the laboratory for this new notion of warfare and national power. Rumsfeld’s Pentagon wanted to demonstrate that small groups of ground forces combined with overwhelming air power could win wars – in theory, a useful approach because it limits American casualties and costs.

The doctrine’s failures in Iraq are well documented. But its shortcomings in Afghanistan have received less attention because the unraveling has occurred in slow motion and with scant media attention.

The Taliban were routed by small teams of Special Forces, who directed devastating airstrikes and guided their Afghan allies on the ground. But victory was never achieved. America’s Afghan proxies allowed Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden to slip away and reestablish their operations in Pakistan. The Taliban were driven out, but were never disbanded or politically reintegrated, and their reconstituted forces, drawing from the Iraq playbook, have made this the bloodiest year yet.

Of course we will never know what would have happened if the war in Afghanistan had been handled differently: if America had taken up NATO’s Article 5 declaration (“an attack against one is an attack against all”) in earnest and led a genuinely multinational force; or if the expanded coalition had deployed 200,000 troops, rather than 20,000, and stabilized the whole country, rather than just Kabul; if peacekeepers from Muslim nations had been enlisted; if ground troops were in place to cut off Mr. bin Laden’s escape; or if the 5th Special Forces Group had been permitted to continue its hunt for bin Laden, rather than being redeployed to prepare for Iraq.

Even through 200,000 NATO troops in 2001 may not have been enough to secure Afghanistan for the long term according to the 1:50 suggested ratio. I think we will never know what success is in Afghanistan because Bush and Rumsfeld set firm the war’s eventual outcome in 2001 by following the Rumsfeld Doctrine.

Admiral Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said last month that the United States is “starting over” in Afghanistan and some in the administration may wish to resetting the clock. This is impossible because the Afghans are not going to forget the past eight years of war.

The sooner we acknowledge we went to war with the administration we had, did our best, and now is the time to declare victory and start bringing the troops home. Sending more troops to Afghanistan now is only compounding the original mistake. In war there is no reset button.

Cross-posted at Daily Kos.

31 comments

Skip to comment form

let’s send them!

Every one is located in a deep red zone.

Not good. Not good at all.

Not a problem with trainers, but our combat troops need to come home.

Warmest regards,

Doc

Cut out the middlemen and drug/war lords. Bring ALL the troops home and send in the Peace Corps. Use the savings to build schools, hospitals and infrastructure. Kill them with love and kindness. Probably cost less than ten cents on the dollar and everyone outside of the drug/war lords, the MIC and the Establishment would be happy.

Never happen. It’s too sane and humane.

is the day you leave.

in Vietnam and that asshole escapee from a condom Henry Kissinger who said it. The very same Henry Kissinger who founded Kissinger Associates who begat David Rothkopf and the other band of globalist assholes who mention Alex Jones for daring to challenge the paradigm of global exploitation.

did you watch Bill Moyer’s last night? A fascinating interview with Nancy Youssef on Afghanistan

We talk about Afghanistan as an eight year war. But the truth is, it’s been eight separate, individual years of war.”

All this leaves U.S. and NATO soldiers with a host of ambiguous choices. Youssef says they are faced with questions like should they “train the soldiers to serve a corrupt government that we’re not sure we can put faith in? Stabilize a country against the Taliban that some residents are comfortable or at least accept in their communities?”

Youssef perceives a disconnect between what both Presidents Bush and Obama have called a “war of necessity” and the way the war has been handled thus far: “What’s happening now in Washington and all these assessments – we’re trying to answer very basic questions: ‘What is the goal? What is the strategy? How do you implement the strategy?’ So, even though we call it a war of necessity, I don’t think it’s ever been treated as a war of necessity, even now. That debate is just starting, in year eight of the war. It’s extraordinary.”

watch the video,