(11 am. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

A strategist at the Deutsche Bank had something interesting to say last week regarding the economic crisis in southern Europe.

“The problems currently faced by peripheral Europe could be a dress rehearsal for what the U.S. and U.K. may face further down the road,” Jim Reid, a strategist at Deutsche Bank in London, wrote in a research note today.

It seems impossible that what is going on in Greece has anything to do with America. After all, Greece has defaulted on its debts so often over the last two centuries that you could almost set your watch to it. It was always contained in the past because Greece’s economy is so small, so why would this time be different this time?

And yet, it isn’t contained this time. It is spreading and no one knows how far it might go.

Contagion: The likelihood of significant economic changes in one country spreading to other countries. This can refer to either economic booms or economic crises.

The first time the term “Tequila Effect” was used in reference to economics was after Mexico defaulted on its foreign debt in August 1982. In response, international banks stopped lending to all of Latin America. The result was a currency and fiscal crisis from the Rio Grande to Patagonia and everywhere in between.

What did Argentina have to do with Mexico other than both speak Spanish? Nothing. That’s how contagion works. It doesn’t have to make sense. There are only two emotions in the markets – fear and greed. Both of those emotions can overcome reason and logic in a split second. Both of these emotions are self-reinforcing.

Contagion tends to happen in periods of economic stress. When Austria’s largest bank, Creditanstalt, went bankrupt in 1931 its effects swept around the world. Within a few weeks Britain was forced off the gold standard and credit dried up to Wall Street banks. The event turned an economic downturn into the Great Depression.

The best example of contagion is also the most recent – the 1997 Asian Currency Crisis. On July 2, 1997, Thailand was forced to devalue its currency.

It didn’t get much news coverage because Thailand’s economy was so small (GDP around $500 billion). But the financial markets noticed, and panicked in spite of the fact the global economic condition was relatively strong at the time. Within a few months hundreds of millions of working class people were suddenly thrust into poverty. The contagion kept spreading, like an organism seeking out a weak host. It eventually claimed the economies of Russia and Argentina, even though they had absolutely nothing to do with Thailand.

Which brings us back to Europe. Contagion usually takes the form of a flight of capital.

This is what happened in Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998, and what is happening today in Greece.

A staggering €8bn-€10bn (£7bn-£8.7bn) may have been taken out of Greece by private investors since it became engulfed by economic turmoil in November.

“In the last four to six weeks a lot of money has been moved abroad; I’ve heard extraordinary figures,” analyst, Kostas Panagopoulos said.

“People are moving funds either because they don’t trust our banking system, want to avoid what they fear will be taxes on deposits or are simply anxious about the future of our economy.”

Like Thailand, Greece has a relatively small economy (GDP $350 billion). Compared to the economies in the rest of Europe, its troubles shouldn’t be more than a nuisance. Yet Spain felt it necessary to point out the obvious last week.

“Spain’s situation is not like that of Greece, not in terms of public debt nor in terms of economic strength,” Ms. Salgado said in an interview with La Cope radio.

Spain’s economy has melted down as fast as Greece’s has, but it started from a far stronger position. Regardless, the markets are demanding far higher returns on loans to Spain than just a week ago.

Spain’s problem is that it is next door to Portugal.

Portuguese government bonds weakened Wednesday after the country’s debt agency sold fewer 12-month Treasury bills than planned at an auction as investors required sharply higher yields than at the previous auction two weeks ago in low volume demand.

What happened here was that Portugal suddenly yanked back on their bond sale, not because they didn’t need the money, but because if they had offered the full amount there may not have been enough buyers. That’s called a failed auction, and it usually happens right before a country defaults.

What all these countries have in common is that they are all PIGS. That’s the unpleasant term that the financial markets are using for Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. Being a member of this exclusive club has its disadvantages.

Fears of sovereign debt contagion across the eurozone sent European markets sharply lower on Thursday as negative sentiment spread to Wall Street with US markets also hit by worse than expected jobless data

European and UK stock markets fell more than 2 per cent, with Portuguese and Spanish stock markets leading the declines with falls of 5 per cent or more. Investors also sold sovereign debt in these periphery eurozone countries and sought the safety of the dollar and US Treasuries.

Reflecting those concerns, the western Europe Markit SovX index, which measures the cost of insuring against the risk of default, widened beyond 100 basis points for the first time amid heavy buying in the sovereign credit default swap market. CDS spreads on Portugal hit record highs, up 28 basis points to 222 basis points, while Greek credit default swaps rose 21 basis points to 412 basis points, heading closer to records of 421 basis points reached in January.

The most immediate concerns for the markets is domestic resistance to austerity measures. In Portugal it was parliament that defeated extreme cutbacks in social programs. In Greece, it is the looming threat of massive, and violent, strikes.

It should be noted that technically, the troubles didn’t start with Greece. They started when Dubai defaulted. It may or may not be a coincidence that the central bankers of the world are right now having a secret meeting in Sydney.

Representatives from 24 central banks and monetary authorities including the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank landed in Sydney to meet tomorrow at a secret location, the Herald Sun reports.

…

“This does feel like ’08 and ’07 all over again whereby we had these sort of little fires pop up and they are supposedly contained but in reality they are not quite contained,” said H3 Global Advisors chief executive Andrew Kaleel.

“Dubai should have been an isolated incident and now we are seeing issues with Greece, Portugal and Spain.”

Speaking of little fires, its a good idea to keep an eye on Latvia, a nation with the same population of Dubai. Since the global credit crisis started in 2007, Latvia’s economy has shrunk by 25% and is expected to shrink another 4% this year. Meanwhile, the IMF is demanding that the Latvian government cut its spending another 6%. This cannot continue much longer without a popular backlash.

The scale of this building sovereign crisis cannot be understated. Some are saying that it could make the Euro currency “unstable”. Unless it gets contained quickly we could be looking at the next leg down in a global margin call.

The EU’s refusal to offer Greece anything beyond stern words and a one-month deadline for harsher austerity – while admirable in one sense – is to misjudge how fast confidence is ebbing. Greece’s drama has already metastasised into a wider systemic crisis. The world risks a replay of the Lehman collapse if this runs unchecked, this time involving sovereign dominoes.

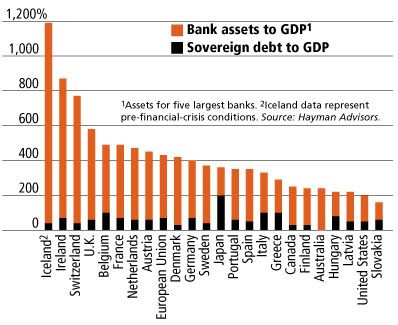

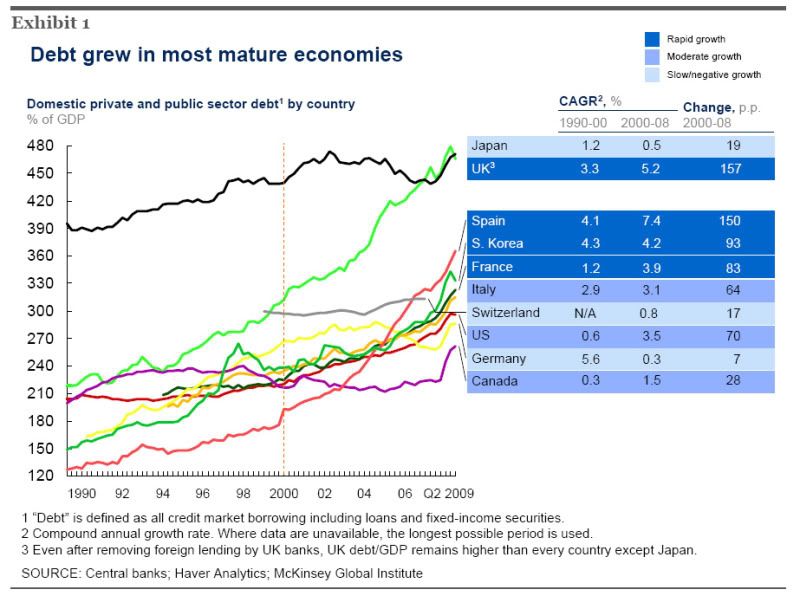

The scale matches America’s sub-prime/Alt-A adventure and assorted CDOs and SIVS of the Greenspan fling. The parallels are closer than Europe cares to admit.

At the very same time that this crisis is hitting, the bailouts of the world are ending. Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are about to cut off their quantitative easing. They aren’t alone.

It may seem counter-intuitive for the bailouts and stimulus to be cut right when a global economic crisis is building, but it isn’t. The sovereign debt crisis we are now witnessing is because of the bailouts. More deficit spending will just increase the financial pressure. What we are witnessing is a limit to the Keynesian solution.

12 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

a new sovereign debt crisis? This article at Baseline Scenario discusses the current EU economic crisis, and possible responses by the EU nations and/or IMF, and concludes that:

Well, thankfully, at least we have Palin’s antics at the Tea Party convention to distract everyone from this unfortunate set of circumstances.

… and they had bad drought and fires in the summer- more climate change problems.

50+ hours at work in 5 days, I’m in pain because of it, and my brain isn’t firing on all cylinders: I can barely add 2+2 at this point.

So I suspect I missed the finer points of your analysis (“contagion” I get. I think).

I don’t get the charts, though, and I really don’t quite understand what you mean here:

Deficit as % of GDP 2010= 10.64 (projected) (up from 3.24 in 2008)

Or–between Spain and Greece.

They went to the top companies. The auto bailouts actually encouraged outsourcing. The stimulus was badly thought out as well.

On top of that increase US military spending (which causes pressure on all other countries to spend as well, either defensively against the US, or because the US is forcing them to) is all debt as well.

The net result is more debt, stronger ‘too big to fail’ companies, but no jobs, increased global instability (when everyone has more military stuff, everyone fears their neighbor will use it-and someone will) .

So, now Obama wants to cut social services, but still increase military spending even more. And, the EU and IMF is putting huge pressure on Greece and Spain to cut social services too. Goldman Sachs’s president has been invited to Greece, in hopes GS would help sell Greece’s bonds, and told them do exactly that– or else.

Meanwhile Stiglitz went there, and told them the exact opposite–that more government social and job creation spending is the only way out of the woods.