(2PM EST – promoted by Nightprowlkitty)

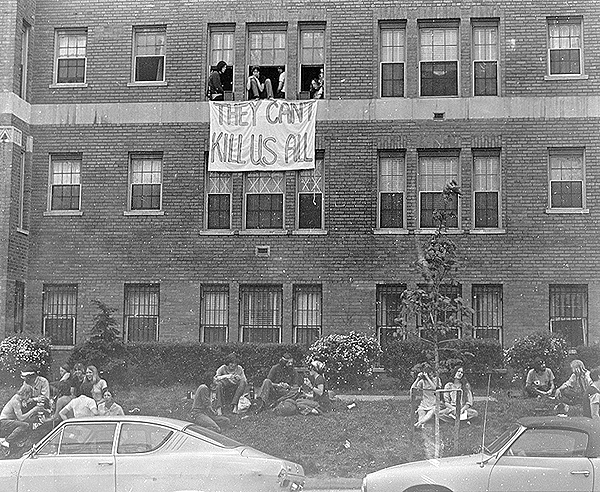

The sign was hung out of an NYU dorm window. It read, simply

I want to use that sign as a starting point in talking about some largely unsuccessful emotional archaeology I’ve been doing, trying to reconstruct what it felt like to be 20 years old and a revolutionary in the midst of the first national student strike the country had ever seen.

I know I wasn’t expecting to be killed, even though–forty days ago today-the Kent State murders were only two days in the past and in the forefront of everyone’s thoughts.

And that wasn’t what the dorm room sign was about. Those kids didn’t expect to be killed either. They were celebrating the fact that the scope of our movement, the hundreds of new campuses-including high schools-which had gone out on strike since May 4 had pretty much removed violent repression as an option for the ruling class. I quoted John Kaye on the intensity of those days in yesterday’s installment. I’ve recently spoken with Mirk and Mindy, who, like me, came out of NYU and we all agree that there is a lot, a surprising amount, from these intense weeks that we just don’t remember.

I put this down to three things.

First we were drinking deep of an emotional cocktail that combined rage, exhilaration and simple exhaustion.

Second, we were in an environment where all of daily life was changed. Classes, papers, tests no longer had claims on students’ time; though they might still worry about such things, as 12+ years of US schooling had trained them to, we were on strike! The struggle demanded that we do new things and do old things in new ways and do them all at once.

In the two or three days following May 4th, I am fairly certain that I spent many hours with kids from nearby Taft High School with whom NYU Uptown SDS had been working, helped them organize a walkout and lay out the second edition of Rip Off, their underground paper, and get it printed by the Kimball collective. The Uptown crew also met to develop programs we were demanding that the administration put in place to serve the West Bronx community. I also seem to recall spending much of my time downtown, centered around stints, including some quickly grabbed zzzs in the middle of the night, guarding the seized Courant computer. And meetings to coordinate activities on the Uptown and Washington Square campuses. Then there was the peace march on Wall Street that the hardhats attacked. And a bunch of us went to City College to support the students there. And…

Third, was the simple fact that we had entered uncharted terrain. The enemy was in retreat, though still deadly. We were, in chaotic fashion, advancing. What should we be demanding-of our school, of the government, of society?

For instance, to return to my touchstone. our SDS chapter had a standing demand that NYU enact an open admissions program for community residents who graduated high school. It was a damn good program, written by some guy named Mike a year or so earlier (we lost track of him when he transferred out), but it had never been anything we had the power to make the administration deal with.

Now things were different, even if the majority of students who were on strike weren’t ready to go as far as open admissions–concerned what it might do to the value of their diplomas and to tuition rates. Should we do more education to win our classmates over? Set up our own free tutoring programs for grads from Taft and other local high schools to prove to the administration it could work? Force the NYU administration to develop partnership programs with the city officials running those high schools and start taking the first steps?

Lacking experience, absent central coordination, without tested leadership to help us sort through the options, we tried everything, usually without a clear plan and goals.

I’m not sure how different things could have been, given the historical circumstances, but I guess the reason I am writing this multi-part reflection is to identify and salvage some of the lessons of May. ’70, so when history puts something like it on our plate again, we can avoid some of the old mistakes, and make some new ones as we move forward.

6 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

First, this post, is by virtue of its subject matter, a little less coherent that most of the previous seven (findable by the simple expedient of clicking on my name).

And it was originally posted at Fire on the Mountain yesterday, but I had to rush to my deejay gig in Brooklyn before I had a chance to get it up here.

Sorry, all…

of being part of movement that included violent push back.

Their sign reminds me of a song that I heard first in high school by this band from Kansas, called Coalesce.

I’ve been reading and remembering.

The person who’s come up the most for me, somebody I didn’t meet until later on, but who was at NYU Washington Square and later for masters law work at the Law School, who was a helluvan organizer and lawyer and Radical, with a capital R, is my old, but now departed friend, Gerry Dunbar (1947-2007).

Thanks for such evocative essays.

I don’t think there are many lessons we can take from that era. It was more than 40 years ago–it seems like centuries. One thing we can take that is very important and was foremost on my mind at the time: to build alternative institutions–this was not done at the time nor was there much interest in it. The opinions and instincts many of us had were barely skin deep and would later change to an obsession with the culture of narcissism and its artifacts like big houses, big cars, wine, gourmet food, cocooning and so on.

What we lacked were elders and leaders; there were some but few and far between and without them we were picked apart and the “new left” never recovered. Never even came close to recovering. It deflated gradually in the 70’s and quietly expired in the 80’s.

Whatever we have or don’t have is new and has to be built and nurtured anew. The old underpinnings are gone. Young people care very little for large issues–prefer, in general to let the authorities handle everything. Courage is something that many of us did feel was a good thing–don’t think many think so now.