(10 AM – promoted by TheMomCat)

‘Tis the time of the season here in the Bluegrass for fireflies (or, as we used to call them at home in Arkansas, lightening bugs). Fireflies are an amazingly large group of insects, and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

The experts still can not agree how to categorize them systematically, so we will just touch on their classification. It is important, however, to place them within the insects at least to a zero order approximation.

I got to thinking about them the other night when my dear friend and her little girl were in their yard next door trying to catch the few that were already flying. Next week it is supposed to be warmer, so the three of us may be able to spend some quality time together catching them, and letting them go, of course, after The Little Girl goes to bed.

Let us go ahead and do the taxonomy thing, then we shall get to more interesting topics. Here is the hierarchy:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Coleoptera

Suborder: Polyphaga

Infraorder: Elateriformia

Superfamily: Elateroidea

Family: Lampyridae

Subfamilies: Cyphonocerinae

Lampyrinae

Luciolinae

Photurinae

Ototetrinae

Amydetinae

Psilocladinae

As you can see, fireflies are not flies at all (flies belong in the order Diptera), and neither are they bugs (those are of the order Hemiptera). They are actually beetles, as seen by their classification in the order Coleoptera. Anyone who has caught fireflies know that they look nothing like true flies because they have wing sheaths, and true flies never have wing sheaths. True bugs have piercing mouthparts for sucking fluids, and fireflies have well defined mandibles.

The last three subfamilies are not agreed upon by all entomologists, and there is quite a bit of controversy over classification. However, the purpose of this piece is not to quibble over their exact classification but rather to understand some of the behavior and lots of the chemistry behind these fascinating creatures.

They are just getting going here in the Bluegrass. I have found them fascinating since I was little, when my mum would help me catch them and put them in a Mason storage jar with holes in the lid punched by an icepick. She taught me never to hurt them, and after we caught enough to enjoy, we would let them go to catch another day. When I became a scientist (or did being born a scientist just attain another level?), I became intrigued about how they made light. Enough was known about them then to know that their light contains only visible wavelengths, so there is no heat (infrared radiation) associated with it.

We shall get to the chemistry of the bioluminescence of fireflies in a bit, but first let us examine why they have it in the first place. First and foremost, they emit light for mate selection. Many insects that are active at night emit sounds to notify prospective mates of their presence, then once the mate is close enough supplement the sound signals with pheromones to seal the deal. By the way, bioluminescence is a much better term that the sometimes used term phosphorescence because of subtle differences in how different luminescences are produced.

Fireflies are incapable of making sounds, so they substituted production of light instead. Different species have different colors and flash patterns, so species recognition is first by those factors. Once close enough, pheromones take over as in other insects. In most species, both males and females have the ability to produce light, but in a few, only males do. In some species, neither can produce light, having lost the mechanisms for light production in the past. However, taxonomically they are fireflies.

The most common family in the US is the Photurinae. The most common firefly in the eastern and central part of the US is Photinus pyralis, the common eastern firefly, sometimes called the big dipper firefly because of its “dipping” style of flight. The genus name derives from the Greek photeinos, meaning “shining”. The species name is also from the Greek, meaning “of fire”. This is the most common US species, but it is thought that there are upwards of 50 other US Photinus species.

The common eastern firefly is about half an inch long and emits a narrow band (~535 - 620 nanometers) of light with a peak at 562 nanometers. This gives a greenish-yellow light. This species is quite toxic and few predators will disturb it, with one very bizarre exception. Because of this toxicity, children need to learn not to eat them or crush them and then lick their fingers. The high degree of bitterness is a sufficient deterrent, and I have NEVER heard of a child being harmed by a firefly. Do NOT feed them to pets!

The toxicity of this species is due to the presence of a family of cardiotonic steroids called lucibufagins with structures like this:

They are potent toxins and a single firefly has been known to kill a lizard in two cases. Now here is where things get weird. There is another genus of firefly common in the US, Photuris. This genus does not produce lucibufagins, but females of the species Photuris pennsylvanica (Pennsylvania firefly) actually imitate the flash patterns of female Photinus pyralis. When the suitor come to claim his mate, the significantly larger Photuris female kills and eats him, thus acquiring both nutrients and the defensive chemical!

Photuris pennsylvanica is fairly common but has a different color of light. In this species the peak intensity is at 552 nm, with band from ~509 to 640 nm, making its light just a little more yellow, but not really perceptibly different. It is certainly not different enough that the male Photinus notices!

Now for the biochemical magic that fireflies use to produce light. Four materials (in addition to water) are necessary to come together to produce light: luciferin, luciferase, adenosine triphosphate, and magnesium ions. The luciferase is an enzyme that acts as a catalyst and is so not consumed, and the magnesium ions are also catalytic. The luciferin and the oxygen are consumed. The reaction seems to be three stepped:

ATP + Luciferin + Luciferase in the presence of a magnesium ion yields a complex of luceferin, luciferase, and ADP + Pyrophosphate

The next step goes thusly:

The complex just formed + O2 yields AMP + CO2 + Oxyluciferin* (the asterisk indicates that the oxyluciferin is in an electronically excited state.

The last step is Oxyluciferin* falls back to the ground state and emits a visible photon. Since this excited state is a singlet, the emission of the photon happens within nanoseconds.

The AMP is converted back to ATP in the general metabolism since ATP is the general energy currency for almost every living thing. The energy derived from conversion of ATP to AMP and pyrophosphate supplies the driving force for the first step, whilst the energy derived from formation of CO2 drives the second step.

Note that there IS heat produced in this reaction, but it is present in the motions of the molecules rather than in the light that is produced. Therefore, some infrared is produced, but only as an artifact of the oxidation and not in the flash of light emitted. If you could make a huge firefly you would be able to feel its abdomen become slightly warmer after each flash.

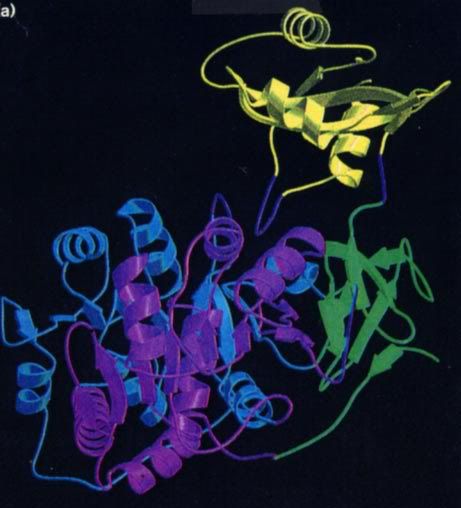

As you see, the luciferase is regenerated in the second step, and that is a good thing because it is an “expensive” molecule for the firefly to make. It is a protein that contains 550 amino acid residues, so it is important that it be conserved. It turns out that there is another enzyme that reduces the oxyluciferin back to luciferin, so it is not wasted, either.

Here are structural formulae for luciferin and oxyluciferin, and a “ribbon” formula for luciferase. Note that these are only correct for firefly material. Other bioluminescent creatures have radically different ones.

It is obvious that fireflies can control when they flash and the flash pattern, so somewhere in the mechanism shown above there has to be a place where the firefly can add or stop adding a key chemical. It has to be either the first or second step, because the third step occurs in femtoseconds. One possibility is that the firefly can control when oxygen is added to the system in the second step. Another is that the firefly can open and close structures that allow one or more of the chemicals in the first step to react. The fact is that this is not yet known. My guess is that the firefly can control when magnesium ions are released in step one since ATP almost always requires magnesium ion to be biologically active.

This IS Pique the Geek! Here is a link to some really cool firefly pictures. I hesitated to paste them here since some of them have a copyright statement. Even though the pictures are beautiful, they are no substitute for seeing fireflies live and in person. Hearing a child squeal in delight when she gets another one for the jar is one of the true joys in life, and I hope to experience that tomorrow evening.

I could go on about how bioluminescence is used in research and in medicine, but I think that this is enough for tonight. Since it is pretty technical in places, I shall give readers time to wrap their heads around this and perhaps I will write a followup sometime in future.

Well, you have done it again! You have wasted many more einsteins of perfectly good photons reading this shining piece. And even though Tommy Thompson realizes that he was lying about Scott Walker on “Huckabee” on the Fox “News” Channel tonight when he reads me say it, I always learn much more than I could possibly hope to teach in writing this series, so keep those comments, questions, corrections, and other feedback coming! Tips and recs are also always welcome.

I shall stick around as long as comments warrant tonight, and shall return tomorrow night around 9:00 PM (unless something wonderful happens) for Review Time. Remember, no science or technology subject is off topic, so you need not limit your remarks to fireflies. I look forward to hearing from you.

Warmest regards,

Doc, aka Dr. David W. Smith

Crossposted at

Daily Kos, and

2 comments

Author

a glimmering piece?

Warmest regards,

Doc

Author

I very much appreciate it.

Warmest regards,

Doc