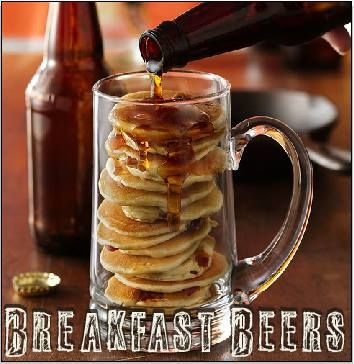

This is your morning Open Thread. Pour your favorite beverage and review the past and comment on the future.

November 15 is the 319th day of the year (320th in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar. There are 46 days remaining until the end of the year.

On this day in 1867, On this day in 1867, the first stock ticker is unveiled in New York City. The advent of the ticker ultimately revolutionized the stock market by making up-to-the-minute prices available to investors around the country. Prior to this development, information from the New York Stock Exchange, which has been around since 1792, traveled by mail or messenger.

The ticker was the brainchild of Edward Calahan, who configured a telegraph machine to print stock quotes on streams of paper tape (the same paper tape later used in ticker-tape parades). The ticker, which caught on quickly with investors, got its name from the sound its type wheel made.

Calahan worked for the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company, which rented its tickers to brokerage houses and regional exchanges for a fee and then transmitted the latest gold and stock prices to all its machines at the same time. In 1869, Thomas Edison, a former telegraph operator, patented an improved, easier-to-use version of Calahan’s ticker. Edison’s ticker was his first lucrative invention and, through the manufacture and sale of stock tickers and other telegraphic devices, he made enough money to open his own lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey, where he developed the light bulb and phonograph, among other transformative inventions.

Stock tickers in various buildings were connected using technology based on the then-recently invented telegraph machines, with the advantage that the output was readable text, instead of the dots and dashes of Morse code. The machines printed a series of ticker symbols (usually shortened forms of a company’s name), followed by brief information about the price of that company’s stock; the thin strip of paper they were printed on was called ticker tape. As with all these terms, the word ticker comes from the distinct tapping (or ticking) noise the machines made while printing. Pulses on the telegraph line made a letter wheel turn step by step until the right letter or symbol was reached and then printed. A typical 32 symbol letter wheel had to turn on average 15 steps until the next letter could be printed resulting in a very slow printing speed of 1 letter per second. In 1883, ticker transmitter keyboards resembled the keyboard of a piano with black keys indicating letters and the white keys indicating numbers and fractions, corresponding to two rotating type wheels in the connected ticker tape printers.

Newer and more efficient tickers became available in the 1930s and 1960s but the physical ticker tape phase was quickly coming to a close being followed by the electronic phase. These newer and better tickers still had an approximate 15 to 20 minute delay. Stock ticker machines became obsolete in the 1960s, replaced by computer networks; none have been manufactured for use for decades. However, working reproductions of at least one model are now being manufactured for museums and collectors. It was not until 1996 that a ticker type electronic device was produced that could operate in true real time.

Simulated ticker displays, named after the original machines, still exist as part of the display of television news channels and on some World Wide Web pages-see news ticker. One of the most famous displays is the simulated ticker located at One Times Square in New York City.

Ticker tapes then and now contain generally the same information. The ticker symbol is a unique set of characters used to identify the company. The shares traded is the volume for the trade being quoted. Price traded refers to the price per share of a particular trade. Change direction is a visual cue showing whether the stock is trading higher or lower than the previous trade, hence the terms downtick and uptick. Change amount refers to the difference in price from the previous day’s closing. These are reflected in the modern style tickers that we see every day. Many today include color to indicate whether a stock is trading higher than the previous day’s (green), lower than previous (red), or has remained unchanged (blue or white).

I must have space on my mind this week, as well as

I must have space on my mind this week, as well as

In times of trouble federally and at the state level, the battle for equal treatment and access moves to the local level.

In times of trouble federally and at the state level, the battle for equal treatment and access moves to the local level.