(10 am. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

This is my very first attempt at anything other than a comment on any site, so please bear that in mind if you choose to read this…

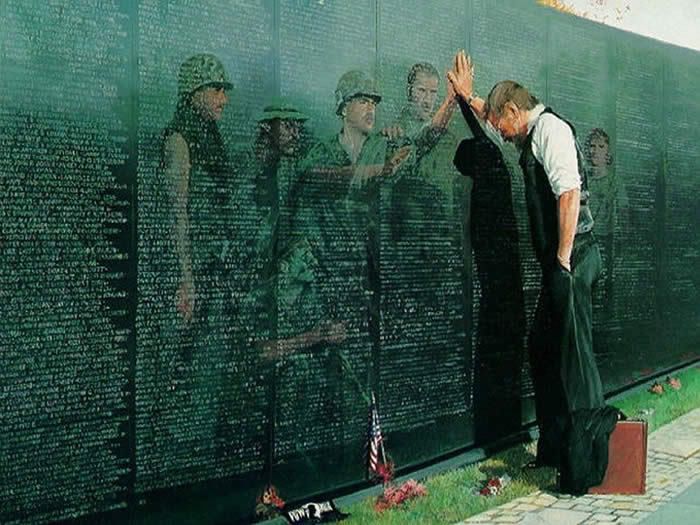

Two names of young men from my Upper Midwest hometown are chiseled into the Vietnam Wall. I was privileged to know both of them.

Our hometown was a modest, unpretentious, somewhat provincial little community. I think of it as Lake Wobegon, only with rivers and hills instead of lakes and prairie. Most were Lutheran. The rest were Catholics, with a few Methodists and Baptists mixed in for the sake of variety. Those of German or Norwegian ancestry predominated. Denizens who could trace their heritage to Central Europe represented the outer limits of cultural diversity in our community. Our town was the county seat, comprised of 1400 long-suffering souls. No one seemed to be rich or poor. There were very few rental properties. Those who did rent did so by choice, not necessity.

Although the state had long been a stronghold for the Democratic Party, the county sent its first Democrat to the State Legislature in more than a century during the 1960s — a former county sheriff who managed to win by just a handful of votes. The area’s heyday had long since passed, having been the most populous county when statehood was granted in 1858. In fact, the county’s population was then less than it had been more than a century earlier.

Steve was a tall, good looking, athletic young man who, perhaps more than anyone else I can remember vividly personified the likeable bad-boy image. Think of a cross between James Dean and Paul LeMat, who played John Milner, the guy with the yellow ’32 Ford Deuce Coupe in the movie American Graffiti. Steve was several years older, but his next younger brother was my classmate. Steve was a marginal student, but managed to remain eligible for football and wrestling. My best friend throughout grade school lived across the street from Steve’s family, so I oftentimes saw him outside, his head buried beneath the hood of his car.

Steve’s “heroics” behind the wheel were legendary. The south hill in town (speed limit: 30 mph) was one of the longest and steepest ascents in the area. Most cars remained in a lower gear. Some said that Steve, from a standing start, accelerated to a speed of 110 mph by the time he reached the top of the hill. Others said that he’d attained 130 mph on level ground.

Once in the Army, Steve volunteered as a helicopter tail gunner, one of the most hazardous jobs available. In June of 1967, with school out for the summer, and our farm still a lush green, I was stunned to learn that Steve had died in Vietnam. His helicopter was apparently shot down and when it struck the ground, all survivors were shot and killed. Steve died only 41 days after his arrival in the country, more than three months shy of his twentieth birthday.

I had been opposed to the United States’ involvement in Vietnam; however, nothing in my life before that time had prepared me for this. We were isolated on the farm, so there was little opportunity to discuss this tragedy with others and even if there had been, few if any who I believed would understand my sentiments.

Steve was gone. It didn’t seem possible. During that summer, I often worked in the barn, alone, listening to the Top 40 music of the time (unless my dad was there, when we were “treated” to polka music). Three songs in particular remain burned into my memory: “Light My Fire” by the Doors; “Up, Up and Away” by the Fifth Dimension; and “If You’re Going to San Francisco” by Scott MacKenzie. Hearing these songs immediately transports me back to that time of trying to make sense of the first loss of someone I actually knew, fearing that there was no sense to be made of all this.

My family purchased an additional farm in the mid 1960s, a 122-acre tract which had been granted to a Civil War Veteran as compensation for his service. The original document bore the signature of Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor. A seven acre field that this veteran had cleared by hand seemed oddly out of place in an area covered with virgin hardwood forest. Most of the remaining timber was cleared so that more acreage could be planted. A large crew, armed with bulldozers, cleared nearly 40 acres of land.

One crew member told me that Steve had worked for them before joining the Army, and although he took risks no one else would dare take, he was a valued worker. On Steve’s last day with them, he said he told Steve that they would miss him and that whenever he returned he had a job waiting for him. Steve replied, “I won’t be coming back.”

I also learned that about three to four weeks prior to his death, his mother had attended the local Memorial Day parade and was said to have remarked, as the Gold Star mothers passed by, that she had a premonition that she would become one of them.

Having moved away immediately after high school graduation, residing on the Left Coast during most of that time, visits to my hometown have typically been rare and brief. I attended a class reunion in 2000, which was held at a local bowling alley. As we were all preparing to leave, I found my former classmate, Steve’s younger brother, who hadn’t joined in on the festivities, sitting at the bar alone, drinking. I thought he appeared to be quite depressed.

The brother struggled in school and had been held back, so he did not graduate with our class. I wondered what Steve’s tragic death had done to him, but was reluctant to risk reopening old wounds. I decided to start a conversation him, which was limited to small talk. His look of loneliness remained with me as I departed.

Kerry was a short, slightly stocky, sad looking young man, who wore thick “Coke bottle” glasses. He had come from one of the few broken homes in our county, having been shuffled from one foster home to another for the past several years. He appeared to be quite muscular, but the appearance was deceiving. My best friend and I were moved to befriend him, partially out of sympathy, but also because we liked him. If we saw him about town, we would pick him up to ride around with us and chatter about anything and everything.

At one point, given Kerry’s rugged appearance, we asked if he had been in many fights. He replied, to our astonishment, that he didn’t dare, because he had a “glass jaw.” He explained that his dad had broken his jaw several years earlier. Tom and I both sat in stunned silence. This was not supposed to happen in our innocent little community.

During the early summer of 1970, Tom and I were riding around with Kerry when he announced that he had decided to join the military service. We both pleaded with him to reconsider, reminding him that he would probably end up in Vietnam. Nothing we could say or do seemed to dissuade him. For several weeks, we no longer saw him around town.

And then he reappeared, complete with his crew cut (which no one wore at the time unless they were in the military service), having completed basic training. He informed us that after this short break, he’d be going to “Nam.” Again, he seemed determined to proceed, no matter what we said to him. We spent as much time with him as we could before he left and upon bidding him farewell, reminded him to stay safe.

I moved away from my hometown in late September, 1970 to begin college, more than two hundred miles away. It marked the beginning of a new life and a dawning realization that the world was much larger than my hometown and surrounding area.

As I was still settling into my new life, my mother called in mid-October to inform me that Kerry had died in Vietnam. Another wave of shock washed over me. An overpowering sense of nausea overcame me. I continued to wonder if anything Tom or I could have said to him might have prevented this tragedy.

Soon after, I learned that Kerry had not died in combat, but had been found dead in his bunk, somewhere in Vietnam. Details were vague and incomplete. We could only speculate. Kerry was eighteen years old, almost four months shy of his nineteenth birthday.

I’m certain that Memorial Day must mean something different for each of us. To me, the memory of these two young men returns almost immediately to my mind. And then I am reminded of a poster that I had placed on the wall of my dorm room, which featured a panoramic shot of the sea of headstones at Arlington National Cemetery, along with the caption that read, “We are the unwilling, led by the unqualified, to do the unnecessary, for the ungrateful.” I recall the two young lives that were so brutally shortened, and again ask myself, “Why?” And then I think of the tens of thousands of other similar stories that played out all across our then-fragmenting nation.

The sense of grief and sadness would be easier to bear if one could be entirely certain that their sacrifices were absolutely necessary. We were constantly warned of the dire consequences that would follow if the United States withdrew from Vietnam. The so-called “Domino Theory” was constantly trotted out, as we were reminded that once the Communists conquered Vietnam, adjacent countries would fall one by one.

The implication was that some day the enemy would eventually land on our shores as part of a large scale invasion. It would only be a matter of time before the ravages of war would be visited upon our own land. Disneyland would resemble Dresden in 1945. Those unconvinced by such reasoning were denounced by the “Silent Majority” as unpatriotic at best, treasonous at worst.

So, I’m again reminded of the question Cindy Sheehan had tried to ask of George W. Bush, which was something like the following: “What was the noble cause for which my son, Casey, died in Iraq?” I don’t believe she ever received an answer.

And then the question arises in my mind: “What was the noble cause for which more than 58,000 young men died in Southeast Asia?” For whatever reason, it doesn’t seem that this question has been asked, at least not in a well-publicized manner. I have yet to find an answer that adequately addresses this question. Perhaps there is none.

So, I remember these two young men, who will remain forever young in my memory, whose lives ended before their adulthood could even begin. I wonder who else might be remembering them on this day. Yet I again feel sadness for the cruel, premature loss of these two people, as well as the millions of others on both sides of wars fought to satisfy the greed and avarice of those for whom war represents an opportunity to seize even more wealth and power, at the same time comfortably immune from any risk of personal loss.

We have much to contemplate on this Memorial Day, each in our own unique way.

Steve and Kerry — may your long sleep be peaceful.

8 comments

Skip to comment form

own reminisces of the friends who went to “Nam”, and those who didn’t. I lost my very best friend to that war, and years later, sobbed like a baby when I ran my hand over his name on “The Wall”…..

Someone once said, “War is hell for those who go, and also for those who stay behind.” I’m not sure that’s the exact quote, but the sentiment is exact, ….and quite true.

fellow members can compliment your work with “ponies”, or, if they didn’t like it, one of the other choices. I’ll give you a “pony”!

Author

I might also add that I had the honor of seeing Steve and Kerry’s names on the Vietnam Memorial, first on the Moving Wall when it made a brief stop in my community, and then twice in Washington, D.C.

During my first ever visit to Washington, D.C., on the day after the November 7, 2000 election, I was able to see the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and was able to find their names, both of which located were near the center, out of reach for anyone less than 7 feet tall. It was a beautiful day, weather-wise, and a few remnants of fall color could still be seen. Finding their names was a very emotional experience, and then looking at the many columns of names both to my left and right made the experience almost overwhelming. Numbers alone pale in terms of impact compared with such graphic visual imagery.

And then there was the matter the night before of the Presidential Election that had been called for Al Gore, and within a short time, the network revised their prediction, stating that the election was too close to call. The city was unusually quiet that day, and seemed otherworldly, something I could only describe as an ominous sense of foreboding.

During the second visit, in late March of 2008, the cherry blossoms were in full bloom, and despite the beauty of the surroundings, the impact of “The Wall” was even greater than it was the first time. A helpful volunteer with a stepladder made rubbings on paper for both Steve and Kerry, which are now among my most valued keepsakes.

Please accept my thanks to those of you who have taken the time to read this, and I do hope that your Memorial Day weekend was both pleasant and meaningful.

It’s always great to learn about the real people behind the statistics/news . . .

and I hope to see more of your writing. I stand with you, in heart, at the Wall, where my brothers name is also written.

Those who sacrifice the lives of others in unnecessary wars cannot answer Cindy, or any of us, because there is no noble cause. None. At. All.