(9 am. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

40 years ago the first UnThanksgiving Day happened.

Oh, it wasn’t called that then. Nor was it called that the following year. You see, it wasn’t about Thanksgiving at all. It was about the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, and federal policy for native Americans.

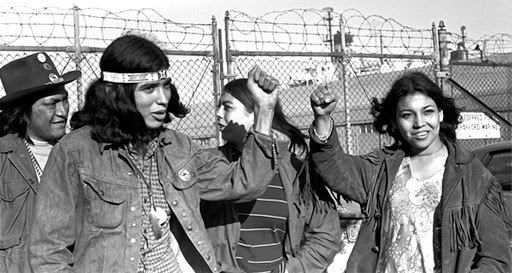

On November 20, 1969, 79 native Americans adults and six children symbolically claimed Alcatraz Island for United Indians of All Tribes, and so started the American Indian Movement (AIM).

This wasn’t the first time indians had tried to take the island. In 1963 the federal government closed Alcatraz prison and declared the island “surplus federal property”. Under the Fort Laramie Treaty, surplus property was supposed to be returned to native Americans. Richard McKenzie and five other Sioux Indians realized the significance of this action.

On March 9, 1964, McKenzie, Allen Cottier, Martin Martinez, Garfield Spotted Elk, and Walter Means, symbolically occupied Alcatraz Island for four hours. They wanted to use the island for a native American studies center and museum, but were ushered off the island by federal marshals after a few hours. Three weeks later the same group filed a claim in court. The U.S. Attorney’s office ignored the claim and transferred custody of the island to the General Services Administration (GSA).

Meanwhile, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors was pitching the idea of Alcatraz Island being used as a park and recreational site. By 1968 the courts had dismissed all of McKenzie’s complaints, and in October of 1969 the GSA got behind the idea of Alcatraz being a federal park. Bay Area indians decided to take action.

The Chief of Alcatraz

Richard Oakes was described as a handsome, charismatic, talented and natural leader. Already an indian activist, he was the one most responsible for Alcatraz being occupied. On November 9, 1969, Oakes, Jim Vaughn (Cherokee), Joe Bill (Eskimo), Ross Harden (Winnebago) and Jerry Hatch, convinced the owner of the sailing ship Monte Cristo to take them to circle the island. Before leaving Pier 39 they read a proclamation offering to buy the island for $24 and some beads. While doing so, the group jumped overboard and swam to the island. They claimed it by right of discovery. The following day the Coast Guard and GSA asked them to leave, and they did. No arrests were made. Oakes made certain that the press was involved at every step of the way.

It was during this time that Oakes realized that a more permanent occupation of the island was possible. Up until this point it was mostly Bay Area indians that were involved. Oakes went down to UCLA to recruit a larger group.

The average annual yearly income of a native American in 1969 was about $1,500 – one quarter of the national average. Their life expectancy was 44 years, as opposed to the average American of 65 years.

Even more importantly, the culture of the first Americans had been crushed. American Indian studies programs at universities were few and far between.

The U.S. government policy of Relocation and Termination encouraged indians to leave their reservations, and 200,000 took up the offer. But for most it was merely a one-way ticket to unemployment in a big city. In October 1969, the San Francisco Indian Center, a place of refuge for homeless indians, burnt down. Native Americans once again looked at the abandoned island of Alcatraz.

“We hold The Rock”

On the morning of November 20, 1969, 79 Native Americans landed on Alcatraz. The Coast Guard belatedly attempted to block the landing, but failed.

Glenn Dodson, the island’s caretaker, advised them that they were trespassing. He then directed them to the old warden’s residence, where they set up their headquarters and celebrated.

The Coast Guard set up a blockade of the island to prevent supplies getting in. That afternoon lawyers from the Department of the Interior arrived on the island and gave them 24 hours to leave. The group didn’t budge.

“We invite the United States to acknowledge the justice of our claim. The choice now lies with the leaders of the American government – to use violence upon us as before to remove us from our Great Spirit’s land, or to institute a real change in its dealing with the American Indian. We do not fear your threat to charge us with crimes on our land. We and all other oppressed peoples would welcome spectacle of proof before the world of your title by genocide. Nevertheless, we seek peace.”

– Richard Oakes’s message to the Department of the Interior

The new occupiers of the island made very simple demands. They wanted the land that the government deemed surplus to be returned to the Native Americans according to the Treaty of Fort Laramie. They also wanted enough funds to build and maintain an indian cultural complex and university. The government pretended to negotiate, but they rejected all demands.

A governing council was elected and everyone was given a job. Security, sanitation, day-care, cooking, laundry, etc. In the communal environment, all decisions were voted on by everyone. Within three weeks a school was set up.

The occupation quickly gained major media attention, and a certain amount of public sympathy. It was also a rallying point for Native American activists. One of those activists was John Trudell.

By 1972 John Trudell was chairman of AIM, and would later become a successful musician, author, and movie actor. But in 1969 he was just another Vietnam veteran and college drop-out. When Trudell heard about the occupation he packed a sleeping bag and headed for Alcatraz. Once there he became the voice of Radio Free Alcatraz, a pirate radio that was rebroadcast with the help of other stations.

The response was overwhelming.

Donated food and money poured in from everywhere. The Grateful Dead and Creedence Clearwater Revival played a concert on a boat anchored just off of Alcatraz, and then donated the boat to the cause.

Trudell and his wife Lou had the only baby born on Alcatraz, named Wovoka. By Christmas 1969 there were 200 living on the island.

Space was rented at Pier 40 by members of the longshoreman’s union, where supplies were collected and ferried to the island.

During the occupation around 5,200 people came to Alcatraz to participate. Some just for the day. Some for months.

Indians of All Tribes

The downfall of the occupation started on January 3, 1970, when Oakes’ 13-year old daughter, Yvonne, fell over a railing from the third-floor of their apartment building to her death.

Following her death, Oakes left the island, and with him the group was left without a clear leader.

Many of the original occupiers were students, and they left to go back to school. The new tenants were less idealistic and many of them had drug problems. Some non-indians from the hippie culture moved into the island.

Factions developed and two major groups fought for their own version of an indian utopia. The people who lived there described it as anarchy.

When negotiations with the government in April and May of 1970 failed to gain any traction, the government cut off all power and telephone service to the island, and also removed the water barge.

Just a few days later, a fire broke out on the island that destroyed the warden’s quarters, doctor’s quarters, and the inside of the lighthouse.

The federal government took a hands off approach, hoping to wait out the occupation rather than make martyrs.

Without electricity to the lighthouse there was no light or fog horn. Government workers went to the island to repair it, but were met by armed indians who demanded that they restore the water first.

Soon public opinion turned against the occupiers, and the press began publishing stories about beatings and assaults on the island.

Supplies began to run low. Residents began stripping the copper tubing of the buildings to sell to pay for food and supplies. Three were arrested and convicted. The living situation on the island began to get grim.

In mid-January two tankers collided and spilled 800,000 gallons of oil into the bay. Although Alcatraz was ruled to not be an issue, some blamed the lack of a lighthouse anyway.

On the negotiation front, the indians turned down an offer of part of nearby Fort Mason in exchange for giving up the occupation. The Nixon Administration began forming a plan to take back the island.

On July 11, 1971, a large force of federal marshals and FBI agents landed on the island to end the occupation. They found only six men, four women, and five children.

Afterwards

The occupation is universally considered to be a success, not because it achieved its goals, but because it started a vocal and militant indian rights movement.

President Nixon announced a new policy of “self-determination without termination” for Native Americans on July 8, 1970.

Robert Oakes died on September 20, 1972, when he tried to intervene in a dispute between a group of indian youths. A local security guard shot him when he suspected Oakes was reaching for a gun.

1 comments

Author

Happy UnThanksgiving to you.