Part One of a collaborative two-diary, cross-curricular series – look for pico‘s diary on Gilgamesh in Tuesday’s Literature for Kossacks.

One of the moonbatisms that least endears me to the faculty of my school’s Language Arts department is my relatively frequent assertion that all English teachers are, in fact, wannabe Social Studies teachers. It’s really only a joke – in truth, I recognize that the one can hardly exist without the other. Without history, literature has no context; without storytelling, history becomes a dry pile of dates, names, and un-understood, colorless societies.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight your resident historiorantologist will attempt to avoid the latter fate in setting the stage for pico‘s upcoming piece on that Sumerian par excellance, Gilgamesh the Wrestler. Our tale begins, appropriately enough, at the very dawn of civilization itself…

The Grey Before the Dawn

Ah, to have lived in the care-free days of the Neolithic Era! With only a few hundred thousand humans scattered about the planet, nomadic tribes looking to go agrarian after the Ice Age leftovers had run out pretty much had their pick of river valleys in which to trade tents for towns. In Egypt, such folks deployed along the Nile; in China, on the banks of the Huang He; and in India, near the mighty Indus. In ancient Iraq, migrants (likely from the highlands of Iran and western Turkey) made their way down the verdant Tigris and Euphrates Valleys, finally settling between the two in what the Greeks would later term (with typically Greek geography-mindedness) “Mesopotamia,” or the “land between two rivers.” You’ll remember that “two rivers” theme from this Golden Oldie of the Iraq Debacle:

As these first farmers pushed southward – this would be around 6000-3000 BCE (or, according to this crank, well before the Creation of the universe) – they found a land verdant with game and soil rich with silt deposits from thousands of years of regular flooding. These silt deposits have, over the course of millennia, pushed the northern shores of the Persian Gulf far south of where they used to be: put in today’s terms, Basra would be deep under water, and the beach at Abu Shah Rain would be only a short-but-incredibly-harrowing 3-hour drive from Baghdad.

The early inhabitants of the land between the rivers found the land amazingly fertile (though likely no one put together the crescent shape of the whole thing until the age of empire-builders kicked off a couple of thousand years later). In the mud they planted wheat, barley, chickpeas, lentils, dates, mustard, and onions, and in time learned to domesticate oxen, sheep, goats, pigs, donkeys, and perhaps even onagers, the Asian Wild Asses that bucked so hard that the Romans named a catapult after them. It seems they may have actually brought some of the earliest ideas regarding irrigation canals and temple-centered worship with them; prehistoric pottery evidence links the Ubaid Period in southern Mesopotamia (5300-3900 BCE) with the Samara culture in the north, which itself was among the earliest of irrigation agriculturalists.

(Wikipedia Commons image of a larger map showing much of the ancient coastline of the northern Persian Gulf here)

As these waves of migrations turned into settlements along the southern banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, a new culture developed, distinct from those of the already-extant societies in the area, though built upon their religions and customs. They were called the Sumerians by the Semitic Akkadians (the next up in the centuries-long parade of civilizations that have tried to exert their will over the people of Mesopotamia), in reference to the common language of the inhabitants – they apparently referred to themselves as “the black-haired people.” They were celebrating diversity long before it was fashionable to do so, blending the ideas of arriving tribes and bands with a native talent for innovation to create a constellation of linguistically-linked city-states whose advancements continue to define some of the most basic aspects of our own society.

Inventing Civilization

In this era before the development of writing – and thus, before history itself – the bulk of human cooperative effort and problem-solving skills were devoted to flood mitigation and the construction of irrigation works. This was a fact of life in most river valley civilizations: the rivers that nourished their crops were fickle things, just as likely to inundate hundreds of square miles beneath flood waters as they were to simply deposit an annual tribute of fertile silt and then peaceably recede. Lacking knowledge of how climate works (and no doubt afflicted by the same kind of naysaying boobs with whom we contend today), they anthropomorphized their surrounding into a pantheon of gods, then began pondering means of how to keep those deities pleased. Cleary, something needed to be done, and the answer – in addition to an increasingly-complex religious structure – was a mind-boggling system of canals, ditches, and irrigated croplands.

In this era before the development of writing – and thus, before history itself – the bulk of human cooperative effort and problem-solving skills were devoted to flood mitigation and the construction of irrigation works. This was a fact of life in most river valley civilizations: the rivers that nourished their crops were fickle things, just as likely to inundate hundreds of square miles beneath flood waters as they were to simply deposit an annual tribute of fertile silt and then peaceably recede. Lacking knowledge of how climate works (and no doubt afflicted by the same kind of naysaying boobs with whom we contend today), they anthropomorphized their surrounding into a pantheon of gods, then began pondering means of how to keep those deities pleased. Cleary, something needed to be done, and the answer – in addition to an increasingly-complex religious structure – was a mind-boggling system of canals, ditches, and irrigated croplands.

By that point in our history, about the most complicated undertaking we humans had attempted were large, coordinated hunting trips, so it fell to those first river valley pastoralists to figure out a way of organizing the labor needed to build and maintain the waterworks – and the concept of government was born. Oddly, the first (circa 3000 BCE) non-family-unit-based hierarchies bore a lot of similarities with modern neocon “thought” on the structure of government, relying on priests who interpreted the will of the gods through the CNN-esque method of examining the entrails of sacrificed animals, then making pronouncements as though they were the only god-interpreters in the room. Around these priests grew centers of pilgrimage whose roots stretch back past recorded time; Eridu, one of the earliest, may have been marrying government and religion as early as 5000 BCE.

Irrigation works begat food surpluses, and those surpluses in turn begat a system of labor specialization still in use today. Reliable watering methods meant that it took fewer farmers to produce more food, which in turn permitted societies to relieve some of their members of planting-and-harvesting duties in favor of other pursuits. The priests (and the later priest-king-led bureaucratic governments) were just the first example of such specialization, and in fairness, it must be said that they were pretty productive with all that non-farming down time. It was, after all, their need to confidently predict the ebbs and floods – and to know when best to plant, harvest, or raid the next town’s fields – that resulted in Sumerian priests spending long centuries gazing at the stars in the night sky, noting the long- and the short-term rhythms that accompany the harmony of the spheres.

The Priests of Ancient Mesopotamia: Unsung Original Tormenters of Schoolkids Everywhere

Of course, even an entire lifetime spent stargazing isn’t worth much if you can’t pass along what you’ve learned, and over time, the Sumerians developed several methods of paying the knowledge forward. Out of the sky watching grew a mathematical system based on multiples of 10 and 6, with 60 being a number associated with An, the god of the sky and the highest-ranking deity in the pantheon. 60 has the added convenience of being divisible in a whole host of ways, and the Sumerians used it to create a system of uniform weights and measures around which they could build both a legal system and an economy. One mina (about a pound) of silver equated with 60 sheckels, for example, and it was the Sumerians who first started selling things by the dozen – 12 being one-fifth of 60, after all.

It might be considered remarkable that we in the 21st century CE buy our eggs in quantities determined by ancient Iraqis, but the hold of these people upon our time-obsessed modern society goes even deeper: It was the Sumerians who first divided the circle into 360 (60×6) degrees, and in doing so, they defined the shape of watches and clocks thousands of years into their future. To this day, bodies as self-indulgent as the U.S. Congress spend hours (each of 60 non-coincidental minutes, btw) monkeying with essentially Sumerian methods of timekeeping – pdf. The Sumerian understanding of the stars has influenced recent American policy in other ways, too, if one considers that they laid the basis for what would become the Babylonian science of astrology – check out this tidbit, which seems to indicate that Ronald Reagan’s appreciation of the zodiac predates the Joan-Dixon-White-House years:

Reagan became noted as being one of the few governors to actually sign astrology legislation when on August 30, 1974, as Governor of California, he signed legislation which became Chapter 583, and added Section 50027 to the government Code, relating to astrology. The legislation removed Sacramento licensed astrologers from the category of fortune tellers, thus allowing them to practice their trade for compensation.

The Sumerian legal code was administered by priests and was highly respective of property rights, which makes sense if viewed from the perspective of all property ultimately belonging to the gods. Each of the growing cities had a temple dedicated to its local deity, and a staff of priests to attend him and interpret his will – a convenient, all-in-one legal/religious/social hierarchy of the type these psychos would just love to impose upon the land of the free.

Awright, class: get out a lump of clay and a wedge-tipped reed…

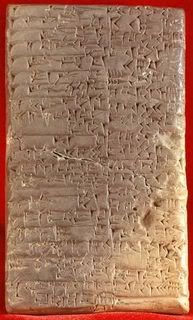

History begins with dawn of writing, so your resident historiorantologist has a special place in his heart for the first group of folks to ever figure out a way of preserving thoughts. Though they started by barking up the same hieroglyphic tree as the Egyptians, the Sumerians found that pictures were easier to draw when they were stylized (!) a bit. In the case of their cuneiform writing system, a wedge-shaped piece of reed was pressed into a wet piece of clay to make various configurations of impressions. The pictures thus created were intelligible across linguistic barriers, as they did not rely on an Egyptian-style understanding of the phonics behind the hieroglyphs – as long as they both knew what the images represented in their own languages, a Semitic trader could do business with a visiting Aryan merchant solely by making divots on a small slab of clay.

History begins with dawn of writing, so your resident historiorantologist has a special place in his heart for the first group of folks to ever figure out a way of preserving thoughts. Though they started by barking up the same hieroglyphic tree as the Egyptians, the Sumerians found that pictures were easier to draw when they were stylized (!) a bit. In the case of their cuneiform writing system, a wedge-shaped piece of reed was pressed into a wet piece of clay to make various configurations of impressions. The pictures thus created were intelligible across linguistic barriers, as they did not rely on an Egyptian-style understanding of the phonics behind the hieroglyphs – as long as they both knew what the images represented in their own languages, a Semitic trader could do business with a visiting Aryan merchant solely by making divots on a small slab of clay.

In honor of LNK, who frequently drops by the Cave with lovely gifts of context and flavor, I present this for the uber-interested: an enormous pdf of a Sumerian lexicon. Enjoy!

Despite developing writing itself, literacy was not high among the ancient Sumerians – in fact, in the scenario above, it’s more likely that the Semite and Aryan would have hired one of the scribes that hung around the marketplaces to do their writing, translating, and notary-publicking for them. Much of what survives of Sumerian cuneiform tablets are the work of such scribes, or are the practice work of students assigned to copy texts, but from them we get a glimpse of the complex, exacting, and very modern-sounding tenor of the ancient Mesopotamian legal code:

Contract for the Sale of a Slave, Reign of Rim-Sin, c. 2300 B.C.

Sini-Ishtar has bought a slave, Ea-tappi by name, from Ilu-elatti, and Akhia, his son, and has paid ten shekels of Silver, the price agreed. Ilu-elatti, and Akhia, his son, will not set up a future claim on the slave. In the presence of Ilu-iqisha, son of Likua; in the presence of Ilu-iqisha, son of Immeru; in the presence of Likulubishtum, son of Appa, the scribe, who sealed it with the seal of the witnesses. The tenth of Kisilimu, the year when Rim-Sin, the king, overcame the hostile enemies.

Contract for the Sale of Real Estate, Sumer, c. 2000 B.C.

Sini-Ishtar, the son of Ilu-eribu, and Apil-Ili, his brother, have bought one third Shar of land with a house constructed, next the house of Sini-Ishtar, and next the house of Minani; one third Shar of arable land next the house of Sini-Ishtar, which fronts on the street; the property of Minani, the son of Migrat-Sin, from Minani, the son of Migrat-Sin. They have paid four and a half shekels of silver, the price agreed. Never shall further claim be made, on account of the house of Minani. By their king they swore. (The names of fourteen witnesses and a scribe then follow.) Month Tebet, year of the great wall of Karra-Shamash.

Alphabetic systems were even easier to use, and gradually Aramaic written in a Phoenician script supplanted cuneiform as the predominant means of written communication in the Middle East. Cuneiform survived in the 1st century CE, but by then was known only to a handful of scholars and priests. Its wide acceptance in its day, however, is what saved it from obscurity in the end: in 1835, a British East India Company officer traveling through Persia was shown the The Behistun Inscription, and Darius the Great’s 3-language billboard of his own triumphs turned out to be cuneiform’s Rosetta Stone.

Who Wants to Play King of the Ziggurat?

pico will be behind the podium on Tuesday, addressing in detail some of Sumeria’s significant contributions to literature, so I’ll resist the temptation to talk about the semi-mythic priest-king of Uruk and his quest for immortality. It might be good preparation, however, to take a look at the kind of place Uruk was, since the city lends its name to an entire period in the story of Sumeria (4500-3100 BCE).

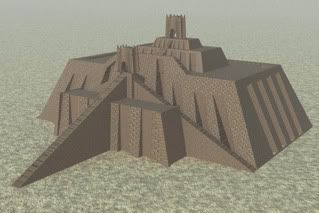

The first cities to attain prominence in lower Mesopotamia were Nippur in the north and Eridu in the south, but by 4500 BCE or so, their power was waning with the rise of Uruk. Like all the major Mesopotamian city-states, at its heart lay a ziggurat, a step-sided pyramid topped by a temple to the city’s patron god. Constructed of mud bricks (either sun-dried or kiln-baked; quite an advancement in their own right), ziggurats were meant to resemble mountains, upon whose un-floodable heights the Sumerian gods were thought to dwell, and some of them were every bit as imposing as a real peak:

The Ziggurat of Ur …today

Choqa Zanbil, near Susa, Iran British spy HQ

Clustered around the ziggurat were houses and shops constructed of mud-brick and, as one got further from the city center, reeds. By the Uruk Period, trade items were coming in from far-flung locales – archaeological evidence suggests that Mesopotamia was at the heart of ancient world trade routes that stretched from the Indus to the Nile. The colonies established by Uruk, such as the one at Tell Brak in modern Syria, did their part in diffusing their mother culture amongst the developing civilizations that would someday supplant them, and help to explain why Babylonian law codes and Akkadian messiah stories have so much in common with certain writings in the Bible.

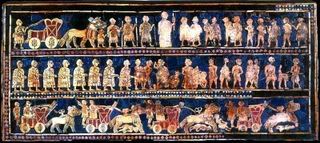

Toward the end of the Uruk Period, the Sumerians really opened Pandora’s Box when they started smelting tin and copper together to create bronze, the military applications of which were easy to behold. Same story with the chariot, which was invented around the same time as the bronze blade, but was generally used for transport around the battlefield as opposed to frontal assault. Weapons improved over the long history of Sumer, but in general, soldiers were equipped with bronze-tipped spears, copper helmets, and leather shields. Some city-states probably had small armies of professional soldiers, but conscripted farmers were often used in larger conflicts. Armed with implements from their farms, these men were sometimes plied with courage-giving beer before battle; the result was probably more akin to a gigantic, deadly rugby scrum (and one that often destroyed the very irrigation works and fields over which they were fighting) than it was to the ordered rank-and-file of, say, the Romans who would arrive in a couple of thousand years.

Toward the end of the Uruk Period, the Sumerians really opened Pandora’s Box when they started smelting tin and copper together to create bronze, the military applications of which were easy to behold. Same story with the chariot, which was invented around the same time as the bronze blade, but was generally used for transport around the battlefield as opposed to frontal assault. Weapons improved over the long history of Sumer, but in general, soldiers were equipped with bronze-tipped spears, copper helmets, and leather shields. Some city-states probably had small armies of professional soldiers, but conscripted farmers were often used in larger conflicts. Armed with implements from their farms, these men were sometimes plied with courage-giving beer before battle; the result was probably more akin to a gigantic, deadly rugby scrum (and one that often destroyed the very irrigation works and fields over which they were fighting) than it was to the ordered rank-and-file of, say, the Romans who would arrive in a couple of thousand years.

Be There at the Start of a Long, Sad History

The Sumerian king list tells us that Uruk was slipping from its leadership position as the three-thousand year countdown to the birth of Christ was about to get started. By then, other cities such as Kish, Lagash, Agade, Akshak, Larsa, and Ur (birthplace of the prophet Abraham) were waxing under the leadership of a kingly class that was distinguished from the earlier priestly leaders by their secular nature and slightly more above-board application of the legal code. As I mentioned before, the flavor of Sumerian law can certainly be tasted in the Babylonian Code that Hammurabi issued around 1750 BCE:

If an overseer or a fisherman ordered to the service of the king does not come, but sends a hireling in his stead, that same overseer or fisherman shall be put to death, and his house shall go into the possession of the hireling.

When a shepherd of small cattle, after having driven the herd from pasture, and when the whole troop has passed within the city gates, drives his cattle to another man’s field (within the city walls), and pastures it there, that shepherd shall take care of the field, which he has given to his flock as pasture, and shall give to the owner of the field for every day the amount of sixty qa.

Though they certainly were fighting long before anyone in any of the city-states thought of inventing a way to write it down, an interesting/chilling thing to note is that Iraq is possibly home to earliest recorded war in history – a conflict between Lagash and Umma in 2525 BCE. The fighting would continue intermittently for centuries, virtually ensuring that some “the Great” or other would stride out of the obscurity and unify everyone into an empire. Eventually one did, but before we get to his story, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the profound impact all the fighting had on the societies and cultures of the region. Here’s a lament from an Iraqi who lived 4000 years before anyone strung together the words “post-traumatic stress disorder:”

“WHAT STRANGE CONDITIONS EVERY WHERE!”

My god has forsaken me and disappeared,

My goddess has failed me and keeps at a distance.

The benevolent angel who walked beside me has departed,

My protecting spirit has taken to flight, and is seeking someone else.

My strength is gone; my appearance has become gloomy;

My dignity has flown away, my protection made off….

The king, the flesh of the gods, the sun of his peoples,

His heart is enraged with me, and cannot be appeased.

The courtiers plot hostile action against me,

They assemble themselves and give utterance to impious words…. They combine against me in slander and lies.

Historiorant:

Gilgamesh is thought to have lived in Uruk sometime during the early dynastic period; the Conqueror-Guy referred to above is Sargon of Akkad, whose story I’ll fresh out of time to tell tonight. That’s okay, though; we’ve gotten to the Sumer that Gilgamesh knew, so it must be time to yield the podium to my colleague from Literature for Kossacks, and ask readers to tune in on Tuesday night for a good, thorough look at some oddly familiar literature.

Gilgamesh is thought to have lived in Uruk sometime during the early dynastic period; the Conqueror-Guy referred to above is Sargon of Akkad, whose story I’ll fresh out of time to tell tonight. That’s okay, though; we’ve gotten to the Sumer that Gilgamesh knew, so it must be time to yield the podium to my colleague from Literature for Kossacks, and ask readers to tune in on Tuesday night for a good, thorough look at some oddly familiar literature.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, and DocuDharma.

9 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

how little time I’ve been able to set aside for Civilization lately. Talk about a love/hate relationship – you get to conquer the world, but that’s 20 hours you’re never gonna get back.

It’s too, too early now to really understand this, however I will come back later today and enjoy it at leisure! I did want to take this opportunity to thank you for doing this series and especially for cross-posting here (I don’t do orange much anymore) I’ve learned so much through your efforts and I wanted you to know (^.^)

will be back after work to savor and really read this. Your histories have always been one of my favorite things about blogging. I loved the one you did awhile back on Babylon, and the first one I read, Afghanistan. My husband is a history buff of ancient civilizations and for months he had the Epic of Gilgamesh in the bathroom as reading material. Every once in a while I would browse through it and read. It scared the crap out of me. Really was a big mess o hacking and hewing, and it’s so ancient that it has a strange quality of while being part of human literature, of being almost science fiction or alien. I look forward to Pico’s essay on this primal piece of literature.

“…did their part in diffusing their mother culture amongst the developing civilizations that would someday supplant them,…” This is an understatement of epic proportions! I am very grateful for your writings which elevate the discourse on the Tubes immeasurably. Gotta say that “mother culture” is really not getting it though. The Goddess orientation of the Sumerians and its diaspora is the underpinning of much of the ongoing clash of religions that is evident today. When one reads the Old Testament as the documentary of the genocidal domination of these people, to fail to mention Inanna as the center of the culture is …well, short shrift. I hope you will consider expanding this conversation in future episodes. Love this site!