|

Time is a sort of river of passing events, and strong is its current; no sooner is a thing brought to sight than it is swept by and another takes its place, and this too will be swept away. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations. iv. 43 |

There are some things that will always be constant. Things infinite in the sense that it is beyond imagining a time ahead in which such things do not occur or exist. The tide is one of these things.

I know of a river where the water looks like thickened latte on most days. The confluence of salt water tide into fresh water river creates an almost viscous liquid and I wonder, when I dream of this river, if the water still feels like cold distilled syrup.

|

“An estuary is a semi-enclosed coastal body of water which has a free connection with the open sea and within which sea water is measurably diluted with fresh water from land drainage.”

PRITCHARD, D. W. 1967. “What is an estuary?” |

The technical term for the Coquille River is “Drowned River Mouth Estuary”.

A drowned river mouth estuary is a bountiful place, full of biological oddities of nature, some prehistoric, some not. Several creatures and plants survive very well in the nutrient and oxygen-rich environment of a river or bay where salt and fresh water meet. On the larger side, think of seals and fish, of birds and amphibians. Marsh plants do well; though they are delicate ecologically, they are so adapted to the changing content of the water and the different mineral stew of the river sediment, that changes seasonally with the tides do not affect their survival unless there is drought. Such plants do well as long as man doesn’t attempt to reclaim too much of the shoreline or discard too much garbage in the mouth of the marsh. To our undiscerning human eyes, marshy, swampy areas often look aesthetically like so much waste land, layered with decayed and rotting flora, and dry grasses and reeds that rise out of the changing levels of the water.

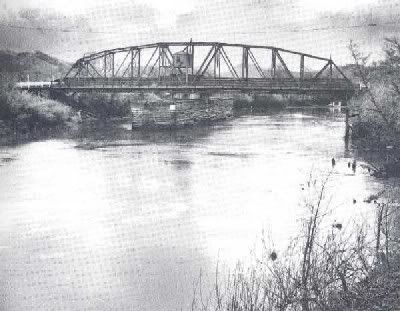

Over the course of European man’s encroachment on the Pacific coast, such swamps have historically been used as our private recycling centers. A marsh wasteland is a rich place, though, and there are dozens of wealthy, though endangered ones on the Oregon south coast. In 2005, Congressman Peter De Fazio was instrumental in securing funds to protect marshlands, and in particular, the Bandon Marshlands adjacent to the Coquille River Bridge, by making certain that road improvements scheduled for the area included a critical restoration and rehabilitation project for the marshes surrounding the Coquille River, the bridge and the stretch of Highway 100 through the marshlands.

The tidal wetlands restoration project, made possible by the road improvements, will be the largest estuary wetlands restoration ever undertaken in Oregon, opening up more than 400 acres of diked former tidelands on the refuge to provide essential habitat for juvenile salmonids, including federally listed coho salmon. Migratory birds, particularly waterfowl and shorebirds, will greatly benefit from the restoration. The restoration project will also help protect against degradation numerous cultural resources sites of importance to the Coquille Indian Tribe, including remnants of a historic Indian fishing camp that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and considered to be one of the most important cultural resources sites in Oregon.

The Nature Conservancy Applauds Congressional Support for Oregon’s Bandon Marsh Wildlife Refuge

|

To maintain a navigable river means housekeeping the waterways of deadheads (submerged cut logs too long in the river and saturated enough to lurk below the river surface) and wind damage that floats down the river from farms and forests upstream. |

There is irony in the term “Drowned River Mouth Estuary”, if only for me. My father drowned on this river, near those critical marshland by the Coquille River bridge in 1969, after spending almost two decades moving up and down this water route, from salt water to fresh and back again. Many days he and I crossed the river bar to the ocean, as we towed log rafts out to sea. The inevitableness of dragging debris to sea, only to have the tide return it to shore, hangs around my mind sometimes. I never questioned it out loud as a kid, but I often wondered why we towed those logs to sea, when I thought they would in fact return on the next incoming tidal current. I guess my dad knew the flow of the eddies and currents, and that the direction of the wind would likely drive the abandoned debris to more southern reaches of the shore away from the river mouth. I assume this to be the case, though I will never know. There was always so much debris to clear after every flooded early Fall and through a long drenched winter.

That syrup of the Coquille is the mix of things fresh and salty, muddy and dense, liquid and solid sediment. Fresh water is less dense than salt water and when the two meet, wherever they meet because you never really know from one tide to the next where the margin will be between river outflow and tidal incursion, fresh water slides over salt water. On rainy days, that fresh water is filled with debris and mud from erosion upstream and the river flow comes down with force against the incoming salt tide. The resultant sedimentary debris that floats to the bottom of the river changes the under tide pattern of the salt water layer and the bottom of the river is a mercurial and ever changing map, the topology of which is never stable in depth or breadth.

Along the bottom, the current moves mud and sludge that piles up in drifts with every tidal exchange between fresh and salt water. The Army Corps of Engineers has for many decades come to the Coquille to dredge the bottom. If this visit doesn’t occur on a reasonably regular basis, the Coquille would grow shallow, too shallow for the draught of lumber barges or deep draught ships, though there are fewer of these now. The river bar of the Coquille is still the most dangerous on the Oregon coast, second only to the Columbia River bar. The area between the north and south jetties is narrow and the incoming Pacific Ocean tide is so fierce that the cresting bar waves are never predictable. Factor in a wind that is almost constant and you have the mariner’s perfect fatal nightmare. Cape Blanco just to the south of Bandon has been clocked as one of the windiest places on earth (as mentioned in an earlier essay, The Big Blow).

My father worked on the Port of Bandon tugboat as first engineer in the 1950’s; the captain of the boat was one of my dad’s old Alaska buddies from the late 1930’s, so the job was a good fit for my father.

|

The Port of Bandon tug operated out of the marina in Bandon near the mouth of the Coquille. This port was a less than majestic port, but truly functional as a midcoast center and terminal for lumber shipping operations and a healthy fishing industry. Those days are gone; the old Moore Mill machine shop and the city dock, I believe, are both removed or renovated to suit more tourist-oriented attractions. “Touristification” has been the fate of most coastal Pacific towns as timber and fishing fail. I often wonder how many people are still familiar with the term “gyppo logger” and if there are any left. I remember nights at 9 pm in the summer when my dad would take me to the city dock to watch the trawlers return with their catch. Huge halibut, ugly creatures, and red snapper, so prehistoric seeming, and tons of salmon the size of which seem to dwarf the fish tossed around at Seattle’s Pike Place Market now. I was a child and all things were bigger then.

The Oliver Olson barge ran aground on the south jetty of the Coquille River in 1953 and from what I remember of the story, it was because the barge operator refused to wait for the Port of Bandon tug to pilot it to sea from the mill upriver. Andy, the captain of the Port of Bandon insisted wisely on the window of tide that granted a safer passage of a fully loaded barge across the bar. The Oliver Olson started out, but as she attempted the bar crossing, the currents pushed her south and hard against the outcropping of piled basalt rocks of the Coquille’s south jetty. Dumped timber was everywhere – out to sea, upriver, washed up on the beaches.

Most of the timber was salvaged; the barge was a loss. They stripped her down and sliced her steel hull horizontally at around midpoint about 6 to 8 feet above the water line. The remains of the Oliver Olson form the base of a newer extension of the south jetty into the Pacific; the hull, filled with more basalt and cement, can still be seen at low tide if you float too close to the jetty as you cross the Coquille bar. This bar is still a dangerous thing. Three well known natives of Bandon, friends of my parents, stalwarts of the community, highly familiar with the treachery of the Coquille, drowned in a capsized vessel as they came home across the bar several years back. There are some things that will always be constant.

The syrup of the river seems visually thick but it is actually a cold, cold water. The river runs high in the winter and spring and the surrounding fields and valleys upstream flood every year. I remember many days each year when schoolmates of mine were not at school because they were trapped in their houses in little dairy farms nested in those tiny valleys off of the river. You either had a boat to cross your farm pasture to get to the main road and hope that it was not also flooded, or you stayed home to sandbag the milk house and barn. The Coquille used to rise so fast that it wasn’t uncommon after a really bad spring rain to see bloated cow corpses floating out to sea past the docks of the marina.

When I was ten, my father took me upstream on the river just down from a little hamlet called Riverton. The word “hamlet” wasn’t exactly how I thought of it back then – I think my mother’s disparaging term was “wide spot in the road”. In those days, Riverton had a ferry crossing that would get you over to a rural road on the other side of the river to another place called Randolph. The old ferry would handle only a couple of cars if I recall. There were tow cables stretching across the river and an old diesel engine that manipulated the pulley and the ferry maneuvered back and forth between the banks solely on the judgment and grace of the old ferryman. The last time I went to Riverton, the ferry was not there and the road that dropped down to the landing was overgrown with grass. Not a trace to show a common way across. The old storefronts were there. But there was no visible evidence of a rural commerce once unfettered by modern technology and time.

If you are on the Coquille in the summer, and as long as you travel far enough upstream a mile or so from town or the 101 highway bridge, and away from the ocean wind, you can imagine yourself on a very miniature version of Huck Finn’s Mississippi. It is hot and buggy as the syrupy water slowly flows by banks covered in brush and alder, low scrub salal and pine trees. People two hundred years ago, numbering in the thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, walked on these low banks and high banks, gathered reeds and hunted deer, fished for the fresh water fish upstream and salmon downstream, ate salal berries for health and nutrition. The Miluks, with their own hamlets of timber and woven grasses, traded with other tribes, the Hanis, the Athabaskans, the Dine. They were massacred by miners and settlers, or relocated to the Suislaw reservation and were inevitably disenfranchised from all. The land carries a memory of these footsteps, I’m sure.

There are sacred spots on the Coquille, though no language known carries the original stories and memories anymore. The legends have been diluted by time and ignorance. A commercial glaze has been applied to appeal to tourists and gamblers. At Bullard’s Beach state park on the Coquille, near the 101 bridge, ancient bones in ancient graves were found in 1969. I remember this event, not very publicized due to the academic nature of the dig, as the first time I realized that what I was familiar with was not what had always been. I guess I got “history” then, as some get “religion”.

Due south of that dig a couple of months later, perhaps two or three football fields in length away from the Indian burial site, in some dark spot on the Coquille my father drowned, an early dark evening in October 1969. It was very stormy and windy that day and my father was upriver some from the marina securing log rafts to pilings just off the banks of the Coquille near the bridge. Near the 101 bridge and the marsh lands that are now a protected wildlife sanctuary. In those days, there were wooden billboards stuck down in the mud of the smelly marshlands advertising everything from local motels to Lucky Strikes.

That dark spot of the drowned river estuary called the Coquille, or “little shell”, based on what I remember of the tidal flow and the fresh water push, is where fresh and salt most often meet. His boat was a 28 foot diesel outboard and was never found, though the Coast Guard dragged the area for a few days in the attempt to determine what had happened.

I think of that boat a lot nowadays, when I haven’t for decades. There is something about the story that to me has no ending. It may be because the boat was never found; there was no real closure in the determination of how my father drowned. He was an excellent swimmer, had survived crabbing in the Aleutians in winter, fishing out of Dutch Harbor in the summer season, and working in the Todd Shipyards for many years from the mid 1930’s until the 1950’s. To drown on a stormy river, and not the result of a bar crossing accident, or the swamping of forty foot waves in the Gulf of Alaska – this stalls my mind. In my dreams I am the Wizard of Oz and I give the right gift to everyone, I make everything complete, I offer closure for the most pedestrian of foolish desires. Even mine. I dream I go back and drag the river and find the boat. I see the boat in that sediment, that muddy stew of time and tide. I don’t dream that it gives me answers, I dream that it puts the period at the end of the sentence that now ends with a question mark.

The wound of the question may heal; the scar left behind will always be there. There are some things that will always be.

I’ve always lived near water. In twenty-some moves in my life, in three different coastal states, I’ve always either seen water from where I live or I could walk to it. It haunts me and I have fallen in love with it and I cannot leave it behind. There are elements of both ephemera and immutability in the sediment of the Coquille and that is my dad’s true grave. The tide comes in and out and the river bottom ever changes.

|

There are some things that will always be constant. |

Again, a nod to Norman Maclean.

(All photos unless otherwise cited are permissable Use granted by the Oregon State Archives

Photos by Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives, Copyright 2002)

15 comments

Skip to comment form

beautiful. haunting.

This is a beautiful essay.

Your father’s death is a mystery, indeed.

I live far to the south of you – the Matagorda and Galveston Bays used to be rich sources for marine and avian life. John Charles Audubon wrote that, on Galveston Bay, one could walk from shore to shore on the backs of seabirds (I assume he was positing a very nearly weightless walker).

Matagorda Bay was host to whooping cranes, which almost went extinct when the were hunted for their feathers. Now, they are threatened by condo developments.

The fate of estuaries everywhere, and of mangrove swamps, is an issue of prime importance as the Greenland ice-cap’s melting threatens to raise sea-levels dramatically.

I think that, today, it is better to be old than to be young.

I wish that I could offer hope to future generations, but I cannot.

I’ve been sitting here for 10 minutes going…wtf can I possibly say. Damn.

Resonant, careful, very beautiful.

Author

in unexpected places.

In updating this essay (confession: this is a revised previously posted piece from over a year ago), I found a boat that someone has been missing.

Though not my father’s boat.

The Oliver Olson, which I mention above, possibly served in WWII as the USS Camanga. An excerpt from the site I came across details the Camanga’s wartime service:

Unofficial USS Camanga Website

The Camanga was decommissioned in San Francisco on December 10, 1946.

I have some sad mail to send. My father’s pictures of the Oliver Olson aground on the south jetty are buried in the last boxes of my mother’s possessions. It’s the same ship, modified for lumber.

When I was a child, I could see depth numbers on the hull embedded in the jetty.

The fog in your top picture is arresting, stunning.

or how many revisions you may have done–it’s exquisite. And for some of us, heartwrenching.

I grew up in a little river town in farthest southwestern Wisconsin, across from the Iowa bluffs at the confluence of the Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers, first recorded by the explorers Marquette and Joliet in the early 1600s. I know all this detail by heart because my dad was an avowed “river rat,” self-made historian, artist, part-time archeologist, and local museum curator. (And it wasn’t even his hometown–he grew up “inland” by about 50 miles–came to Prairie du Chien for an archeological dig, met my mom, and was in love with her and the place the rest of his life.)

Your essay has personal resonance for me because my childhood memories are of walking along the muddy shore with Dad, looking for Indian artifacts and various shells and such; going fishin’ in his small boat, trailing my hands thru water lilies while he pointed out various islands and slews. . .

I didn’t lose my dad young like you–I can’t imagine the pain of that–but we lost him not long after his retirement to the goddamned scourge of Alzheimer’s. While it wasn’t the same kind of mystery that surrounds your father’s death, it was another terrible kind of unknowing, and I never got to say good-bye to him.

I don’t believe in “closure.” Maybe if I ever find it, I will. Neither do I believe that “time heals all.” Once one experiences deep loss, there’s no getting over it. It becomes integrated inside you, and the best you can do is to find ways to keep alive in your heart and honor the person who has passed. If any of that is true for you, know that you have beautifully honored your father, and your mother. Night

because of YOU!

Thank you for another beautiful chapter. So much I’ve learned from you.

I don’t know what else to say.

{{{{exmearden}}}}

I would love to hold your book and move from one chapter to the next and back, again.

No comment on this particular essay, as I haven’t been able to digest even a small part of it – requires thoughtful and prolonged reading, savoring, musing….I need more of all of that.

Thank you SO MUCH for sharing your work here.

I love this beautiful series of essays. My husband lived in Prosper a ‘stop in the road’ on the Coquille. It is like Huck Finn, I loved walking the dusty roads in summer. Your writing is wonderful, I look forward to more. I am saving these as they are beyond just the place and time, as all art does.

I love this beautiful series of essays. My husband lived in Prosper a ‘stop in the road’ on the Coquille. It is like Huck Finn, I loved walking the dusty roads in summer. Your writing is wonderful, I look forward to more. I am saving these as they are beyond just the place and time, as all art does.

My husband used to buy and sell logs in Everett. Log rafts are stored in salt water to protect them from boring insects and worms (probably larvae). A little bit like canning tomatoes or green beans in salt.

There are still gyppo loggers. I have a patient who parks his log truck in my parking lot and abashed, appologizes for the grease on his hands and wood debris on his shirt, when he comes in for his appointment. I don’t care, as long as he doesn’t wear cork boots with nails protruding from the soles. He starts work at 3 am to try to get his 3 loads a day in. He has to drive further and further. It is a hard way to make a living.

During the 20’s, the Serven family lived in a logging camp on the South Fork of the Coquille River. Dad was born in Gaylord. Some old schoolmates of his remembered him riding a mule to school in Powers. I never knew much about the river. Thank you.

until I had read your essay again exme. Yours is a special kind of writing. Thank you.