Your resident historiorantologist has lately been puzzling over the matter of how it is that Alberto Gonzalez and the current rubber-gavel-wielding “Chief US Law Enforcement Official” have not been brought before the World Court to stand for their crimes. Clearly, it doesn’t take the piercing legal intellect of a Harriet Miers to recognize that torture goes against everything Americans believe in – our nation is, after all, a product of the Enlightenment, that 200-or-so-year period starting around 1650 in which thinking humans chose to recognize science, redefine the roles of government and the governed, and repudiate things like tyranny. Given this definition, of course, the aforementioned “legal” experts clearly are not Enlightened individuals, but closer examination of what actually went on before the bar back then shows that the Gitmo Gang would find themselves right at home dispensing “justice” in a court of that era.

So join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll look at criminal justice in the Age of Powdered Wigs – and may find that the current cadre of ethics-averse thugs running our penal/information extraction system would have been right at home in an Enlightenment court.

This Ain’t Your Buddha’s Enlightenment

It was an age of refinement and reason (or, in the bizarro wingnut world, a dark time of godlessness and superstition) whose thinkers bequeathed unto us everything from the Constitution to Beethoven’s 9th. Great advances were made in all the arts and sciences, including the political: without John Locke, there’s no Declaration of Independence; take away Voltaire, and important parts of both the First Amendment and the Declaration of Rights of Man & Citizen go out the window. Recognizing and celebrating their own brilliance, the philosophes even got away with an historical oddity: they named their own movement, and it stuck.

The Enlightenment saw the first stirrings of social justice movements, though the activism often consisted more of genteel debates in salons and almost-bloglike publications than it did in armed revolt. The latter, of course, did happen – both the American and French Revolutions were direct results of pesky, pernicious progressive thought – but on the whole, the process of implementing all those vaunted ideas of social justice came in fits and starts. There was no “ah-hah” moment when the world’s political leaders and judiciary officials became Enlightened; rather, society clawed its agonizingly slow way toward it one enlightened-despot’s-edict (or one individual judge’s ruling, or one broadside screed) at a time.

Letting the Logic Cat Out of the Bag

If you’re a totalitarian leader at the head of an autocratic society, it’s never a good idea to allow your subjects to think too much. Sadly (for the dictator and his cronies), avenues of knowledge such as logic often prove quite tempting for use in buttressing the policies and beliefs the leader wants to instill – think of the way Rush Limbaugh uses the phrase “intellectual honesty.” While this has advantages in terms of legitimizing stupidity by covering it with a veneer of reasonable-sounding words, chances are that the more terms like “logical course of action” or “compassionate conservatism” are repeated, the more likely it is that former Kool-Aid drinkers will leave the ranch and start actually thinking logically or compassionately.

A great example of this is Thomas Aquinas (1224-74), who began applying logic and rational means to explain the existence of God at a time when the number of literate people in Europe wouldn’t have filled a modern sports stadium. Aquinas was a significant departure from the Neoplatonic ideas of Augustine of Hippo, the 4th-century North African bishop whose deference to Plato led to centuries of argument by analogy: “there are bodies external to mine that behave as I behave and that appear to be nourished as mine is nourished; so, by analogy, I am justified in believing that these bodies have a similar mental life to mine” (ibid.). Enlightenment heavyweight Renee Descartes would later paint himself into a philosophical corner by following this line of reasoning, eventually concluding that there may well be an evil genius directing his every move, and thus proving pretty conclusively that he was a better mathematician than a philosopher.

A great example of this is Thomas Aquinas (1224-74), who began applying logic and rational means to explain the existence of God at a time when the number of literate people in Europe wouldn’t have filled a modern sports stadium. Aquinas was a significant departure from the Neoplatonic ideas of Augustine of Hippo, the 4th-century North African bishop whose deference to Plato led to centuries of argument by analogy: “there are bodies external to mine that behave as I behave and that appear to be nourished as mine is nourished; so, by analogy, I am justified in believing that these bodies have a similar mental life to mine” (ibid.). Enlightenment heavyweight Renee Descartes would later paint himself into a philosophical corner by following this line of reasoning, eventually concluding that there may well be an evil genius directing his every move, and thus proving pretty conclusively that he was a better mathematician than a philosopher.

Aquinas saw things differently from Augustine, and began using the careful logical arguments of Plato’s student Aristotle to justify his assertions regarding theoretical knowledge. Chief among these was that while unyielding faith in the existence of God

should be accepted on the basis of divine revelation alone…it is at least possible (and perhaps even desirable) in some circumstances to achieve genuine knowledge of them by means of the rigorous application of human reason. As embodied souls (hylomorphic composites), human beings naturally rely on sensory information for their knowledge of the world.

So it was that Aquinas made it fashionable (and later, requisite) to buttress theological arguments with logical ones, and over the course of the next few centuries, whole generations of Scholastic thinkers bandied about varying interpretations of the relationship between reason, existence, and the will of God. Perhaps they did waste some time arguing about how many angels could dance on the point of a needle (not, as commonly misconstrued, on the head of a pin), as noted by Isaac D’Israeli (1766-1848; father of Benjamin Disraeli):

However, a great part of these peculiar productions are loaded with the most trifling, irreverent, and even scandalous discussions. Even Aquinas could gravely debate, Whether Christ was not an Hermaphrodite? Whether there are excrements in Paradise? Whether the pious at the resurrection will rise with their bowels?

But on the whole, the scholastic thinkers pressed forward the boundaries of knowledge through the simple (?) means of asking “why?” By the late 1300s, a small group of artists and intellectuals in France and Italy arrived at the (reasoned) conclusion that mere mortal humans actually contained within themselves a spark of the divine. While this in and of itself was not an entirely new perspective, what set this Humanistic view apart was that its practitioners created an entirely new, highly influential movement based on the expression of human creativity – and which, much to the consternation of the Church, often took its cues from the Classical (read: pre-Christian) civilizations of Greece and Rome. In time, this increasingly-unsubtle deviation from Church teachings led to creative types taking a more rational, question-based approach to some of the more essential Church doctrines:

The return to favor of the pagan classics stimulated the philosophy of secularism, the appreciation of worldly pleasures, and above all intensified the assertion of personal independence and individual expression. Zeal for the classics was a result as well as a cause of the growing secular view of life. Expansion of trade, growth of prosperity and luxury, and widening social contacts generated interest in worldly pleasures, in spite of formal allegiance to ascetic Christian doctrine. Men thus affected — the humanists — welcomed classical writers who revealed similar social values and secular attitudes.

The History Guide: Lectures on Modern European Intellectual History

…which is why the Renaissance chapters in most textbooks begin with this:

and end with this:

“E pour si muove” — (“But it does move”) — Galileo Galilei, under his breath, after recanting his beliefs to avoid conviction and judgment by the Inquisition

Weird Historical Sidenote: Nowadays, of course, it’s an article of faith among some Christian conservatives that an evil band of Secular Humanists are at work in our society, using the godless commie public education system to turn innocent children against the Lord. They talk a lot about “worldviews” with regards to these secular humanists, and get quite bunged up about the perceived threat presented by an anti-Godly worldview taking root in public schools. Modern secular humanists (who are more secular than humanist) should not be confused with the Renaissance sort (who were, as their art reflects so beautifully, quite the opposite).

What grew out of the Renaissance was an amplified respect for reason and rationality, a secular approach to scientific understanding, the concepts of Deism and religious toleration, and a whole lot of other things that scare the hell out of people afflicted with an Ashcroftian worldview. It scared those types back then, too; even some of the greats sometimes come off sounding like an eloquent version of Antonin Scalia:

And thus it is that every man in the state of Nature has a power to kill a murderer, both to deter others from doing the like injury (which no reparation can compensate) by the example of the punishment that attends it from everybody, and also to secure men from the attempts of a criminal who, having renounced reason, the common rule and measure God hath given to mankind, hath, by the unjust violence and slaughter he hath committed upon one, declared war against all mankind, and therefore may be destroyed as a lion or a tiger, one of those wild savage beasts with whom men can have no society nor security. And upon this is grounded that great law of nature, “Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed.” And Cain was so fully convinced that every one had a right to destroy such a criminal, that, after the murder of his brother, he cries out, “Every one that findeth me shall slay me,” so plain was it writ in the hearts of all mankind.

— John Locke, Second Treatise on Government

It’s Only a Misdemeanor

Michelangelo was breaking new ground in stone, Raphael in paint, and da Vinci in everything, but it took a little while for political philosophers to catch up with the artists – it wasn’t until the mid-17th century that people started writing about redefining the role of the government with respect to the governed. Oh, sure, there had been some advances in representative democracy in the course of the previous half-millennium, but we have to remember that the Magna Carta, while a great wing-clipping of monarchical power, was not exactly a groundbreaker in the field of human rights. So it was that while men like Baron de Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued for separation of powers and for social contracts on a societal scale, at the local level – and specifically in the courtroom – Enlightenment thought arrived late and tended to be applied a little unevenly.

This is at the root of my assertion that John Ashcroft, Abu Gonzalez, and Rubber-Gavel Guy are, in fact, Enlightenment men – but only in the sense that courts of the early Enlightenment were nearly as sadism-friendly as the ones of the Inquisition and the Medieval Age which had preceded them. The Torture Trio would have felt right at home, for example, with the way the Old Bailey (London’s central criminal court) extracted this plea in 1716:

To all which Arraignments, White and Thurland refus’d to plead, but stood obstinately without speaking or holding up their Hands; upon Which the Court read the Law to them, by virtue of which their two Thumbs were tied together with Whipcord, and drawn by the whole Force of two Men, each above a Quarter of an Hour, which having no Effect upon their, contumacious Humour, Sentence was pass’d upon on them to be press’d to Death according to Law but when they saw Death so near and terrible they relax’d, and pleaded Not Guilty to each Indictment.

Judges and juries had considerable power under early Enlightenment courts, with access to an array of confession-yielding threats and death-dealing punishments that would make a Tribune of Guantanamo seethe with envy. For misdemeanors, penalties included fines, public whippings, some time in the pillory, imprisonment, and “sureties of good behavior,” which might be though of as a long-term bail bond and which were often assigned in combination with one of the other forms of punishment. As collateral against the commission of future offenses for the criminally guilty-seeming,

(d)efendants who were found not guilty were also sometimes given this sentence, if it was thought they had the potential to commit a crime in the future.

So there you have it: more proof that the Torture Trio has claim to Enlightenment. This might’ve been the era of life, liberty, and property, but just how protected any of those rights might be was up to whims of the courts and the relative malevolency of the government as a whole – just like in neocon-occupied America.

On the Critical Matter of Establishing a Different Judicial Code for the Benefit of the Wealthy

With increasing frequency as time wore on, those trying to talk their way out of the death penalty for more serious offenses availed themselves of a peculiar kind of get-out-jail-free card called benefit of clergy. A Medieval practice in which the Church was permitted legal authority to punish or set free its own (and most recently asserted in the Catholic Church’s reluctance to turn over pedophile priests to the secular arm of the law), benefit of clergy began to be claimed by persons not necessarily affiliated with any church, so in the interest of “fairness,” some courts started using what amounts to a literacy test – defendants claiming benefit of clergy were told to read selected passages of Psalm 51 to see if they really were as godly as they claimed. Of course, this had the added plus of segregating the criminal underclass from the criminal upper class, and allowed the courts to mete out different standards of justice based on social status – again, just like today!

If you’re struggling to remember your Catechism right now, allow me to refresh your memory. Psalm 51 is often called Prayer for Cleansing and Pardon, or, in this case, the “Neck Verse,” as it saved so many necks from being stretched:

1 Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

2 Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin.3 For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me.

4 Against you, you alone, have I sinned,

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you are justified in your sentence

and blameless when you pass judgment.

5 Indeed, I was born guilty,

a sinner when my mother conceived me.

***10 Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and put a new and right spirit within me.

11 Do not cast me away from your presence,

and do not take your holy spirit from me.

12 Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and sustain in me a willing spirit.13 Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you.

14 Deliver me from bloodshed, O God,

O God of my salvation,

and my tongue will sing aloud of your deliverance.***

In 1623, benefit of clergy was extended to women who had stolen less than 10 shillings worth of stuff; they got equal terms with men in 1691. By 1706, the reading test had been abolished, and the benefit granted in the case of all cases except those concerning offenses for which it was specifically excluded.

A defendant usually only got to use the benefit of clergy defense once, most often in the reduction of a death sentence. Persons so released were branded at the base of the thumb – “T” for theft, “F” for felon, or “M” for murder – to mark those who had availed themselves of the benefit, but even then, the tough-on-crime types didn’t think it was enough. From 1699 to 1707, “T” brands were inflicted on the cheek, but it didn’t exactly take an Attorney General of the caliber that John Edwards is going to be to realize that cheek-brands were making a whole class of people permanently unemployable, and thus drawn further into the criminal underground. With the brands relocated back to the thumb, the practice continued until the year of the ratification of the US Constitution – the last branding sentence at Old Bailey was handed down in 1789.

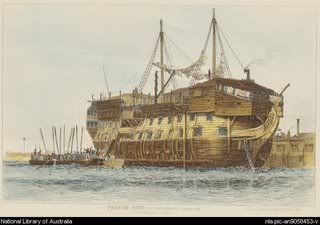

And May God Have Mercy on Your Soul

For the felonious – or those who were granted benefit of clergy by courts that felt the whipping/branding combo too lenient – things could get especially gruesome. Between 1706 and 1718, some judges construed benefit of clergy to allow the sentencing of up to two years at hard labor in a house of correction, or “Bridewell,” and after the Transportation Act of 1718, it became possible to simply ship the convicted off to the far ends of the Earth, there to serve as indentured servants (in America) or as penal colony settlers (Australia). In a sense, the practice of Extraordinary Rendition, so beloved by contemporary interrogators, had its start here.

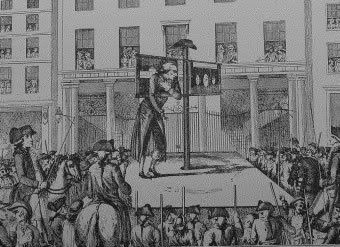

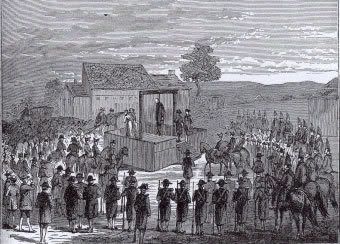

Many felony cases ended with a sentence of death, but there were several outs – in addition to the pillory (the use of which was discontinued in the early 1800s), military or naval service, pardons, and “respite of pregnancy” were used in commutation. For those not fortunate enough to gain a lesser sentence – or for those like Mssrs. Thurland and White above, who were proved circumstantially guilty and found in possession of evidence of their crimes – death came in any number of unpleasant ways, as noted in these selections from oldbaileyonline.org.uk. Hanging was the preferred method in the early days; most of the ones in London back then occurred at Tyburn. The procedure was one that let the condemned know who his buddies were:

The convict was placed in a horse drawn cart and blindfolded. The noose was then placed around his/her neck, and the cart pulled away. Until the introduction of a sharp drop in 1783, this resulted in a long and painful death by strangulation (friends of the convicts often helped put them out of their misery by pulling on their legs). Some of the most serious offenders were hanged near the place of their crime, as a lesson to the inhabitants of that area.

Hangings were public events even after they were moved to Newgate prison in 1783, but by 1868, concern over rioting and such led officials to move the executions to with the prison’s walls.

Strangling to death in a noose might’ve been bad, but it wasn’t the worst that judges with one foot in the world of science and another in Bible-inspired jurisprudence could come up with: until 1790, when the practice was abolished, women accused of treason were burned at the stake, often (though not always) after being strangled. When burning became illegal, women convicted of these crimes were hanged and quartered instead.

And oh, yes, it gets worse:

Judges occasionally ordered that the bodies of those convicted of egregious crimes and hanged should be hung in chains near the scene of their offence. This practice was supplemented by an act of 1752, “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder”, which dictated that the bodies of those found guilty of murder and hanged should either be delivered to the surgeons to be “dissected and anatomised” or hung in chains. By increasing the terror and the shame of the death penalty, these practices were meant to increase the deterrent effect of capital punishment. They were abolished in 1832 (dissection) and 1834 (hanging in chains).

…especially for the treasonous:

Men found guilty of treason were sentenced to be drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, hanged, cut down while still alive, and then disemboweled, castrated, beheaded and quartered. It was alleged that merciful executioners allowed men to die on the gallows before dismembering them. This punishment was rare during our period (1674-1913), but occasionally those convicted of coining and petty treason were sentenced to be drawn on a hurdle only, but not quartered.

(Hurdle – 4. Chiefly British A frame or sledge on which condemned persons were dragged to execution. TheFreeDictionary)

“…all you have to do to qualify for human rights is be human…” — tagline of the soon-to-be-reopened NION

Incredibly, there were some who objected to the idea of a court with the power to order people disemboweled – settle down, Rummy; you’ve managed to make it fashionable again – but they were, then as now, swimming against a “get tough on crime” tide. Probably the most influential of these philosophes, at least in terms of criminal justice, was Cesare Beccaria, an Italian thinker who expressed some profoundly un-DOJ points of view in his 1764 tract, Essay on Crimes and Punishments. In fairness, of course, anything that would be publicly praised by Catherine the Great and Maria-Theresa, while being quoted by Voltaire, Adams, and Jefferson, was from the git-go bound for the dumpster outside Rubber-Gavel Guy’s office (italic emphases the author’s; bold mine – u.m.):

Observe that by justice I understand nothing more than that bond which is necessary to keep the interest of individuals united, without which men would return to their original state of barbarity. All punishments which exceed the necessity of preserving this bond are in their nature unjust.

***

The torture of a criminal during the course of his trial is a cruelty consecrated by custom in most nations (including ours!). It is used with an intent either to make him confess his crime, or to explain some contradiction into which he had been led during his examination, or discover his accomplices, or for some kind of metaphysical and incomprehensible purgation of infamy, or, finally, in order to discover other crimes of which he is not accused, but of which he may be guilty.

No man can be judged a criminal until he be found guilty; nor can society take from him the public protection until it have been proved that he has violated the conditions on which it was granted. What right, then, but that of power, can authorise the punishment of a citizen so long as there remains any doubt of his guilt? This dilemma is frequent. Either he is guilty, or not guilty. If guilty, he should only suffer the punishment ordained by the laws, and torture becomes useless, as his confession is unnecessary. If he be not guilty, you torture the innocent; for, in the eye of the law, every man is innocent whose crime has not been proved.

Crimes are more effectually prevented by the certainty than the severity of punishment.

***

The punishment of death is pernicious to society, from the example of barbarity it affords. If the passions, or the necessity of war, have taught men to shed the blood of their fellow creatures, the laws, which are intended to moderate the ferocity of mankind, should not increase it by examples of barbarity, the more horrible as this punishment is usually attended with formal pageantry. Is it not absurd, that the laws, which detest and punish homicide, should, in order to prevent murder, publicly commit murder themselves?

It is better to prevent crimes than to punish them. This is the fundamental principle of good legislation, which is the art of conducting men to the maximum of happiness, and to the minimum of misery, if we may apply this mathematical expression to the good and evil of life….

Would you prevent crimes? Let the laws be clear and simple, let the entire force of the nation be united in their defence, let them be intended rather to favour every individual than any particular classes of men; let the laws be feared, and the laws only. The fear of the laws is salutary, but the fear of men is a fruitful and fatal source of crimes.

Becarria’s influence later made its way into several amendments of the Bill of Rights, where today they remain a quaint reminder of a silly era in which men wore makeup and wigs.

Given that several of the executions, beheadings, “transportations,” and other offenses to human dignity listed above occurred long after the publication of Becarria’s treatise (initially published anonymously, btw – Becarria only “came out” after he was certain his views on justice weren’t going to result in his death), it’s safe to say that though a great amount of lip service has been paid to his ideals, we haven’t quite achieved his vision after lo, these 250 years. For that, we have to thank men like John Ashcroft, Alberto Gonzalez, and John Mukasey – the vanguard of the mouthbreathers who have been working hard to stymie every halting lurch toward universal human rights since the days of the Enlightenment itself. Without them, the French might not have settled upon the guillotine as a humane half-step toward making executions cruelty-free, nor established early on that breaking a machine that belongs to somebody else should be a capital offense.

Historiorant:

This could go much further – indeed, I see the nucleus of at least one more historiorant in this Enlightened can of worms – but while the Luddites and the guillotine certainly need to be discussed, I think I might’ve spent too much time on Aquinas (any speculation as to when was the last time a member of the Torture Trio might’ve uttered that particular line?). This being the case, perhaps I should end this here – along with announcement that I should be returning to my regular bat-time on Sunday evenings starting next week. Sorry, btw, for the irregular postings over the past month or so; between the end of the school year and putting the finishing touches on the Crusades book, it’s been tough to get these done by my self-imposed deadline.

This could go much further – indeed, I see the nucleus of at least one more historiorant in this Enlightened can of worms – but while the Luddites and the guillotine certainly need to be discussed, I think I might’ve spent too much time on Aquinas (any speculation as to when was the last time a member of the Torture Trio might’ve uttered that particular line?). This being the case, perhaps I should end this here – along with announcement that I should be returning to my regular bat-time on Sunday evenings starting next week. Sorry, btw, for the irregular postings over the past month or so; between the end of the school year and putting the finishing touches on the Crusades book, it’s been tough to get these done by my self-imposed deadline.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

gets better and better, mr moonbat. you are writing the kind of stuff that got me purged from the history department, only better. when I grow up, I want to be like you….’though, not having occurred for 53 years, I kind of think growing up is fading from unlikely into impossible.

a

brought you sumpin….

and a hearty raise of the glass for the Cesare Beccaria reference.

I do have to take issue with your John Locke as Scalia analogy, though.

Locke in that passage is describing the State of Nature, the primary philosophical contribution of the true Scalia of that era – Thomas Hobbes.

For Hobbes, the State of Nature is a warlike, dog-eat-dog place where survival of the community is dependent on a strong, all controlling monarch whom God has chosen to rule and whose only check on the abuse of his power is the ever present threat of revolution.

A very Bushist outlook indeed.

Locke, on the other hand, is the Al Gore of his time, rejecting the monarchical divine right in favor of a more equal and democratic social contract, where people still come together for their own security, but do so as independent and reasoned beings.

Not hard to see how Locke’s version of the social contract would appeal to thirteen English colonies united for their own preservation and desperately trying to justify their revolt from a particularly Hobbsian monarch.

Now on to the floorshow:

I remember reading a description of public executions in France durring the revolution. I think it was in a collection of short works by Ken Kesey titled ‘Demon Box’ but I don’t know the original source.

When most think of the executions in France the Guillotine comes to mind, but apparently there were just too few of these contraptions to meet the demand for beheadings at the time and most executions were done by sword. The condemned would be held in position by two guards, one at each arm, and the executioner would swing the sword. Executions were also wildly popular events and drew huge crowds of spectators, including women and children, who would gather to watch a succession of public officials, bankers, landlords, and pesky neighbors brought to ‘justice’.

It seems that these enlightened revolutionaries were also not ones to pass up an opportunity presented by all the fesivities to make a franc or two, and gambling became a common part of the day’s events.

In one form, just as the sword was descending one of the guards, who likely had solicited a bribe beforehand, would tell the prisoner; “You’re free! Run!”, and the sporting members of the crowd, and staff, would bet on how many strides the prisoner would travel sans tete.

It was described as not uncommon for a particularly ‘lively’ victim to go ten or twelve strides.

The record (unofficially) was held by a woman who covered a full 25 strides before colliding with a parked wagon and falling to the ground.

As I say, I don’t have an original source for this and it may well just be a ‘tall tale’ or ‘urban legend’ of the time, but it does have a sort of ring of truthiness based on other things I’ve read of the times. It certainly stuck in my memory with all the rest of the junk.