Theodicy, or the problem of evil, can be stated in its classical form as a trilemma — a three-step dilemma.

(1) God is all-powerful.

(2) God is all-good.

(3) Evil exists in the world.

The combination of (1), (2), and (3) is internally contradictory. Logic demands that at least one of them be declared false. Yet, for most of the history of Western thought, all of (1), (2) and (3) were regarded as plainly true. Thus were philosophers and theologians – and pretty much anyone else who thought about it – exercised.

Nowadays, at least in some circles, there is no problem of evil, so formulated. “Enlightened” people may still wonder about the problem of evil in a watered-down form. They may ask, “Why is there evil in the world?” That is, they may wonder why (3) is true. To do so is still to engage, to wrestle with, theodicy, in some sense.

But since most people in the West nowadays have no inner qualms about denying (1) and/or (2), the trilemma is dissipated. The logical urgency, and the metaphysical crisis, generated by the conjunction of (1), (2), and (3) is gone.

I say that most people have no qualms about denying (1) and/or (2). One way to deny them both, obviously, is to deny that God exists at all. That takes care of both (1) and (2) in short order. But most people, going by polls, do not deny that God exists. Rather, I take it, most people have a more easy-going attitude to God than did their ancestors. “Is (1) really true?” Meh, who knows. “Is (2) really true?” Perhaps that one still raises some butterflies.

If we accept that God is all-good and deny that God is all-powerful – that is, if we work our way out of the trilemma by accepting (2) and (3) and denying (1) – we seem to left with a world in which there are spots of Godly absence; places where God isn’t, or where Her/His influence isn’t. Voids of divinity that pockmark the universe like holes in a Swiss Cheese.

From this standpoint it makes sense to say, or anyway it seems to make sense to say, that evil is an absence or lack. “Evil” names not something that one is but rather something that one isn’t. And indeed, it is sometimes said that Hitler was explicable by what he lacked; that the Khmer Rouge requires a negative, not a positive, avowal, to bring it within the fold of comprehensibility.

On the other hand, if we deny (3), we are either Pangloss from Voltaire’s Candide, or else we are “typical liberals.” Pangloss ran around Europe insisting all was for the best, even as he lost now an arm, now a leg, to the mindless idiocy of various wars and calamities. Pangloss, by the way, was Voltaire’s (1694 – 1778) way of making fun of Leibnitz (1646 – 1716), a philosopher who insisted that we lived in the best of all possible worlds. Well, that’s one way out of the trilemma.

We can also, if we are “typical liberals,” deny (3) by saying that all apparently evil acts are explicable by psychological malfunctions. We can appeal to Hitler’s childhood, or the effects of Pol Pot’s environment. Note that, if we do this, we are replacing, or trying to replace, a metaphysical question with an empirical question. It might be that we are changing the subject. Explaining why Ted Bundy committed evil acts isn’t, all by itself, to prove that the acts were not in fact evil. To think that is to carry in a lot of philosophical baggage unannounced and probably unnoticed as we dump it on the floor.

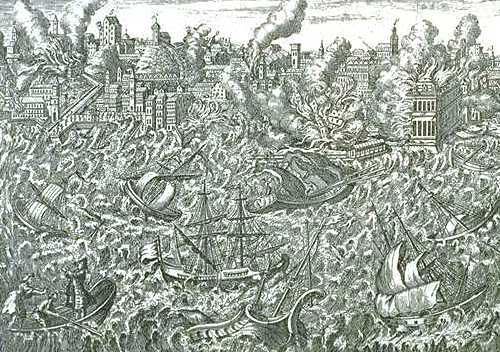

What sorts of things we count as evil, as instances or examples of (3), also depends on our metaphysical world-view. For a very long time, the 1755 earthquake at Lisbon was regarded as the apotheosis of evil in the modern world. Kant, Voltaire, Goethe, Rousseau struggled with its meaning.

(Indeed, one of the best recent books on the history of philosophy contends that we have been misinterpreting the history of modern philosophy. All those thinkers were struggling not so much with the staid and polite Problem of Knowledge, as we in America and England are typically taught, but with the terrifying and decidedly impolite Problem of Evil. To miss this, the author, Susan Neiman, convincingly contends, is to dismiss the motivation, the vexing and immediately felt ignorance in matters of mortal importance that brings us to philosophy in the first place.)

Nowadays, of course, Auschwitz is our apotheosis of evil. It is The Example by which we in the West remind ourselves that evil exists. It is what we struggle to understand. By contrast, we tend to regard anyone who views a mere earthquake as “evil” as merely quaint. We think this way because our world is less enchanted than it was, even a quick 200 years ago, and because evil has moved – by turns of culture too deep to explain in a blog post, even if I had the explanation – inward. It’s in our heads, in our intentions and thoughts, not in the world. Evil, we think, is in here, not out there.

I‘ve been musing on theodicy tonight because I notice that the New York Review of Books has an article about it. And here I have to take direct quarrel with the author, Tony Judt. Whatever we choose to do with theodicy, however we wrestle with it, however deeply or shallowly we feel the stress of the old trilemma or the new inward turn, we must not, must not, must not, write paragraphs like this:

My fourth concern bears on the risk we run when we invest all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem, however serious. The costs of this sort of tunnel vision are on tragic display today in Washington’s obsession with the evils of terrorism, its “Global War on Terror.” The question is not whether terrorism exists: of course it exists. Nor is it a question of whether terrorism and terrorists should be fought: of course they should be fought. The question is what other evils we shall neglect-or create-by focusing exclusively upon a single enemy and using it to justify a hundred lesser crimes of our own.

Our crimes, we understand, are “lesser.” By what standard we make this determination, I do not know. Not by body count, certainly. Not by the relative rationality of our bombings and torture chambers. And not because “they started it.” Even if that were true, and no less true claim has ever been made in the history of geo-politics, even if that were true it would have nothing to do with the problem of evil, or our participation in keeping it alive.

More to the point, the uses of “evil” in Bushy rhetoric (“evil-doers,” “axis of evil,” “forces of evil”) and in Washington rhetoric generally are not examples of “tunnel vision” at all. To think this is to think that the political (in the pejorative sense) rhetoric of evil is meant, in the first place, to refer to evil, and that the politicians who use it have missed something. But they have not. When Bush or Cheney or Reid or Schumer or Clinton or Obama speak of the “evil” we confront they are committing an evasion, a manipulation, and therefore an affront not just to metaphysics but to human decency. And they are doing it on purpose.

To think that we are “invest[ing] all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem, however serious” and that that problem is either “terrorism” or “evil” is not just to point out the problems inherent to the easy political use of the word “evil” but to participate in it. I have to assume that Judt is smarter than this; that he is writing for what he perceives to be an audience that can take looking in the mirror only in small doses. I doubt that his audience is really that squeamish (perhaps I’m an optimist). But the pretend idea that we can’t look in the mirror more rigorously is often the fake justification for a quiescent press. I’d rather not see an essay on theodicy, of all things, engage in it.

If there is one thing that I think we can say we have learned since World War II, or anyway since 2001, it is that Hannah Arendt’s memorable phrase “the banality of evil” is at best an incomplete description of the enormity we confront when we confront the problem of evil close to home. Arendt was referring to the calm lack of introspection or care on the part of the Nazis. Evil, when it comes, she was suggesting, does not come snarling and obvious. It comes with a lack of libido, in a suit, with a pen and a pile of forms.

Without comparing the Nazis to current America – to do that would be to miss the point I am trying to make entirely – I think we can say that we’ve learned that evil is not always without libido. Cheney and Bush, whatever else they are doing, are positively evincing joy at the wanton destruction of countries and constitutions and what Jefferson, following Locke, regarded as the natural rights of humans. Their followers are no less strident. There is no banality here. There is no absence of drive. There is lust and affirmation. In the non-pejorative sense of “political” there is political lust. Political affirmation. Of evil.

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas wrote:

[P]erhaps the most revolutionary fact of twentieth-century consciousness . . . is the destruction of all balance between explicit and implicit theodicy of Western thought.

Quoting this passage from Levinas , Neiman wrote:

An almost obsessive, sometimes questionable interest in cataloging twentieth-century horrors continues to fill the world with testimony in all forms modern media has as its disposal. But most agree that we lack the conceptual resources to do more than bear witness. Contemporary evil has left us helpless.

Speaking of Auschwitz, as Neiman was, she may be correct. But in other areas the problem is not lack of resources but lack of courage. If we let either Nazism or political expediency render us literally unable to articulate thoughts about evil, to render all of our theodicy implicit, to make it impossible to see evil in our own lands, and to conceptualize it and speak its name, then we will not have advanced, not have learned, not have earned anything.

If the word “evil” is good for anything at all, then it must be good for naming what we see before us when we see it before us. If theodicy is good for anything at all, it must be for helping us to understand why it is there, and how to conceptualize it and fit it into our understanding of our world and ourselves, lest it remain, unspoken but not uncommitted, in our own disenchanted future.