Capitalism causes cancer,

both the kind you’re thinking of,

and another kind:

cities.

Cities are tumors on the Earth,

our precious home planet.

Jul 21 2013

Capitalism causes cancer,

both the kind you’re thinking of,

and another kind:

cities.

Cities are tumors on the Earth,

our precious home planet.

Apr 29 2013

In fact there was no life at all.

Scientists now believe life began in a far more hellish environment than some kind of Frankenstein laboratory with lightning somehow creating life in primeval soup.

Most likely life was created by thermal vents deep in the lightless, airless recesses of the ocean. Cracks in the ocean floor opened to a hellish heat created by nuclear fusion that will continue until a dying sun engulfs the earth.

Today such vents are still alive with alien life that cannot survive the sun and oxygen-rich environment of the surface.

Anaerobic archaebacteria created that oxygen-rich environment from the poisonous methane that filled the atmosphere and then died from their handiwork.

Nitwits who call themselves environmentalists and pay no attention to science would return much of the stored methane to the surface and the atmosphere and call it clean energy.

They revere the distant sun, which will eventually destroy the earth, with its relative dribble of sometime energy and mostly ignore, or even denounce, the massive energy available from Mother Earth herself and her prodigious production of vegetation.

These fine folk even prefer to fill the land and waters and air with their own waste rather than recycling it for energy.

What kind of environmentalism would that be?

Best, Terry

Jul 08 2012

Elinor Ostrom, the only woman to ever win the Nobel Prize for Economics, died last month and we are all poorer because of it. She was a trailblazer in the field of economics, yet her findings have been largely ignored by politicians, policy makers, and the financial media. Few economists have ever even heard of her.

Why is that? Because her conclusions don’t help the cause of large corporations, governments, the wealthy and powerful.

She was Elinor Ostrom, a professor of political science at Indiana University, who devoted much of her career to combing the world looking for examples where people had developed ways of regulating their use of common resources without resort to either private property rights or government intervention.

In these days of environmental destruction and economic distress caused by rapacious corporations, we need people like Elinor Ostrom shining a light on alternative economic theories more than ever.

Sep 18 2010

The summer of 2002 was a drought year in the Klamath Basin.

An estimated 70,000 salmon died that year after the Bush administration “ignored its own federal biologists and divert more water from the Klamath River for farm irrigation”. According to documents, the decision was made because the farmers generally voted Republican. The Bush Administration then went on to order that water continue to be diverted for another eight years.

Only 24,000 fall chinook spawned naturally in the Klamath in 2004, followed by 27,000 last year.

The analysis from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service identified low water flows as a prime culprit in a major salmon kill on the Klamath River in 2002.

Because it takes several years for salmon to reach peak reproducing age, the effects of this huge fish-kill only started in 2005 when the National Marine Fisheries Service abbreviated the commercial salmon season. It cut the income of west coast fishermen “by 50 percent”.

California and Oregon indian tribes, that have depended on salmon fishing for thousands of years, also had their fishing quotas cut back by as much as half.

It’s easy to look at this example as an exception based on petty politics, but that would require you to overlook five centuries of political and economic policy.

Sep 16 2010

I met up with a good friend of mine this past weekend at a local dive bar. As the liquor loosened his tongue, he took a moment to complain about the wealthy elites he works for. Or as he put it, “those rich f*cks”.

My friend works for a non-profit, environmental group. The major contributors, all of the board of directors, and most of his coworkers are all wealthy. His new boss wants to focus on gifts for donations, such as tote bags that you can bring to the grocery store, rather than specific environmental causes.

This non-profit environmental group is a microcosm of what is wrong with the environmental movement today. Environmentalism is following down the same path to irrelevancy that labor unions traveled when they made the decision that 2% raises mattered and political movements didn’t.

Jun 28 2010

In the wake of the BP disaster, we’ve heard powerful stories from fishermen whose livelihoods may have been destroyed for decades or longer. However long it takes for the Gulf’s fish, oyster and shrimp harvests to recover, those who’ve made their livelihoods harvesting them will need to create a powerful common voice if they’re not going to continue to be made expendable. A powerful model comes from Seattle and Alaska salmon fisherman Pete Knutson, who has spent thirty-five years engaging his community to take environmental responsibility, creating unexpected alliances to broaden the impact of their voice, and in the process defeating massive corporate interests.

“You’d have a hard time spawning, too, if you had a bulldozer in your bedroom,” Pete reminds us, explaining the destruction of once-rich salmon spawning grounds by commercial development and timber industry clearcutting. Pete could have simply accepted this degradation as inevitable, focusing on getting a maximum share of dwindling fish populations. Instead, he’s gradually built an alliance between fishermen, environmentalists, and Native American tribes, persuading them to work collectively to demand that habitat be preserved and restored and to use the example of the salmon runs to highlight larger issues like global climate change.

The cooperation Pete created didn’t come easily: Washington’s fishermen were historically individualistic and politically mistrustful, more inclined, in Pete’s judgment, “to grumble or blame the Indians than to act.” But together, with their new allies, they gradually began to push for cleaner spawning streams, rigorous enforcement of the Endangered Species Act, and an increased flow of water over major regional dams to help boost salmon runs. They framed their arguments as a question of jobs, ones that could be sustained for the indefinite future. But large industrial interests, such as the aluminum companies, feared that these measures would raise their electricity costs or restrict their opportunities for development. So they bankrolled a statewide initiative to regulate fishing nets in a way that would eliminate small family fishing operations.

Jun 17 2010

I decided that under the current circumstances, providing some distraction would not be unwarranted…and I have a bit of an update to pass along.

Tonight will be another meeting of the West Orange Zoning Board…concerning the desire of Seton Hall Prep and the Archdiocese of Newark to turn McClellan Old-Growth Forest into sports fields and parking lots.

For those who haven’t been following, that is General-in-Chief of the Union Army George Brinton McClellan, who was fired by President Lincoln

If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time.

–Abraham Lincoln

…and subsequently ran against Lincoln for president as an anti-war Democrat in 1864. McClellan was also governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881.

May 03 2010

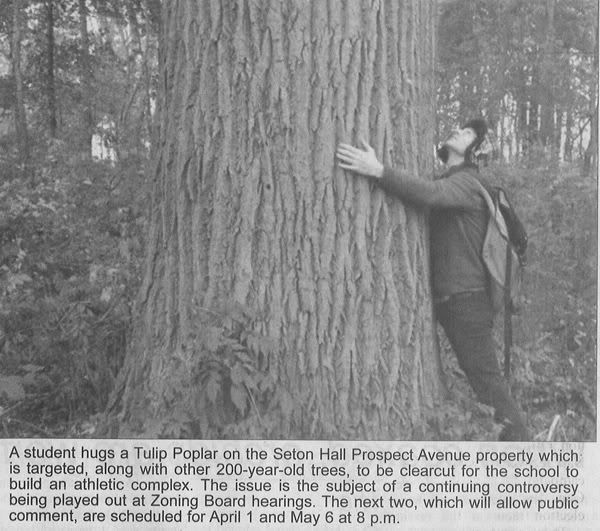

A student with one of the trees |

Never underestimate the power of a small but committed group of people to change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead

This is another update of a the original piece Save the Trees. The first update was DK Greenroots: Saving the trees…and maybe the bats.

Here in West Orange, NJ, past home of Thomas Alva Edison and present home of Whoopi Goldberg, a small but committed group of people is fighting the powers that be…in this case the West Orange Zoning Commission and Seton Hall Prep (and through it, the Archdiocese of Newark) in order to prevent the demolition of McClellan Old-Growth Forest in order to build sports fields.

I’m posting tonight in order to provide a conduit between those local voices and a larger community of activists. At least I hope so.

Feb 01 2010

Back in the middle of October I posted a piece entitled Save the Trees which you were all kind enough to elevate to the Rec List. It concerned the efforts of a local group to fight the powers that be in West Orange, NJ to prevent the destruction of the Governor George Brinton McClellan Estate Old-Growth Forest and Arboretum in order that Seton Hall Prep could build additional sports field and parking lots. This land is the only old-growth forest within the northern New Jersey metropolitan area which is unprotected and endangered.

Back in the middle of October I posted a piece entitled Save the Trees which you were all kind enough to elevate to the Rec List. It concerned the efforts of a local group to fight the powers that be in West Orange, NJ to prevent the destruction of the Governor George Brinton McClellan Estate Old-Growth Forest and Arboretum in order that Seton Hall Prep could build additional sports field and parking lots. This land is the only old-growth forest within the northern New Jersey metropolitan area which is unprotected and endangered.

You can read more of the background at the link above. Tonight, however, I wanted to provide an update on the situation.

The trees have won a temporary reprieve…as well as an endangered species of bat which may or may not be using some of them.

Dec 14 2009

Once upon a time, we saw progress, particularly technological and medical progress, as both miraculous and uniformly desired. The romanticized meta-narrative of the the Twentieth Century was that it was the age of startling innovation and that indeed humanity might find its salvation in the latest invention to improve the human condition. The most common utterance at the time to describe this phenomenon was what will they think of next? The airplane and the automobile revolutionized travel and with it the spread of information and population dispersal. Penicillin was considered a wonder drug upon its introduction and indeed many lives were saved when it began being used on a wholesale fashion to combat infectious disease. The first pesticides were considered miraculous because they greatly increased the yield of crops, with the hopes that their introduction would increase the food supply and in time make widespread hunger a thing of the past. It was believed that our own ingenuity would be our salvation and in time, there was no telling what long-standing problem would have a easy, understandable solution.

Later, however, we began to cast suspicion on any advance lauded in messianic or wildly optimistic terms. To our horror we discovered that the drug which took away morning sickness also created tragic, hideous birth defects in babies born to women who took it. Then we read that the pesticides that, though they meant to increase the food supply, actually created major problems in the ecosystem around them—problems that skewed the natural environmental balance quite unintentionally but quite undeniably. In attempting to eradicate one pest, we often caused a huge increase in population of another organism, creating a brand new problem in the process. The system of pest control as set up by Mother Nature then was seen as more desirable as the one shaped by human hands. And this idea began to take shape in the minds of many to the degree that this belief has many adherents in this age. Take a stroll down the aisles of your local Whole Foods if you need a visual demonstration.

But I will say this. Old ways of doing things are not necessarily better ways of doing things. Though we may have swung the pendulum from one side to another in the course of half a century or so, we shouldn’t lose sight of the true balance of things. Anyone who has walked down a street where automobiles are not available and where all traffic directed down a major thoroughfare is pulled by horses knows the filth and the stench that fills the air and collects on either side of the roadway. It is for that reason, among others, that the horseless carriage was developed in the first place. We must not ever assume that the motives of those who came before us were summarily evil or distasteful simply because they did not have the ability to measure what they did by the power of hindsight. Any of us could look like geniuses if we had that in our favor. We often look for an easy enemy when the true hard work is to work to reach the point where we recognize that there are no easy answers and no easy targets. Demystifying the past does not imply that we ought to summarily scrap its lessons. The mythology of past ages needs to be removed, but those who view past behaviors and past events without rosy gloss can find many helpful examples for contemplation, provided, one doesn’t heave it into the trash can in one go, assuming the whole bunch is rotten all the way through.

The larger point I am making is that it is tempting these days to assume that the advances of the past are purely evil, based on their unforeseen and unintended consequences wrought by best intentions. We have gotten to the point now that we are reluctant at times to modify the world around us even in the slightest, lest we upset the fragile balance of energy, life, and movement that defines existence as any being currently alive. While we are humans, we are also animals, too. Our will dictates the shape and pace of the world around us, of course, but so also does our very existence. Global Warming is the buzzword phrase of the moment and while I do believe that human decision making has modified the climate and weather patterns for the worst, I do also know that the environment has a way of being adaptive that we often do not grant it, nor fully understand. We see things through such selfish, human terms at times, and even our best intentions do not disguise the fact that everything often relates back to us in the end. We were created selfish. Self-preservation is what consumes us above any other preoccupation. Still, this is an impulse we must fight against if we ever wish to live in peace with each other. We have more in common than we admit, but it’s often the very things we don’t like to admit even to ourselves. There is a limit to our understanding, and in fifty years from now, perhaps we’ll set aside Global Warming for the latest theory that defines our guilt and gives us a rallying point that demands we be unselfish not towards each other, but towards all living creatures.

Whether we are kings and queens of the beasts is a matter for debate, but we do have the benefit of higher brain function, and this is what makes us so much more influential than the average mammal. We seem to confuse at times the fact that we are both animals and also beings beholden to reason, somehow simultaneously separate from the fray. We exist in our own orbit and while it is wise to understand that the earth does not strictly belong to us, we do modify it by our very presence. When a butterfly can create a ripple effect just by flapping its wings, imagine what the average person creates by stepping outside on his or her way to work on the morning. I’m not saying that we ought not be aware of our carbon footprint and we ought not recognize that being less wasteful and more protective of nature is worthwhile, but that one can micromanage one’s degree of social consciousness to an extent that ending up miserable is the inevitable byproduct.

In a broader context to that, I notice how we lament the slow progress of reform and regulation. Our split loyalties are often to blame for this as well. If we were able to reach a happy medium between the supreme authority of old ways and the supreme authority of new ways, then we might actually get something done in a timely fashion. So much of Liberalism and Progressivism these days is conducted from a defensive posture, with the belief in the back of the mind that no matter what is set in play, it will inevitably blow up in the end and create more problems. Well, with all due respect, this is merely part of being alive. Any decision made will create future problems that no one could ever predict at the outset, but this shouldn’t paralyze our needed efforts, either.

Again, reform is a constant process of refining, re-honing, and revision. It’s foolish to expect that one bill, one policy statement, or one innovative strategy will come out perfect and never need to be updated to reflect changing times. Rather than seeing this established fact as frustrating or limiting, we need to modify our expectations. As President Obama said last week in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, “…[W]e do not have to think that human nature is perfect for us to still believe that the human condition can be perfected. We do not have to live in an idealized world to still reach for those ideals that will make it a better place.” We are imperfect. Our ideas, no matter how immaculately crafted at the time, are imperfect, and the passage of time will render them more imperfect.

But there is a difference between expecting individual or communal perfection on a case-by-case basis and not striving to improve the lives of those around us. A century from now, if there is a blogosphere, I’m sure many people will laugh at the nonsensical barbarism of a previous age where every citizen of the Earth did not have health care coverage from cradle to grave. But in this hypothetical example, it would be easy for them to make this judgment if they made it based on a naive, cavalier understanding of our times. If they viewed them purely through the lens of their times without understanding the events, beliefs, and myriad of factors which led us to undertake the great struggle before us, then their own perspectives could not be taken seriously. Again, we might be wise to understand why we always seem to crave an enemy. Voltaire mentioned that if God didn’t exist, it would be necessary for humanity to invent Him. Likewise, if enemies didn’t exist, it would be necessary for us to invent them. That the very same people who speak of unity and can’t understand why we don’t have it are among the first to construct an antagonistic force and project all of their frustrations upon it is the deepest irony of all. Our most powerful enemy is us.

Jun 08 2009

It is with broken heart that I report the death of one of this nation’s most important and innovative environmental attorneys.

Luke Cole graduated with honors from Stanford, and cum laude from Harvard Law School. He could have done anything. He could have gone to work for any law firm in the country, and made a fortune. Instead, he moved to San Francisco and co-founded the non-profit Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment. As described on their website:

The Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment is an environmental justice litigation organization dedicated to helping grassroots groups across the United States attack head on the disproportionate burden of pollution borne by poor people and people of color. We provide organizing, technical and legal assistance to help community groups stop immediate environmental threats. In the 16 years that CRPE has been helping the poor and people of color resist toxic intrusions and protect their environmental health, among our many victories we have beaten toxic waste incinerators, forced oil refineries to use cleaner technology, beaten a 55,000-cow mega-dairy, stopped numerous tire burning proposals, helped bring safe drinking water to various rural communities, stopped a garbage dump on the Los Coyotes reservation in southern California, and empowered hundreds of local residents along the way.

His recent work included a groundbreaking case that is succinctly explained by his law school classmate, Ann Carlson:

Cole was well-known for his work on numerous leading environmental justice cases, including as counsel for the Native Village of Kivalina in its pathbreaking case seeking damages from large greenhouse gas emitters from the melting away of their Alaskan village.

If that sounds like he was tilting at windmills, you didn’t know Luke. He wouldn’t have pursued such a case if he hadn’t believed he could win it. His successful pioneering work, taking on the California dairy industry, made him the cover boy of the February, 2002 issue of California Law Magazine, in an article titled: Got Manure? How Environmental Lawyer Luke Cole Brought Dairy Construction in the San Joaquin Valley to a Standstill.

May 07 2009

This is a review of Noel Sturgeon’s (2009) Environmentalism in Popular Culture, an interesting book of feminist cultural criticism. Environmentalism in Popular Culture offers the most readily-accessible critique of an American mythology of the environment that I’ve read yet. Though it makes some rather quick connections between its identity politics categories and environmental analysis, it maintains the reader’s interest throughout.

(crossposted at Big Orange)